On 15 July 1910 the Sheffield Evening Telegraph recorded the anniversaries of the day. One particular entry was this:

Prison hulks first seen on the Thames…1776

But what were the prison hulks, and what was life like on board these ‘floating hells,’ as they came to be known?

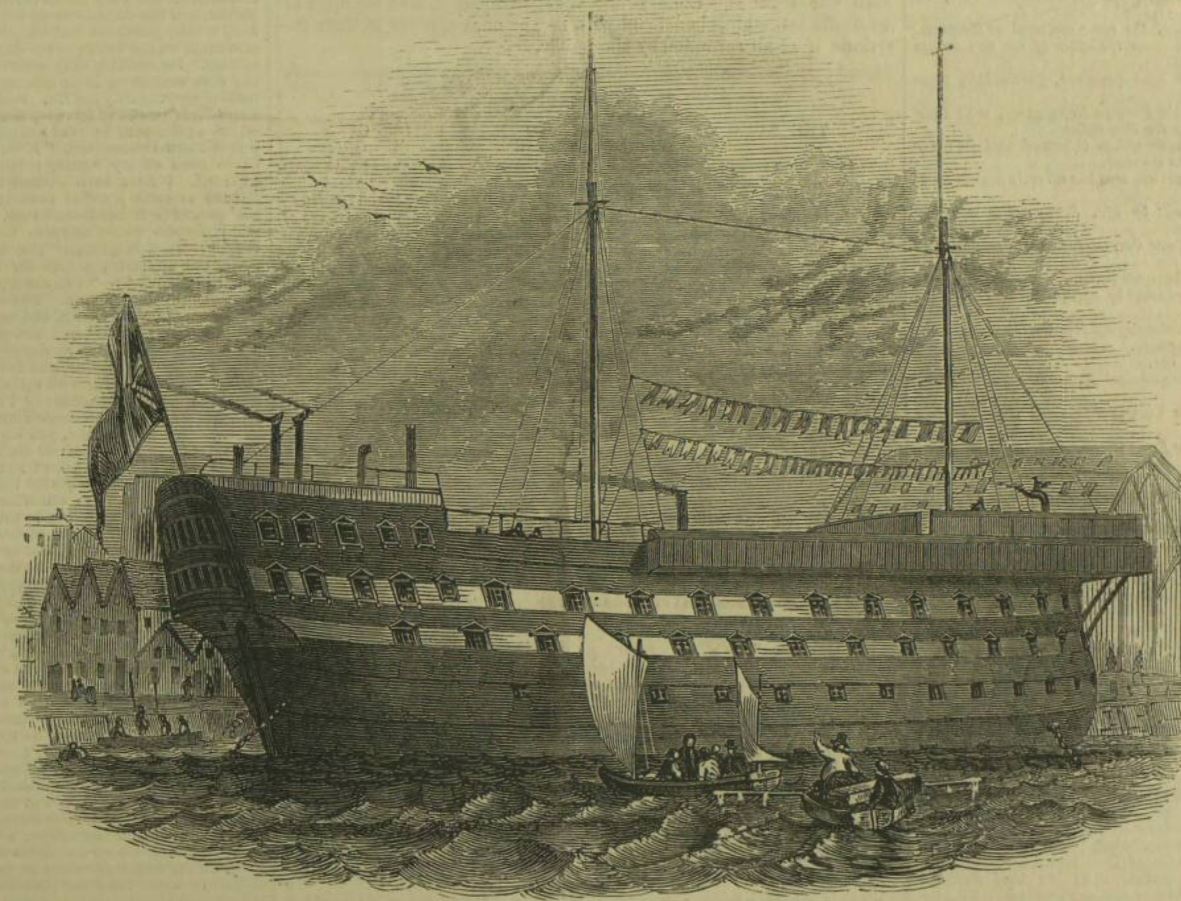

Prison hulk Warrior at Woolwich | Illustrated London News | 21 February 1846

As part of our history of law and crime month here on The Archive, we will take a look at what life was like on board the prison hulks of Britain and Australia, examining the conditions prisoners faced and how they were treated, all using pages from our newspaper Archive.

Want to learn more? Register now and explore The Archive

‘Freights of Human Vice and Misery’

As the Sheffield Evening Telegraph recalls, prison hulks were first seen on the Thames in 1776. But what did a prison hulk consist of? The Leeds Patriot and Yorkshire Advertiser, 5 January 1833, gives us the following description in an article entitled ‘Convicts on Board the Hulks at Woolwich:’

The hulks are large vessels without masts, which have been line of battle ships or frigates, fitted up for the reception of the convicts sentenced to be transported.

In charge of the prison hulk would be a captain, who was accompanied by a ‘certain number of inferior officers, with a chaplain and surgeon.’ Also onboard would typically be a hospital.

But even before the transportation of sentenced criminals to Australia began, prison hulks were in use to provide accommodation for Britain’s ever-expanding prison population. Transportation begun in 1787, and prison hulks were in use some time before this.

Here’s an excerpt from the Stamford Mercury, 8 January 1778, which demonstrates how prison hulks were in use to accommodate Britain’s prison population:

Most of the convicts at Newgate, under sentence of ballast heaving, were early this morning taken from that gaol, and put on board a lighter at Blackfriars-bridge, in order to be conveyed to the Justitia hulk, off Woolwich.

But with the advent of transportation, hulks became a method of housing prisoners before they were sent on the grueling voyage across the world to Britain’s new colony of New South Wales.

Botany Bay, New South Wales | Illustrated London News | 16 December 1865

Britannia and Eve, 1 August 1936, recalls the arrival of the so-called ‘First Fleet’ to Botany Bay, the first ship Supply arriving in January of 1788. The ‘First Fleet’ would become:

…the forerunners of a long succession of vessels which, for more than half a century, sailed regularly from Portsmouth, Sheerness, Cork, Dublin, and, of course, from London River with their freight of human vice and human misery. During that time, nearly a hundred and forty thousand men and women were transported to New South Wales, Van Dieman’s Land, Norfolk Island, and, finally, to the Swan River settlement in Western Australia.

But before this, many who were set to be transported spent time in prison hulks. We find examples of this in our newspapers, such as these reports from the Hereford Journal, from March 1787 and September 1790 respectively:

Yesterday 210 male convicts were taken from on board the hulks at Woolwich, and set out in wagons, under a proper guard, for Portsmouth, in order to be put on board the ships that are to carry them to Botany-Bay.

Thursday seven convicts under sentence of transportation from Cardiff, were lodged in our gaol, and yesterday morning they set off for Woolwich, in order to put on board the hulks.

Depiction of a transported convict | Illustrated London News | 8 February 1896

With the beginning of the Napoleonic wars, prison hulks were also to become home to prisoners of war. We found this curious excerpt from the Chester Courant, 23 October 1798, detailing one such prisoner:

A French prisoner on Monday died on board the Hero hulk, at Chatham. The agent, on inspecting his chests, discovered cash and notes to the amount of near 7,000l.

So this leads us on to ask, what exactly was life like onboard these hulks for prisoners awaiting transportation, prisoners of war, and those serving their sentences on the water instead of on land?

‘A College of Villainy’

We find a contemporary account of life onboard the prison hulks from the final speech of a condemned criminal named Williamson, who, according to the Derby Mercury, 13 October 1791, was ‘executed at Lancaster’ on 1 October 1791. His last words were a condemnation of the prison system, as he explains how ‘when a lad is sent to prison, it proves a school of wickedness to him. If he went half a rogue thither, he comes out a finished one.’

But he saves his harshest condemnation for the hulks:

But what shall I say of hulks! A college of villainy – from whence every man comes out a master of arts; having taken every possible degree of scoundrelism.

Williamson’s complaint is that the confinement of prisoners together is more likely to lead to more crime, for ‘if every felon [was] kept separate, prisons would then, and not till then, answer the true purpose.’ He believed that had he been punished in some other way, such as being ‘severely whipped,’ he would have gone ‘about his business’ and walked away from a life of crime.

So not only did hulks represent a potential breeding ground for further criminality, their cramped conditions meant they were also breeding grounds for disease. The Evening Mail, 17 December 1810, published a report by a French captain, Rousseau, to the French Minister of Marine, in which he details ‘the deplorable situation of the French prisoners in England, crowded in hulks, where they are deprived of all exercise:’

In the hulks, French prisoners breathed ‘fetid and corrupted air,’ which led to the inevitable contraction of ‘contagious diseases, which carries them off by the hundreds.’ This is corroborated by the memories of Jørgen Jørgensen, a Danish adventurer who was captured by the British in 1808 and taken prisoner. In the course of his career, Jørgensen had declared himself king of Iceland. He was eventually transported to Tasmania.

Jørgensen, as reports Britannia and Eve, describes Britain’s prison hulks as ‘sinks of misery and iniquity.’ He echoes Williamson’s sentiments of the hulks’ potential to cause more crime, rather than preventing it. Jørgensen describes the hulk Justitia and its fellow vessels as:

…‘schools of abominable pollution’ and ‘nurseries of deep crime,’ adding that ‘those who have been discharged from them have overrun England and spread vice and immorality everywhere in their track.’

He goes on to narrate the cruelty of the men in charge of the hulks, and the impossibility of complaint ever being made against them:

I have seen a captain knock a poor fellow down with one blow merely for not getting quickly out of his way when passing forward on the deck….Woe betide him, who should dare to open his lips except to say that the treatment on board was humane and kind.

French painter, Ambroise Louis Garneray, echoes Jørgensen’s testimony. Garneray was an official marine painter for the French navy, and The Sphere in November 1934, in article by Cecil King entitled ‘The Wooden Walls of Old England,‘ tells of how he was captured in 1806.

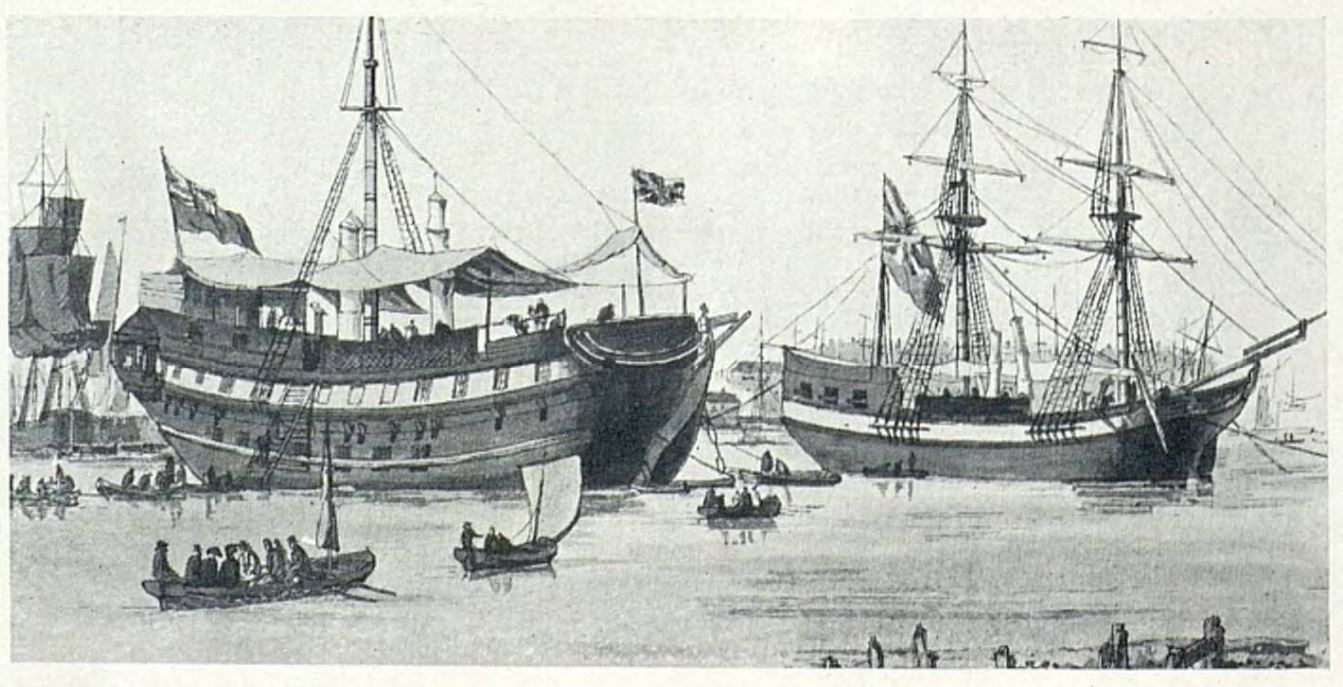

Hulks moored off the Tower of London in 1805 | The Sphere | 21 November 1934

Garneray went on to give ‘a lurid description of life on board’ the hulk Protée, comparing the hulk to ‘an immense sarcophagus.’ He describes how the prisoners ‘wore a suit of yellow material, stamped with the T.O. of the Transport Office,’ and how:

The prisoners were herded together amidships and spent their time in gambling, often with tragic results, or in making bone-ship models…

Perhaps gambling was where the wealthy prisoner in 1798 gained his funds? But by 1824, with the Napoleonic wars long over, the prisoners of war freed, the Morning Post details how:

The reports usually made respecting the state of the convicts in the prison hulks were presented by the proper officer, and read to the judges. It appeared that discipline and good-order had not been interrupted.

Convicts on Board the Hulks at Woolwich

However, the Leeds Patriot and Yorkshire Advertiser in 1833 is reporting how ‘several symptoms of insubordination have lately taken place’ upon the hulks stationed at Woolwich. It uses the example of one McGuinnis, a young lad who ‘was lately removed from Newgate, where his behaviour was of a bad description, and he began to play his pranks at Woolwich.’

Showing the severity of the punishment on the hulks, McGuinnis was then:

…brought up, and in the presence of several hundreds of his companions received a good flogging, which we understand has had a salutary effect, and he has ever since been docile and tractable.

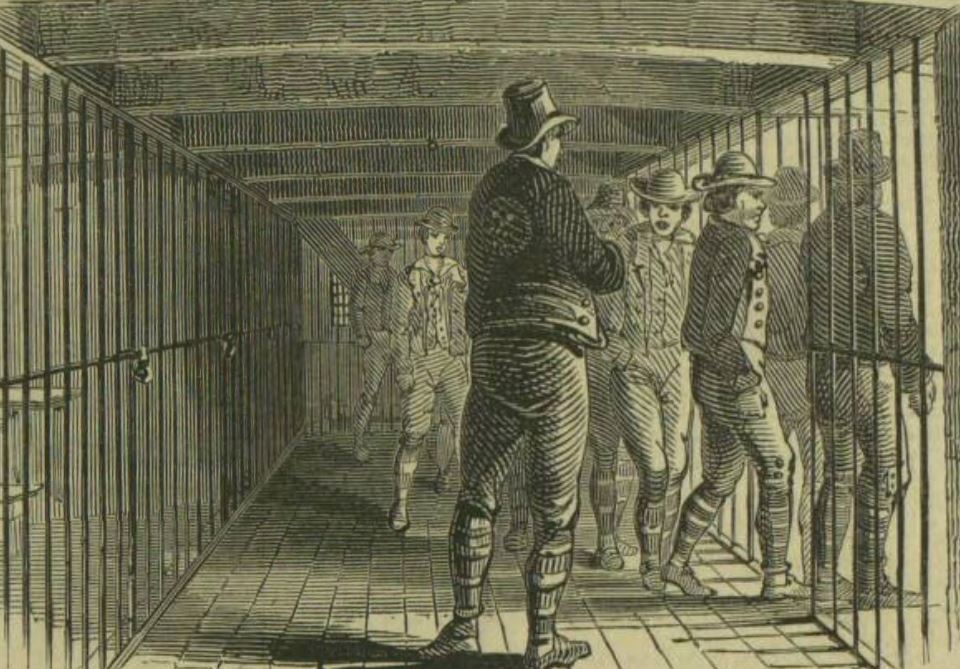

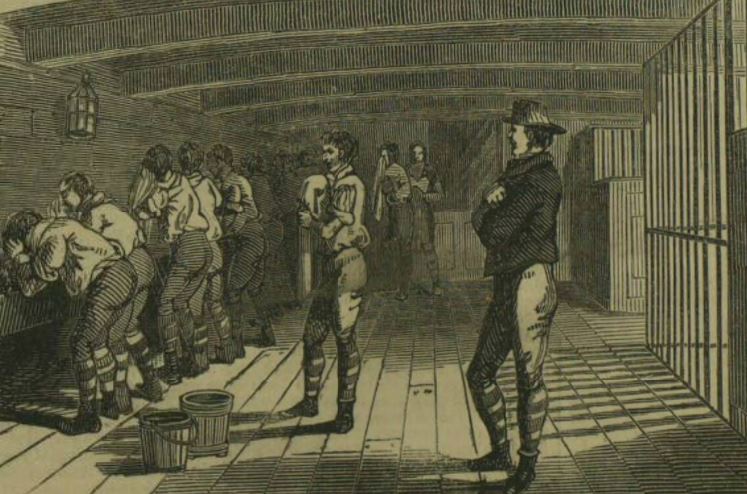

The gallery of a prison hulk | Illustrated London News | 21 February 1846

Another instance of so-called ‘insubordination’ was reported by the Leeds Patriot, as prisoners found ingenious ways to smuggle money aboard the hulks. The newspaper fears that the money would be used ‘to carry into effect some unlawful object,’ whilst including a letter from one these ‘adroit rogues:’

My dear, I am very short of every thing; I want particularly money, some of which I hope you will send me. Send me down some writing paper and a stone bottle of ink. In order that the money may come safe (i.e. free from observation) empty out the ink, and then put as many sixpences as you can spare in the empty bottle; when you have done this, pour on some melted pitch, which will fix the money at the bottom, and then you may pour in the ink again.

For all the Leeds Patriot’s scaremongering about the ingenuity and insubordination of prisoners onboard the hulks, it does give a fascinating contemporary account of what life was actually like for those imprisoned on the water. For example, the newspaper describes what a newly-arrived hulk prisoner might face:

On their arrival the convicts are immediately stripped and washed, clothed in coarse grey jackets, and breeches, and two irons placed on one of their legs, to which degradation every one must submit, whatever may have been his previous rank and station in the world.

The ‘washing-room’ on board a hulk | Illustrated London News | 21 February 1846

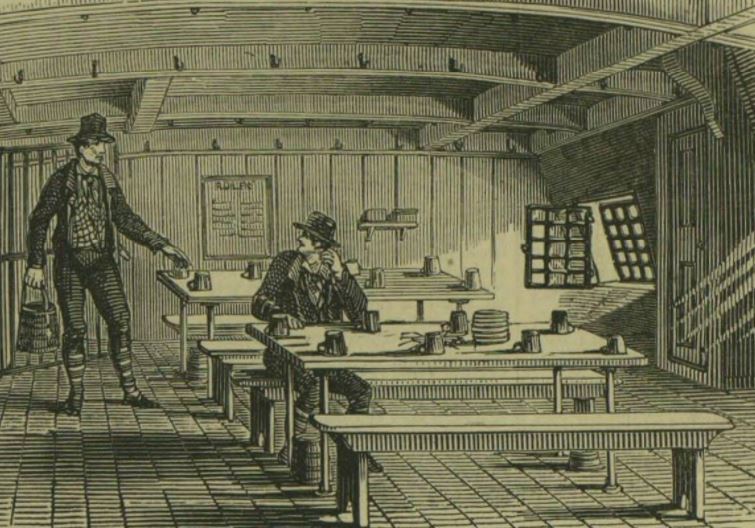

Meanwhile, ‘strictest discipline is maintained on board the hulks,’ with ‘extreme cleanliness enforced.’ Rations onboard the hulks were as follows:

The diet daily is 1 ½ lb of bread, a quart of thick gruel, morning and evening, on four days of the week a piece of meat weighing 14 ounces before it is cooked, and on the other three days, in lieu of meat, a quarter pound of cheese, also an allowance of small beer; and on certain occasions, when work peculiarly fatiguing and laborious is required, a portion of strong beer is served out to those engaged in it.

Prisoners onboard the hulks were often put to work, the hulks being ‘securely moored near a dock-yard or arsenal, so that the labour of the convicts may be applied to the public service.’ For every shilling earned, the prisoner would be entitled to one penny – however, funds were saved on the behalf of a prisoner, so that when they were freed after six or seven years, they would be ‘put in possession of £10 or £15,’ approximately £670 or £1,000 today.

Onboard a prison hulk | Illustrated London News | 21 February 1846

There were also, if the Leeds Patriot is to be believed, opportunities for betterment onboard the hulks. ‘Orderly conduct’ might result in having your irons lightened, or ‘being promoted to little appointments,’ relieving a prisoner from ‘severer labour.’ Indeed, onboard the Bellorophon at Sheerness, which housed boys younger than sixteen, trades were taught like bookbinding and shoemaking.

However, those beyond apparent reformation were often sentenced to transportation. And even when transported, such convicts could still be subject to the cruelty of the prison hulks.

‘Floating Hells’

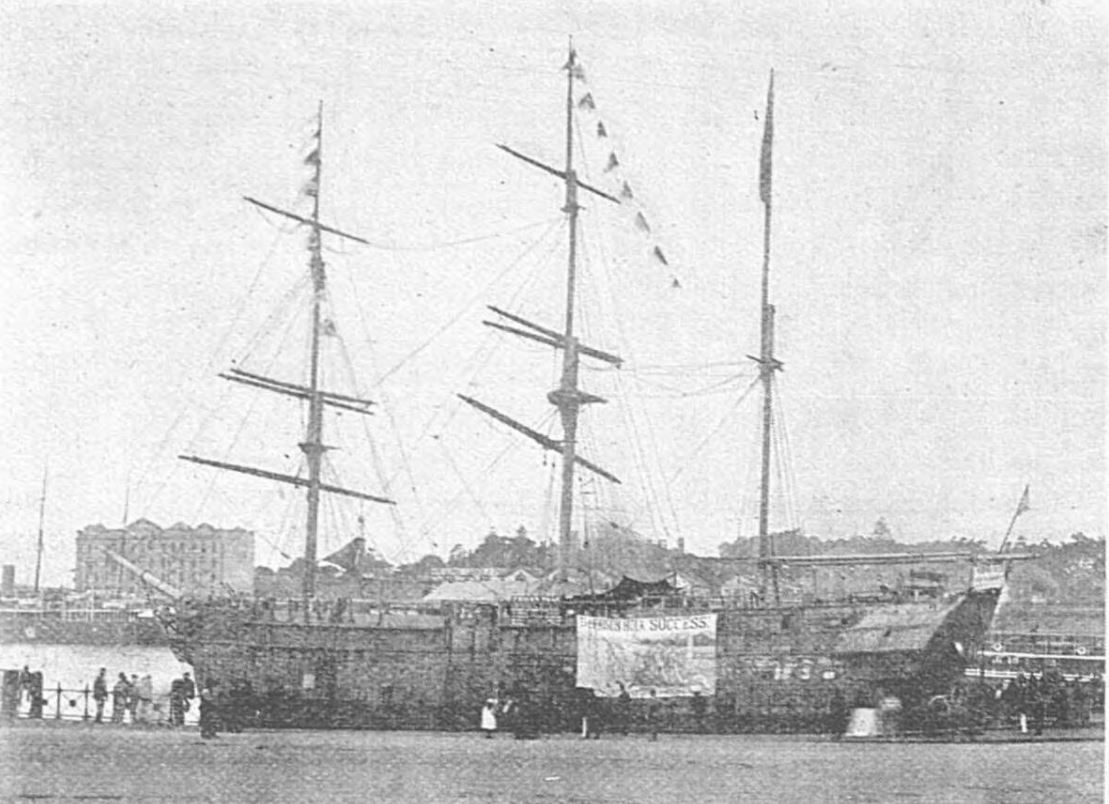

In September 1907, Maurice Downey for the Weekly Irish Times wrote about ‘Britain’s Last Convict Ship‘ the Success, which was then at anchor in the River Liffey. He observes how:

She serves to recall the shameful days, when as a floating Convict prison, she was not inaptly described by a Colonial writer, as an ‘Ocean Hell.’

In 1852 the Success, a merchant ship, arrived in Melbourne. It was the height of Victorian gold rush, and she was abandoned by her crew. An opportunity was quickly seized, as ‘she was acquired by the British Government to serve as a convict hulk at Hobson’s Bay,’ with 72 cells built to accommodate prisoners.

Maurice Downey relates how:

The unfortunate convicts who were confined below in ‘durance vile’ numbered 120, not one of whom escaped, and no wonder, seeing that they were completely at the mercy of 27 inhuman warders, who made their lives a very hell within their ocean habitation. A mere inspection of these cells and the instruments of torture with which they were amply furnished, is sufficient to make one shudder.

The Success was not the only prison hulk at anchor in Hobson’s Bay; she was joined by the President, Lysander, Sacramento and Deborah, to cope with Australia’s overflowing prison population. The Success, however, was notable for the ‘brutalities’ enacted on board, with prisoners subject to punishment by the dreaded cat-of-nine tails, with some receiving ‘as many as 100 lashes…with this hellish device.’

The Success | The Showman | 24 January 1902

Further means of punishment included:

Leg-irons, spiked iron collars, straight iron jackets, body irons, with hand-cuffs attached, were also used on some of the prisoners doing their sentences on board the Success. The spiked iron collar was a shocking means of punishment, and was so constructed that the wearer was obliged to remain always in a stooping attitude, which induced ill-health in many, and was the cause of death to not a few.

One observer recalled all the horrors of dungeons and prisons from across the world, ‘but not one of these is to be compared in refinement of cruelty and multiplication of horrors to the floating hells of Victoria.’

The Success’s career as a prison hulk came to an end with ‘the dreadful murder of Inspector-General Price by a large number of convicts.’ John Price was murdered by convicts from the Success in 1859, and the Weekly Irish Times notes how:

His murder was the direct means of leading to the abolishing of the hulk system in Australia, and more than one Australian paper stated openly that as he had sown the wind he had reaped the whirlwind.

Meanwhile, in 1868 the system of transportation to Australia finally ceased, but years of abominable cruelty, especially on the hulks, had left their mark on many.

‘Floating Chamber of Horrors’

But the Success was not to be left alone, even after she had been converted to a store hulk. In 1890 she was purchased by entrepreneurs with the intent of making her into a floating museum. They installed former Success prisoner Harry Power as a sort of showman for the former prison hulk, as reports The Sketch.

A ‘fine, hale old man,’ who had robbed ‘no fewer than 114 persons during’ his life of crime (although he was ‘especially polite’ to women), Power was a well-behaved prisoner and was released at the end of his sentence.

The Success | The Sketch | 14 June 1893

The author of The Sketch article, however, is unsupportive of the Success being made into a tourist spectacle:

A curio – interesting indeed; but her weather-worn face and draggled appearance tell us too plainly that she belonged to another age than ours. She has lived her life, done the duty allotted to her; pity it is she cannot be left in peace.

And although she was scuttled in 1891 with the venture being unsuccessful, she was soon after refloated and sent to tour the world, arriving in England in 1894. She was still touring in 1912, when crowds gathered at Cobh, Ireland, ‘to give a parting cheer to the venturous old ship,’ as reports the Suffolk and Essex Free Press. The Success was setting off to cross the Atlantic, where she was exhibited at the Great Lakes and San Francisco, before being sunk in 1918 or 1919, and then again refloated. The Success appeared at the Chicago World Fair in 1933.

The Success ‘lying at Waterloo Bridge’ | The Sphere | 4 January 1902

C. Fox Smith, writing for Britannia and Eve in 1936, was highly critical of this use of the Success, deeming her display to represent ‘a floating Chamber of Horrors.’ But for many the Success served as a reminder of a supposedly bygone age of cruelty, which saw the torture of prisoners and the creation of ‘heartrending tales’ from the tightly-packed cells.

But for Cecil King in The Sphere:

Even when entirely bereft of their masts and rigging, the old wooden hulks presented a picturesque and romantic aspect, and their almost total disappearance is one of the many sacrifices which we have made to progress.

We are not sure, given contemporary accounts and subsequent writings, exactly how ‘picturesque and romantic’ the hulks were. Indeed, they were quite the opposite, and they form an important part in the history of British and Australian crime and punishment.

You can find out more about prison hulks by searching in the pages of our newspapers; meanwhile our sister site Findmypast has a range of historic crime records, including prison hulk registers from 1811 to 1843. You can search these here.