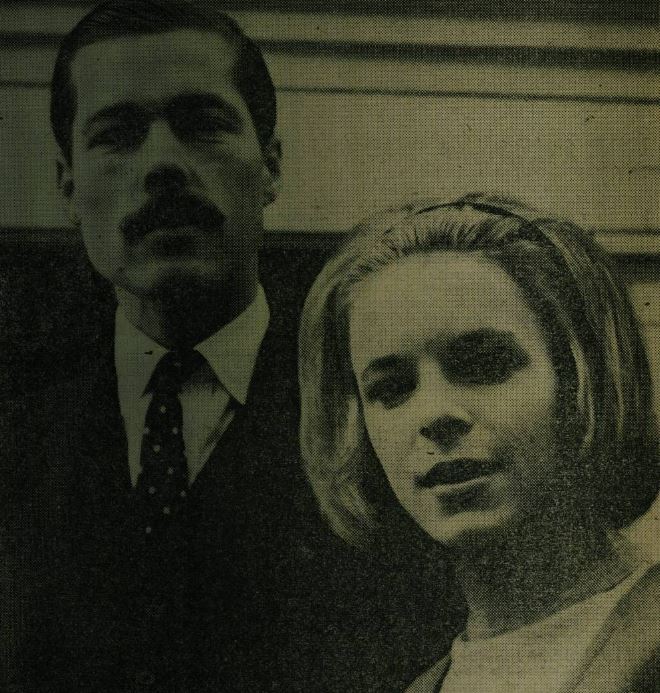

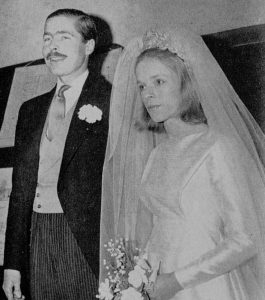

The disappearance of Richard John Bingham, 7th Earl of Lucan, following the murder of his children’s nanny Sandra Rivett and the attack of his wife Veronica, in November 1974, is one of the most notorious unsolved mysteries in British criminal history.

In this special blog, we will explore how his disappearance was reported on by the British press, using newspapers taken from our Archive. We will explore the newspaper reports from the days after the murder, whilst examining the press coverage in the decades following Lord Lucan’s disappearance, as the mystery became fodder for conspiracy theorists, scam artists, and armchair sleuths.

Register with us today and see what stories you can discover

Top tip: The Archive is home to a growing collection of late twentieth century titles, enabling you to research such stories as this one from decades like the 1970s.

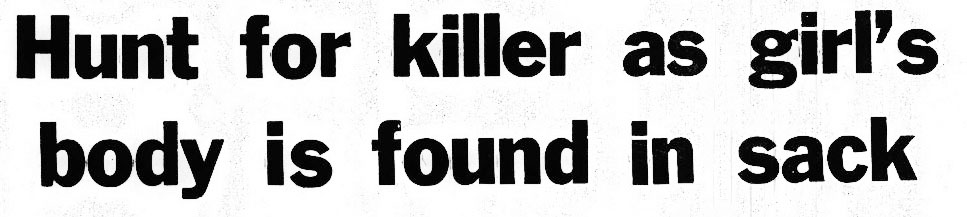

‘Hunt For Killer’

On 8 November 1974 the Aberdeen Evening Express reported how:

A nanny’s body has been found in a sack at the London home of Lady Veronica Lucan. It was discovered last night after Lady Lucan, who was suffering from head injuries, ran into the street shouting: ‘Murder.’

The article was unable to name the 29-year-old victim, who was later revealed to be the family’s nanny Sandra Rivett, as police were waiting for confirmation that her next of kin had been informed.

Immediately, Lady Lucan’s estranged husband, professional gambler Richard, came under suspicion, the Aberdeen Evening Express noting how police were ‘anxious to trace Lord Lucan, who has a home nearby.’

Meanwhile, witness statements were given to the press, a caretaker in a house nearby relating how ‘There was hell of commotion at about 11 o’clock last night. Police arrived in droves and one even had a dog.’

The alarm had been raised by Lady Lucan herself, as she ‘rushed to the nearby Plumbers’ Arms for assistance.’ The landlord of the pub, Derrick Whitehouse, relayed how:

She came staggering into the door. She was suffering from various head wounds – they were quite severe. She was covered in blood and was bleeding profusely. She was in a delirious state and kept saying, ‘I am dying, and my nanny has been killed.’ She kept saying, ‘my children, my children.’

Warrant Issued

Four days later on 12 November 1974 the Liverpool Echo reported how:

A warrant was issued to-day for the arrest of Lord Lucan following the death of his children’s nanny at Lady Lucan’s London home.

The warrant was issued to Detective Chief Superintendent Roy Ranson of Scotland Yard. The detective would remained tied to the case for decades to come.

The same report in the Liverpool Echo also revealed how the police were now ‘worried for the safety of Lord Lucan.’ A car, believed to have been used by the fugitive peer, had been found in Newhaven, a port town in East Sussex. Within the car, which was a Ford Corsair, blood had been found.

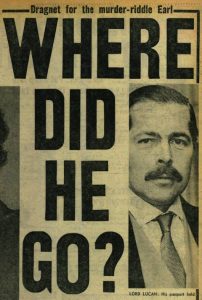

‘Where Did He Go?’

But despite the best efforts of the police, Lord Lucan had yet to be found. Tom Tullet, the Chief of the Daily Mirror’s Crime Bureau, penned an article on 12 November 1974 asking ‘Where Did He Go?,’ as Scotland Yard detectives remained ‘baffled’ by the disappearance of the peer.

As Lady Lucan recovered from her injuries at St. George’s Hospital, Hyde Park Corner, an armed guard at her bedside, ‘a dragnet [was] put out by police in Britain and France’ in an effort to find her alleged attacker.

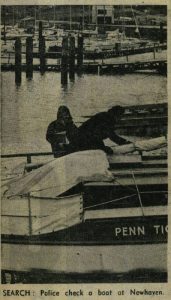

Tullet reported how police officers from both Sussex Police and Scotland Yard ‘searched nearly 1,000 small boats in Newhaven,’ the town where Lord Lucan’s car had been found. Hotels and boarding houses were also checked, but in vain.

The idea that Lord Lucan had crossed the English Channel to Dieppe was soon discounted as well, as ‘passengers were screened on both sides of the Channel.’

Meanwhile, further details were emerging about the attack on Lady Lucan and the murder of nanny Sandra Rivett. Tom Tullet for the Daily Mirror reported how it was the police’s belief that Lady Lucan was ‘attacked first and her screams brought nanny Sandra Rivett to her aid.’ Sandra was then ‘killed outright with a piece of lead piping.’

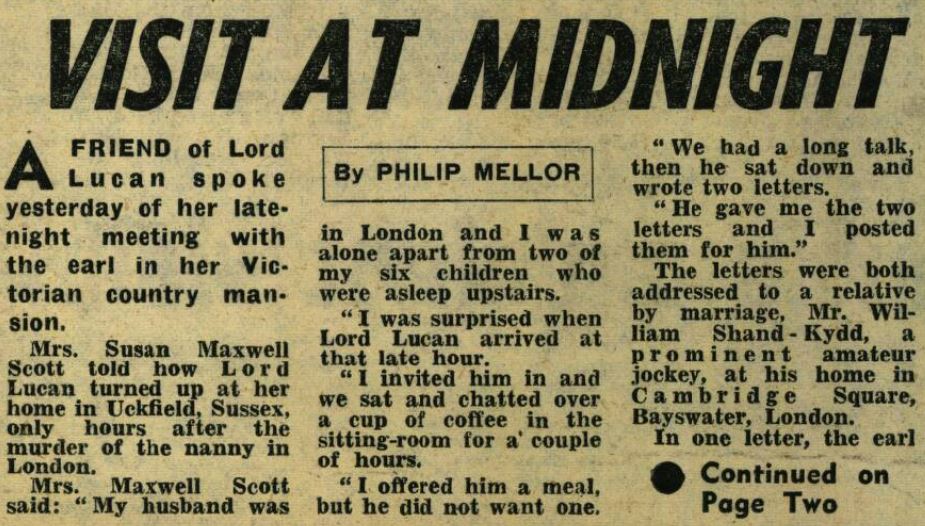

A ‘Visit At Midnight’

In the same edition of the Daily Mirror, on 12 November 1974, Philip Mellor reported on the extraordinary ‘Visit at Midnight’ that a friend of Lord Lucan had received from the peer on the night of the murder.

Susan Maxwell Scott told the police and press how ‘Lord Lucan turned up at her home in Uckfield, Sussex, only hours after the murder of the nanny in London.’

She gave the following account of the visit:

My husband was in London and I was alone apart from two of my six children who were asleep upstairs. I was surprised when Lord Lucan arrived at that late hour. I invited him in and we sat and chatted over a cup of coffee in the sitting-room for a couple of hours. I offered him a meal, but he did not want one. We had a long talk, then he sat down and wrote two letters. He gave me the two letters and I posted them for him.

The letters were addressed to William Shand-Kydd, a prominent jockey and a relative of Lord Lucan by marriage. In them, Lord Lucan actually stated that he had witnessed the attack on his wife at their home in Belgravia as he was driving past. One of the letters ended:

‘Look after the children, when they grow up, tell them the truth.’

Susan Maxwell Scott described how Lord Lucan left at about 1.30 am on the Friday morning. The next day, she heard the news about Lady Lucan, and promptly informed police of the strange visit.

Frogmen and Dogs

And as the days went by, the search continued for Lord Lucan. The Liverpool Echo on 14 November 1974 reported how ‘police frogmen and dogs were taking part in a big search of the Sussex coast,’ although their efforts were hampered by the poor weather, as ‘gales whipped up the sea and at times threatened to blow the searchers over the cliff tops.’

Boats moored at Newhaven continued to be searched, whilst sightings of the missing earl began to flood in, something that would occur in the decades following the crime, and cement the case into popular culture.

The Liverpool Echo relates how a woman had reportedly seen Lord Lucan on the Sunday, walking down some steps to the beach at Peacehaven, two miles from Newhaven. Meanwhile, Simon Dowling for the Daily Mirror on 15 November 1974 reported how ‘two trawlermen told detectives that they had seen the missing Earl at Newhaven.’

One of the men, Ernie Brown, said:

I was checking over my boat on Friday morning when I spotted this distinguished gentleman walking along the jetty. He had a moustache and later I recognised him from the photographs of Lord Lucan which appeared in the papers.

By the time the Aberdeen Evening Express appeared on the evening of 14 November 1974, the ‘search of the clifftop at Newhaven’ had been called off. Six tracker dogs had, furthermore, ‘combed the grassland and a nearby caravan sites without finding anything.’ Meanwhile, Newhaven’s clifftop Napoleonic fort had also been searched, but nothing was found.

On 15 November 1974 Simon Dowling for the Daily Mirror reported how the search had shifted to Newhaven harbour, where police frogmen were set to concentrate their search on a ‘death hole’ on the seabed. This so-called ‘death hole’ was known in the area for being ‘a spot where bodies can be trapped.’

‘My Duet With Lord Lucan’

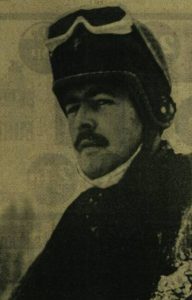

As police remained convinced of Lord Lucan’s guilt, others stepped forward to protest his innocence. One such person to do so was music teacher Caroline Hall, who had given Lord Lucan, who was known as ‘Lucky,’ thanks to his penchant for gambling, a piano lesson a day before the murder.

In an article entitled ‘My Duet With Lord Lucan,’ penned by Simon Dowling for the Daily Mirror, Caroline was quoted as saying:

We sat and chatted and played a duet. If he had been planning a murder, his hands would have betrayed him. You cannot disguise tension when you are playing the piano. But I noticed nothing unusual in him. He was perfectly calm and normal.

Lord Lucan was having the piano lesson in lieu of his daughter Lady Frances, who was then ten-years-old. Lady Frances had stopped taking the lessons, but her father had stepped in, so that ‘the lesson…would always be available for Frances should circumstances change.’

Caroline added how Lord Lucan:

…never once spoke violently about his wife or any of their nannies. To have committed this murder would have been to destroy everything: himself, his wife, and his children. I am deeply convinced he did not do it.

The Inquest

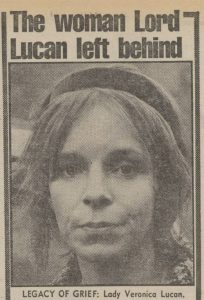

By the summer of 1975, Lord Lucan still had not been found. But the inquest into the murder of Sandra Rivett and the attack on Lady Lucan went ahead, with Lady Lucan bravely recounting the night of the attack. The inquest had been adjourned from December 1974, with Sandra Rivett’s body being released and subsequently cremated at Croydon Crematorium on 18 December 1974.

The Aberdeen Press and Journal on 17 June 1975 reported how Lady Lucan told the inquest that her ‘husband tried to strangle her on the night her children’s nanny was brutally murdered.’ She had been looking for Sandra Rivett before she was attacked ‘in the darkened kitchen basement of her Belgravia home,’ after the nanny had offered to make her a cup of tea, but had never appeared with it.

After Lady Lucan was attacked, Lord Lucan ‘took her upstairs and she lay down on the bed.’ When he went into the bathroom in search of something to wipe the blood off her face, Lady Lucan seized her opportunity to escape.

When asked ‘if she had any doubt it was her husband,’ the Aberdeen Press and Journal relates how Lady Lucan replied ‘No doubt at all.’

Also presented at the inquest were Lord Lucan’s letters, penned at the house of Susan Maxwell Scott. One of the letters ran as follows:

When I interrupted the fight at Lower Belgrave Street, and the man left, Veronica accused me of having hired him. I took her upstairs and…tried to clean her up…The circumstantial evidence against me is strong enough. Veronica will say it was all my fault…Veronica has demonstrated her hatred for me in the past and would do anything to see me accused.

Despite these claims from the missing peer, the inquest jury, which consisted of six men and three women, found Lord Lucan guilty of the murder of Sandra Rivett. It was the first time that a member of the House of Lords had been named a murderer since 1760, when Laurence Shirley, Fourth Earl Ferrers, was found guilty and hanged for the killing of his bailiff.

Lord Lucan ‘Alive and Well’

But still, there were those who persisted in the belief of Lord Lucan’s innocence, including the last person to have seen him alive, Susan Maxwell Scott.

The Aberdeen Press and Journal on 20 June 1975 reported how Susan Maxwell Scott had appeared on BBC television. In her interview, she told of how Lord Lucan ‘was obviously suffering from a certain amount of shock’ when he arrived at her Sussex home, but she maintained that he was ‘perfectly in control of himself.’

She added:

I’m convinced that he’s innocent. He was a very sweet, kind, considerate man who went out of his way to help people and to bother about them. I think that the probability is that he is alive.

Meanwhile, reported sightings of Lord Lucan continued to reach the pages of the press, and the police continued to investigate them.

On 28 June 1975 the Belfast Telegraph reported how the peer had allegedly been sighted at restaurant in St. Peter Port, Guernsey, but Guernsey police were ‘reasonably satisfied that Lord Lucan…[was] not on the island.’

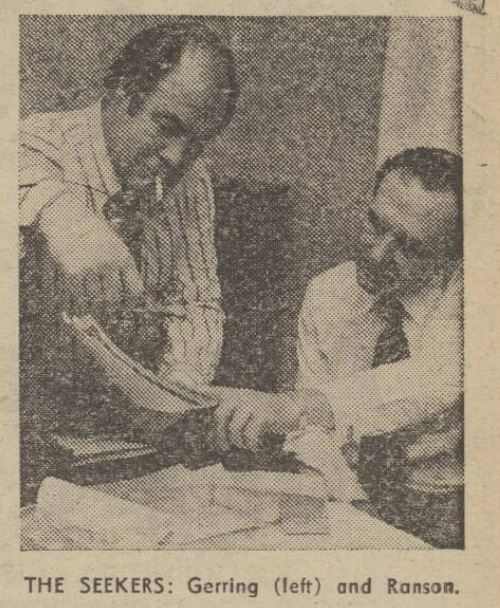

Lead investigator Detective Chief Superintendent Roy Ranson and his colleague Detective Inspector David Gerring had travelled to France, showing photographs of Lord Lucan to ’20 members of the staff of the Central Hotel in St. Malo.’ This lead was based on a tip from a Scottish holidaymaker, who claimed to have seen the missing man there earlier in June.

Ranson and Gerring were then set to travel to Cherbourg, to investigate claims from a hotelier that ‘a man resembling Lord Lucan stayed in her hotel several times this spring.’

The Bounty Hunter

By the early 1980s, extraordinary reports were emerging from the Caribbean that Lord Lucan had been found by ‘international bounty hunter John Miller,’ the man who had kidnapped Great Train robber Ronnie Biggs in 1981.

According to the Aberdeen Press and Journal on 11 September 1982, Miller, a 38-year-old former guardsman, had reportedly tracked Lord Lucan to South America. But suspicions had grown when Miller’s offers to take reporters to Caracas, Venezuela, where his men were reportedly ‘holding Lucan,’ were never followed through. According to one reporter, Miller ‘procrastinated and delayed’ when they said they would go to Caracas with him.

And soon, Miller himself had upped and left, leaving behind him a ‘trail of mystery and confusion.’ It was believed he had departed for Memphis, Tennessee, and soon his so-called discovery was widely disputed. Detective Chief Superintendent Roy Ranson was ‘unconvinced,’ stating how:

‘I feel sure if he was alive he would have been seen by now – I will believe it when I see it.’

However, John Miller’s mother Betty McKillop-Miller believed her son’s claims, telling reporters from her home in Motherwell:

‘It’s not too surprising, because when he kidnapped Ronald Biggs he said that Lord Lucan would be his next target.’

Lord Lucan ‘Alive, Depressed and Living in Canada’

And throughout the following decades, Lord Lucan still managed to captivate the press and public, as his disappearance moved into being something of an urban legend. Rumours of sightings persisted throughout the 1980s and 1990s, and when human remains were discovered, police were often forced into denying that they were those of the missing peer.

In March 1989 the Aberdeen Press and Journal reported that a skeleton had been found at Beachy Head, East Sussex, not far from Newhaven. The finding once again brought Lord Lucan’s name into the press, but a police spokesperson soon commented how there was ‘absolutely nothing to link this skeleton with Lord Lucan.’

The Aberdeen Press and Journal added how:

The age and sex of the skeleton is not yet known and police said that until tests are complete they will not know the cause of death or how long the body had been there. It was discovered by a member of the public in thick undergrowth on Saturday.

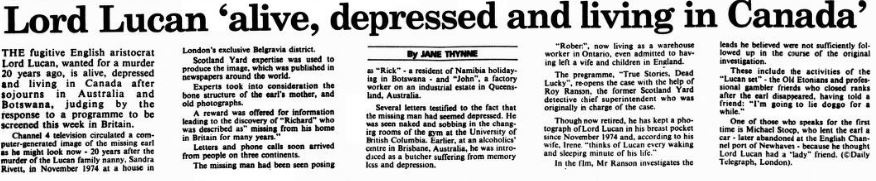

By the 1990s, the mystery of the disappearance of Lord Lucan remained cemented in the public consciousness through several television programmes. One such programme was aired by Channel 4 and was called ‘True Stories, Dead Lucky,’ in reference to the peer’s nickname, and it posited the bold claim that Lord Lucan was ‘alive, depressed, and living in Canada.’

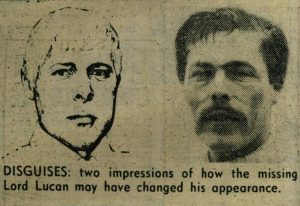

The television programme’s premise was based on the distribution of a ‘computer generated image of the missing earl as he might look now’ across the world. Lord Lucan’s name was left out, and instead the image was accompanied by the name ‘Richard,’ who was described as being ‘missing from his home in Britain for many years.’

Leads were soon collated from across three continents, the Irish Independent on 2 August 1994 reporting how ‘the missing man had been seen posing as ‘Rick’ – a resident of a Namibia holidaying in Botswana – and ‘John,’ a factory worker on an industrial estate in Queensland, Australia.’

Jane Thynne, writing for the Irish Independent, went on to describe how:

Several letters testified to the fact that the missing man had seemed depressed. He was seen naked and sobbing in the changing rooms of the gym at the University of British Columbia. Earlier, at an alcoholics’ centre in Brisbane, Australia, he was introduced as a butcher suffering from memory loss and depression.

Meanwhile, a man calling himself ‘Robert,’ who worked in a warehouse in Ontario, told acquaintances that he had ‘left a wife and children in England.’

Contributing to the programme was detective Roy Ranson, who was now retired. According to his wife, Roy had ‘kept a photograph of Lord Lucan in his breast pocket since November 1974,’ and he thought ‘of Lucan every waking and sleeping minute in his life.’ Ranson believed that were some leads that were not properly followed up in the original investigation, including ‘the activities of the ‘Lucan set’ – the Old Etonians and professional gambler friends who closed ranks after the earl disappeared.’

Also contributing to the Channel 4 documentary was Michael Stoop, the man who had lent Lord Lucan the car that was then abandoned in Newhaven. This was the first time that Stoop had spoken publicly, and he stated that he had let Lucan borrow the car because he thought he ‘had a lady friend.’

‘Spilling The Beans’

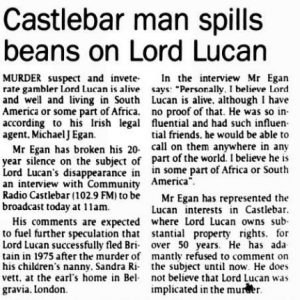

Despite these sightings from across the world, Lord Lucan was still not found. But rumours continued to persist, as one Irishman ‘broke his 20-year silence’ to ‘spill the beans’ on Lord Lucan’s disappearance.

The man, Lord Lucan’s Irish legal agent, Michael J. Egan, was from Castlebar, which had been historically tied to the Lucan family since the 1500s. Lucan owned the ground rents in the County Mayo town, which residents refused to pay until the peer reappeared.

As reported in the Sunday Tribune on 10 September 1995, Egan told local radio station Community Radio Castlebar how:

Personally, I believe Lord Lucan is alive, although I have no proof of that. He was so influential and had such influential friends, he would be able to call on them in any part of the world. I believe he is in some part of Africa or South America.

Furthermore, Egan, who had represented ‘the Lucan interests in Castlebar’ for upwards of fifty years, believed that Lord Lucan was not guilty of the murder.

And as the new millennium rolled around, speculation around Lord Lucan’s whereabouts continued fill newspaper columns. In September 2003 Matthew Grey for the Irish Independent reviewed newly published book Dead Lucky, in which author and Scotland Yard Duncan MacLaughlin claimed that Lord Lucan had ‘drank himself to death in Goa.’

MacLaughlin’s claims centred around a ‘bearded hippie,’ who was nicknamed ‘Jungle Barry’ and had arrived ‘on foot in Bombay in 1975.’ This man, whose full name was Barry Halpin, was known as an ‘eccentric Irishman who was uncomfortable talking about his past.’ Halpin lived in Goa, making a ‘meagre living playing backgammon and leading jungle trips for Western tourists,’ before passing away in 1996.

Indeed, Halpin had even once claimed to be Lord Lucan. The proprietor of his local bar, Pradip Lawande, saw a British visitor with a newspaper clipping of the missing earl. He remarked to Halpin how it looked like him, and Halpin nodded, saying ‘That’s right. I’m Lord Lucan.’ Lawande owned that he ‘never knew whether he was serious or joking.’

But Matthew Beard for the Irish Independent remarks in his review how the book would ‘struggle to win over sceptics in the absence of a body or DNA evidence.’ Halpin, an alcoholic, had died from ‘cirrhosis of the liver and a few other things.’ He had been cremated in ‘a Viking-style funeral’ pyre, which had been doused ‘with his favourite Goan tipple, feni,’ his ashes scattered at a nearby waterfall.

Lord Lucan’s wife was not convinced by the claims either; Beard described how she thought the book’s theory was ‘nonsense.’ Meanwhile, Beard again shared the opinion of Lucan’s former best friend, John Aspinall, who had said in 2000 that ‘the earl’s bones probably lay ‘250 feet under the Channel.’’

Lord Lucan was not declared officially dead until 2016, when his son George inherited the title. Sightings of him still continue to be reported, with one emerging from Australia as recently as 2020. And although the mystery endures to this day, it is important to remember Sandra Rivett, whose life was so savagely ended that day. A young woman, with her life ahead of her, is often forgotten with all the rumours that continue to swirl around the case. Indeed, press coverage of the time makes Sandra nothing but a victim, but she was much more than that, much more than a player in the theatrics of Lord Lucan’s mysterious disappearance.