American-born jazz age superstar Adelaide Hall (1901-1993) was a Black music legend, who from 1938 onwards made Britain her home. She went on to have a long and successful career in the UK.

In this very special blog, as part of Black History Month on The Archive, we will celebrate this jazz age queen who came to Britain and entertained thousands of people via her stage and radio performances, using newspapers taken from our Archive.

A Star Is Born

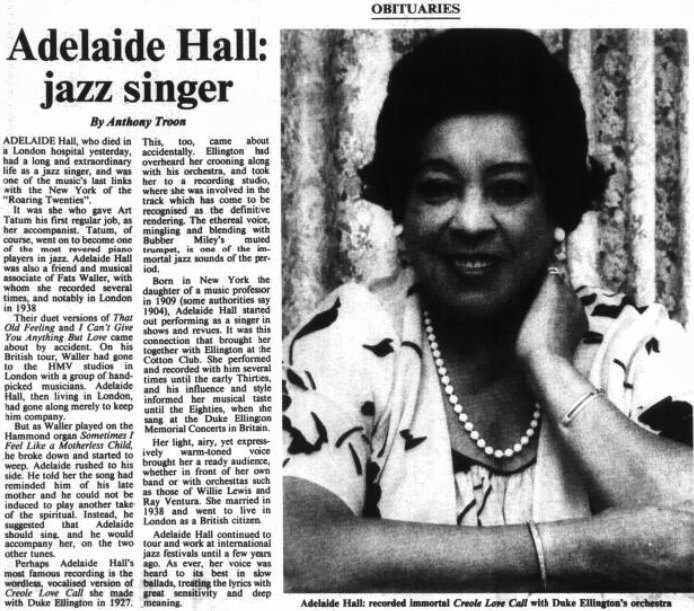

To go back to the beginning of Adelaide Hall’s remarkable life, we’re going to the end of it. Upon her death in November 1993 our newspapers marked her passing, printing obituaries that took a look at her long life.

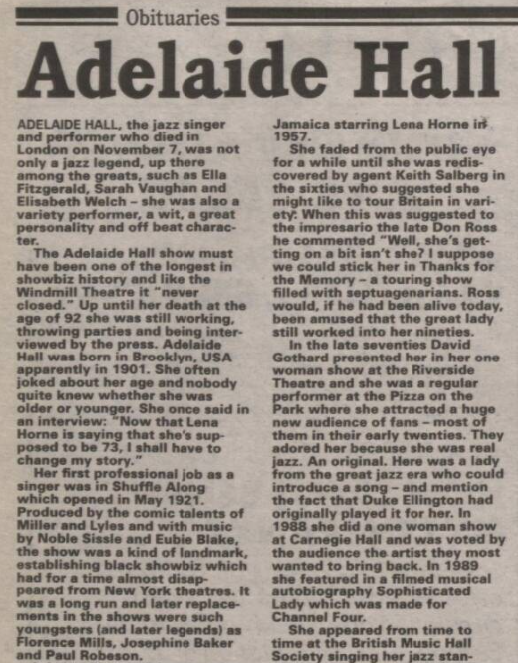

One newspaper to print such an obituary was The Scotsman, which informed its readers how the jazz star was ‘born in New York the daughter of a music professor in 1909 (some authorities say 1904).’ Special entertainment title The Stage put Adelaide’s birth year at 1901, however. This misdirection over her age was just part of Adelaide Hall’s act, however, The Stage revealing how she ‘often joked about her age and nobody quite knew if she was older or younger.’ Indeed, she was once quoted as saying ‘Now that Lena Horne is saying that she’s supposed to be 73, I shall have to change my story.’

Adelaide Hall would first take to the stage in 1921, appearing as a singer in Shuffle Along in New York. The Stage explains how the ‘show was a kind of landmark, establishing Black showbiz which had for a time almost disappeared from New York theatres.’ It was destined for a long run, with legends like Josephine Baker and Paul Robeson later joining the cast.

Creole Love Call

The same Stage obituary then describes how Adelaide Hall made her first European tour in 1926. After this, in 1927, she appeared on Broadway.

It was in 1927 that she perhaps made her ‘most famous recoding,’ alongside jazz legend Duke Ellington – a piece named ‘Creole Love Call.’ The Scotsman on 8 November 1993 looks back at this landmark musical moment:

This…came about accidentally. Ellington had overheard her crooning along with his orchestra, and took her to a recording studio, where she was involved in the track which has come to be recognised as the definitive rendering. The ethereal voice, mingling and blending with Bubber Miley’s muted trumpet, is one of the immortal jazz sounds of the period.

She would go on to record more with Duke Ellington, performing at the Cotton Club, before, as The Stage explains, she moved to Europe in 1934. Having made her debut in 1931 at the London Palladium, the singer initially made Paris her home, opening the La Grosse Pomme nightclub there.

But as The Scotsman relates, Britain was to be the place she made home. With her Trinidadian husband Bertram Hicks, Adelaide Hall moved to London as a British citizen in 1938, the same year that she made an appearance at Drury Lane’s Theatre Royal. Whilst in London in 1938 she also recorded with another American jazz legend, Fats Waller, the pair duetting on ‘That Old Feeling’ and ‘I Can’t Give You Anything But Love.’

Adelaide Hall Takes The UK By Storm

It’s from 1939 that we start to see more and more mentions of Adelaide Hall in our newspapers, as she had made the UK her home. She appeared in shows across the country, as well as on the radio.

For example, on 18 May 1939 the Shields Daily News previews the appearance of Adelaide Hall, the ‘celebrated…singer from the Cotton Club,’ in the next day’s ‘late night dance music’ session. Readers of the Coventry Evening Telegraph, meanwhile, were told that it was ‘dancing time,’ heralding the appearance of Joe Loss and his ‘full radio band,’ alongside Adelaide Hall.

She also made live appearances, the Surrey Advertiser showcasing a ‘great holiday bill‘ at the Kingston Empire, with Adelaide Hall being the highlight of the programme.

Adelaide Hall was fast achieving celebrity status. Indeed, she was featured in an ‘After The Theatre‘ anecdote by Stanley Parker for the Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News in June 1940. Parker recounted how, after a ‘terrific ‘Jam’ Session at Cambridge,’ he was walking along the Backs with Adelaide Hall, when the pair became sentimental, the singer apparently stating: ‘it makes you feel like you’d like to get away from all this night life…and become an undergraduate.’

Parker was relieved, however, that Adelaide Hall was still ‘on the job,’ as he put it, continuing to bring ‘down the house’ with her energetic performances.

Wartime Contribution

With the outbreak of the Second World War, Adelaide Hall’s life would be changed, whilst she would go on to make an important contribution to the war effort.

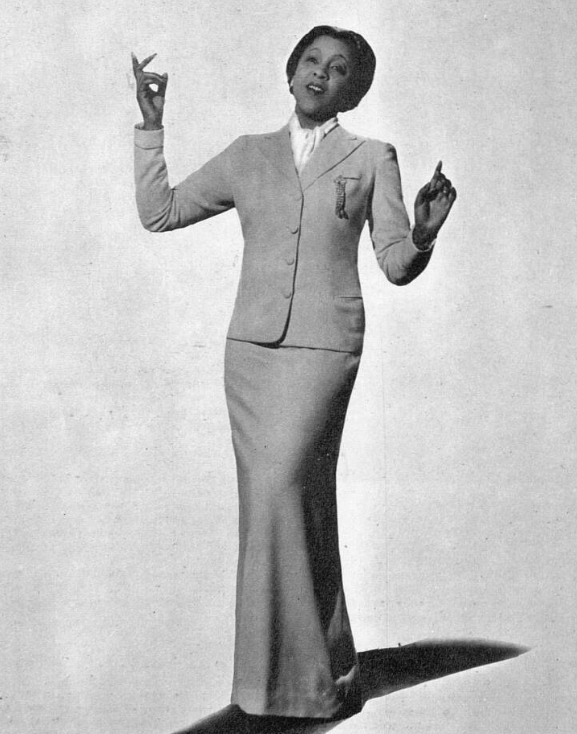

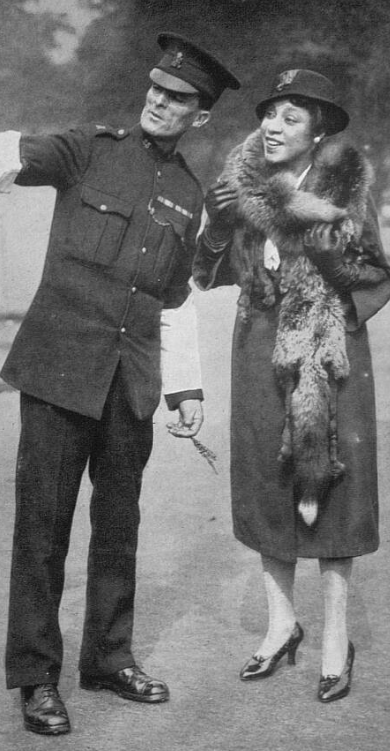

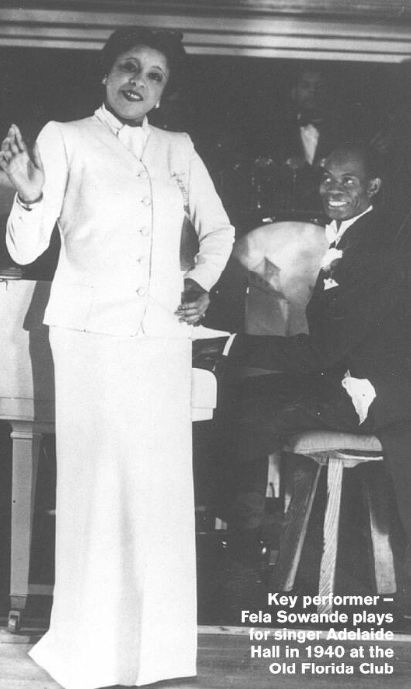

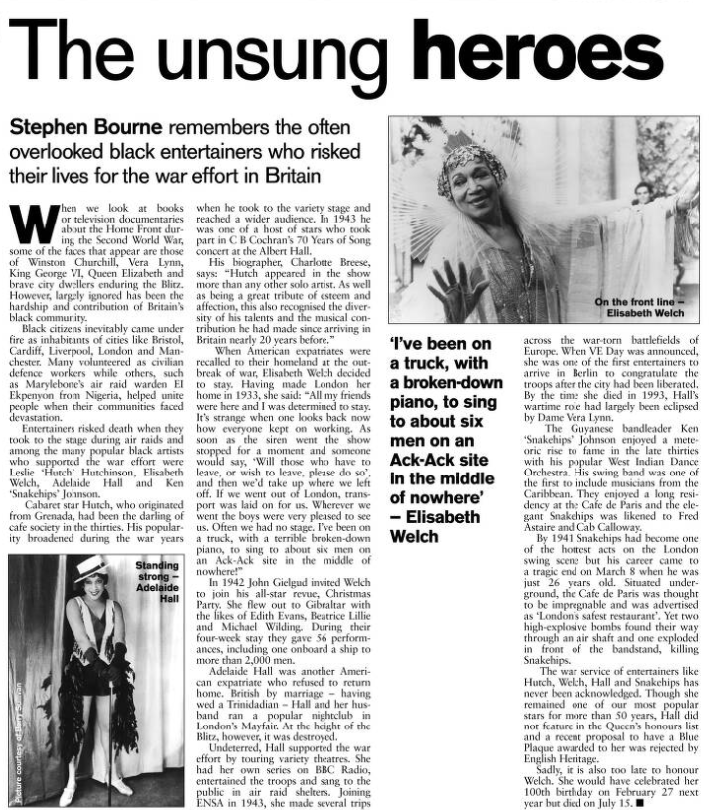

In a powerful piece for The Stage in August 2003, Stephen Bourne profiles ‘the often overlooked Black entertainers who risked their lives for the war effort in Britain.’ As well as highlighting those Black citizens who ‘came under fire as inhabitants of cities like Bristol, Cardiff, Liverpool, London and Manchester,’ and those who volunteered as civilian defence volunteers and air raid wardens, like Nigerian El Ekpenyon, Bourne celebrates the ‘popular Black artists who supported the war effort.’ These performers included Leslie ‘Hutch’ Hutchinson, Elisabeth Welch, Ken ‘Snakehips’ Johnson, and Adelaide Hall.

Bourne explains how ‘entertainers risked death when they took to the stage during air raids,’ recounting how Adelaide Hall’s Mayfair club, which she ran with her husband, was destroyed ‘at the height of the Blitz.’ Despite being an American expatriate, Adelaide ‘refused to return home,’ instead supporting ‘the war effort by touring variety theatres,’ keeping morale high as she did so.

During the Second World War, as Bourne explains, Adelaide had her own series on BBC Radio. She joined the Entertainments National Service Association (ENSA) in 1943, and with ENSA ‘she made several trips across the war-torn battlefields of Europe.’ Indeed, when VE Day was announced, she was in Berlin, and she became ‘one of the first entertainers to congratulate the troops after the city had been liberated.’

Sadly, however, as Bourne notes, ‘by the time she died in 1993, Hall’s wartime role had largely been eclipsed by Dame Vera Lynn.’

Topping The Bill

After the war ended, Adelaide Hall’s popularity in Britain continued. The Aberdeen Press and Journal in February 1946 describes her top of the bill performance at the city’s Tivoli Theatre, where she put ‘over with vivacious informality some of the numbers she sang to our troops in Germany.’ The piece relates how ‘her rendering of some of the more sentimental numbers has a fascination of its own,’ and she received ‘a great ovation’ on this her first ever visit to Aberdeen.

Her tour of the UK continued, with the Croydon Times previewing the visit of ‘the famous Adelaide Hall’ to the Croydon Empire in 1946.

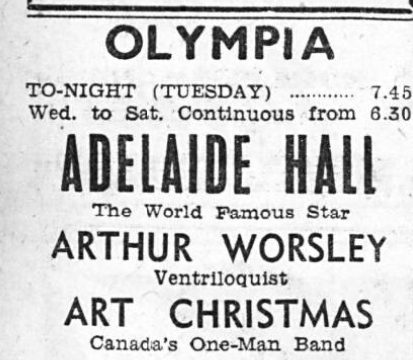

Adelaide Hall continued to perform regularly throughout the latter half of the 1940s, Dublin’s Evening Herald highlighting a ‘bright spot’ at the Dublin Olympia in September 1949, which was of course Adelaide Hall. The newspaper described how she was ‘was deservedly and repeatedly encored last night for her selection of songs, ranging from Calypso numbers to Blues and even to the latest tune about the beauties of Killarney.’ Indeed, the same newspaper advertised her as the ‘world famous star.’

Hall’s star was in ascendance, and it is truly remarkable how many performances she appeared in at this time. The Holloway Press in 1950 describes her ‘surprise’ appearance at a concert at Islington’s Bentham Court Community Centre, where her ‘magnetic personality held the audience entranced when she gave a half-hours non-stop performance.’

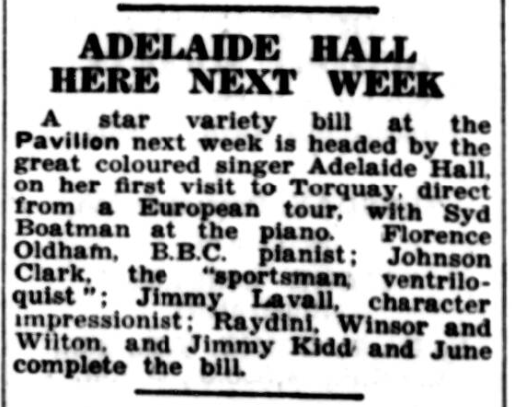

December 1950 marked the singer’s first visit to Torquay, meanwhile, where the Torquay Times, and South Devon Advertiser looked forward expectantly to a ‘star variety bill at the Pavilion…headed by the great…singer Adelaide Hall.’

In And Out of Retirement

The Stage’s 1993 obituary then recounts how Adelaide Hall went on to appear in Kiss Me Kate in 1951 and Love Me Judy in 1952, starring alongside Lena Horne on Broadway in 1957.

However, as the Illustrated London News explains, ‘when her husband died in 1963, she retreated into semi-retirement,’ The Stage going one further by outlining how ‘she faded from the public eye for a while until she was rediscovered by agent Keith Salberg in the sixties who suggested she might like to tour Britain in variety.’

Adelaide may have been gone for a little while, but by 1971 she was back. Roy Whitehead, writing for the Coventry Evening Telegraph in April 1971, pointed out the longevity of the star’s career, penning how ‘Adelaide Hall has been a first-class cabaret artist for some 40 years, and most of them have been spent in this country.’

Whitehead was reviewing Adelaide’s new LP, which was recorded by Columbia in London in 1969, entitled ‘Hall of Fame.’ He concludes his review by stating:

Throughout the 10 titles the band equip themselves excellently, and Adelaide Hall’s professionalism and expertise shines through. This disc will have limited appeal, but just listen to a couple of tracks before passing it up. It has much to commend it.

57 Years Later…

Adelaide Hall may have been advancing in age, but the passing of the years would not prevent her from performing. The Stage describes how:

In the late seventies David Gothard presented her in her one woman show at the Riverside Theatre and she was a regular performer at the Pizza in the Park where she attracted a huge new audience of fans – most of them in their early twenties. They adored her because she was real jazz. An original. Here was a lady from the great jazz era who could introduce a song – and mention the fact that Duke Ellington had originally played it for her.

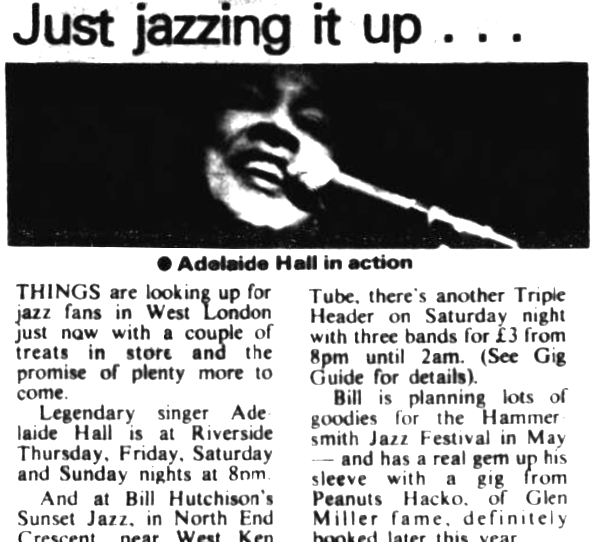

The Hammersmith & Shepherds Bush Gazette in March 1981, sixty years after her singing debut, describes how things were ‘looking up for jazz fans in West London’ with the appearance of ‘legendary singer’ Adelaide Hall at the Riverside.

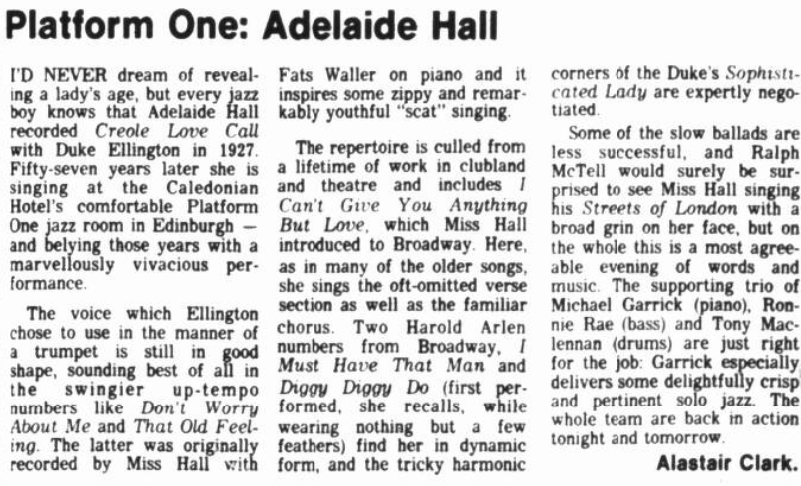

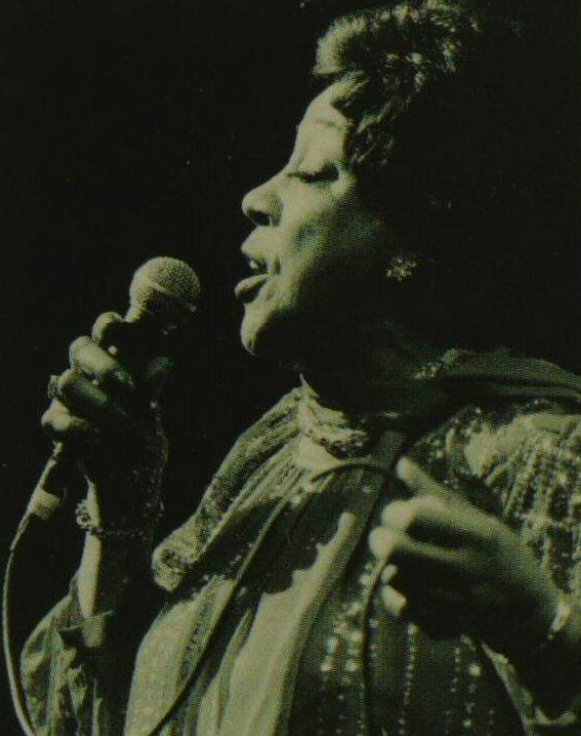

Meanwhile, Alastair Clark for The Scotsman in June 1984 reviews Hall’s performance at Edinburgh’s Platform One jazz room, 57 years after she had recorded ‘Creole Love Call’ with Duke Ellington. He wrote how:

The voice which Ellington chose to use in the manner of a trumpet is still in good shape, sounding best of all in the swingier up-tempo numbers like ‘Don’t Worry About Me’ and ‘That Old Feeling.’ The latter was originally recorded by Miss Hall with Fats Waller on piano and it inspires some zippy and remarkably youthful ‘scat’ singing.

Clark’s review continues:

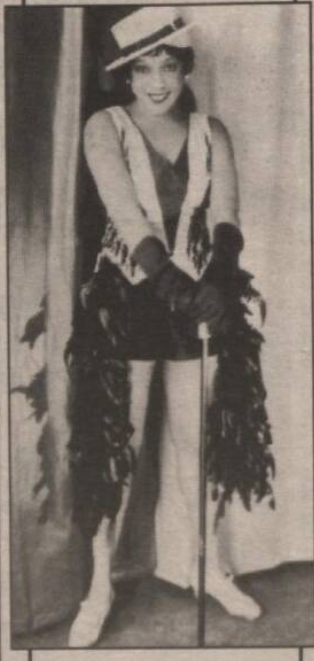

The repertoire is culled from a lifetime of work in clubland and theatre and includes ‘I Can’t Give You Anything But Love,’ which Miss Hall introduced to Broadway. Here, as in many of the older songs, she sings the oft-omitted verse section as well as the familiar chorus. Two Harold Arlen numbers from Broadway, ‘I Must Have That Man’ and ‘Diggy Diggy Do’ (first performed, she recalls, while wearing nothing but a few feathers) find her in dynamic form, and the tricky harmonic corners of the Duke’s ‘Sophisticated Lady’ are expertly negotiated.

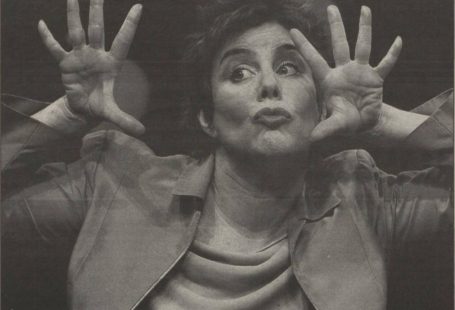

‘Addie Sings’

In 1987 Adelaide took to the stage once again, this time in the Duke Ellington Anniversary Concert, which was held on 29 April 1987, on what would have been Ellington’s 88th birthday. In a piece entitled ‘Addie Sings‘ for the Illustrated London News, Peter Clayton describes how the music for the concert would be performed by the Midnite Follies Orchestra. The orchestra’s co-leaders, saxophonist Alan Cohen and pianist/trombonist Keith Nichols, were impressive with their recreation of the music of the 1920s and 1930s, but the real genuine article from the jazz age was Adelaide Hall.

Clayton relates how:

There will be one performer who will not have to act a musical part or imagine what it was like to entertain in Harlem, Paris and London in pre-war years: Adelaide Hall. The concert will be almost a double anniversary, for this October 60 years will have passed since Addie made a classic record of ‘Creole Love Call’ with Ellington.

Clayton also describes an encounter with Adelaide Hall after her ‘demurely modest comeback’ in 1970. Having spotted her name on a poster for Lewisham Town hall, he took his tape recorder to go and visit her:

I went to tea with her in a little flat off the Cromwell Road. As far as I was concerned, Adelaide Hall was star. But there were many stairs and there was no lift. So she did a wonderfully un-starlike thing: she opened a window five floors up and flung something out which landed near my feet. It was a paper bag, with her keys in it.

The Death of A Star

After performances at Carnegie Hall, and a star turn in Channel Four autobiography Sophisticated Lady, the theatrical tour de force that was Adelaide Hall passed away. She died at a London hospital on 7 November 1993, Anthony Troon for The Scotsman remembering her ‘long and extraordinary life as a jazz singer,’ and her position as one of ‘music’s last links with the New York of the ‘Roaring Twenties.’’

Furthermore, Patrick Newley for The Stage described her as ‘a wit, a great personality and off beat character,’ penning how:

The Adelaide Hall show must have been one of the longest in showbiz history and like the Windmill Theatre it ‘never closed.’ Up until her death at the age of 92 she was still working, throwing parties and being interviewed by the press.

Newley compiled industry recollections of Adelaide, including this recollection from the Chairman of the British Music Hall Society Jack Seaton:

She was an amazing character – and a bit of a handful. She always wanted to be picked up in a car and would pile mountains of dresses into the back. You couldn’t move in the car for all her clothes. Then she would start eating chocolate biscuits while telling you about Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington and Count Basie. You had the entire history of jazz from her with the biscuit crumbs on the floor. Then when you’d get out of the car – she’d ask you to take all her costumes up to her flat – which was about six floors up. She did it to everybody – but we all loved her. Biscuits and all.

Meanwhile, agent Keith Salberg was quoted as saying:

She was one of the greatest performers I have ever seen. It was a privilege to work with her. She was unique in that she could play anywhere. She was a jazz legend – but she was just as happy performing in variety or in a play or musical. I can truthfully say that when she walked on a stage – she simply lit up the whole theatre. Very few people can do that.

The world had lost a true legend.

Adelaide Hall Remembered

A year after Adelaide Hall’s passing, the entertainment world came together to mark the incredible life of the singer. The Stage on 6 October 1994 reported how:

Adelaide Hall will be remembered in the West End later this month, when friends and colleagues from the entertainment world stage a charity gala in her memory. Besides remembering her life, the performers will be hoping to raise money for a number of children’s charities and the Imperial Cancer Research Fund.

Adelaide Hall was a true legend of her time, a queen of the jazz age, who brought her talent to British audiences, contributing to the war effort and entertaining and delighting audiences for seventy years.

Find out more about Adelaide Hall, the jazz age, and much more besides, in the pages of our newspaper Archive today.