Naomi Clifford chanced on the subject of her book The Disappearance of Maria Glenn (published by Pen & Sword in April) while browsing the British Newspaper Archive. She blogs about aspects of Georgian life at www.naomiclifford.com and is currently researching the women executed in England and Wales between 1797 and 1837.

In 1829 a young man received an anonymous letter telling him that an heiress was willing to marry him if only he would only rescue her from a large house on the Clapham Road in south London, where she was being treated cruelly by her uncle. All he needed was a friend, a ladder and a gun.

It was a set-up. There was no heiress and the would-be bridegroom and his helper were promptly arrested. The target of the mischief-making was probably Mr Hedger, an unpopular and harsh magistrate who lived at the address. He also had received an anonymous letter.

I found this strange interlude when researching historical events near my home, but it set me thinking about the neglected subject of elopement. Soon I was avidly searching the Archive for stories of runaway marriages for a possible book. Of course, not all were straightforward tales of illicit love. Quite the opposite: many were alarming cases of coercion.

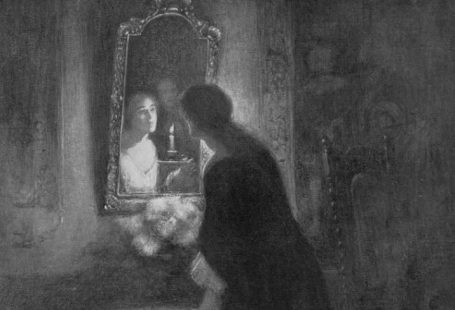

I settled on one major scandalous elopement, which had caused an almighty row, much of it played out in the press. One night in September 1817, 16-year-old Maria Glenn, said to be an heiress, left her home in Taunton in the company of the Bowditches, a local farming family. She later said she had been threatened with death and went with them only because she was terrified. On the contrary, said the young man who had bought a marriage licence in preparation for their wedding, it was all her idea.

The Taunton Courier was the first to print the story.

The words were probably written by James Scarlett, who was employed as a printer at the paper and just happened to be married to a member of the Bowditch family. The story was shot through with inaccuracies.

George Lowman Tuckett, a barrister, who was Maria’s uncle (and guardian) wrote a heart-felt objection.

The editor of the paper, John William Marriott, then decided to support Maria but later shifted his weight to the growing campaign against her. Like many others, he was having doubts about her version of events. Marriott was an old friend of (and related by marriage to) the Hunt brothers, Leigh and John, publishers of the radical weekly The Examiner, which also took the Bowditches’ side against Maria and her uncle.

After numerous court cases and a dramatic twist, Tuckett responded with two extraordinary pamphlets in his niece’s defence, each containing shocking allegations of conspiracy.

Was Maria telling the truth? For that, I turned to sources beyond the press, but it was the Archive that opened a window into a forgotten corner of history and guided me through the ups and downs of her amazing story.