The popularity of walking or ‘hiking,’ as it is termed, is amazingly on the increase. ‘Sabbath day journeys’ are undertaken by the youth of both sexes, armed with knapsacks. Starting from Waterloo to the Surrey hills and commons, where they walk, either in clubs or in private companies, or alone, all day, to return by train at night.

So relates The Sphere in the September of 1930 in an article entitled ‘Knapsackery on the Surrey Hills.’ Regarded as the ‘Phenomenon of the Post-War Youth,’ hiking saw an explosion of popularity in the early 1930s, as young walkers took to the hills of Great Britain and beyond.

Indeed, ninety years ago this summer, in 1931, hiking saw a ‘record year,’ with millions participating in this newest of outdoor pursuits. But why was hiking all of the sudden so popular? From where did the craze originate? And what was hiking actually like in the 1930s?

In this special blog, as we celebrate all things outdoors for the month of June, we will use our newspapers to explore the hiking craze of the 1930s, and how it characterised a generation of post-war young people.

Hikers in Pangbourne, Berkshire | The Graphic | 2 April 1932

Want to learn more? Register now and explore The Archive

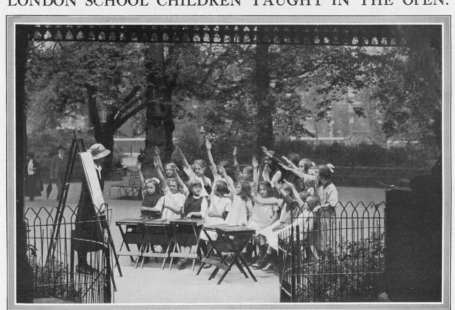

Everywhere The Hikers are Hiking

Picture the scene, it’s the early 1930s and suddenly you hear:

A clamour of voices and laughter, a clatter of heavy shoes, a burst of song waking the usual somnolent quiet of small country stations, and ruffling the traditional hush of an English Sunday into a shocked and startled astonishment. Hikers! Boys in shorts or plus fours or grey flannels; girls in bright-coloured jumpers, in breeches or brief skirts. A laughing, noisy crowd, surging into the train like an invading army – eight, ten, fifteen, twenty in a carriage. Flushed, tired, blown about by the wind and rain, burnt by the sun, and yet supremely, gorgeously, radiantly happy.

Hikers on Cobham Common, Surrey | The Sphere | 6 September 1930

A correspondent writing for The Sphere in June 1932 perfectly captures this ‘Phenomenon of the Post-War Youth,’ otherwise known as hiking. Suddenly, says Alan Kemp for The Sketch in 1932, ‘legs are being used with unprecedent vigour and versatility. Everywhere, in this country and in this age of mechanical transport, the hikers are hiking.’

Indeed, The Sphere in September 1930 tells of how hikers can be seen at most railway terminuses every Sunday, with ‘grey-green knapsacks carried by hikers…in marked evidence’ at Waterloo. There they would gather to take a train out to the country, go on a hike, and return that evening, whilst some preferred to take a longer trip.

Outward bound: a pair of hikers head to the country | The Sphere | 18 June 1932

And this outdoor activity had truly taken Great Britain and its young people by storm. At the end of the hiking season in October 1931, Peregrine for the Daily Mirror writes how:

Without doubt 1931 will be remembered as the record hiking year. In spite of generally deplorable weather, it is estimated that three million people have gone on a trek to the beauty spots of Great Britain, Ireland and the Continent. These enterprising ones, who have braved dreadful climatic conditions, have learnt to appreciate the joys of rambling.

To further illustrate the popularity of the new leisure activity, the population continued to hike even into the winter months. Janis Marlow for the Broughty Ferry Guide and Advertiser, 6 November 1931, penned an article entitled ‘And Still They Hike!,’ which described how:

One Sunday evening, quite recently, I stood at the London terminus of one of the railways and was amazed to see that almost every incoming train brought its share of hikers who had indulged in a day’s tramp in the country. Although many devotees of this comparatively new sport have already packed away their khaki shorts and rucksacks for the Winter months, it would appear that the true hiker sticks to his guns, or rather his feet, throughout the whole year. Wet skies and muddy roads do not dismay him, although judging by the dour expressions of many of the returning hikers, I could not help wondering whether they felt it a duty rather than a pleasure to tramp through miles of mud in pouring rain.

Hiking, it seemed, was here to stay. But from where had it originated?

Brazen Adventure

The Sphere in June 1932 observes how:

It is true that even in pre-War days people occasionally went for walking tours, or what they called ‘a tramp in the country,’ but they did it with a certain diffidence and unobtrusiveness, whereas the modern hiker in his khaki shorts and shirts open at the neck, with his untidy hair, his knapsack and long long stick, advertises himself without any false modesty or shame.

So whilst hiking had been popular before the First World War, it was not termed as such, and it had become a much more formalised activity, with its own specific clothing and equipment. Indeed, the actual word ‘hiking’ was held to ‘be a modern idiom come over from America,’ as The Sphere says, with its popularity formed under ‘the prevalent American influence.’

American hikers were, however, seen as being more extreme than their British cousins. Cecil Roberts in October 1931 for The Sphere reviews Touch and Go by American author Barbara Strike, a ‘hard-boiled hiking virgin,’ who had embarked on a five thousand mile trek across the United States, ‘getting lifts from lorry drivers.’ Roberts is somewhat dismissive of her ‘brazen adventure,’ expressing his gratitude that British female hikers were unlikely to follow in Strike’s bold footsteps.

Hiker with ‘a vengeance’ – Mr. John Wells | The Sphere | 1 November 1930

Meanwhile there was hiker with ‘a vengeance,’ Mr. John Wells, the son of American explorer Mr. Carberth Wells. The Sphere in November 1930 relates how Wells was ‘planning to walk around the world, accepting lifts only from such vehicles as are gratuitous.’ He was pictured starting from London en route to Dover, The Sphere remarking how hiking had reached ‘its apotheosis in such an undertaking.’

And although seemingly another American export, hiking’s origins could be found elsewhere, in both Europe and Asia.

Wandering Birds and Religious Pilgrimages

In July 1932 V. Sinclair for The Sphere wrote an article on ‘Where Hiking Was Born – The Wandervogel Movement in Germany.’ Wandervogel – in English, wandering bird – was an important German youth movement which originated in the late nineteenth century, as a protest against the increasing industrialisation of the country. Owing something to the Romantic notions from earlier in the century, it enabled young people to get back to nature, whilst preserving German traditions of music and folklore.

Sinclair goes on to describe the Wandervogel Movement in more detail, and its important link to hiking:

Rambling is, of course, the principal function of the Wandervogel movement; to tramp off, if possible, every Saturday or Sunday. And then, to crown the whole year, a long walking tour during the school holidays. Tramps of this kind are taken, first of all, in the homeland, in order that the young people may become acquainted with their own country; then they are extended across the frontiers, to show Germans living in neighbouring countries they are not forgotten and to confirm their ‘Germanity.’

The Wandervogel Movement was an important part of establishing a national identity and preserving traditions. But what was it like to go on a hike with the Wandervogel? Sinclair elaborates:

The parties are generally small and are under the control of one or two of the older hikers; i.e., the boys and girls are from ten to sixteen, and the leaders, perhaps from sixteen to twenty-one years of age. But there are also numerous individual hikers who, alone or in couples, sometimes on foot…roam over their small or large native soil…The group or party is, however, typical of the Wandervogel, as the movement is intended to promote association between the boys and girls of the various classes of society.

As part of the movement, ‘The individual has to learn to subordinate himself or herself to the community,’ whereby, for example ‘all must help when the meals are prepared for the party.’ But in 1932 the Wandervogel Movement’s days were numbered, especially when considering its particularly socialist ethos, as the long shadow of Nazism extended itself over Germany. In 1933 the Nazis outlawed the Wandervogel, along with German Scouting, instead promoting the Hitler Youth.

Meanwhile, hiking could also claim its origins some thousands of miles away in Japan. James Weymouth in March 1932 for The Sphere writes how:

Hiking has been the fashion in Japan for centuries. It owes its origin to the time-honoured custom of religious pilgrimages. As some of the most noted shrines are situated on the peaks of sacred mountains, a foundation had been laid for the sport of mountaineering which of late years and under foreign influence has acquired some popularity.

Indeed, Weymouth advocates hiking tours of Japan for the ‘less pretentious hiker,’ advising the European traveller to carry a ‘stock of extra food’ whilst walking. He describes the availability of hot baths in guest houses after a long day’s hike, which might be taken in a ‘varied panorama of mountain, forest, sea-coast and cultivated valley.’

A pilgrim in Japan, in the shadow of Mount Fuji | The Sphere | 19 March 1932

Others, however, highlighted how the tradition of hiking stemmed from practices much closer to home. The Sphere in September 1930 notes how rather than hiking being a ‘growth of a new habit,’ it was in fact representative of the ‘revival of an old one which characterised our grandfathers in the tramping days of good Queen Victoria.’

It is fair to say, that wherever hiking had originated from, it was here to stay. But what did a 1930s hiking trip entail?

The Art of Hiking

In April 1933 Jane May for the West London Observer proclaimed:

Hiking is an art, and, like all arts, it must be thoroughly mastered to be enjoyed. It is not the dress or the rucksack that makes a hiker, but rather the staying power of an individual. Learning to walk all day and to enjoy doing so – that is the art of hiking.

She advises that one should ‘keep up a steady even pace, moving freely from the hips.’ But despite her proclamation that neither dress nor rucksack a hiker makes, Jane May also gives advice on the type of equipment and food the hiker should be carrying. Such equipment, clothes and preparation, of course, marked the hiker out from walkers of old.

West London Observer | 21 April 1933

May goes on to suggest that the ‘hiker should be as nearly ‘self-contained’ as possible,’ for there might not be a ‘house or shop for miles’ once on a hike. She suggests bringing ‘very flat sandwich tins – no wider than a cigarette case,’ wooden cutlery, cardboard cups and paper cloths, ‘which can be burned after use’ (we would not condone this today).

Food is a subject upon which many hiking commentators tended to dwell. Jane May has suggestions for all types of sandwiches:

Raw beef sandwiches are very nourishing…Date sandwiches are another suggestion. Other fruit sandwiches include: bananas with a few drops of lemon juice; chopped nuts and prunes, also flavoured with lemon juice; nuts and raisins…

Meanwhile Janis Marlowe for the Broughty Ferry Guide and Advertiser advocates carrying a ‘supply of fruit, chocolate and a sandwich or two’ for those partaking in winter hikes, as well as taking advantage of a hot meal at a ‘wayside shop or inn.’ Whilst Peregrine for the Daily Mirror in July 1931 advises hikers to ‘take plenty of tea with them,’ and to ‘drink it hot at breakfast and at the end of the day, and take it cold on the wayside’ for a ‘stimulating and refreshing’ taste.

Daily Mirror | 18 September 1931

Peregrine also advocates the ‘Ask the Farmer‘ method of gaining food whilst on a hike. He writes how:

By reason of their excellent behaviour, hikers should have no difficulty in finding a friendly farmer who will allow them to camp out on his land and build up their fires. The same friendly farmer is sure to have new-laid eggs and fresh milk available for the campers’ breakfast. Eggs, country bread and butter and tea – what more does one require?

And almost all commentators seemed to agree: chocolate was necessary for any hike. Indeed, the Daily Mirror features an advertisement for ‘Rowntree’s Motoring Chocolate’ in July 1931. For as Mary Montgomery says:

A good tramp is the finest exercise…but’s bad to get over-tired. We insure against that by always taking some Rowntree’s Motoring Chocolate – nothing like it for keeping a spring in your step all day long.

Rowntree’s Motoring Chocolates | Daily Mirror | 24 July 1931

Sleeping Out

So when our tired hikers, deciding not to travel home to the warmth and comfort of their own beds, decided to carry on the hike the next day and bed down for the night, where did they stay?

Well, The Sphere in April 1931 comments on the prevailing fashion of ‘sleeping out:’

The latest development in the great increase of ‘hiking’ that has spread all over England in the past few years is the fashion of sleeping out. Parties bearing flea bags and blankets, provisions, and, on occasion, even gramophones and wireless sets, throng the slopes of the Surrey hills with the approach of clement weather, walking all day and resting by night. The Easter holiday, despite the cold snap that preceded it, offered an opportunity for alfresco activity of which the young public fully availed itself.

‘Call of the Great Outdoors’ | The Sphere | 4 April 1931

This new fashion for sleeping out has the hallmarks of today’s festivals, and indeed, with the addition of wireless sets and gramophones you can imagine the revelries which took place across the Surrey hills.

But for those who did not want to sleep out, or pitch a tent, the hiking revolution had precipitated a new movement – youth hostels. Peregrine for the Daily Mirror in May 1931 elaborates:

The inception of the Youth Hostels movement, which promised to cover the green places of the country with a network of cheap but clean rest houses, will do away with the necessity of carrying a heavy kit for camping.

The Youth Hostel Association was formed in 1930, inspired by a similar movement in Germany. Their aim, which remains the same today, was to give young people, particularly of limited means, the chance to enjoy the countryside, as well as the United Kingdom’s cities. And with the establishment of youth hostels across the country, more and more hikers could take to the hills and paths, safe in the knowledge that they would have somewhere to rest once their day’s efforts came to an end.

And meanwhile, this idea of affordability, given the moment in time, following the Wall Street Crash and the economic depression that followed, was key as to why hiking surged in popularity in the early 1930s.

A group of hikers with their ‘portable tent’ | Daily Mirror | 24 July 1931

As Peregrine writes for the Daily Mirror in October 1931:

In these times of financial stringency ramblers have discovered that a hiking tour – especially if camping out is possible – is the cheapest and healthiest of holidays.

He goes as far to warn hikers off from completing a ‘Continental hiking holiday,’ citing the unfavourable exchange rate, and instead advises his readers to ‘Ramble in Britain,’ just as they should be ‘Buying British.’

Misses 1931

Another important social element in the hiking revolution was the freedom that it afforded the young women who participated in the pursuit. Hiking permitted the wearing of shorts for women, still quite a taboo in society at the time, as well as the showing of bare legs!

Two women dressed in the height of hiking fashion | The Sphere | 18 June 1932

Peregrine for the Daily Mirror in May 1931 observes:

…we may expect to see even more girls enjoying the fun and exercise of a heel-and-toe holiday this summer. It is a mistaken idea that girl hikers need to be dowdy or dressed in a forbidding ‘utilitarian’ costume. Most of the London stores have now woken up to the fact that youth has found its feet and are selling complete hiking outfits – in which the dominant note is colour!

‘A Trio of Girls in Essex’ | The Sphere | 18 June 1932

He goes on to give advice to a potential female hiker, highlighting how ‘bare legs are…fashionable.’ This illustrates just how far society had come since, say, the end of the First World War. Meanwhile, for a young woman just starting hiking, Peregrine says:

The rucksack is important, for carrying the mac, night clothes and other necessities. Girls who are afraid of getting overtired will be surprised to find that the rucksack, once they have settled down after the first few miles, seems to be an actual aid to walking; but a light one is advisable.

The ‘tenderfoot’ hiker should first try a short hike, returning home at night, to find out if she is really an open-road girl, before trying to scale the mountains of North Wales!

Despite perhaps being a little patronising in its tone, there was a revolution here that was quite literally afoot. Women now had the freedom to go out and hike by themselves, unaccompanied, hiking having made that acceptable!

‘Hiking in the Highlands’ | The Sphere | 11 July 1931

‘Hiking in the Highlands’ | The Sphere | 11 July 1931

The Sphere, 11 July 1931, captured the spirit of this freedom, when it pictured a ‘trio of Misses 1931’ hiking in the Scottish highlands:

A trio of Misses 1931, knapsack on shoulder, staff in hand, stride barelegged along the border of a loch in Glen Dochart.

The excitement of this freedom to explore is palpable. And despite some platitudes – for wet weather hiking, the Ballymena Observer remarks ‘don’t forget that rain water is very good for your skin’ – the hiking revolution had helped to precipitate another – women’s right to roam.

Where Will It End?

Hiking, however, was not without its detractors. Whilst Alan Kemp for The Sketch proclaims how ‘the greatest enemy to hiking is the human heel,’ due to its proclivity for forming blisters, and worries about the burdens of carrying one’s equipment, to say nothing of the British climate, The Sphere published an article in June 1932 which bordered on the incendiary.

To begin with, it paints a merry picture of old England colliding with the new:

‘Them queer walking folk’ are familiar now in every village in England, viewed by the country people as somewhat eccentric and new-fangled in their ways, but accepted generally with tolerant if somewhat sceptical good humour. Their free and easy manners provide a constant pleasurable topic of scandal, the girls’ short skirts or breeches are examined with wondering curiosity, their laughter and noise are accepted with smiling indulgence, their general untidiness is regarded as just part of the game.

A hiking rally in Whatstandwell, Derbyshire | The Sphere | 18 June 1932

Whilst one country clergyman bemoans the young hikers’ lack of combs, graver concerns are voiced by the article:

There are other things also which seem a pity – the empty tins, the discarded matchboxes, the cigarette ends and bits of paper which disfigure the countryside, the disregard for other passengers in the trains and motor coaches, the inclination to ignore totally laws and restrictions, the want of attention paid to private property, a slightly socialistic tendency as regards the unassailable prerogative of youth.

Finally, the writer ends on an alarming note, as they discuss the passing of the Access to Mountains Bill, which they claim, would allow hikers ‘to roam at liberty over the downs and moors and hills of England, and leave hardly a corner immune from intrusion.’ They continue with this rather dystopian vision:

Within the last two years hiking has increased to such an extent and become so generally prevalent that is really a little difficult to see where it will end, and a little alarming to contemplate the extent to which it may grow. One begins to wonder whether the countryside, especially in the vicinity of big towns, will be large enough to accommodate the ever-increasing hordes of bare-legged, sunburnt boys and girls. The gardens and parks of great houses will no longer be private, country lanes will soon resemble crowded thoroughfares, country inns will be as noisy and crowded as popular Corner Houses, and older and staider folk, wishing to have a quiet Sunday walk, will have to restrict themselves to the silent streets of the deserted cities.

But this did not deter the hikers; nor, of course, was the countryside ruined, nor the the cities deserted. The love for hiking survived the Second World War, as Victor Bonham-Carter writes for The Sphere in November 1955:

Nowadays…there are mass treks along well-defined routes, hundreds of officially registered youth hostels, and the mapping and sign-posting of rights-of-way by the Statute.

And we owe this opening up of the British outdoors to those hikers of the 1930s, who pioneered a new and revolutionary pursuit which so many of us still enjoy to this day.