On 1 December 1900 the Sunderland Daily Echo and Shipping Gazette reported on ‘The Death of Mr Oscar Wilde:’

The Paris correspondent of the Dublin Evening Mail telegraphs that Mr Oscar Wilde died yesterday at three o’clock in the Latin Quartier. He had been suffering for some time. Two days ago he became unconscious. Six weeks ago he underwent an operation, which appeared to have been successful, but a complication which followed proved fatal.

The death of the poet, playwright and novelist marked the end of what the newspaper dubbed a ‘chequered career,’ after Wilde’s trial and conviction for ‘gross indecency’ some five years before. His flourishing career never recovered, and he lived as an exile in France after his release from Reading Gaol in 1897.

Register with us now and see what stories you can discover

In this special blog, as part of Pride Month during which The Archive has been celebrating LGBTQ+ history, we will trace the evolving attitudes to Oscar Wilde in the months, years and decades after his death. Using newspapers from our collection, we will look at how Wilde was regarded at the time of his death, and in the years following. We will examine how he was seen as tragic, flawed, figure, and how attitudes began to change towards him as his work was slowly once again celebrated, as it once had been during his lifetime.

Register now and view three pages for FREE

The Death of Oscar Wilde

The Sunderland Daily Echo and Shipping Gazette presented quite a measured, albeit euphemistic, account of Oscar Wilde’s death and career:

He was the originator of the aesthetic movement of 21 years ago. He was fairly prolific as a writer and a dramatist. In 1892 his comedy entitled ‘Lady Windermere’s Fan,’ was warmly received in London dramatic circles, and ‘A Woman of No Importance,’ in 1893, had an even greater reception. Other dramas were also successful, but their course was suddenly cut short by the appearance of the author in the law courts.

Other newspapers, however, presented the death of Wilde in heightened, hyperbolic terms, contrasting his fame with his dramatic fall from grace:

Oscar Wilde died in Paris on the afternoon of the 30th ult. from meningitis. The melancholy end to a career which once promised so well is stated to have come in an obscure hotel of the Latin Quarter. Here the once brilliant man of letters was living, exiled from his country and from the society of his countrymen. The verdict that a jury passed upon his conduct at the Old Bailey in May, 1895, destroyed for ever his reputation, and condemned him to ignorable obscurity for the remainder of his days.

This account of Oscar Wilde’s life and death appeared in the Cannock Chase Courier on 8 December 1900, describing how when the writer was released from prison he ‘was broken in health as well as bankrupt in fame and fortune.’ The newspaper went on to suppose how death had ‘soon ended what must have been a life of wretchedness and unavailing regret.’

But even this report from the Cannock Chase Courier, drenched as it is in its high moral criticism, could not detract from Oscar Wilde’s genius. The newspaper goes on to laud Wilde’s ‘power of mind,’ and how he:

…was known as a poet of graceful distinction; as an essayist of wit and distinction; later on as a playwright of skill and subtle humour. A novel of his, ‘The Picture of Dorian Gray,’ attracted much attention, and his sayings passed from mouth to mouth as those of one of the professed wits of the age.

This dichotomy, of the disapproval of Wilde’s sexuality coupled with the admiration of his work, would fuel accounts of the writer in the years to come. And whilst Wilde lived, it would be the former that won out, but once he had died, admiration would slowly begin to outweigh censure.

A ‘Quiet and Simple’ Ceremony

Meanwhile, the Dundee Evening Telegraph on 2 December 1900 painted a sympathetic portrait of the last days of Oscar Wilde, describing how:

Two kind friends – Mr Robert Ross and Mr Turner – nursed him, whilst Father Cuthbert Dunn, one of the British Catholic chaplains from the Avenue Hoche, administered the customary rites of the church. Oscar Wilde tried to articulate the prayers, which accompany extreme unction, and his deathbed was one of repentance.

Perhaps this sympathy was derived out of Wilde’s reported repentance, but the newspaper went on to report how the writer’s funeral would be held in the Bagneux Cemetery on 3 December 1900. Wilde’s resting place would be marked by a ‘small cross,’ with an inscription reading: ‘Cigit Oscar Wilde, poete et auteur dramatique. R.I.P’

The Cardiff Times on 8 December 1900 reported on the ‘Funeral of the Late Oscar Wilde,’ which took place at the Church of St. Germain de Pres. The office of the dead was read by Father Herbert, who ‘had received Mr Wilde into the Roman Catholic Church a few days before death.’ The Cardiff Times went on to describe how:

The concluding portion of the service was conducted at the Cemetery of Agnux, where the remains of the deceased author were interred. The ceremony was very quiet and simple, but the coffin was covered with beautiful wreaths of natural flowers, and one of evergreen laurels sent by English and French admirers of the dramatist.

The newspaper also listed those in attendance at the funeral. One of the mourners was Lord Alfred Douglas, Wilde’s lover.

A ‘Most Perplexing and Pathetic Figure’

With Oscar Wilde finally laid to rest, his name continued to reach the pages of the press. In May 1901 the Stockton Herald, South Durham and Cleveland Advertiser told a ‘characteristic story of Oscar Wilde.’ The writer was at a ‘society crush’ talking to a ‘charming society lady,’ when he was interrupted by a ‘small man’ who greeted Wilde by saying: ‘Hello, Oscar, d’you know, every time I see you, you are getting fatter and fatter.’

The newspaper details what supposedly happened next:

‘I don’t know who you are,’ replied Wilde scornfully, ‘but every time I see you, you get ruder and ruder.’ The little fellow vanished. ‘Can you tell me,’ asked the apostle of aestheticism, turning to the lady, ‘who is that dreadful little cad?’

With frigid glance and haughty manner she replied, ‘That, Mr. Wilde, is my husband.’ ‘Is it, indeed?’ said he, unabashed, ‘then what a pity you don’t teach him better manners.’

It was as if the drama and the tragedy of Wilde’s later life had never happened, as he was celebrated once more for his irreverent wit.

And Oscar Wilde’s work was once again celebrated with the publication of his posthumous letter De Profundis, which the St James’s Gazette described on 2 December 1904 as a ‘book of great interest.’ Indeed, the same newspaper on 23 February 1905 reflects, following the publication of De Profundis, how there had ‘no greater tragedy in literature than that which happened at the Old Bailey ten years ago.’ It was not to be expected, after Wilde stepped into a life of ‘hideous darkness,’ that the world would ever hear from ‘one of its most perplexing and pathetic figures’ ever again.

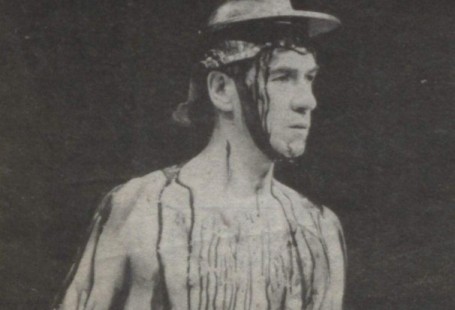

But the world did hear from him, as Wilde’s life was remembered, as his works were published posthumously, and as his plays began to be performed again. On 31 May 1907 Alex M. Thompson, writing for Labour publication Clarion, wrote a review of Wilde’s play A Woman of No Importance, which had been revived by its original producer Mr. Tree at His Majesty’s Theatre. Thompson stated that he found the play ‘vastly entertaining,’ detailing the brilliance of Wilde’s dialogue.

Meanwhile, the act of remembering Oscar Wilde continued. On 21 June 1909 the Dundee Evening Telegraph reported how a monument to the writer was set to be erected at the Père Lachaise cemetery, with the ‘execution of the monument [having] been entrusted to the Russian sculptor, Jacob Epstein.’ The Père Lachaise cemetery was set to Wilde’s final place of rest, as the Aberdeen Press and Journal detailed on 22 July 1909:

A telegram from Paris states that the body of Oscar Wilde was exhumed on Tuesday morning from the Bagneux Cemetery in the presence of Mr Ross, his executor, placed in a fresh coffin, and removed to the Père Lachaise Cemetery, where, after a religious ceremony in the chapel, it was laid in its final resting place.

‘Poet’s Tragic Destiny’

Some three years later the monument to Oscar Wilde went on show at the London studio of sculptor Jacob Epstein, as reported the Bournemouth Guardian on 8 June 1912. The newspaper described how the ‘poet’s tragic destiny’ was shown in the work, detailing how:

The conception embodied is that of a winged figure, in type recalling the Greek Sphinx, borne forward by the tragic Destiny implied in the character and genius of the dead writer. The eyes are closed, and above the head are little figures symbolising the characteristics of the motive will. The dominating plastic impression is that of breast and shoulder urged forward in defiance of all obstacles.

The Bournemouth Guardian lauds this ‘magnificent example of monumental sculpture,’ and the completion of the sculpture coincided with a renewed interest in the works of Oscar Wilde. Ralph Straus, writing for The Bystander in February 1912, describes how Wilde’s work ‘has come to be appreciated and enjoyed by many.’ Indeed, Straus reflects with fondness at how Wilde’s new popularity would have ‘amused him,’ with his works selling for a shilling at railway bookstalls.

But Wilde’s works were not just being enjoyed for a little light reading, Straus relating how:

Already, indeed, he has become the subject of innumerable essays and lectures. In France his name ranks high. In Germany he is a classic. His works have been translated into more than a dozen languages, and a bibliography of his works literally fills volumes. Yet he has been dead for no more than twelve years, and his tragedy is not yet altogether forgotten.

And yet Straus reminds us, that despite Wilde’s new popularity, the stain of his shame was not yet forgotten. This would be played out once more in Paris, as The Globe reported on in February 1913 under the headline ‘Ban on Oscar Wilde Monument.’ The newspaper detailed how:

When M. Epstein’s monument to Oscar Wild was placed in the Père Lachaise Cemetery there was an outcry in certain circles on the ground that some features of the monument might be offensive to French families.

The unveiling of the monument was postponed under orders from the Art Committee of the Prefecture of the Seine, who ultimately advised the Oscar Wilde Monument Committee ‘that if the monument is not modified within a fortnight it will be removed from the cemetery.’

Even in death, Wilde still faced both censure and censorship.

‘Echoes’ of Oscar Wilde

And just before the outbreak of the First World War, Wilde’s legacy of libel battles once more was thrown before the public. In April 1913 the Dundee Evening Telegraph reported how Lord Alfred Douglas had brought a libel action against Arthur Ransome for his book Oscar Wilde – A Critical Study, as well as against the Times Book Club, who distributed the book.

Douglas’s libel claim was tenuous; but it brought up once again the trial of Oscar Wilde, and all the prejudices he had been subjected to as his sexuality was revealed before the public. This caused the defence lawyer in the libel case, Mr. F.E. Smith, to pontificate how the ‘hideous revival of Wilde’s story when people were beginning to consider only his merits was due solely to Lord Alfred Douglas.’

Lord Alfred Douglas, Oscar Wilde’s lover, would make the headlines again when he appeared at the London Bankruptcy Court in June 1913. The Belfast Telegraph reported how at Douglas’s hearing he had claimed that the manuscript of De Profundis belonged to him, Wilde having addressed it to his former lover, although Douglas ‘had never attempted to get possession of it.’

Meanwhile the libel case lumbered on, the Dundee Evening Telegraph on 24 June 1913 dubbing it as an ‘Echo of [the] Oscar Wilde Case.’ Upon his case being dismissed, Lord Alfred Douglas petitioned for an appeal, but his appeal was ultimately dismissed. And then in November 1914 the same newspaper reported how Douglas was now on trial ‘on a charge of libelling Mr Ross,’ another of Wilde’s circle. The judge in the case condemned the characters of Ross, Douglas and Wilde, as he declared:

Both Mr Ross and Lord Alfred Douglas seemed to have fluttered round the possibly brilliant but certainly unwholesome person of Oscar Wilde as moths fluttered round a candle.

Indeed, at this time the reputation of Wilde could not overcome the prejudices he faced following his trial and conviction. The Globe on 30 December 1916, whilst reviewing Frank Harris’s account of Wilde’s life, dubbed the writer’s life as a ‘pitiful tragedy,’ and lauded Harris’s book for the portrait it painted of the author:

He leaves the impression that Oscar Wilde’s genius was largely composed of his colossal vanity and audacity, and that his nature had no fibre at all, as witness Mr. Harris’s description of his paralytic inability to seize the opportunity arranged by his friends of escaping from the imminent arrest he dreaded.

The Globe can excuse Wilde’s talents by tying them to his decadent personality, the personality which led him into ‘strange sins,’ as the Reading Observer dubbed his relationships with men. And not only was he vain, the Globe tells us, he was weak, his nature having ‘no fibre at all.’

And the Reading Observer on 8 June 1918 appeared to sum up how society felt at the time about mentions of Oscar Wilde, under the heading ‘Morbid Psychology:’

The late Oscar Wilde, whose name is periodically dragged before the public as though it was desired to vex his ghost, once observed sardonically that ‘to the pure all things are impure.’ If his troubled spirit has not yet found peace, he may still be reflecting on that paradox.

But as the 1920s approached, ushering with them a decade of change and sexual revolution, would attitudes to Wilde change?

Oscar Wilde ‘Still Writing’

There is a hint of things to come regarding Wilde’s reputation as the new decade dawned. In May 1922 the Pall Mall Gazette reported on how a librarian had nearly purchased letters purportedly written by Oscar Wilde, although it was later found that the ‘documents were not authentic.’ This was a token of Wilde’s posthumous fame: one, that the librarian thought letters by Wilde were worth buying, and two, that the forger thought that Wilde’s letters were worth faking.

Meanwhile, a startling revelation hit the press in July 1923 that new ‘Messages from Oscar Wilde‘ were being received from beyond the grave by Mrs. Travers Smith and her associate a Mr. V., via an Ouija board. The Aberdeen Press and Journal reported on these transmissions, which contained ‘many characteristic comments on living authors.’ Here is a selection of the commentary, which was purportedly from Oscar Wilde himself:

Arnold Bennett – His characters never say a cultured thing and never do an extraordinary one.

H.G. Wells – Time with ruthlessly prune Mr Wells’s fig trees.

Eden Philpotts – A writer has been very faithful, far too faithful, to his first love.

Bernard Shaw – The true type of the pleb. He is so anxious to prove himself honest and outspoken that he utters a great deal more than he is able to think.

John Galsworthy – He is my successor in a sense. He is the aristocrat of literature, the man who takes joy in selection, as our poor friend Shaw never did.

The messages were dismissed by literary experts, including by John Drinkwater, as being characteristic of a ‘man who had steeped himself deeply in Wilde’s plays and essays, and who had assimilated many of his mannerisms.’

But Mrs. Travers Smith was not to be daunted by such criticism, with the Shields Daily News reporting some months later in October 1923 how ‘Oscar Wilde [was] Still Writing.’ Indeed, Mrs. Travers Smith, of Chelsea, told the press how she and Mr. V. were ‘receiving by auto-scription, a new play from the spirit of Oscar Wilde.’ She claimed how ‘the first act of the play’ had already been ‘carefully dictated by the ghost of the dead dramatist.’

Change was in the air, and nowhere was this more apparent than at the locus of Oscar Wilde’s tragedy, Reading Gaol. In April 1924 the Belfast Telegraph reported how due to the ‘housing shortage’ in Reading, that the Town Council were now considering turning Wilde’s former place of incarceration ‘into flats.’

Meanwhile, the unlikely forces of Lord Alfred Douglas and Wilde biographer Frank Harris joined together in January 1926 to publish a new preface to Harris’s work on Wilde, as detailed the Aberdeen Press and Journal. Douglas had ‘objected to certain statements about himself contained’ in Harris’s book, but now ‘friends’ had brought the two together, and the new preface was published to condemn Robert Ross, one of Wilde’s confidantes:

The purpose of this ‘New Preface’ is to re-state Lord Alfred’s position as regards Wilde and the late Robert Ross, whom the joint authors combine to condemn as a most unsavoury and untrustworthy individual. It is asserted by him that Ross stole Douglas’s letters to Wilde and Wilde’s ‘De Profundis,’ which was a letter to Douglas, and that he further perpetually glorified his own and depreciated Lord Alfred’s part in Wilde’s last years.

Lord Alfred, it seemed, was more comfortable in claiming his role in Wilde’s life.

Oscar Wilde Revival

With the reputation of Oscar Wilde healing as the 1920s progressed, ‘amazing’ rumours surrounding the author and his ‘faked funeral’ reached the press. The rumour was outlined by the Dundee Evening Telegraph on 24 January 1927:

The amazing rumour, which has persisted for years, that Oscar Wilde did not die in 1900, but staged his ‘death’ to escape calumny, and has since been living the life of a recluse in a Paris suburb, has been scotched at last.

Wilde, it was said, induced a sculptor friend to make up a body to remember him. A doctor helped in the duplicity, and – so the story ran – the corpse of an unknown man was carried to Père Lachaise Cemetery, while the real Wilde went into discreet retirement.

The romance of such a rumour, whereby people even claimed to have seen Wilde in Paris, describing him as a ‘paunchy old man, grave and bearded,’ provided some comfort, that despite Wilde’s treatment in England, that somehow he survived. But the rumours were untrue, as the Dundee Evening Telegraph reported:

Dupoirier, the proprietor of the hotel in which Wilde died, has been traced, and denies absolutely the story of the fake funeral. ‘Wilde died in my arms,’ he states. ‘I have his false teeth as a memento.’

And by 1930, productions of Wilde’s were being performed without reference to his trial. In July 1930 the Graphic pictured ‘Scenes from an Oscar Wilde revival,’ with the caption:

Algy and Cecily, looing as ‘ninety-ish’ as their names in Mr. Michael Weight’s clever period costumes, in the new revival of ‘The Importance of Being Earnest,’ at the Lyric, Hammersmith.

Nowhere was it stated that this production was somehow tasteless, that Wilde’s ghost was be resurrected to conjure up once more some unsavoury moral horror. The Importance of Being Earnest was a play to be performed like any other, and Wilde was just another playwright.

But of course Wilde was not just any other playwright. The genius of his works elevated him beyond the norm, whilst he lived his life outside of the norm, ending up being persecuted for his sexuality.

In November 1930 the Mid-Lothian Journal marked thirty years since Wilde’s death, discussing the copyright questions surrounding his works. 10 percent royalties were now payable on the sale of his works, in what the Mid-Lothian Journal dubbed as an ‘important matter,’ for:

…there has been a revival of interest in Wilde lately, and booksellers tell me that they are selling more of his works now than they have done since before the War. There have recently been performances in London of ‘Lady Windermere’s Fan’ and ‘The Importance of Being Earnest.’

Oscar Wilde was revived, his works injected back into the mainstream, for public consumption once again. Memories of his trial had faded, and the genius of his works outweighed the prejudices surrounding his reputation. But at what cost? He had been dead for thirty years, derided and shamed throughout the last years of his life. For Wilde, it was too late, but we are privileged to be able to tell his story through the pages of our newspapers, and remember how he was persecuted as a queer individual, and celebrate how his works once again were enjoyed by thousands of people.

Register with us today and view three pages for FREE