The events of the early hours of 28 June 1969 in Greenwich Village, New York, where LGBTQ+ patrons of the Stonewall Inn fought back against police violence, would reverberate not only across the United States, but the world, and mark an important turning point in the fight for LGBTQ+ rights.

The Stonewall riots in turn led to the birth of the Pride movement, where members of the gay and lesbian community took to the streets to demand an end to discrimination. This was a watershed moment in the fight for LGBTQ+ equality; members of the gay and lesbian community were making themselves visible and vocal in ways that could no longer be ignored.

And in the United Kingdom, the first march for gay rights saw 150 men walking through Highbury Fields in North London. But the first official UK Gay Pride Rally was held on 1 July 1972, the date chosen for its proximity to the anniversary of the Stonewall riots, with approximately 200 people in attendance.

Register with us now and see what stories you can discover

In this special blog, we will look a the first 20 years of Pride rallies in the United Kingdom, using newspapers taken from our Archive. We will trace the Pride movement through its formative years, where members of the gay and lesbian community faced widespread discrimination, through to the 1980s and 1990s, when rallies became better attended and supported. We will also look at how the Pride movement responded to the abject intolerance of Section 28, which was introduced in 1988 and prohibited the ‘promotion of homosexuality’ by local authorities in Britain.

Register now and view three pages for FREE

1972-1974 – ‘Calls For A Proud Rally’

The first ever Gay Pride rally in the United Kingdom, held on 1 July 1972, garnered little if any press attention, demonstrative of the battle the gay and lesbian community had on their hands for raising awareness of their struggle for equality.

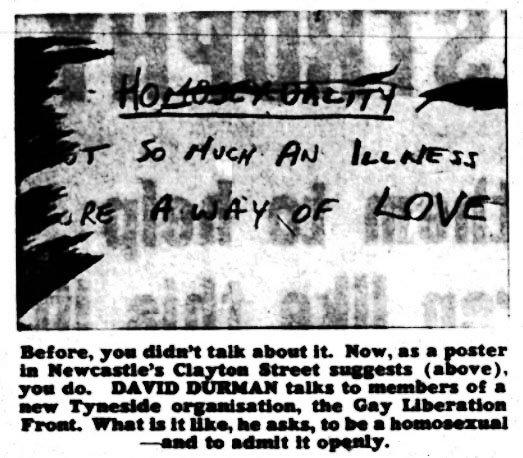

However, the Gay Liberation Front (GLF), a gay liberation group that was founded in New York in 1969 following the Stonewall riots, with Britain’s own branch being established a year later, was reported on by the British press in 1972.

The Newcastle Journal on 28 July 1972 covers the ‘flourishing’ GLF branch in Newcastle, the organisation having held a dance a few day previously. The dance was attended by 80 members of the gay community, and the newspaper notes how ‘Five years ago the dance would never have been allowed.’

The article addressed the struggles faced by gay men at the time, including a quote from Peter (not his real name, symptomatic of the prejudices the gay community faced due to being out during that era), who said: ‘All I can say is that I have to be gay. All I hope is people can accept that. That’s all I want – acceptance.’

A year later in 1973 we found the first mention of Gay Pride in our newspapers, from the Hammersmith & Shepherds Bush Gazette, 5 July 1973, which described the ‘programme of events’ for Gay Pride Week:

…events included a picnic in Hyde Park, a riverboat shuffle and an open air disco on Clapham Common. On Friday the GLF held a demo in Fleet Street. They met outside the Law Courts to distribute leaflets around newspaper offices and talk to ‘pressmen.’

The 1973 Pride Week would culminate in a ‘Gay Pride Rally and March from the Embankment to Hyde Park,’ where the picnic was held.

In 1974 Sandra Bisp for the Reading Evening Post reported on another Gay Pride event, this time held in November by the Campaign for Homosexual Equality (CHE). This demonstration was held ‘in a bid to lower the age of consent’ for gay men from 21 to 16. Although the Sexual Offences Act of 1967 had made consenting sexual relationships between gay men legal, the age of consent was not in line with heterosexual relationships.

CHE had called for ‘proud rally’ in this cause, hoping that gay men and women would join the ‘rally and admit they are gay.’ It was hoped that the majority of their 4,600 members would travel to London, with 50 members of the Manchester gay and lesbian community alone joining the demonstration.

1975-1979 – ‘Drawing Public Attention To Discrimination’

As the 1970s went on gradually more press attention was being directed towards Pride events, with adverts for and coverage of Pride rallies appearing in newspapers, generally at more local level.

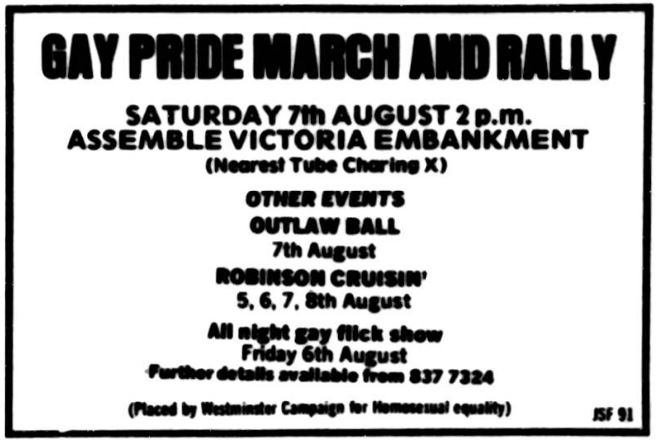

In August 1976 the Fulham Chronicle included an advert for a ‘Gay Pride March and Rally’ which was being held on 7 August 1976. The advert was placed by the Westminster Campaign for Homosexual Equality, and attendees were encouraged to assemble at the Victoria Embankment for the rally.

Meanwhile, the Kent & Sussex Courier reported on 13 August 1976 how 2,000 members of the gay community took part in the march, noting how six members of the Tunbridge Wells CHE group were in attendance. The newspaper described how:

The aim of the march was once more to draw public attention to discrimination against homosexuals in criminal law, employment and society. The march ended at Hyde Park where speeches were made by various prominent CHE supporters.

By 1979, the 10th anniversary of the Stonewall riots, the Pride movement had spread across the country, with the Hammersmith & Shepherds Bush Gazette reporting in June of that year how gay and lesbian organisations ‘all around the country are trying to increase public awareness of their cause’ during Pride week. The newspaper, however, also reported on the problems the gay community faced in doing this:

Although a wide range of activities is planned in most areas, the programme for West London is more limited because of a lack of support for local gay organisations. A spokesman for the Gay Pride Week Committee said a number of gay groups in the Acton, Ealing and Chiswick areas had folded in the last few years because of dwindling support.

It was most likely not apathy that prevented support for such local gay organisations. Many gay men and women were afraid to come out, afraid of the discrimination they might face, in a society that was still intolerant of their sexual orientations. ‘Coming out,’ therefore, was at the heart of rallying call of Pride during this time, an incredibly brave step to undertake.

Meanwhile, we found a photograph of the 1979 Gay Pride rally from the Birmingham Daily Post, 2 July 1979. It is captioned:

Police accompany a carnival making its way through London yesterday at the end of International Gay Pride Week, an event marking the tenth anniversary of the Stonewall riots in New York which resulted in the birth of the Gay Liberation movement.

It was a profound anniversary, on the eve of a new decade that would see greater visibility for the gay community, but perhaps even greater challenges.

1980-1984 – ‘Coming Out’

By 1980, Pride events had become more and more visible across the pages of newspapers from across the United Kingdom. For example, on 21 June 1980 the Aberdeen Evening Express reported on the activities of the Aberdeen Gay Pride Week Committee, who for the second year in a row had been ‘busy organising events for Gay Pride Week.’

The group had laid on a plethora of events, which would culminate in a trip to London ‘for the Gay Pride march:’

The Lesbian Group start off tomorrow by having a coffee afternoon. On Monday Aberdeen Gay Activists’ Alliance are holding a public meeting in the Music Hall at 8 p.m. On Tuesday the Lesbian Group are having a night out. Aberdeen University Gay Society are holding an art exhibition fair in the Music Hall on Wednesday from 11 a.m. till 4 p.m. On Thursday the Scottish Homosexual Rights Group are having a disco.

Meanwhile, Pride made national press that year when the Sunday Mirror reported how ‘hundreds’ of the gay community had ‘marched on Bow Street police station in London yesterday, demanding the release of people held earlier in a Gay Pride Week parade.’ It was a short sentence, and leads to many more questions than answers. Were those who marched during Pride more likely to be unfairly arrested? What was clear, however, was that there was still much to do in raising awareness of the struggle for gay equality.

And Pride by 1980 had reached a different medium – that of television. In July 1980 a BBC 2 programmed called ‘Coming Out’ was aired, and reviewed by Roy Shepherd for the Belfast Telegraph. This was especially powerful as consenting sexual relationships between gay men were still illegal in Northern Ireland at this time, with Shepherd addressing how such relationships were viewed as ‘both sins and crimes.’

However, Shepherd explains the premise of ‘Coming Out,’ which followed five young gay men and their stories of ‘coming out’ to ‘family, friends and employers, people who might be uncomprehending, vulnerable or even vindictive.’ The film, Shepherd notes, ‘was made during Gay Pride Week 1979 when thousands of young men and women came out to the streets of London to proclaim that they were ‘gay.’’

In 1981 the Reading Evening Post looked across the Atlantic to report on Hollywood’s National Gay Pride Week, where it was estimated that 75,000 people had taken to the streets to mark the start of the week. Gradually, Pride was becoming part of the fabric of the British press; it was event that had to be reported on, and clamoured for attention. 75,000 people could not be ignored.

Closer to home, London’s annual Pride event looked a little different in 1981. It was held in Huddersfield, as Mike Homfray, writing to the Huddersfield Daily Examiner in July 1989, explained:

…[in] 1981 when gay men in Huddersfield issued broadsheets, ‘A Cry for Help,’ detailing the systematic investigation into the lives of many local gay men after constant harassment and raids at a local gay nightclub. This aroused attention not only locally but nationally, and eventually the Gay Pride March of 1981 was held in Huddersfield as a protest – a national demonstration…

Pride was held in Huddersfield as an expression of solidarity, directly addressing the police discrimination in the town. Moreover, Pride showed itself to be adaptable, addressing issues affecting the gay community as they arose. And this adaptability, this resilience, would come to be vital as the 1980s progressed.

1985-1989 – More Battles – The AIDS Pandemic and Section 28

By 1986, Pride in London had become known as the ‘National Lesbian and Gay Pride Festival,’ and on 19 June 1986 the Kensington Post reported how there would be ‘more than 400 events around the country’ marking Pride week. The newspaper, meanwhile, noted how more than 20,000 people attended the 1985 rally, a huge increase in the number of attendees from a decade before.

But the gay and lesbian community still faced prevailing discrimination. In June 1986 the Daily Mirror labelled the Lesbian Strength Gay Pride Week ’86, held in Hackney, as ‘controversial,’ citing one Conservative councillor’s view that the event represented ‘seven days of shame and sin.’ There was still so much to be done in gaining gay and lesbian equality, and the gay and lesbian community would not rest until equality could be achieved.

Indeed, in May 1987 the Hammersmith & Shepherds Bush Gazette reported how ‘Lesbian and gay protestors picketed Labour councillors to force them to keep their promises.’ The Hammersmith protestors were calling out a number of issues, such as the cancellation of the ‘gay and lesbian working party for the foreseeable future,’ as well as the refusal of the placement of a Pride banner across a local street.

Meanwhile, during Pride that year entertainment stars threw themselves into the occasion. The Coventry Evening Telegraph on 20 June 1987 related how ‘dazzling’ singer Hazell Dean had ‘lent her support’ to a concert on London’s South Bank, ‘to mark the climax of Gay Pride week.’ Furthermore, 1960s star Julie Felix came out during 1987 Pride, as reported the Daily Mirror. Between ‘songs she declared solidarity with her ‘lesbian sisters.” Also on the bill that year was Sandie Shaw.

However, the 1987 Pride events were marked by the AIDS crisis, and the gay community rallied to raise awareness of the pandemic. The Kensington Post on 25 June 1987 threw a ‘spotlight’ on some of these efforts during Pride week:

A GAY Pride Week disco in support of the AIDS charity London Lighthouse, is to be held at St. Clement and St. James’ community centre in Sirdar Road, North Kensington on Friday, from 8 p.m. to 11 p.m.

And then on 24 May 1988 the gay and lesbian community was struck a further blow with the introduction of Section 28, the first anti-gay law to be passed since 1885. Section 28 saw local authorities being banned from ‘promoting homosexuality by teaching or publishing material.’ The discriminatory clause, which was in place as late as 2003 in England and Wales, caused outrage, with lesbian protestors abseiling into the House of Lords to demonstrate against it.

However, some local authorities in 1988 were prepared, during Pride week, to take a stance against Section 28. The Ealing Leader on 17 June 1988 reported how Ealing Council had provided a grant towards Gay Pride week, citing Councillor Len Turner’s support of the gay and lesbian community, and how he believed that it was ‘vital for everyone to feel they have a place in society.’

Turner told the press, in defence of the grant for Gay Pride week, how:

The point of the week is to break down prejudice and discrimination. We can’t just trust that prejudice will all go away. People do not necessarily have equal access to what society has to offer. As a Council we must continually strive to provide a frame work within which people can achieve their full potential and can be recognised for their individual merits.

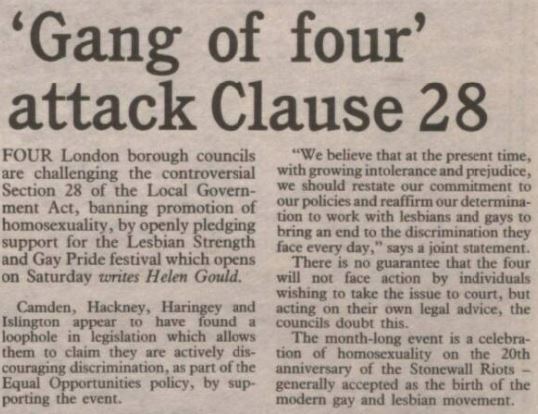

In 1989 Len Turner was joined by ‘a gang of four’ London borough councils (Camden, Hackney, Haringey and Islington), who as entertainment newspaper The Stage reported, were ‘challenging the controversial Section 28’ by ‘openly pledging support for the Lesbian Strength and Gay Pride festival.’ Their support was particularly poignant as the 1989 Pride week marked the 20th anniversary of the Stonewall riots.

Meanwhile Ealing council continued to pledge their support to the gay and lesbian community and Pride, as the Ealing Leader reported in June 1989. Various exhibitions, films and poetry readings were held across Ealing and Southall, the newspaper relating how:

Ealing is committed to providing good quality services for lesbians and gay men throughout the work of the council, as part of its policy of equal opportunities for all sections of the community.

The 1989 Lesbian and Gay Pride rally was attended by 30,000 people, as reported the Huddersfield Daily Examiner, with twenty gay men attending from the town, which had hosted the event eight years before. Their trip to Pride was organised by the Huddersfield Gay Switchboard, and the Irish Independent on 26 June 1989 described the demonstration as ‘peaceful.’

1990-1992 – ‘A Wonderful Day’

The power of Pride was growing as the 1990s began, and the 1990 London event drew members of the LGBTQ+ community ‘from across the country,’ as reported the Westminster & Pimlico News.

Across the Atlantic in New York, marking 20 years since the first Pride events were held in that city, the Nottingham Evening Post reported how the Empire State Building was set ‘to be lit up with lavender lights to mark New York City’s Gay Pride Weekend later this month.’

And whilst Pride events were well established in England and in the United States, they were not so much in Northern Ireland, where the gay and lesbian community still faced widespread discrimination. But Pride came to Northern Ireland in 1991, as Neil Mulholland for Sunday Life reported on in June 1991:

Gay men and lesbians took to the streets of Belfast yesterday in the first-ever public demonstration in Northern Ireland by homosexuals. Just over 50 men and 25 women, accompanied by children, marched from the Art College to the Botanic Gardens under the banner ‘Gay Pride Belfast 1991.’

Spokesperson Niall related the difficulties of organising the march, which had taken place eight years since consenting gay sexual relationships were legalised in Northern Ireland. He commented on how ‘Northern Ireland is very repressed sort of place.’ Sadly, Mulholland described how the inaugural Northern Irish Pride event was ‘shadowed by a larger and much older band of grim-face protestors,’ who heckled the Pride parade.

In London, however, the Lesbian and Gay Pride Festival continued to go from strength to strength, the Westminster & Pimlico News reporting how there was ‘no hitch in [the] Gay Pride parade.’ Indeed, more than 45,000 people were in attendance, gathering at the Victoria Embankment, before marching through Whitehall and Parliament Square and then ‘rallying in Kennington Park.’ Spokesperson Kevin Hunter commented:

It was a wonderful day. Police were brilliant and dealt with the few small problems we had very well.

The next year, in 1992, Pride returned to Belfast, as reported Sunday Life. There were ‘more than 100’ people this time who participated in the ‘Gay Pride Dander,’ with spokesperson Sean McGouran enthused by the turnout:

This was another splendid effort by gay people in Belfast and their friends from the rest of Ireland and further afield. Our numbers were up on last year – and so was the volume. We were even more noisy and cheerful.

Banners held high during the ‘Dander’ included those from ‘the Lesbian Line Belfast, Gay and Lesbian Equality Network (Dublin), Queen’s University, Belfast Students’ Union, the Socialist Workers’ Movement and NI Gay Rights Association.’

The Republic of Ireland followed suit, where gay relationships were not legalised until the following year. As the Irish Independent reported, a Lesbian and Gay Pride Parade took place on 4 July 1992, in order ‘to heighten public acceptance’ of the gay and lesbian community.

And London in 1992 hosted the first ever Europride, which the Westminster & Pimlico News in July 1991 heralded as ‘the lesbian and gay event of the decade.’ 100,000 people attended this event, 20 years after the first ever Pride event in London. By 1996, the event was renamed Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Pride, and is known today as Pride in London.

And what had changed in those first twenty years of pride? From hundreds to a hundred thousand, attendance had gone up, and those who attended and organised Pride events forced themselves in to the pages of the press who were at one stage apathetic and even disapproving of their cause. Pride made and continues to make LGBTQ+ issues visible, and it is necessary to remember those pioneering members of the LGBTQ+ community, from those who rioted at Stonewall to London’s first Pride, who made Pride possible, who made Pride into a pageant of celebration, visibility and equality, and we can trace this shift through the pages of our newspapers.

Register with us now and see what stories from LGBTQ+ history you can discover