As we continue to celebrate Black History Month at The Archive, in this special blog we will take a look at six pioneering Black British sporting heroes and their amazing stories.

Using pages taken from the British Newspaper Archive, we will take the opportunity to tell the inspiring stories of these Black British sportsmen, whilst attempting to understand the prejudice they faced and overcame in pursuing their different sports.

From left to right: J.E. London, Arthur Wharton, Len Johnson and Jack Leslie

We will look at the world’s first Black professional footballer Arthur Wharton (who was talented in many other sports), the first Black rugby player to play for England, James Peters, as well as Britain’s first Black Olympic medal winner, J.E. London. We will also look at trailblazing footballers Walter Tull (also one of Britain’s first Black army officers) and Jack Leslie, as well as boxer Len Johnson, who actively fought against the restrictions he faced due to his race.

So read on to discover more about these inspiring sportsmen, their achievements, and their enduring sporting legacies.

Register now and explore The Archive

Arthur Wharton (Football & Athletics) – 1865-1930

Arthur Wharton is widely considered to be the world’s first Black professional footballer – although he had intended to be a Methodist missionary. Born in Jamestown, Gold Coast (now known as Accra, Ghana) to a Grenadian missionary father and a mother who belonged to the Fante Ghanaian royalty, Wharton moved to England in 1882 to also train as a missionary.

But Wharton soon abandoned this calling in favour of a sporting career, and it was not a football one to begin with. The North Devon Gazette tells of how he ‘created such a great sensation in athletics circles by winning the hundred yards championship’ during the 1880s. Wharton’s race caused some comment in the newspapers of the time, the Athletic News labelling him ‘the dusky 100 yards champion.’

North Devon Gazette | 7 December 1897

But Wharton to some degree managed to overcome these prejudices as he carved out a successful career in athletics, and later on, in football. The same article in the North Devon Gazette, December 1897, describes how Arthur Wharton ‘is now a notable figure in the football world,’ despite only have a ‘purely superficial’ knowledge of the game some two years previously. Wharton played as a goalkeeper, and proved ‘a great success,’ with ‘his speed and wonderful nerve.’

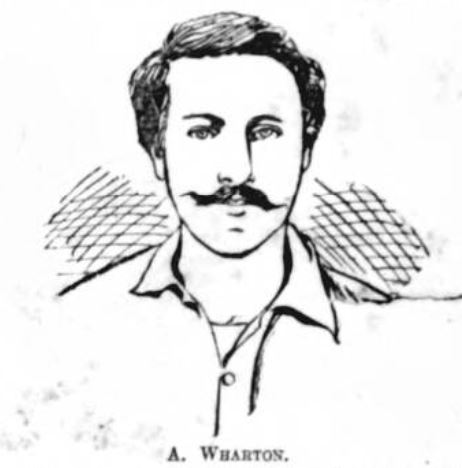

He soon turned professional, becoming the first Black British footballer to do so. Playing variously for Stalybridge, Rotherham, Darlington, Denaby and Sheffield United, Wharton continued to play right up and into his forties. The Star Green’un describes a triumph of Wharton’s later career in 1909, as he played for Commercial against Miners’ Tavern, ‘as even today can Arthur Wharton fill up a vacancy between the sticks:’

Miners’ Tavern were beaten by 2-0, but had it not been for Wharton’s excellent goalkeeping, they might easily have shared the points, or actually claimed them both. Hosts of calls were made upon Arthur, but to every one he responded with cleverness and confidence, and he is the only custodian who has, this season, prevented the Miners from scoring.

South Yorkshire Times and Mexborough & Swinton Times | 15 December 1906

There is little mention of Arthur Wharton until his death in December 1930. The Lancashire Evening Post reports how Arthur Wharton died aged 63 at Edlington, Doncaster, and remembers him as a ‘one-time English amateur champion sprinter, who, in 1886 established the record of ten seconds for 100 yards.’ It also remembers how he played for Preston North End, Rotherham and Stockport.

Meanwhile, the Sheffield Daily Telegraph remembers Wharton as a ‘goalkeeper of repute.’ Tragically, however, Wharton’s circumstances upon his death in 1930 meant he was buried in an unmarked pauper’s grave. Over sixty years later, a campaign by Football Unites, Racism Divides in 1997 saw a headstone erected for him, whilst in 2003 he was inducted into the English Football Hall of Fame.

Sheffield Daily Telegraph | 19 December 1930

Upon hearing of Arthur Wharton’s death, a man named John A. Barton wrote to the Sheffield Daily Telegraph with his memories of the pioneering goalkeeper. He remembers him for his popularity, and also for the way that he instructed the ignorance of those around him. Barton tells how Wharton had to correct some workman for referring to him as being the same race of the King of Persia, when ‘he was a native of West Africa.’ He was struck by his ‘tactfulness,’ and his ‘gentlemanly manner’ in responding to these men, and wanted to honour Wharton’s legacy accordingly.

James Peters (Rugby Union) – 1879-1954

James ‘Jimmy’ Peters was born in 1879 in Salford, Lancashire, to a Jamaican father and an English mother. He became the first Black rugby player to play rugby union for England in 1906, and shockingly was the only Black England player until 1988.

We find mention of James Peters in the Birmingham Daily Gazette in 1907, upon his marriage in Plymouth to Rosina Finch. He described as being ‘the famous Plymouth and international Rugby half-back,’ who would not be giving up his sport due to his marriage.

Birmingham Daily Gazette | 28 March 1907

Peters hit the headlines for a tragic reason later in 1910, after playing for Bristol, Plymouth, Devon and England. The Lake’s Falmouth Packet and Cornwall Advertiser reports how:

Footballers throughout the West of England will hear with deep regret that James Peters, Plymouth Rugby Club’s half-back, met with a serious accident, depriving him of three fingers on Wednesday morning.

Sporting Life | 9 February 1910

Sporting Life | 9 February 1910

Peters, working in Plymouth’s dockyards, had lost three fingers in a steam planing machine, and many anticipated that his trailblazing career would come to an end. The Lake’s Falmouth Packet and Cornwall Advertiser gives this tribute to Peters’s career:

Peters is widely known as an English international and a player for Devon County and the Plymouth Rugby Club. A half-back of great resource, and tactful to a degree, his services were of an invaluable character. No man has scored more consistently for Plymouth or attained greater popularity among officials, players, or the general public.

Indeed, Peters’s widespread popularity on and off the pitch was immense, Sporting Life reporting him to be a ‘most popular player,’ and the Birmingham Daily Gazette relaying how his ‘admirers have made him many valuable presents’ on the occasion of his marriage.

Peters managed to resume playing rugby, switching to rugby league in 1913 and returning to his native north west of England. He retired in 1914, and was remembered as a talented and popular sportsman.

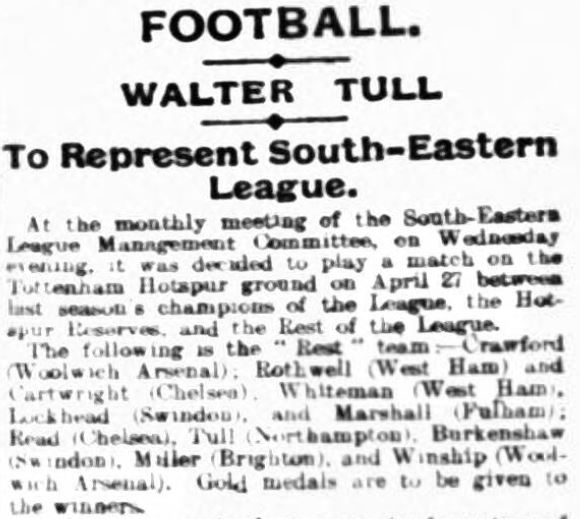

Walter Tull (Football) – 1888-1918

Of Afro-Caribbean descent, Walter Tull was born in Folkestone, Kent. His father Daniel was a carpenter from Barbados, Tull’s grandfather having been enslaved there. He became the third Black professional footballer (Willie Clarke being the second), starting his professional career with Tottenham Hotspur in 1909. After this signing, he toured South America, making him the first Black footballer to play in that continent.

Northampton Chronicle and Echo | 21 March 1921

In 1911 he moved to Northampton Town, but when war broke out in 1914, Tull became the first of the Northampton players to enlist in December of that year.

We get a glimpse of him in March 1918, in the Star Green’un, as he attended a Chelsea versus Tottenham Hostpur match at Stamford Bridge. He had by now attained the rank of second lieutenant, making him one of Britain’s earliest Black army officers. Tragically, Tull was killed in action later the same month in France, and his body was never recovered.

Some eight years later, Billy Lockett writes a stirring memorial for Tull in the pages of the Northampton Chronicle and Echo. Remembering Tull as being ‘strong as a lion,’ as well as for his ‘robust, perfectly fair, shoulder charges’ and his ‘long, low, shot,’ Lockett recalls the abuse that Tull faced as a Black football player. ‘Crowds yelled remarks at him unfit for print,’ but Tull, like Arthur Wharton, was a ‘gentleman,’ ‘a gallant fellow,’ and did not rise to such abuse.

With tragic foresight, Walter Tull anticipated his death aged only 29, as he ‘expressed an opinion to Northampton friends that he was returning to the front as an officer, but also to his death.’

And again, like Arthur Wharton, Walter Tull’s memory was honoured during the ongoing fight against racism during the late twentieth century. The Liverpool Echo reports on MP Bernie Grant’s visit to Northampton Town as part of the ‘kick racism out of football campaign,’ which also commemorated Walter Tull’s pioneering career as one of Britain’s earliest Black professional football players.

Jack Leslie (Football) – 1901-1988

Jack Leslie was born in Canning Town to a Jamaican father and an English mother. A prolific goal scorer, he had a long career with Plymouth Argyle. Whilst playing for Plymouth during the 1920s, he was the only Black professional footballer in the country at the time.

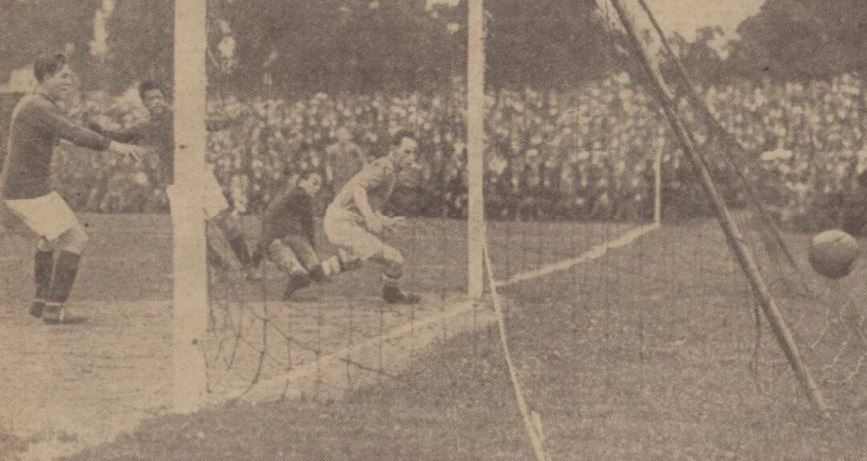

The Daily Mirror features a photograph of Leslie in 1925, as he scored ‘Plymouth Argyle’s first goal against Southend United, who were trounced 6-1.’

Jack Leslie scores against Southend United | Daily Mirror | 31 August 1925

It was also in 1925 that Jack Leslie received a call-up for the England national side, to play against Ireland. However, the invitation was withdrawn. It has been widely speculated that this decision was influenced by Leslie’s race, and so the first Black footballer to play for England was Viv Anderson, over fifty years later in 1978.

Despite this setback, Leslie’s career with Plymouth Argyle continued to flourish, and he became captain of the team. The Hull Daily Mail records how he ‘scored four goals against Nottingham Forest’ in October 1931, for which he was presented the match ball, and The People in November 1931 calls him ‘one of the greatest schemers in English football to-day.’

Daily Mirror | 31 December 1934

Having received a ‘serious eye injury‘ (Sheffield Independent) during a match against Bradford in 1933, Leslie eventually retired in 1935. He remains Plymouth Argyle’s fourth highest goal scorer.

After leaving Plymouth, Leslie became a boot-boy at West Ham United, having been offered the job by West Ham manager Ron Greenwood. During his time at West Ham, he cleaned the shoes of World Cup winners Bobby Moore, Geoff Hurst and Martin Peters – bittersweet for a man of such talents who could have, like them, played for his country but was disallowed due to his race.

J.E. London (Athletics) – 1905-1960

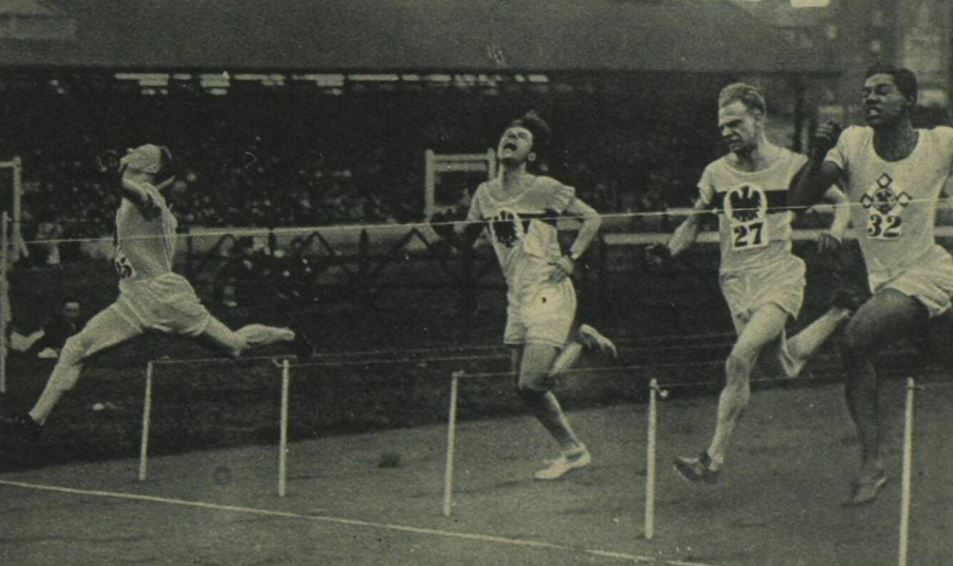

J.E. London, also known as Jack, was born in British Guiana (now Guyana) and moved to London as a child. There, he studied at Regent Street Polytechnic, and as he was a talented sprinter, he joined the Polytechnic Harriers. His impressive athletics career would lead him to the Amsterdam Olympics in 1928, where he won a silver and bronze medal, making him the first Black British Olympic medal winner.

In September 1926, London is described as being one of a ‘galaxy of brilliant athletes competing at the South London Harrier’s meeting at the Oval’ (Daily Mirror). However, newspapers of the time make a point of highlighting London’s race, something, it seems, the sprinter would not allowed to forget. At this particular athletics meet, however, London ‘recorded 10s in winning the 100 yards final.’

London’s appearance in Wigan in August 1927 was noted in the Athletics News, as he lined up against the champion sprinters of the North (W. Rangeley) and the Midlands (A.W. Green). Meanwhile, he set a new record in Dublin in 1928, as the Northern Whig reports:

J. London, of the Polytechnic and the Olympic sprinter, did ten seconds dead against the wind in winning the invitation 100 yards race.

After retiring from athletics, London became an entertainer, playing the piano at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane. He died suddenly in 1960.

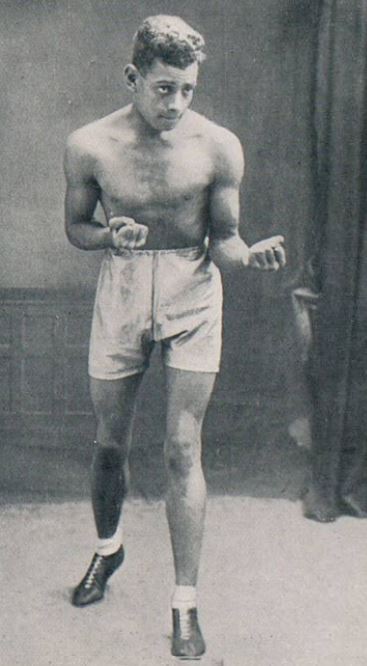

Len Johnson (Boxing) – 1902-1974

Len Johnson was born in Manchester. His father, Bill Johnson, was from Sierra Leone whilst his mother was Irish. Johnson quickly took to boxing, his father Bill managing him, and he soon proved his ability in that particular arena. However, due to the colour bar which existed in British boxing at the time, he was prevented from competing in championships in his home country.

Len Johnson | Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News | 18 February 1928

But that did not stop Len Johnson, as he had a long and successful professional boxing career. Moreover, Johnson was vocal in his criticism of the colour bar – his career was one of resistance as he became a civil rights campaigner, campaigning against racism at home and abroad.

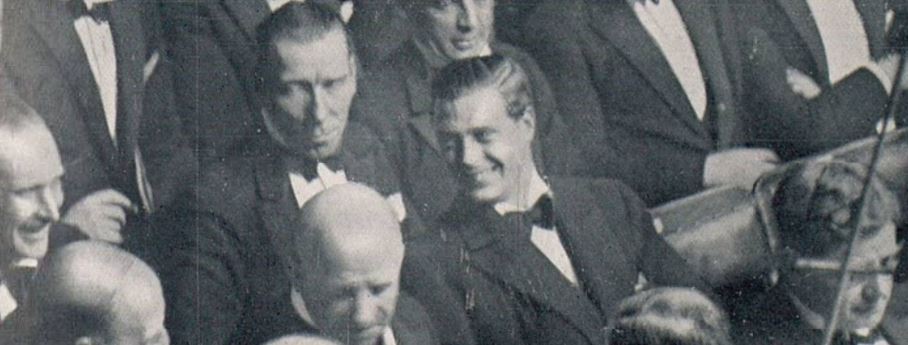

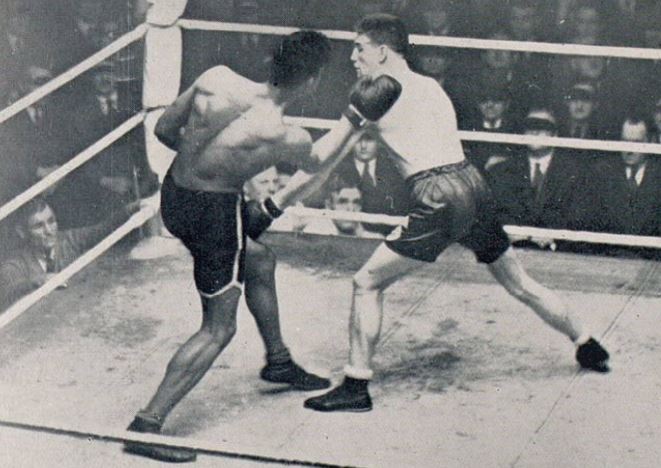

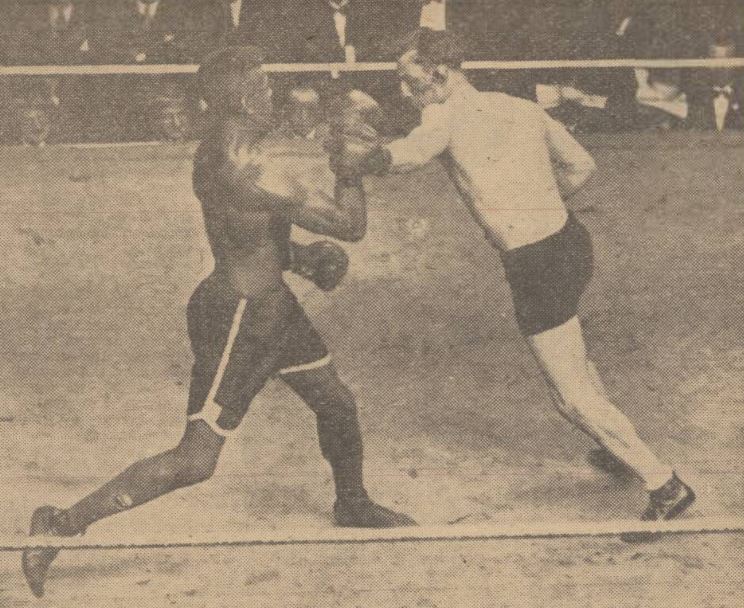

We find Len Johnson fighting in front of princes in 1928, as reported in the Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News. The Prince of Wales was in attendance at the Ring, Blackfriars, where Johnson took on Jack Hood in an ‘excellent contest,’ although Johnson was ultimately defeated on points.

The Prince of Wales watches Len Johnson | Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News | 18 February 1928

In 1929 the Western Mail describes Len Johnson as being ‘one of the cleverest middle-weight boxers in this country.’ In this particular bout, he defeated American ‘Sunny’ Jim Williams ‘by a wide margin of points.’

Len Johnson takes on Jack Hood | Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News | 18 February 1928

But by 1930, Johnson had had enough of the colour bar which banned him from competing in championship boxing in Britain. He was never allowed to forget his race, newspapers variously labelling him the ‘coloured boxer.’ And so, in August 1930 he stated his intention that he ‘was definitely not going to fight’ in his next match against Merlo Freciso, as reported in the Daily Herald:

Len Johnson, as already reported in the ‘Daily Herald,’ announced his intention of retiring from boxing because, he alleged, his colour had continually barred him from championship matches.

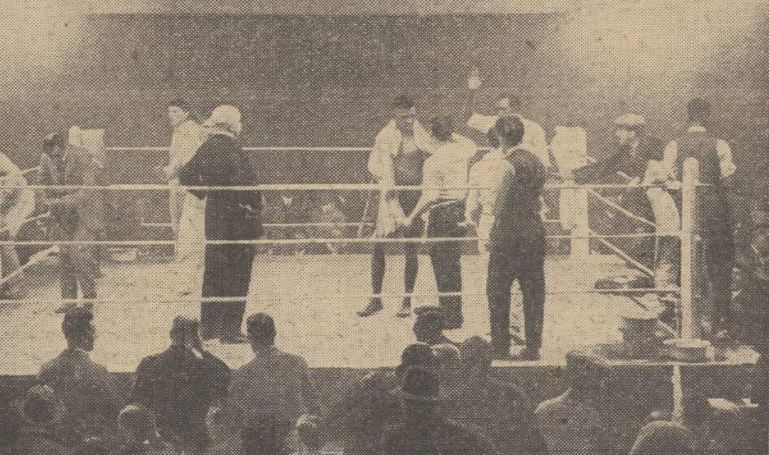

Johnson’s protest showed great courage, and the boxing colour bar was eventually scrapped in 1931. James Butler writing for the Daily Herald hopes that ‘some amends will be made to Len Johnson’ following the lifting of the barring clause, given that he ‘was the cleverest middle-weight in Great Britain.’

Daily Herald | 5 February 1931

But Johnson, quite understandably, had had enough of such institutionalized racism, and returned to where he had begun, boxing at fairgrounds. Hannen Swaffer for The People writes about his encounter with Johnson at a Newcastle fair, for although Johnson ‘is well circumstanced, [he] goes round the country with a boxing booth visiting fairs.’

With his two brothers and his wife, Johnson himself hardly took to the ring in this manner, but he did so to oblige the visiting Swaffer, showing his superiority to a ‘well-known local middleweight,’ demonstrating ‘the rapidity and skill of his punches.’

‘Len Johnson…smartly picking off a left swing by Ted Moore’ | Daily Mirror | 11 June 1927

This was not the end of Johnson’s career, however, as he is recorded by the Edinburgh Evening News in 1932 as boxing in front of ‘25,000 spectators in the vast Palais des Sports, Paris.’ But by 1939, Johnson lost interest in the sport, and during the war he was part of the Civil Defence Rescue Squad in Manchester.

But his activism did not stop there. He was a member of the Communist Party of Great Britain, a trade unionist, and community leader in his local Moss Side, where he campaigned tirelessly against racism.

Len Johnson is declared victor over Roland Todd | Sunday Pictorial | 27 September 1925

The legacy of these six Black British sporting pioneers is immense, as was their courage and bravery in overcoming prejudice in order to pursue their passions and talents. These are, however, just a few of the amazing and inspiring stories to be told, and to be found within the British Newspaper Archive. Moreover, it is of vital importance that we do not allow any of these stories to fade into history, rather, to tell and retell them as much as we possibly can.

Throughout the month of October we will be celebrating Black History Month at the British Newspaper Archive. Watch out for posts across our social media channels and more blogs celebrating Black historical figures. Our sister site Findmypast will also be celebrating Black History Month, showcasing useful resources for discovering Black history and genealogy.

Meanwhile, you can make a start researching Black history here on the British Newspaper Archive – what stories can you discover?