The theft of the Mona Lisa in 1911 is one of the art world’s most sensational crimes. The Leonardo da Vinci masterpiece was taken, almost in plain sight, from its place in the Louvre, Paris, with very few clues as to the identity of its thief left behind.

In this special blog, we will tell the story of the theft of the Mona Lisa through our newspapers, as the crime filled newspaper columns across the world. We will draw on our global collection of titles, from Britain, Ireland, Canada and even Malta to tell the remarkable story of one of the most extraordinary art heists in history.

Register now and explore the Archive

The Mona Lisa is missing

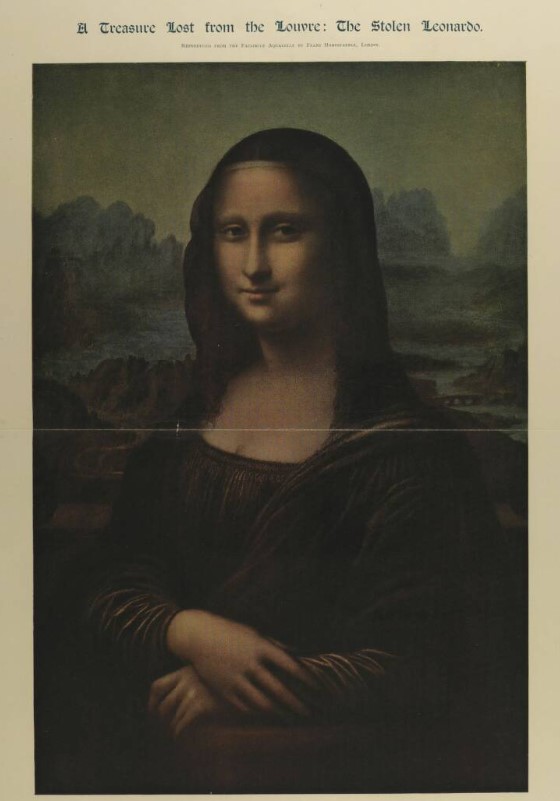

On 27 August 1911 London publication Lloyd’s Weekly Newspaper reported how the Mona Lisa, ‘one of the most famous pictures in the world, and Leonardo da Vinci’s masterpiece, vanished from the Louvre on Monday, and not a trace of its whereabouts has been found.’

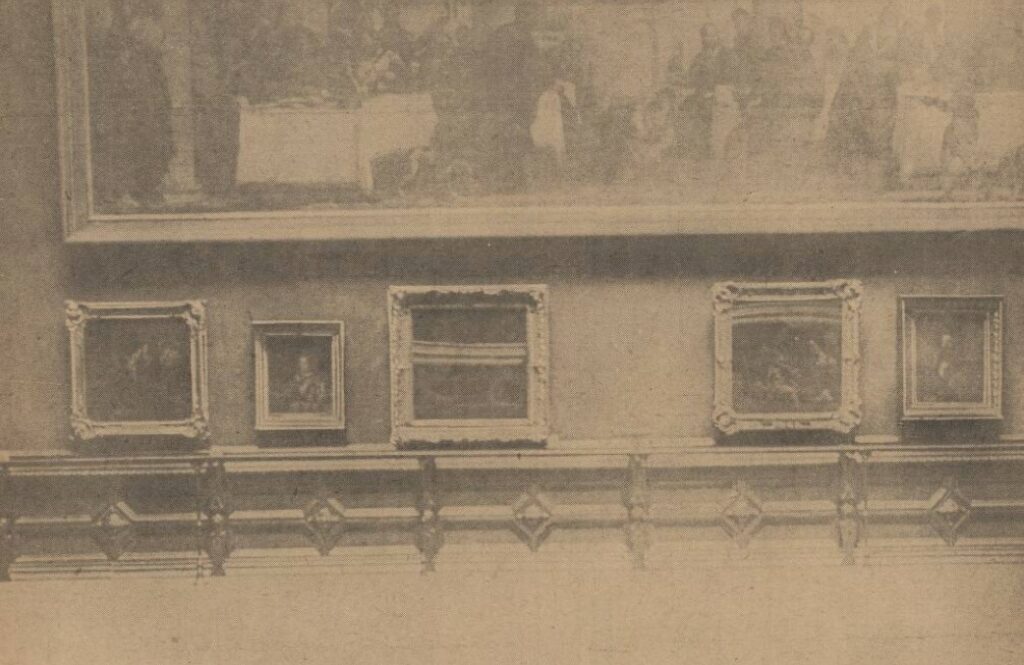

The Mona Lisa had been stolen from the Louvre museum on 21 August 1911, throwing Paris ‘into a ferment of excitement.’ Despite ‘every inch of the Louvre [having] been searched without success,’ few clues as to its whereabouts had been found, save for the ‘the frame and protecting glass,’ which ‘were found hidden away in a dark corner.’

Lloyd’s Weekly Newspaper provided an outline for its readers of how the theft of the Mona Lisa was uncovered:

The police have practically fixed the hour of the theft at between 7 and 8.15 on Monday morning. M. Picquet, a master mason, was summoned to execute some repairs in the main building on that morning. He has been working at the Louvre for many years, and knows its contents as well as many an art connoisseur. At 7 a.m. on Monday he had occasion, with two companions, to pass through the celebrated Salon Carré. He called his companions’ attention to the Joconde, and said to them, ‘Do you see that picture hanging there? It is the most valuable painting in the whole world, and is worth millions.’

Exactly an hour and a quarter later, as the newspaper tells us, Monsieur Picquet returned through the Salon Carré and looked for the Mona Lisa, ‘but, to his astonishment, it was no longer there.’

Mondays at the Louvre were when all the keepers received a day off. The museum, according to Lloyd’s Weekly Newspaper, was closed to the public, and ‘its immense halls and valuable treasures are left to the care of about a dozen watchmen, instead of about eighty attendants.’ Artists and photographers, however, were permitted to visit.

As soon as the theft of the painting was noticed, however, authorities at the museum swung into action, with ‘every keeper, sub-keeper, or deputy-assistant-keeper of the Louvre in Paris [being] summoned to a council of war.’ The Prefect of the Police ensured that the Louvre was cleared and its gates shut and locked, with ‘every nook and cranny of the historical building’ being searched. But to no avail.

Early Rumours

Almost as soon as the theft of the Mona Lisa was made public, rumours began to swirl about what had happened to the painting.

Lloyd’s Weekly Newspaper reported how early interest was centred on Bordeaux, and indeed, Canadian newspaper the Ottawa Free Press on 26 August 1911 reported from Paris how ‘there appears to be no doubt here that Leonardo Da Vinci’s famous painting Mona Lisa, was taken to Bordeaux, whence it is feared it will be carried either to Spain or South America.’

According to the Ottawa Free Press, a witness had seen a ‘stout man, carrying a large panel covered with a horse blanket, take the 7.47 express for Bordeaux on Monday morning,’ soon after the Mona Lisa was presumed to have been taken.

Indeed, Lloyd’s Weekly Newspaper reported that two men had been arrested near Bordeaux ‘on suspicion of being concerned in the theft.’ They were 27-year-old student Erhardt Elrick, and tailor Emil Koster. They had been seen depositing a package, which ‘may’ have contained the missing picture, at ‘small railway station near Bordeaux.’ Elrick and Koster were arrested on the Friday, four days after the theft of the Mona Lisa, but no case was established against them.

Meanwhile, police detectives in Paris were ‘searching for a man in a blouse.’ This man was believed to be an artist, and had been ‘seen by a workman at a spot where the frame of the lost pictured was discovered.’ At the same time, in Bordeaux, as the Ottawa Free Press relates, police had searched a steamer named Cordillera, which was bound for South America, but ‘there was no trace of Mona Lisa on board the vessel.’

‘One of the Direst Disasters in the World of Art’

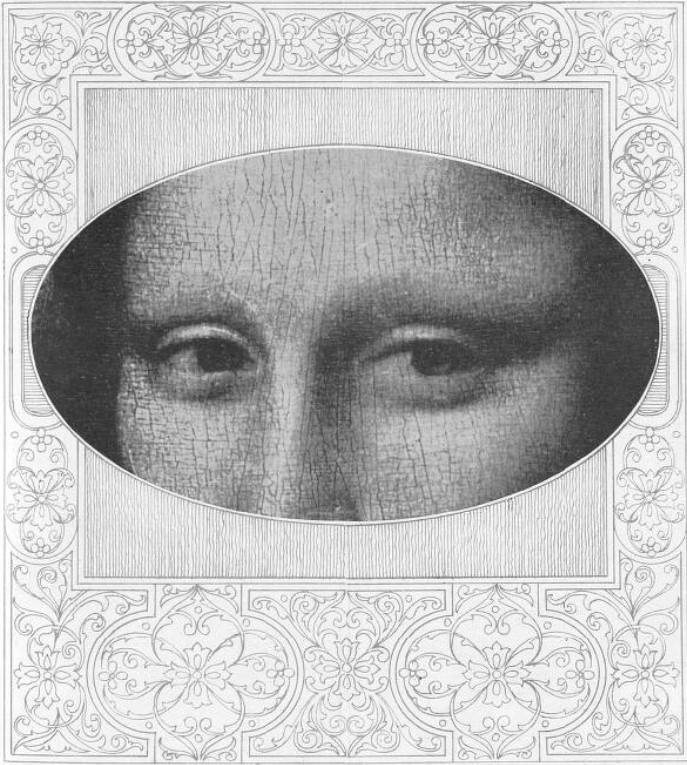

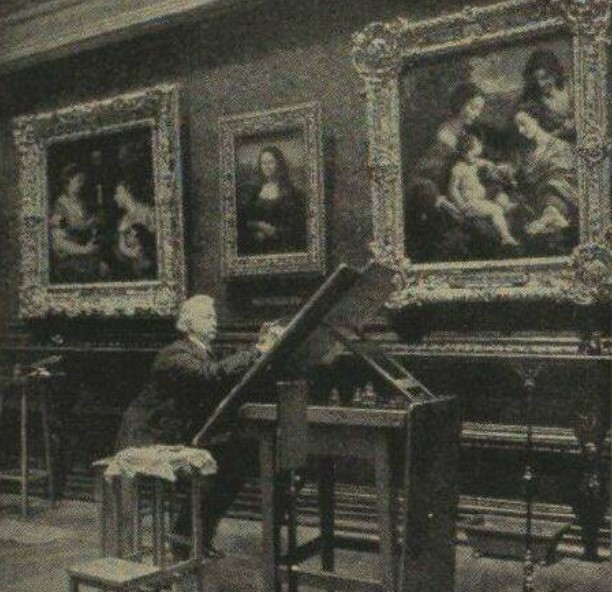

In the week following the theft of the Mona Lisa, people around the world reacted with shock that the great Leonardo da Vinci masterpiece could have been taken. British national newspaper the Daily Mirror on 29 August 1911 pictured the ‘vacant space in the Louvre where the lost Mona Lisa hung,’ whilst the next day pictorial paper the The Sketch speculated whether the ‘fascinating eyes’ of the painting had inspired a ‘devoted admirer…to carry her off.’

The matter, however, was ‘really too serious for joking,’ The Sketch reflected, as ‘the loss of Leonardo’s masterpiece would be one of the direst disasters that could happen in the world of art.’

People were also asking just how one of the world’s most valuable pieces of art could just be taken in such a manner. A correspondent calling themselves ‘Art Lover’ wrote the following piece to the editor of the Westminster Gazette, which was published by the paper on 26 August 1911:

It is curious that the authorities of the Louvre should have been so lax in guarding Leonardo’s great picture, considering the many warning they have had during the last few years, and the well-known thefts from the same building. I must have seen the insecurity of the portrait of the Mona Lisa referred to quite a dozen times during the last few years, both in English and foreign publications, and yet the French people themselves seem to have turned a deaf ear to the warnings.

Indeed, Lloyd’s Weekly Newspaper also outlined the painting’s vulnerability to theft:

Although unquestionably the most valuable work in the Louvre collection, it was not held by a padlock or any special fastenings. It was hung with an ordinary wire cord, which rest on four brass headed nails. A cool and expert thief would have been able, by lifting it from underneath, to unhook it and walk off with it inside half a minute.

On 1 September 1911 London’s Daily News reported that the Director of the French National Museums and the Keeper of the Louvre had been ‘dismissed’ as a consequence of the theft of the Mona Lisa. With no sign still of the masterpiece, rumours as to what had happened to it continued to swirl across the globe.

New York, Berlin and Madrid

The theft of the Mona Lisa flushed all sorts of intrigue out into the open. The Daily News on 1 September 1911 reported how a gentleman in Paris ‘made a regular practice of helping himself to small but quite select trifles at the Louvre.’ In story that hit the pages of the press across the globe, this thief preferred to steal Phoenician statuettes, ‘not apparently on aesthetic grounds, but because they are a handy size for an overcoat pocket.’

The gentleman pincher of Phoenician statues only ‘troubled the Louvre…when he was really hard up.’ He expressed his ‘outrage’ at the ‘conduct of the thief of the Mona Lisa; at once by his audacity and by his spoiling a profitable occupation by drawing attention to it in so dramatically insistent a fashion.’

Meanwhile, fingers of suspicion were pointed at figures across the world. Our Maltese newspaper the Daily Malta Chronicle and Garrison Gazette on 1 September 1911 printed a report from Berlin that a ‘rich American art dealer who is now crossing over to New York from Europe is suspected of the theft of the Mona Lisa.’ Authorities in New York were poised for his arrival.

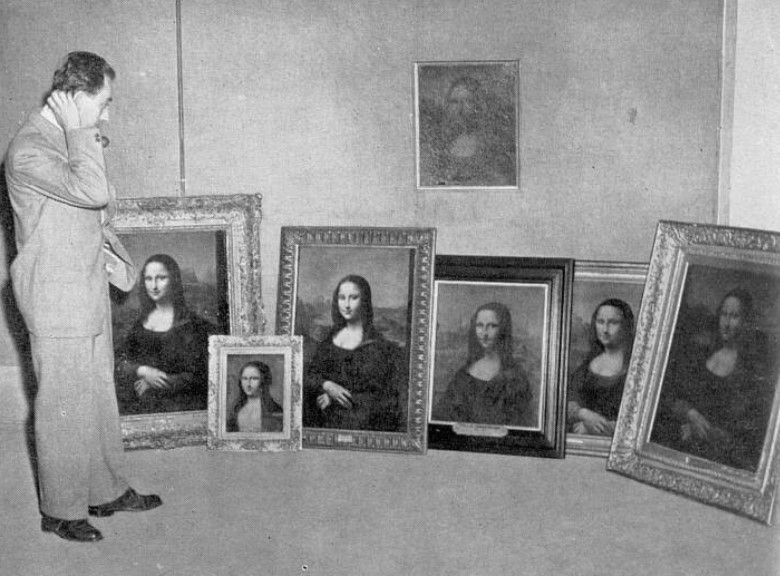

A week later the Ottawa Free Press reported from Madrid that ‘two foreigners have been arrested at Leon.’ They had been carrying a basket which contained a Mona Lisa, which they said ‘was only a copy of Leonardo da Vinci’s stolen masterpiece, which they were taking to Colomera, where they reside.’ No further details had been released by authorities.

A week after that British regional paper the Leicester Evening Mail reported how ‘the search of the Paris police for Mona Lisa has extended as far as Berlin.’ The police apparently had been tipped off by a letter received from a man in Breslau (Wrocław, Poland), ‘who stated that he had been asked to find a purchaser for a mysterious picture of great value.’

French police, according to the Leicester Evening Mail, arranged a rendezvous at a hotel in Berlin. But the Breslau informant did not turn up, and it was discovered that he was a ‘convicted imposter.’ The Mona Lisa was still missing.

‘Mona Lisa Lost But Entertaining’

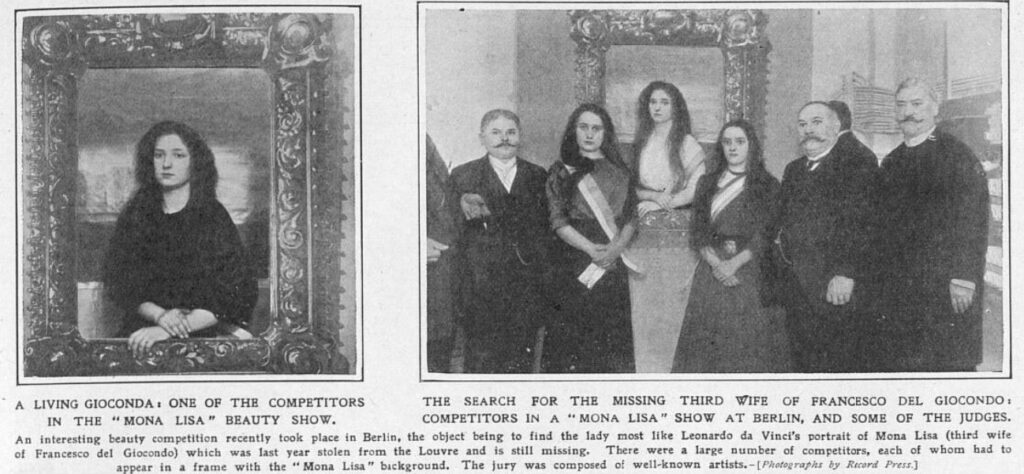

And although the great piece of art was missing, the theft of the Mona Lisa had really taken root in the popular imagination, and continued to entertain.

One of our cinema industry publications the Kinematograph Weekly on 28 September 1911 included in its list of current releases ‘The Disappearance of the Mona Lisa – An Unusual Comedy.’ The theft of the painting had made the crossover into one of the newest types of media: the cinema.

Meanwhile, three months after the theft in December 1911 the Ottawa Free Press reported how the Mona Lisa was ‘lost but entertaining,’ as ‘the now celebrated theft of the Mona Lisa has inspired a new and interesting version of tableaux vivants.’ The Canadian newspaper described how:

Such an affair given in New York a few days ago was heralded by posters announcing that the Mona Lisa had been discovered in a certain parish hall, and inviting ‘all those interested in art’ to come and view her for the modest price of 10 cents a head. The tableaux were arranged with great cleverness, the rising of the curtain suggesting a little play, and the scenes being the Salon Carré (or square room) of the Louvre Museum, whence the great painting was abstracted. In the half light of the stage a thief was seen to lift the picture from its frame, pack it among other canvasses on his arm and disappear.

Back in Paris, on 7 October 1911, the Louvre was reopened, without its most famous treasure. The Ottawa Free Press described the ‘extraordinary scenes’ at the French museum:

The building was better guarded than ever it had been before. Many women among the sightseers brought bouquets of flowers, chiefly red or white roses tied with white ribbons. Soon after the re-opening of the galleries some excitement was caused by a wild-looking woman who said she was the Mona Lisa come back and wanted to be restored to her frame.

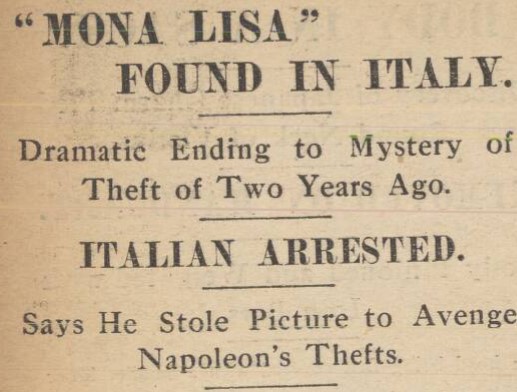

The Mona Lisa is Found

After two long years, on 13 December 1913 Dublin-based paper the Evening Irish Times reported how Leonardo da Vinci’s ‘immortal picture’ had finally been found, although it admitted that the ‘story of its recovery is disappointingly simple.’ The piece related how:

A man, who admitted that he had stolen it from the Louvre, offered it for sale to a picture dealer in Florence; he was arrested, and the picture is now in the hands of the police. The only explanation which the thief could put forward was that he wanted to revenge himself upon France for the depredations of Napoleon in Italy.

This man was Vincenzo Peruggia (1881-1925), an Italian museum worker and artist, who had lived in Paris and had worked at the Louvre. The Nottingham Evening Post on 17 December 1913 reported how Peruggia had stolen the Mona Lisa ‘alone, and without accomplices, and had alone kept it during the two years it was in his possession.’

For most of the time that the Mona Lisa had been missing, the painting had been secreted in Peruggia’s Parisian apartment. The masterpiece, despite widespread speculation, had not left France. Peruggia, however, about two years after the theft, had returned to his native Italy, and had come out of hiding to offer the painting for sale.

Meanwhile, steps were put in place to return the artwork to France, Scottish national newspaper the Scotsman reporting from Rome on 18 December 1913 how ‘Signor Credaro, Minister of Education, has informed the French Ambassador that he hopes to be able to hand over the ‘Mona Lisa’ to his keeping on Saturday afternoon.’ Furthermore, the next day the Aberdeen Press and Journal was reporting how the Mona Lisa was set to be exhibited in Rome, with an opportunity to view the piece ‘for one or two days at Milan.’

‘Like A Royal Visit’

Italian authorities were treated with great acclaim by the French government following the discovery of the Mona Lisa. The Westminster Gazette on 20 December 1913 reported how:

…the Keeper of the National Museums will leave for Rome to-morrow, taking with him a number of decorations of the Legion of Honour intended for Italian authorities and other persons who helped to recover the missing ‘Guiconda,’ especially Professors Ricci and Poggi. Signor Geri, the collector to whom Peruggia brought the ‘Gioconda’ from Paris, will receive the Rosette of Public Information and a reward of £1,000 from the Committee of the Society of the Friends of the Louvre.

Indeed, the newspaper stated that upon the Mona Lisa’s return to Paris, the painting would be exhibited at the Ecole des Beaux Arts, with the admission fee going towards ‘Italian charitable institutions.’

The Mona Lisa, then, was on the move. Canadian newspaper the Hamilton Daily Times on 22 December 1913 described her trip through Italy as ‘like a royal visit,’ reporting from Rome how:

The journey of the ‘Mona Lisa’ from Florence to this city was like the progress of the Czar of Russia on a visit to a foreign country. Troops guarded every foot of the railroad, and a strong force of detectives were on the train bearing the masterpiece. Their eyes never left the box in which Da Vinci’s painting reposed.

The painting was then ‘handed over for safe keeping to’ Signor Credaro, the Italian Minister of Education. It was placed in his office, ‘where only King Victor Immanuel and a few privileged persons who were permitted to see it.’ Next, the Mona Lisa was ‘formally handed over to M. Carrere, the French Ambassador.’

The Dundee Courier, reporting on 23 December 1913, dubbed this exchange as the ‘Mona Lisa Romance’ between the two European nations. Signor Credaro, during the handover, had expressed his ‘hope that the picture would form another link in the friendly relations existing between France and Italy.’ In response, French ambassador Monsieur Barrere ‘expressed his happiness in accepting the picture and his thanks in the name of the whole French people for the exquisite courtesy shown by the Italian nation in the affair.’

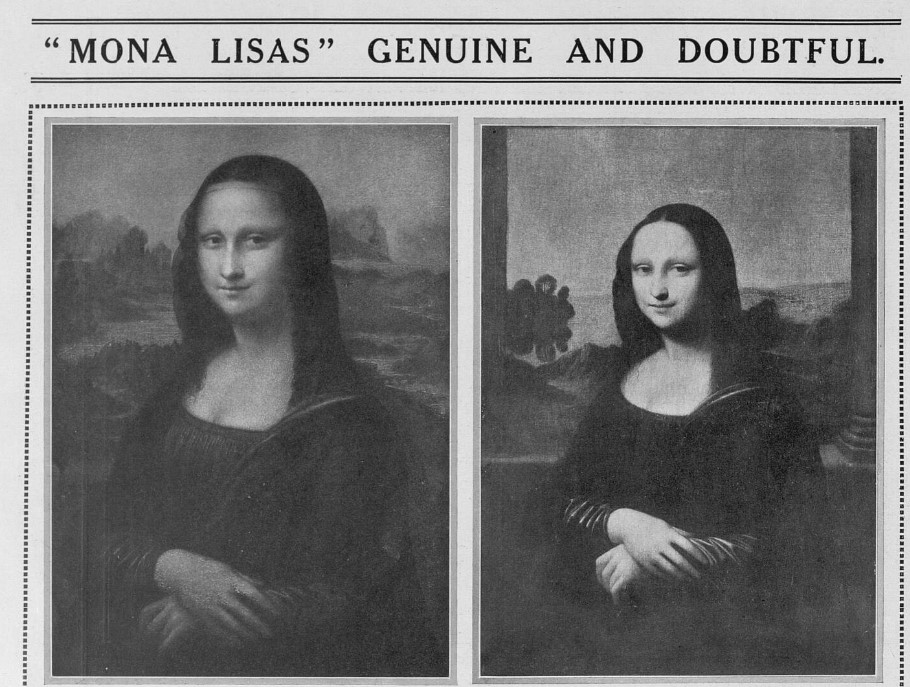

All that now had to be done was for the Mona Lisa to be ‘formally identified.’ This identification was carried out by Monsieur Leprieur, the Director of the Art Galleries at the Louvre, who confirmed the provenance of the painting ‘by means of documents brought from Paris.’

As for the thief, Vincenzo Peruggia, he was treated leniently by Italian authorities. His patriotic motives were hailed, and he was sentenced to be imprisoned for one year and fifteen days. However, he was released after just seven months, and served in the First World War, in which he was held as a prisoner of war for several years. He then returned to France, and died on 8 October 1925, his 44th birthday.

Find out more about art history, sensational crimes from the past and much more besides in the pages of our newspaper Archive today.