This week’s episode of Who Do You Think You Are? took us down under and all over Australia. Craig Revel Horwood was able to learn how his ancestors on both sides of his family came to be in Australia and what activities occupied their days, from mining for gold to clog dancing.

Convicts in the family

Craig’s family history journey began with his sister’s retelling of their great-great grandfather Moses Horwood being convicted of theft and transported to Australia.

While it is of little surprise to learn that an Australian family can trace its Australian origins to a criminal ancestor, it is nonetheless exciting and shocking when you discover that your ancestor was a criminal.

As criminal cases were (and continue to be) an important news item, we were able to find an article detailing Moses Horwood’s criminal case and sentencing in the Sherborne Mercury, printed on 16 August 1841.

Moses Horwood and James Andrews were placed at the bar charged with the robbery in the Queen’s Hotel, Cheltenham, on the 12th July last. […] Mr. Samuel Griffiths, the proprietor of the Queen’s Hotel, stated that he was informed of the burglary about seven o’clock in the morning of the 12th July–that the prisoner Harwood [sic] has been a servant for some time in the house, and was well acquainted with every part of it–that he had quitted his employment about five months prior to the burglary.

The victim of this burglary was Sir Willoughby Cotton, and the stolen item in question was a despatch box, which contained ‘three orders–viz., the Grand Cross of the Bath, with Star and Badge, a Grand Cross of the Douranee Empire, and a Commander’s Order of the Guelph of Hanover, a gold stamp, with his name engraved thereon, two gold shirt pins, in a small case, a purse containing fifty sovereigns, a five pound note, and several other things’.

The account of the trial includes summaries of testimony given, including by one rather dedicated porter, Bentley Burrows.

Burrows, a porter in the hotel, sat up the whole of the night in question. Heard a noise of footsteps and a door open. Both sounds were in the direction of the front staircase, upon which Sir Willoughby’s room opened. He immediately took a candle and looked round the front hall. Heard some men whispering, and then footsteps across the grass. he called out, then jumped out of the back window and followed the persons. When within three or four years of the last man he escaped over the balustrade, which is about six feet high. (emphasis added)

Sherborne Mercury | 16 August 1841

In addition to a detailed account of witness statements and the evidence brought forward by the Crown, the article included the verdict and sentencing: ‘The jury, after a patient deliberation, returned a verdict of Guilty against both the prisoners. Mr. Justice Coltman, in passing sentence, commented upon the fact that Harwood [sic] had been in the employment of Mr. Griffiths, whose house he had afterwards robbed, and proceeded to state that he had thereby incurred a heavier weight of punishment than his companion in guilt. Harwood [sic] was then sentenced to fifteen years’ and Andrews ten years’ transportation’.

You can see in this one article that the last name of Moses is spelt differently throughout the piece – in the beginning, it is typed correctly as Horwood but switches to Harwood later on. Be sure to check and search for common misspellings and alternate spellings of family names.

See if your ancestor made any headlines

Transportation as a punishment was a controversial issue, particularly regarding those lawful individuals who emigrated to Australia, perhaps with the assistance, and at the behest, of the government to assist in growing the colonies there. From 1865, we read in the Ballymena Observer of a petition to permanently stop such convict transportation.

Gold rush in Victoria

Craig learned that the gold rush in Victoria played a large role in in his ancestor’s emigration to Australia and their subsequent fortune. Craig’s great-great-great grandfather Charles Tinworth, along with his wife Elizabeth, sailed from Southampton on 5 February 1854. Charles, just 20 years old at the time, was listed as an ‘Ag Lab’, or agricultural labourer, on his shipping documents, with a Mrs Smith listed as his intended employer in Australia. However, by the age of 26, we learn from his son Edward’s birth certificate that Charles is now a miner. Gold mining may have been the initial reason for the Tinworths wanting to emigrate to Australia.

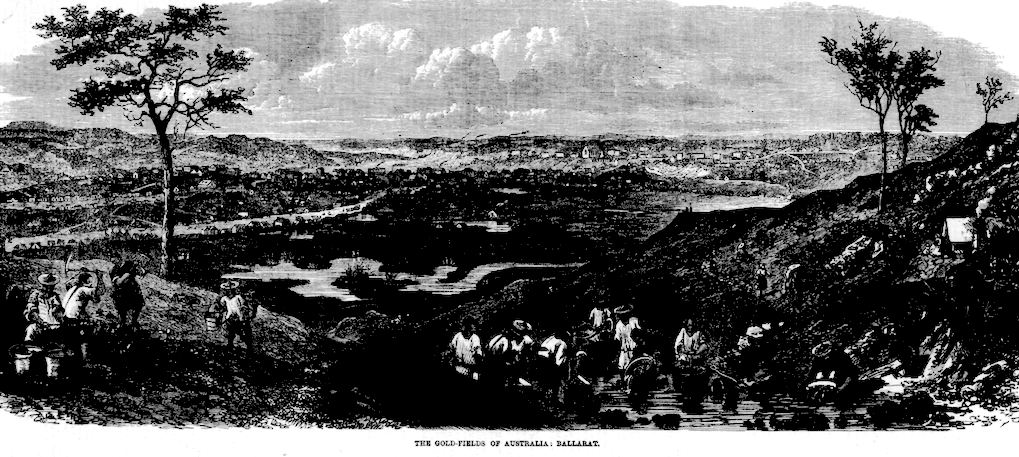

In search of gold, Charles and Elizabeth moved to Ballarat and lived, with their three children, in a tent city of some 40,000 people. Unsurprisingly, in such living conditions, sanitation was poor and the spread of disease rampant. Records indicate that Elizabeth suffered in health during this time.

The Illustrated London News and the Illustrated Times both printed detailed illustrations of the goldfields in Ballarat and elsewhere. Such drawings can provide you with valuable insight into the realities of living and working in the gold fields.

After paying a licence fee to the government, miners were entitled to only a 12-foot designated claim to search for gold. Despite facing early setbacks and failure, once Charles joined forces with his brothers James and Joseph, they were able to achieve success in deep mining. It was a more costly and dangerous operation, but it paid off for the Tinworths. In particular, Charles’ son Edward, at the age of 13, discovered a way to predict where quartz and gold could be found. Edward figured out that where quartz intersected with slate, there would be a lot of gold nuggets. Thus the Ballarat Indicator was discovered.

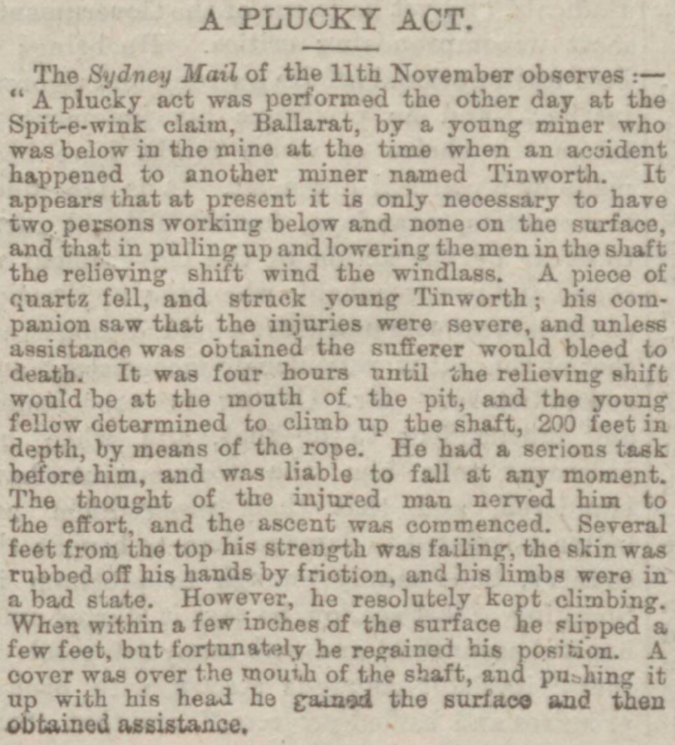

In search “tinworth” +”ballarat” with year range from 1880 to 1889, we found this article printed in the Manchester Courier and Lancashire General Advertiser on 13 January 1883. Perhaps a relative?

Cloggin’ away

It was with much joy that Craig learned he was not the only one in his family to enjoy a dance or performance. Craig’s great-great-grandfather Harry Macklin Shaw, like the Tinworths, came to Australia for work. However, Harry worked on a sheep station in New South Wales, as opposed to in the gold fields of Victoria. But Harry was more than just a labourer — he was a famed clog dancer, becoming the clog dancer champion of Australasia in 1871.

Clog dancing was incredibly popular in Australia in the late nineteenth century. On The Archive, we see that the highest concentration of articles returned for ‘“clog dancing” +Australia‘ come from the latter half of the nineteenth century.

While Harry’s printed challenge for a dance-off seems a bit odd to our modern sensibilities, clog dancing competitions for money were popular in the 1800s. As evidenced by Harry’s wager of £20 to the winner, a lot of money could be won from such competitions.

Discover more on clog dancing competitions

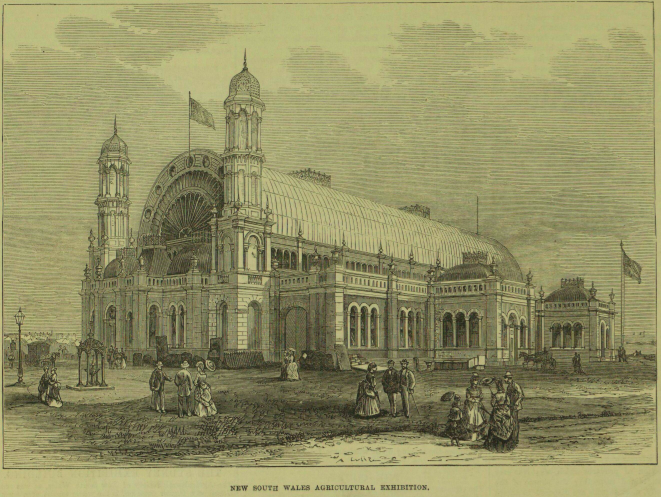

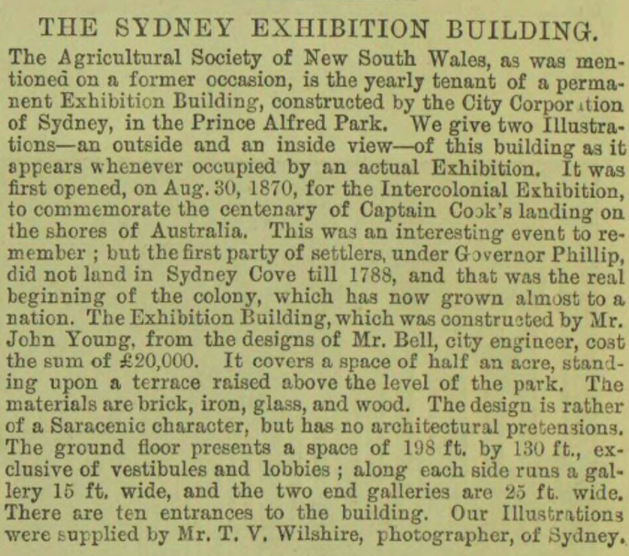

In the episode, they found these images of the Sydney Exhibition Building in the Illustrated London News, showing where Harry performed on Australia Day.

By navigating to the page preceding these beautiful illustrations, we discover a short article on the history of the building:

Search The British Newspaper Archive today to add more colour and context to your family history research!

1 comments On Crime and clogging in Craig Revel Horwood’s family

Many users have no idea what is sync,so friends now click here this site and read the all possible solution,so sync a mostly used search app in asian country,i am sure you can easy to use and search any site or read any artical.