To celebrate the release of Netflix’s new film Rebecca, starring Armie Hammer, Lily James and Kristin Scott Thomas, in this special blog we will be looking at the publishing phenomenon that was, and still is, Daphne du Maurier’s Rebecca.

Published in August 1938, Rebecca was Daphne du Maurier’s fifth novel, the author having already had success with her 1936 work Jamaica Inn. The daughter of Sir Gerald du Maurier, a famous actor, and the granddaughter of George du Maurier, a cartoonist and novelist, Daphne du Maurier had an immensely creative background which was to bear fruit with the publication of Rebecca.

‘Study of an Author – Daphne du Maurier’ | The Bystander | 10 August 1938

An immediate publishing success; du Maurier went to on adapt her story for the stage and it was then picked up by Hollywood, directed by none other than Alfred Hitchcock in his first Hollywood film.

So read on to discover more about the initial critical reaction to Rebecca, how it was adapted for the stage, and how it was turned into an Oscar-winning film – using newspaper pages taken from the British Newspaper Archive, and don’t worry – if you haven’t read the book or seen the film, we won’t be including any spoilers!

Register now and explore The Archive

‘Perfect Specimen of a Best-Seller’

Released in the August of 1938, the first responses to Daphne du Maurier’s new novel were overwhelmingly positive ones. The Dundee Courier writes how Rebecca promises to be ‘the outstanding novel of the year,’ whilst the Leeds Mercury predicts it to be ‘one of the hits of the year.’ Meanwhile, H.S. Woodham writing for the Sheffield Independent was ‘held…breathless’ by the novel, impressed by du Maurier’s use of ‘fine, sensitive language.’

Dundee Courier | 10 August 1938

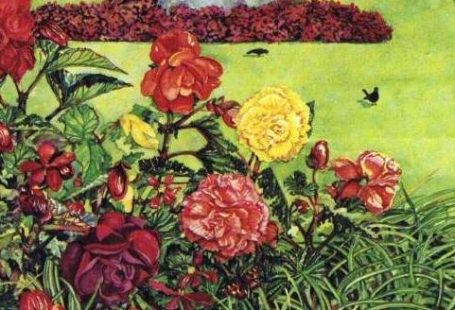

Indeed, many of the first reviews of Rebecca praise du Maurier’s use of prose. The Daily Herald revels in du Maurier’s departure from other contemporary writers’ ‘rough use’ of words, and praises her ‘high degree of story-telling craftsmanship:’

Miss du Maurier’s sensitive words flutter to her gentle service as birds, used to being fed with crumbs, gather in a garden when they hear breakfast being cleared away.

More praise is given to Rebecca in the pages of Britannia and Eve, which labels the novel ‘a most distinguished piece of writing…a strong story ideally told.’

Britannia and Eve | 1 October 1938

So what exactly were the winning ingredients of Rebecca, apart from the author’s use of language? The Tatler in September 1938 talks about the novel being ‘such a perfect specimen of a best-seller that it is almost like being shown round the factory by an expert.’

Certainly, atmosphere, character and plot all collide to create this best-selling effect, as is again noted in the Daily Herald:

In an atmosphere of scented doom, lush nature and leering fate which recalls the earthy romances of Mary Webb and Constance Holme, the unholy struggle is worked out with unexpected turns and continual suspense…The characterisation is done with brilliant deftness, and the authoress has a wonderful ability for catching a moment of time like a pinned butterfly and extorting from it all its beauty or its dread….All through the book you can identify yourself with the writer, and at the end everything is so vivid and so clear that you feel you have seen what she saw and can still hear the ominous conversations echoing in your brain.

Rebecca – A ‘Horrid Romance?’

But not everybody was so enchanted with this ‘second wife’s story‘ (Yorkshire Evening Post). The Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer describes Rebecca as a ‘novel of unreal characters and stage situations,’ likening it to the ‘horrid romances’ that were satirised by Jane Austen over one hundred years before. The Tatler also comments how it is ‘not a story of realism,’ whilst George Campbell writing for The Bystander remarks that du Maurier has a talent for ‘creating the stock characters of Romance, with a capital ‘R.”

Yorkshire Evening Post | 8 August 1938

Others, however, saw du Maurier’s return to such stock characters and stage situations as a modern reimagining of the classic novels of the Victorian era.

For example, W.L.A, writing for the Leeds Mercury, comments how:

Of Brontëan intensity, ‘Rebecca’ gives a romantic freshness to the ancient themes of tortured love in marriage and the ill-treated companion who marries a rich aristocrat and finds herself subtly despised.

W.L.A. goes on to note the familiar tropes included within du Maurier’s writing:

A great, mysterious house; a mysterious, sorrowing husband; a housekeeper like an evil spirit; everyone ruled from the tomb of an apparently drowned woman – it sounds perilously old-fashioned, but Miss du Maurier goes at it with such gusto, and with such mastery of atmosphere that nine readers out of ten will race through it and want to spread its fame.

Indeed, inevitable comparisons were drawn with the writing of the Brontë sisters, and most especially that of Charlotte Brontë, whose novel Jane Eyre bears striking similarities with Rebecca.

The Belfast Telegraph goes as far to herald this ‘triumphant return to the unsophistication fiction of Victorian romance, inspired and vitalised with such drama and vividness that might have emanated from Haworth Parsonage. Rebecca might almost have been written by the author of Jane Eyre.’

And because du Maurier was able to bring such themes, gothic atmosphere and intensity into the twentieth century, she emerges ‘out of the comparison not as a colourless copyist but as a modern rival.’

Rebecca on the Stage

Following the success of the publication of the novel version of Rebecca, Daphne du Maurier quickly went on to write the stage version. In April 1940 Rebecca opened at the Queen’s Theatre, and again promised to be as successful as its prose forebear.

Herbert Farjeon, writing for The Bystander, comments how du Maurier has achieved on the stage the ‘brooding atmosphere and strong drama’ of the novel, with Brief Encounter‘s Celia Johnson in the lead as the the second Mrs de Winter, playing the part with ‘a sensitive delicacy that is incapable of error.’

The Bystander writes in May of 1940 how Rebecca quickly established ‘itself as a play of the moment,’ with excellent acting and production contributing to its immediate success.

The play went through several runs across the country with different actresses taking the role of the second Mrs de Winter. Isolde Denham and Moyna McGill took the role when the play came to Nottingham in April 1941, which, according to Bernard Stevenson writing for the Nottingham Journal, caught the atmosphere of Mandarley to ‘perfection,’ with the novel’s air of ‘ever-present…menace and impending drama.’

But just as the actors were taking to the stage in Rebecca, across the Atlantic in Hollywood a film version was being created, with Laurence Olivier and Joan Fontaine in the lead roles. The Tatler in July 1940 features a photo spread of this remarkable event – of Rebecca being ‘simultaneously on stage and screen,’ which you can view here.

Rebecca the Record Breaker

By May 1940 the film version of Rebecca, directed by Alfred Hitchcock, was already seeing great success in the United States, as The Bystander relates:

The film ‘Rebecca’ has been greatly praised by the American critics, and has at New York’s Radio City Music Hall come only second to ‘Snow White’ in the length of its run. 750,000 people have seen it there.

Evening Despatch | 11 November 1940

Indeed, by July 1940 Rebecca had broken records, running for six weeks at the Radio City Music Hall – ‘a record for the house.’

And Rebecca was a landmark in film history for another reason – it marked Alfred Hitchcock’s American directional debut. The Bystander in June 1940 joyfully remarks how ‘Hitch…has done it again’ with his adaptation.

James Agate for The Tatler comments how the film is ‘admirably directed by Alfred Hitchock,’ whilst the Derby Daily Telegraph praises the director’s ‘brilliant job’ in adapting du Maurier’s novel. Hitchcock had decided to be truthful to his source material, telling the ‘story ‘straight” with none of the tricks of Hollywood.

Critics too were quick to praise the acting on display, and particularly the performance of Joan Fontaine. This was something of a breakout role for Fontaine, eclipsing the shadow of her sister Olivia de Havilland’s success as Melanie in the blockbuster Gone With the Wind, and she earned herself a nomination for an Academy Award for Best Actress.

James Agate for The Tatler gives this review of Joan Fontaine’s ‘enchanting performance’ as the second Mrs de Winter:

Let me say that Miss Joan Fontaine gives a truly exquisite performance of the child-wife, and I hereby announce the arrival of a young woman who can act of her own accord and volition, and is thus something different from the normal, made-up doll who weeps because her director pulled one kind of face at her, and laughs because the camera-man has pulled another.

Meanwhile, Laurence Olivier’s performance as Maxim de Winter was praised as ‘masterly’ by the Derby Daily Telegraph, with The Sketch praising his ‘romantic, moody, Brontëish de Winter.’

Elsewhere, however, the critics were not so kind, with The Bystander’s George Campbell fearing that Olivier might be ‘overdoing’ his ‘storms-and-wintry-sunshine manner,’ and James Agate noting how his ‘sulks and petulance’ might make him look like ‘the conductor of a jazz-band whose crooner has gone down with laryngitis.’

But Rebecca received the ultimate critical acclaim when the film was named Best Picture at the February 1941 Oscars, also winning the award for Best Cinematography. It had been nominated for eleven awards, the most of any film that year.

Hartlepool Northern Daily Mail | 28 February 1941

Netflix’s 2020 version of Rebecca follows in illustrious footsteps – tell us what you make of this retelling of Daphne du Maurier’s classic tale, or why not research your other favourite films and novels within the pages of the British Newspaper Archive?