Nearly one hundred years ago athletes Harold Abrahams and Eric Liddell took the Olympic Games and the world by storm, their heroics on the track immortalised in the 1981 film Chariots of Fire.

But how were Abrahams’s and Liddell’s record-breaking feats reported on in the newspapers of the time? Were they celebrated in, say, the same way we celebrate our sporting heroes of today? In this special blog, we will explore the headlines behind the real Chariots of Fire, and in the process remember the ground-breaking feats of these two different athletes.

Want to learn more? Register now and explore The Archive

‘Our Olympic Chances’

The eighth modern Olympiad opened in Paris on 5 July 1924. On that same day, newspaper the Leeds Mercury was reporting on Britain’s ‘Olympic Chances,’ and how the country possessed a ‘strong team’ who were able to ‘rival the world’s best.’

At the heart of Britain’s athletic hopes were two sprinters: Harold Abrahams and Eric Liddell. The Leeds Mercury describes how:

Liddell, a product of Edinburgh University, is leaving the 100 metres to Abrahams, and has entered for the 200 and 400 metres. His style of running is not above criticism – he carries his head too high – but a fortnight ago he ran 440 yards in 49.54 sec, time good enough to carry him into the very first flight.

Liddell, the Montrose, Arbroath and Brechin Review tells us, was already ‘a household word in Scotland,’ having played rugby union for his country and established himself as ‘her foremost sprinter.’ Meanwhile the Coatbridge Express reveals that Liddell’s father was a ‘gymnast and fencer of marked ability,’ before becoming a missionary in China.

It was in China that Eric Liddell was born in 1902, and he inherited the same faith as his father before him. Furthermore, what the Leeds Mercury neglects to report is that Liddell left ‘the 100 metres to Abrahams’ because the heat was due to be run on the Sabbath, the sanctity of which Liddell refused to disrupt.

Eric Liddell’s faith was his most important inspiration; whilst his fellow athlete Harold Abrahams ran to overcome prejudice. His father was a Polish-Lithuanian Jew who had emigrated to Britain, and so Abrahams belonged to a minority, which still faced discrimination. Abrahams attended Cambridge University and was captain of the athletics team there, having also competed in the 1920 Olympics at Antwerp.

So by 5 July 1924 this largest of world’s stages was set, the Leeds Mercury describing several days later how ‘thousands of sportsmen…have gathered in Paris from the four corners of the world,’ competing on the ‘red-coloured track at the Colombes Stadium.’ And what an Olympic Games this was set to be.

The ‘Mighty Abrahams’

On 8 July 1924 the Leeds Mercury reports how:

To-day on the red-coloured track at the Colombes Stadium records were being broken or equalled throughout the day, and no sooner had the megaphone man announced one new record and the cheering in many languages had died away, than the booming voice echoed over the vast arena announcing another world’s best.

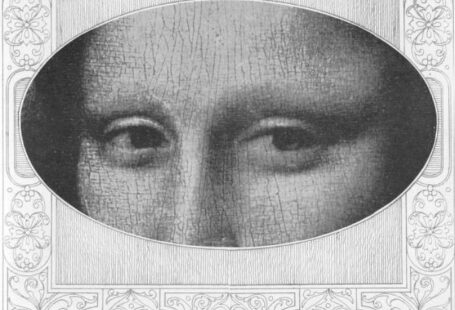

Harold Abrahams | The Sketch | 16 July 1924

And one of these world’s best was set to be Harold Abrahams, who competed in the 100m final on 7 July 1924. The 100m title had always traditionally belonged to the United States, as the Athletic News relates on 14 July 1924:

The Americans had come to look upon the 100 metres race as their own, and not without good reason. Out of the six races in the Games they had won five, the only break being in 1908 when R.E. Walker, South Africa, won. They have a remarkable number of good men at the distance…it is almost a fetish with the Americans, who are tireless in their efforts to find short distance men.

Indeed, Abrahams was set to face ‘more than a quartette’ of them in the final, including 1920 title winner Charles Paddock, whom Abrahams had beaten ‘by inches’ in the semi-final, having ‘got away badly’ to win from fourth place.

The Athletic News sets the scene for the final, describing the ‘perfect silence’ as the finalists ‘had knelt down at the start point.’ The report continues:

The men got down and as the pistol cracked they rose to a beautiful start. Abrahams was slow in getting away (the previous heat he lost a yard and yet won), but at half way he was just level with Scholz and Bowman. He fought with characteristic determination. His long, raking stride, his forward body movement and beautiful arm action told its story.

Harold Abrahams | Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News | 19 July 1924

The crowd now had found their voices, the Leeds Mercury recalling a ‘long roar of wild cheering throughout the race,’ as Abrahams, ‘inch-by-inch…forged ahead, and seemed to gain half-an-inch at each stride from the half-way mark.’

The Athletic News once again picks up the narrative:

Twenty yards from the line he was in front by a yard; three yards from the line he was a yard in front, and so he broke the worst with the distance in hand, and Scholz was his nearest opponent.

Harold Abrahams was victorious, the Olympic champion, having equalled for the third time in two days the Olympic record for the 100m. The Athletic News hailed him as the ‘mighty Abrahams,’ and ‘the hero of the Olympiad.’ Meanwhile, the Leeds Mercury lauded the ‘beautifully run race throughout.’

And the crowd went wild for him. The Leeds Mercury reports on the ‘indescribable enthusiasm’ with which Abrahams’s victory was met, the cheering lasting ‘some minutes, a truly international tribute.’ Meanwhile the Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer writes, a day after Abrahams’s triumph, how, after a race of ‘tremendous thrills:’

The scene of enthusiasm was beyond description, by far the greatest ovation yet seen here, and to their credit be it noted that the American sprinters and the Americans in the stand joined whole-heartedly the cheering and congratulating.

The sporting Americans were indeed profuse in their praise, with the Belfast Telegraph reporting how ‘crack Californian sprinter’ Charles Paddock was ‘bubbling over with enthusiasm concerning the feats of Abrahams.’ Paddock is reported as saying:

‘We think,’ he said, ‘your Harold Abrahams one of the most wonderful sprinters in history; in fact, we have never seen a better man in action.’

Indeed, as The Sketch remarked, Abrahams could now ‘claim to be the world’s fastest sprinter.’

‘The Most Dramatic Race Ever Seen’

Following on from Abrahams’s success, Eric Liddell was set to compete in the final of the 400m on the 11 July. The Shields Daily News, a day later, describes the scene, with the pipers of the Cameron Highlanders playing in the middle of Colombes Stadium just before the ‘thrilling final,’ appropriate for the flying Scotsman himself.

The Shields Daily News reports on the race:

There was a gasp of astonishment when Eric Liddell, one of the most popular athletes at Colombes, was seen to be a clear three yards ahead of the field at the half-distance. Nearing the tape Fitch and Butler strained every nerve and muscle to overtake him, but could make absolutely no impression on the inspired Scot.

Eric Liddell at the finish line of the 400m | Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News | 19 July 1924

With twenty yards to go Fitch seemed to gain a fraction, but Liddell appeared to sense the American, and with head thrown back and chin thrust out in his usual style he flashed past the tape to win what was probably so far the greatest victory of the meeting. Certainly there has not been a more popular win. The crowd went into a frenzy of enthusiasm.

Again, the Union flag was flying in ‘proud majesty over the Colombes Stadium,’ following the ‘great victory’ of Eric Liddell. He had run his 400m final in 47 3/5 seconds, setting ‘the third world’s record in two days for this event.’

Reflecting on the race on 19 July 1924, the Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News writes how ‘This was probably the most dramatic race ever seen on a running track.’ In taking gold, furthermore, Liddell had become only ‘the second Scotsman to win an Olympic title, the only other being W. Halswell, who won the same race in 1908.’

Eric Liddell | The Sphere | 19 July 1924

Liddell, however, was not without his doubters – remember the scepticism of his running style in the Leeds Mercury? Indeed, Charles Paddock remarked:

‘We were a bit surprised in the success of Liddell, for, after the pace we set, we hardly expected him to go through.’

But Liddell had overcome his doubters with his determination, and now was described as ‘the greatest quarter miler ever seen on the track,’ as relates the Montrose, Arbroath and Brechin Review. And having stayed true to his Christian beliefs throughout the Olympics in Paris, avoiding racing on the Sunday, it was only appropriate that he celebrated the following Sabbath by conducting the service and preaching a sermon at ‘the Scottish Church in Paris.’

Shields Daily News | 12 July 1924

Crowned With Laurels

Both men were feted when they return to Britain, but Liddell garnered especial accolades upon his return to Edinburgh, where he was set to graduate. On 17 July 1924 the Dundee Courier ran the headline ‘Laurel Wreath for Liddell,’ as that very day Eric Liddell was to graduate from Edinburgh University with a degree in science, capped with a ‘wreath of laurel.’

The Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News reports how the victorious athlete was ‘chaired’ (carried in a chair) to ‘St. Giles Cathedral, where the graduation service was held.’ Liddell was then set to be entertained by a myriad of different dinners, including one held on 18 July 1924.

Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News | 26 July 1924

The Dundee Courier relates how Lord Sands would be presiding over this particular dinner, which was:

…proposed to welcome our brilliant young athlete, Mr. Eric H. Liddell, on his return to the city from the Olympic Games in Paris, and to express the widespread admiration for his remarkable athletic achievements, and also for his devotion to principle in this connection as a reverend upholder of the Christian Sabbath.

On 25 July 1924 Liddell was then entertained ‘at luncheon by the Lord Provost, councillors, and citizens of Edinburgh,’ as relates the Aberdeen Press and Journal. And his name was also being ‘proclaimed in many pulpits.’ The Edinburgh Evening News reports on the service held at St. George’s United Free Church, conducted by the Reverend Doctor James Black, who said:

‘I would just take young Eric Liddell. It took real grit to make the stand which Liddell did, out of the fulness of his convictions, for the reverence and the sanctity of the Lord’s Day.’

But despite such adulation and adoration, Eric Liddell remained humble. ‘Answering the demand for a speech,’ the Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News tells of Liddell’s words:

‘Over the entrance to the University of Pennsylvania there are these words: ‘In the dust of defeat as well as in the laurel of victory there is glory to be found if one has done his best.’

Meanwhile, Harold Abrahams was focussing on athletics, with an eye on the next Olympic Games, which were to be held in Amsterdam. The Belfast Telegraph quotes the gold-medal winning athlete as follows:

Let us not spend too much time in praising the prowess of our athletes who were successful at Paris. Let us rather look to what we are to do at the games at Amsterdam in 1928.

But soon, the press was swirling with rumours that Abrahams was set to give up his athletics career, having suffered from a nervous breakdown. However, Abrahams addressed this rumour in early August, the Hartlepool Northern Daily Mail reporting how he was ‘simply in need of a rest.’

In addition to this, Abrahams was studying law and intending to ‘practise at the Bar,’ and so he feared that he might not be able to both ‘follow that profession and maintain first-class form on the track.’ He told the press:

The odds are I shall not run again…but I expect that in 1928 I shall try to get to Amsterdam.

Abrahams’s words proved to be sadly prophetic. In 1925 he broke his leg whilst long jumping, ending his athletic career. He went on to work as an athletics journalist for forty years, reporting on the 1936 Berlin Olympics, and becoming president of the Jewish Athletic Association. He passed away in 1978, aged 78.

Eric Liddell too would not compete in another Olympics, for different reasons. In 1925 he travelled to China to work as a missionary. During the Second World War, when Japan invaded China, Liddell was interned at Weihsien Internment Camp, from where he would never return. Exhausted, and suffering from a brain tumour, the celebrated Scottish sprinter passed away in February 1945, five months before liberation.

Two different stories, two very different men, but each celebrated for their remarkable achievements in the 1924 Paris Olympics, indeed worthy of the film they inspired.

Belfast Telegraph | 25 April 1981

We hope you enjoyed looking at the headlines behind the real Chariots of Fire. What headlines will you discover in the pages of our Archive? Let us know.