In 1872 farm labourers in Warwickshire went on strike, in a movement that academic and statesmen Henry Fawcett dubbed to be the ‘most important that as ever taken place among our labourers.’ Echoing such movements in Britain’s industrial towns and cities, this radical rural action would lead to the formation of the National Agricultural Labourers’ Union.

In this special blog, using newspapers from the time, we will examine this ground-breaking agricultural action. We will look at how the National Agricultural Labourers’ Union came to be founded, the reaction of farmers to both the strike and the labourers’ unionisation, as well as discovering how the movement spread and gained support from important contemporary figures.

Register now and explore the Archive

‘A Fair Day’s Wage For a Fair Day’s Work’

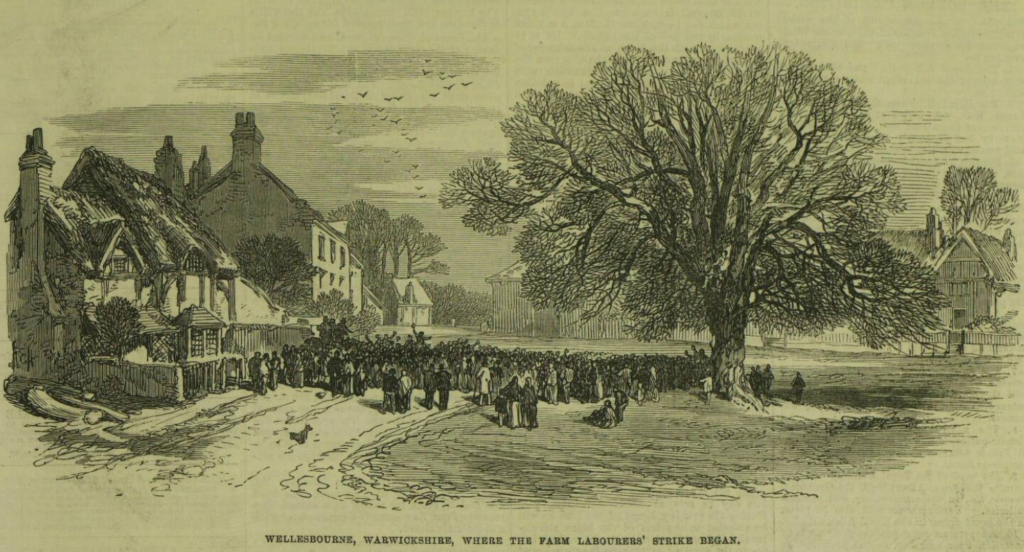

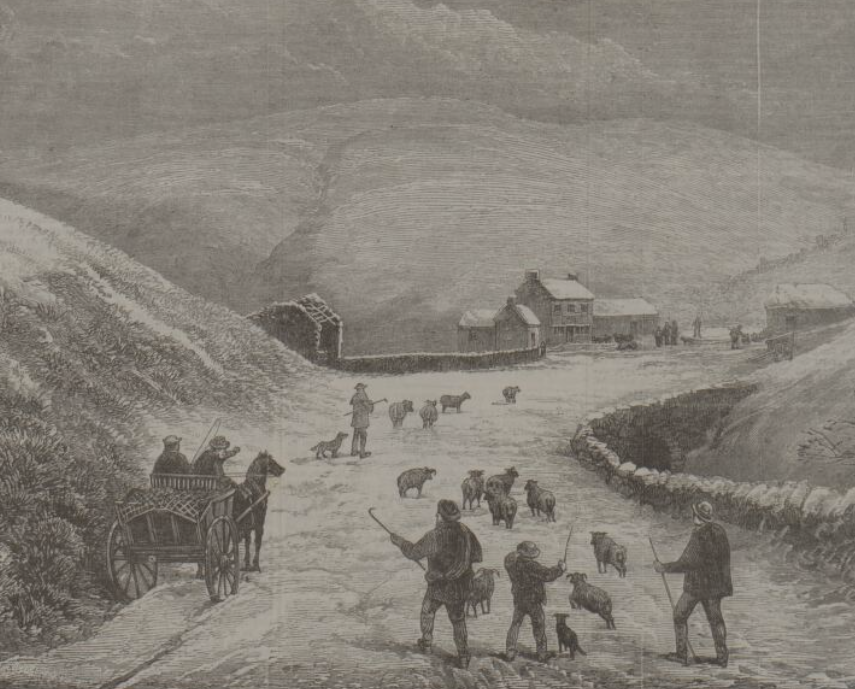

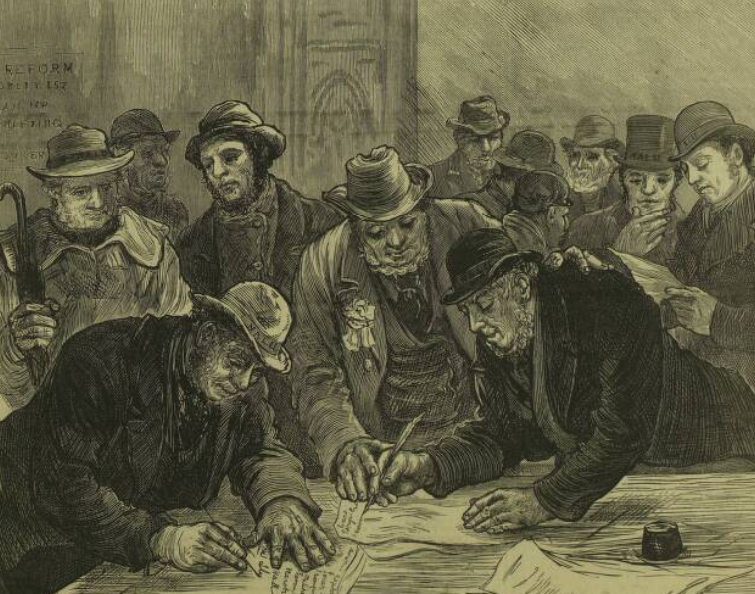

On 27 April 1872 popular pictorial publication the Illustrated London News printed a picture of a gathering under a chestnut tree in the village of Wellesbourne, Warwickshire.

The Illustrated London News describes the drawing as follows:

Our Illustration this week is a view of the scene in the village of Wellesbourne, at the gathering of the rustic assembly under a well-known chestnut-tree, where Lewis and Arch and the other leaders of this movement have repeatedly spoken to hundreds of these poor men, insisting on their right to ‘a fair day’s wage for a fair day’s work.’

This ‘agitation’ among farm labourers in South Warwickshire ‘had been going on some time,’ the piece explains, leading to the creation of a ‘Trade Union for the purpose of enforcing their demand for higher wages.’

But what was behind this agitation, which precipitated the formation of a trailblazing agricultural trade union?

The Warwickshire Labourers’ Union

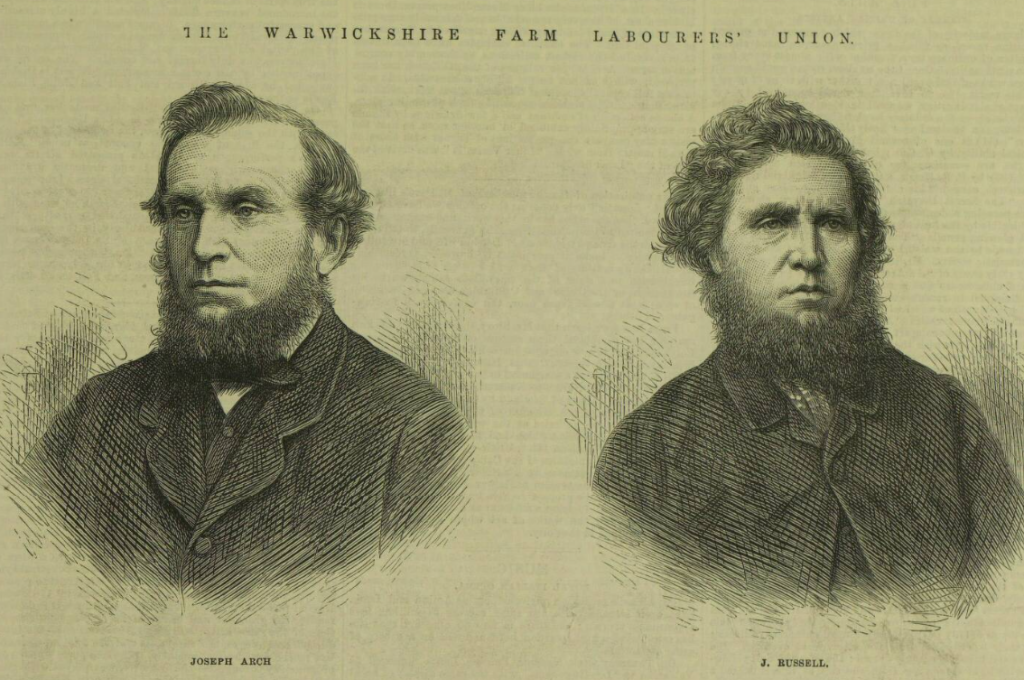

The village of Wellesbourne was where it all began in February 1872. Here, in what was intended to be only a small meeting, 2,000 people came to hear Methodist preacher and labourer Joseph Arch (1826-1919) speak. Inspired, this meeting sparked strike action among farm labourers in Warwickshire, and by the end of March 1872, the Daily News was reporting how ‘there are indications that this strike will not terminate just at present.’

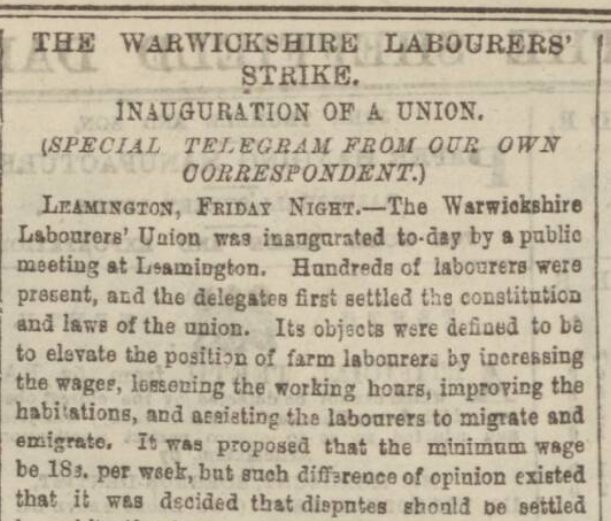

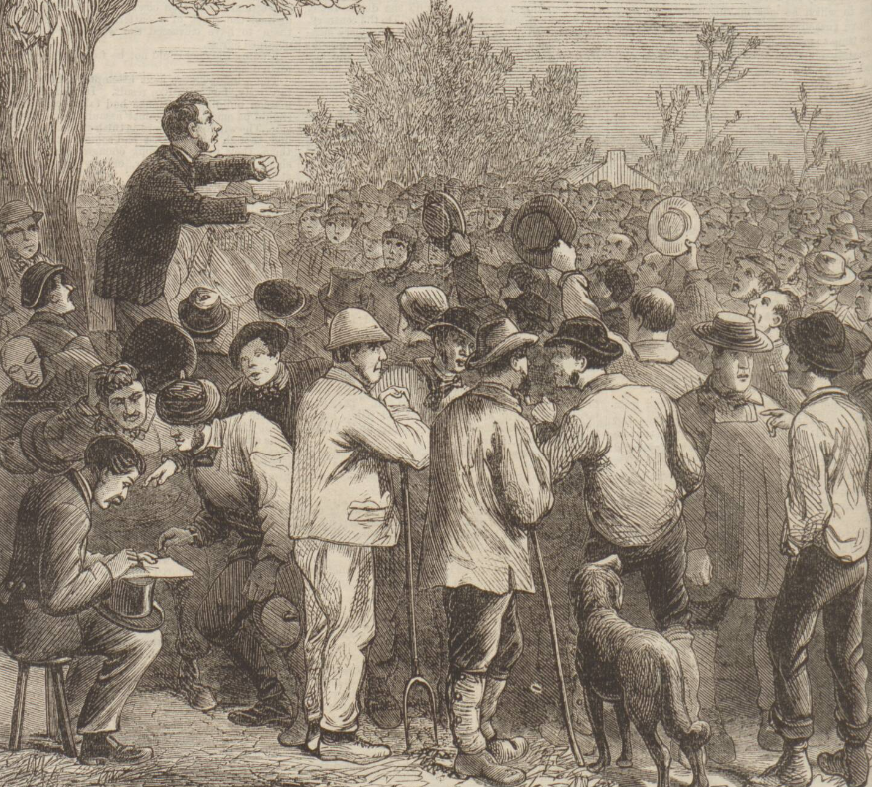

Indeed, the strike had led to the creation of a new Warwickshire Labourers’ Union, which was inaugurated, according to the Sheffield Daily Telegraph, on 29 March 1872 at a ‘public meeting in Leamington.’ The Sheffield newspaper describes how ‘hundreds of labourers’ were in attendance, where ‘the delegates…settled the constitution and laws’ of the new union.

The Sheffield Daily Telegraph outlines the conversations that were had at the meeting:

It was proposed that the minimum wage be 18s per week, but such difference of opinion existed that it was decided that disputes should be settled by arbitration between the directors of the union and the employers.

The piece continued:

A proposition that the hours be a day’s work, overtime fourpence the hour, and all Sunday work overtime, with certain exceptions, gave rise to an animated discussion… A proposal that the entrance fee should be 6d, and the weekly subscription 3d, provoked great differences of opinion, and it was finally decided the latter should be 2d…

This settled, the Warwickshire Labourers’ Union was born.

Support From Different Quarters

Support for the newly formed Warwickshire Labourers’ Union and the striking farm workers soon came in from different quarters. The Daily News on 25 March 1872 ironically relates below such support, the writer making it clear that they did not agree with the push for better wages:

Professors Fawcett (42, Bessboro’-gardens) and E.S. Beesly (London University), Mr. Auberon Herbert, M.P. (Old Brompton), and Mr. F. Wilson (3, Berners-street), will gladly receive subscriptions for the relief of the poor down-trodden men who have ‘struck’ because Sir Charles Mordaunt and his neighbours will not give them more than 12s a week.

Sir Charles Mordaunt was a prominent landowner in Wellesbourne, where the strike had begun, whilst Professor Fawcett was Henry Fawcett (husband of leading suffragist Millicent Fawcett), who became one of the most vocal supporters of the striking farm labourers. Fawcett on 2 April 1872 was quoted by the Sun & Central Press as saying ‘that the present movement in Warwickshire is probably one of the most important that has ever taken place among our labourers.’

Meanwhile, the same paper gives Irish-born parliamentarian Robert Richard Torrens’s opinion of the strike, which was based upon his experiences in Australia:

In Australia a good agricultural labourer earns throughout the year 30s per week. In England the same man gets, in money and perquisite, 12s a week, yet the cost of a given piece of work, such as trenching a rod of ground, is not materially less in England than in the colony. The explanation is simple. One man in Australia, cheerful and hopeful, well fed, and living in cleanliness and comfort, is found to perform as much work as two of the exhausted, depressed, and half starved labourers in England. English farmers would do well to make the experiment.

A few days later the Sleaford Gazette reported on the monthly meeting of the Farmers’ Club in London, where Mr. W. Clutton, of Penge, stated how ‘there was no reason why agricultural labourers should not strike as well as bricklayers and carpenters, who had always received a great deal more money, and therefore farmers should be prepared for what was coming.’ This was not a popular opinion amongst his peers at the Farmers’ Club.

Support came from another prominent personality in the shape of famed Baptist preacher Charles Spurgeon. In an address given at the Metropolitan Tabernacle’s Colporteurs’ Association, he was quoted by London’s Echo newspaper on 10 April 1872 as saying:

The condition of the agricultural labourers was most shameful, and he had not rejoiced in anything more than when he heard they had begun to stir and combine for their own interests. He wondered they had not gone out on strike long ago. No doubt if wages were raised farmers would complain they were pinched.

A ‘Great Calamity’

Such support was not widespread amongst the farmers. The Daily News on 25 March 1872 outlined how:

The farmers are determinedly opposed to the union, which they assert, by organizing a general strike at a critical season, might put them to great inconvenience, and subject them to very heavy loss. Some farmers have already discharged all the men in their employ, and other union men are under notice.

A key figure in this resistance to the strike and new trade union was landowner Sir Charles Mordaunt, who owned Walton Hall, near Wellesbourne. According to the Daily News, he set about evicting his tenants who belonged to the union from their homes in the villages of Wellesbourne and Walton.

Those farm labourers who joined the strike were faced with harsh repercussions. The Daily News described how Thomas Chambers, a waggoner from Ailstone, was fined £2 at the Warwick Quarter Sessions for ‘leaving work without notice,’ having joined the strike effort. Meanwhile, striking labourers were faced with a lack of income, the union not yet having a ‘savings-box to break open.’

As the strikers gathered together, so did the farmers. The Sheffield Independent on 5 April 1872 reported on a meeting of farmers in Birmingham. At this meeting, ‘it was agreed that the labourers had a grievance, but the union was regarded as a great calamity.’ It was, therefore, resolved that the group ‘should do everything in its power to improve the condition of the labourer’ in order to prevent further strike action.

At this time unions were associated with a kind of lawlessness, as they were seen to represent a dangerous rejection of the fabric that held society together. This attitude was not helped by such instances like the threatening letter sent to Mark Phillips, a farmer from Welcombe in Warwickshire. The Shields Daily Gazette on 9 April 1872 printed the anonymous missive:

‘I am a man with a family, and a union man, and expect nothing but starvation, as I expect the sack; and before my family shall starve under the laugh and scoff of a farmer I will murder the lot; and woe to the man that is the occasion of it.’

A ‘Great Triumph’

Aside from such instances, the union and the farm labourers’ strike gained traction, and importantly, results. The Daily News on 25 March 1872 reported how:

The farmers hate the union, of course; but seeing the rapid progress it is daily making, and seeing, too, the determination of such a large body of men, they are left little choice between union men and no men. Lord Leigh has, we believe, advanced his men’s wages to 15s. A few other employers near Leamington have done the same, or gone as far as 14s.

Indeed, the same article related how ‘half of those on strike have got employment at the advanced price’ of 16 shillings. As April progressed, the Sheffield Daily Telegraph on 10 April 1872 provided this update from Warwickshire:

The farmers are willing to pay their labourers 14s a week from Michaelmas to Lady-Day, and 16s from Lady-Day to Michaelmas, with the exception of the harvest season, or 15s all the year round. They propose that the payment during harvest season should be left to be agreed upon between the farmers and the labourers, and to be definitely arranged at least a month previous to the commencement of the harvest season.

The strike had brought this agreement to fruition and proved to be a success. Meanwhile, the impact of the strike and the unionisation of farm labourers was also being seen outside of Warwickshire, the Evesham Journal on 13 April 1872 reporting:

At a meeting of farmers at Great Withy (Worcestershire), it was decided to give an increase of 2s weekly to ordinary labourers, and 3s to waggoners, and that the men should be able to draw their wages entirely in money.

The Movement Spreads

The strike movement of the farm labourers was spreading. Warwickshire newspaper the Stratford-upon-Avon Herald on 5 April 1872 reported how ‘it is said already to have spread into eight counties.’

Warwickshire, however, remained the epicentre of the strike action. Moving into May of 1872, the Newcastle Journal reported on a meeting of the Warwickshire Labourers’ Union. During this meeting, a conference between members of the union and delegates from the Warwickshire Chamber of Commerce was agreed.

It was Leamington, within Warwickshire, that continued to be the centre of the movement. The same Newcastle Journal article reported on another meeting of ‘agricultural labourers and their friends’ in the town. During this ‘large meeting,’ the unionists were congratulated by speaker Mr. Jenkins on ‘their encouraging and wonderful success.’

Strikes amongst agricultural labourers continued. The Newcastle Journal on 10 June 1872 reported on another strike in Warwickshire, this time in the Cubbington district, where there was ‘an agricultural population of 2,000.’ Cubbington was home to ‘strong branch of the Labourers’ Union’ since the beginning of the union movement.

The Cubbington labourers had asked for ‘the Union terms -16s a week for nine and a half hours a day, and 4 1/2d per hour for overtime.’ Their request refused, between 300 and 400 farm labourers went on strike. The Newcastle Journal remarked:

This is the first collision that has occurred between the farmers and the Labourers’ Union, and the contest will probably be characterised by considerable determination on both sides. The labourers seem confident of victory, as the hay harvest will shortly commence, and the masters have no organisation in opposition to the union.

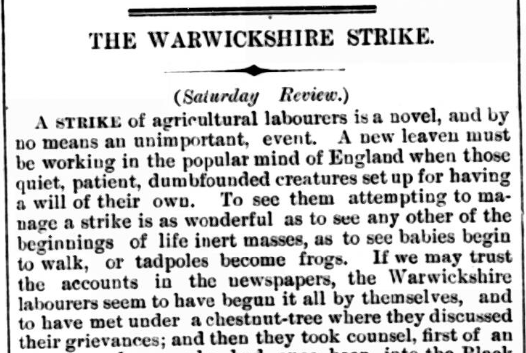

A ‘Novel’ Event

The impact of the farm labourers strike is an incredibly important one, in which the condition of the rural worker was put under a microscope in a way that had never been seen before. As the Shipping and Mercantile Gazette pondered on 30 March 1872, ‘the men at Wellesbourne, without so much as a week’s wages in hand, with a habit of endurance, with heavy families to feed, could have brought themselves up to strike, they must have been near ‘despair.”

Kolkata newspaper the Indian Statesman perhaps sums this up most effectively and eloquently in a piece published on 27 April 1872:

A strike of agricultural labourers is a novel, and by no means an unimportant event. A new leaven must be working in the popular mind of England when those quiet, patient, dumbfounded creatures set up for having a will of their own. To see them attempting to manage a strike is as wonderful as to see any other of the beginnings of life inert masses, as to see babies begin to walk, or tadpoles become frogs.

The article went on to laud the trailblazing nature of the strike:

Distress has in old days led to rick-burning, and brutal ignorance has led to the destruction of farm machinery; but those were only the outbreaks of hungry or panic-stricken barbarism. But a strike, as a strike is said to have been conducted in Warwickshire, is a totally different thing. It shows a power of union, a perception of the respect due to law, a confidence that success can be achieved without violation of the law.

The strike, and the union had achieved something. With an average wage of 12 shillings, farm labourers were now generally receiving 14 or 15 shillings. As the Indian Statesman observes:

The difference between twelve shillings a week and fifteen is practically enormous. It means the difference between having just enough to keep body and soul together, and having some of the rudiments of comfort and plenty.

The movement that began as the Warwickshire Labourers’ Union would grow into the National Agricultural Labourers’ Union, with Joseph Arch at the helm. As signified by the name, it grew into a national force, reaching its peak in 1874 with over 85,000 members. However, during the 1880s, thanks to poor harvests and anti-union farmers, numbers shrank, so that the National Agricultural Labourers’ Union now only had less than 10,000 members. Despite a fresh campaign led by Joseph Arch in the 1890s, which saw widespread support in Norfolk, the organisation was dissolved in 1896. However, it represents an important part in Britain’s labour history, and a landmark movement in Britain’s agricultural past.

Discover more about rural history, strikes, trade unions, and much more besides, in the pages of our Archive today.