This August at the British Newspaper Archive we are taking a look at the history of holidays, and in particular, the history of British holidaymakers travelling abroad. Nowadays, the holiday season is synonymous with trips to the airport, with holidays abroad bookable at just the click of a button.

Decades ago, however, travelling abroad was not that easy. With strict limitations on travel money, the difficulties of booking travel abroad, potential holidaymakers faced a range of challenges in getting away from the British Isles in order to enjoy a well-earned break. But from the 1920s onwards, more and more British people began to travel abroad for their holidays. And so, in this special blog, using newspapers taken from our Archive, we will take a look at the rise of the British holidaymaker travelling abroad.

Ease and Comfort

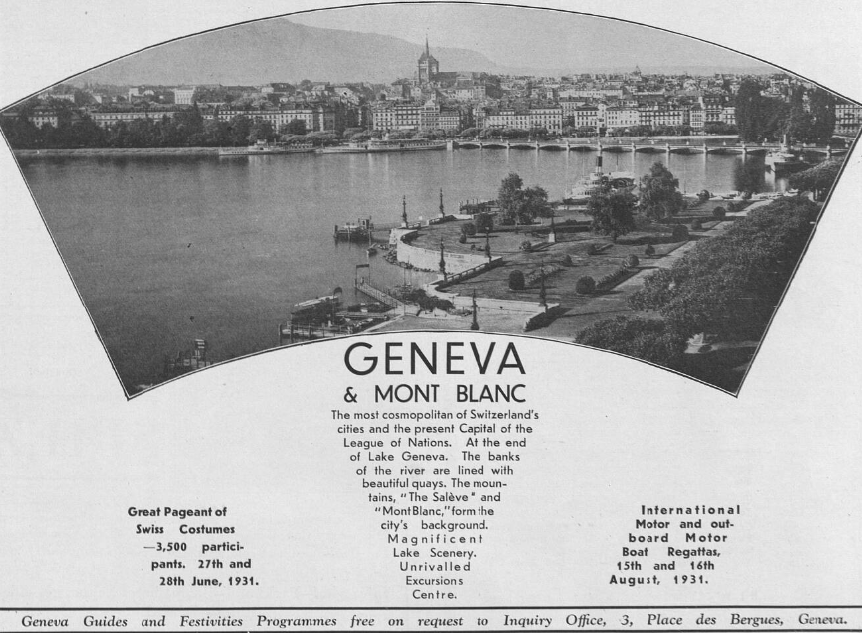

As Maxwell Fraser for the The Sphere in June 1931 observed, ‘travel has been made so easy and expeditious that even a holiday-maker with only two weeks at his disposal can reach any corner of Europe that attracts his fancy.’ Such advances in transport, such as cars, trains and even planes, had by the early 1930s opened up the option of holidaying abroad for the British population.

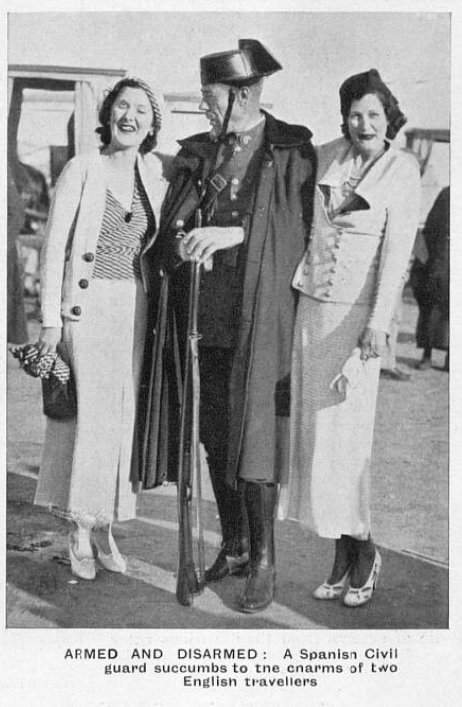

Meanwhile, in June 1939, just months before holidays abroad would be halted as the Second World War broke out, Bryan Broadstaffe extolled the virtues of ‘Summer Holidays Abroad‘ for The Tatler. Broadstaffe observed how:

It is not surprising that holidays abroad are very popular with people in this country, since the facilities offered by the various railways and air lines for crossing to the Continent in ease and comfort are so numerous and up to date, whilst the concessions offered by various Continental railways, combined with extremely moderate hotel prices, make the proposition an extremely attractive one from the point of view of one’s purse.

Travelling abroad was a popular pastime, an idea that Broadstaffe digs into a little further, as he explores the benefits of holidaying away from Britain:

There is, too, a great fascination in seeing foreign lands and in making their acquaintance with their peoples, and apart from the pleasure this gives, there is the knowledge one acquires of other view-points concerning the questions of the day, and, in a lighter vein, there is the joy of discovering new and delightful methods of cuisine and wines of rare vintage.

This passage is more than a little poignant with its nod to the ‘questions of the day,’ such questions that would soon engulf the world in another devastating conflict.

See Britain First?

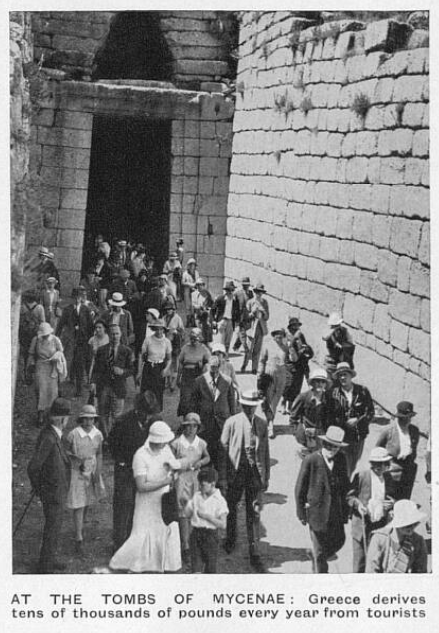

Meanwhile, J. Baker White, writing for The Sphere in October 1934, traced this recent phenomenon of holidaying abroad back to the ‘days of the Grand Tour,’ for since this time, ‘the British people have been great travellers for pleasure.’ Of course, the Grand Tour was an experience that was in the main reserved for the sons of the aristocracy, who could afford to spend a year or two taking in the sights of Europe.

Travelling abroad in the 1930s, and even in the decades following this time, as we shall see, was an option only really available to the comfortably well off, who in 1930, according to Baker White, ‘spent £32,000,000 abroad.’ Visitors to the UK, meanwhile, spent £21,600,000, creating a deficit ‘of nearly £10,600,000 in our balance of payments.’

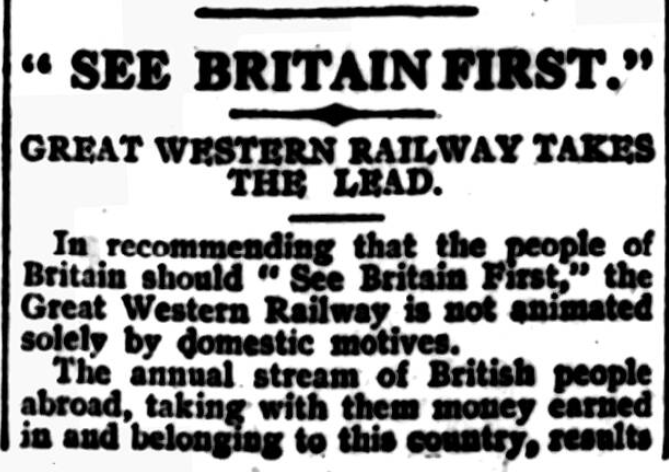

Such a disparity in spending led Sir Felix J.C. Pole, general manager of the Great Western Railway, to pen a nearly hysterical open letter in 1926, which recommended that ‘the people of Britain should ‘See Britain First.” The West Middlesex Gazette in March 1926 reprinted the letter, which made some bold assumptions about British people travelling abroad and its impact on the economy.

Pole believed that ‘the annual stream of British people abroad, taking with them money earned in and belonging to this country, results in an heavy financial lost for Britain.’ Indeed, he estimated that some £50,000,000 was ‘lost to Britain’ in this way, and so advocated the quasi-protectionist scheme of ‘seeing Britain first,’ designed to keep British money in Britain.

‘A Brighter and More Agreeable World’

Sir Felix Pole, some fifteen or so years later, would get his wish when the Second World War prevented all but necessary travel abroad. But as early as August 1947, ‘scenes at the terminals, letters home, meetings with friends either just back or just going, news in the Press – all tell that the big push of Continental travel is on.’

This was the observation of Ferdinand Tuohy for The Sphere, who penned how:

The eagerness of those seeking release abroad has assumed a feverish note, as if people see the chance of foreign travel slipping away from them again, almost before it had returned. Hints of further currency bans, together with an ‘anything may happen’ attitude to potential crises, stoppages and strikes, combine to produce this high-strung mood.

We can today relate this feverish eagerness of getting away to the relaxation of COVID-19 restrictions, with many keen to experience holidays abroad in case the opportunity might be snatched away again. However, for travellers in 1947, getting away was not in any way as easy as it is today. As Tuohy relates:

Travel is not much fun these days for most of those who embark on it. Save for the well-placed and the young and gay of heart, it is no easy matter, rather something of a contest requiring stamina, resilience, patience and self-control. But the prize is worth it – contact with a brighter and more agreeable, almost a gone world.

By July 1950 the Marylebone Mercury was reporting how the British people ‘are showing an increased tendency to travel overseas.’ The trend for travelling abroad was back on, with ‘a total of 521,807 new passports [being] issued last year, as compared with 424,544 in 1948.’

Adventures of Discovery

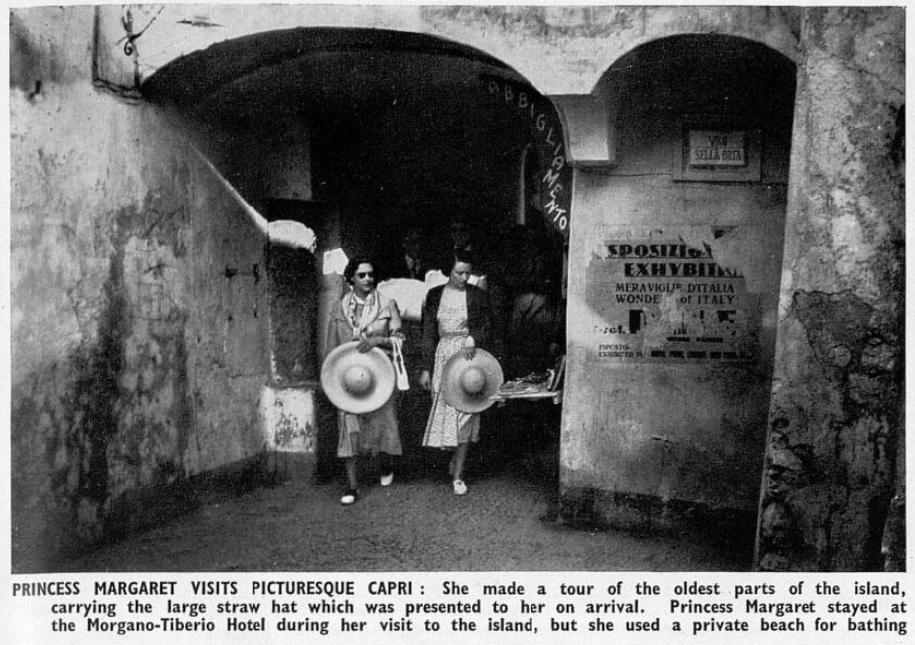

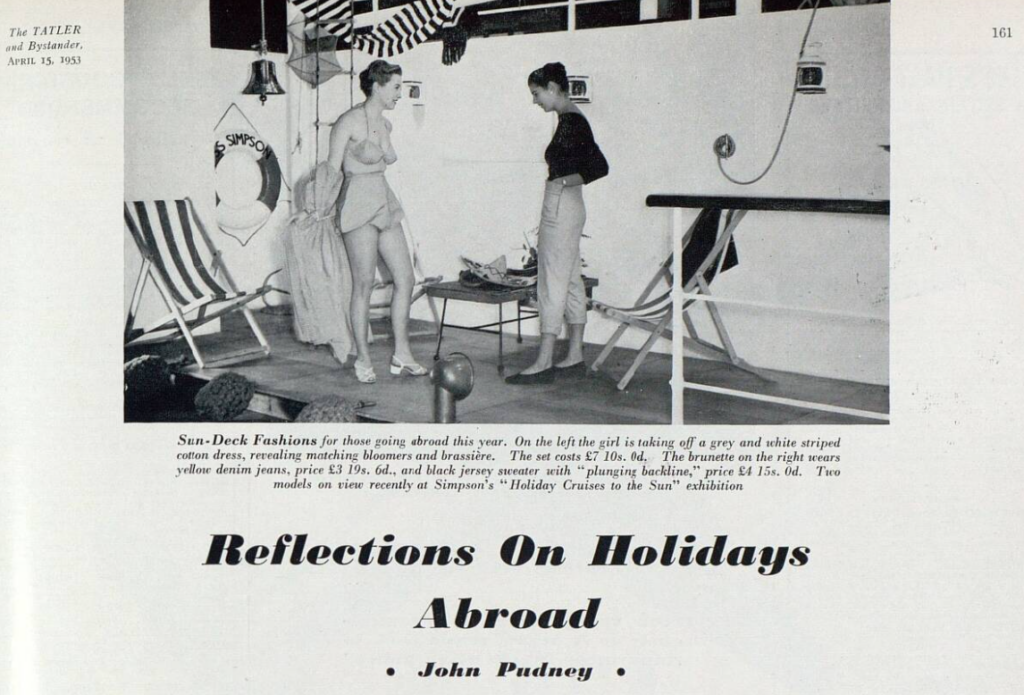

Thus began the 1950s, a pivotal decade in the trend for British people taking their holidays abroad. John Pudney, writing for The Tatler in April 1953, provided his ‘Reflections On Holidays Abroad.’ In this piece, he provides a riposte to the ‘people who say, ‘Isn’t England good enough for you?” – dismissing this as ‘muddled thinking, tinged with false patriotism, envy and insular timidity’ – and pontificating on the philosophy of travelling abroad, like Bryan Broadstaffe had done back in 1939.

Pudney observes:

Whatever the circumstances, there is a stimulus in seeing the difference of foreign parts…Holidays abroad are a part not only of present pleasure, but also of discovery and memory. Their stimulus does not pass. The adventure of discovery and rediscovery remains.

For Pudney, travelling abroad was all about curiosity, and it seems that he was not alone in such a desire to see the world beyond Britain. On 16 July 1953 the Sussex Daily News reported how ‘more people are going abroad,’ with ‘car traffic [being] particularly heavy.’ The piece also noted how ‘an increase by 30 per cent in special trains charted by travel agents to Austria and Switzerland is expected, and similar traffic to the South of France may well show an increase of 50 per cent over last year.’ Another popular destination was Yugoslavia, where a ‘number of parties’ had booked to visit.

Such trends continued into the following years, with the Bradford Observer on 20 July 1955 relating how ‘a record number of British people holidayed abroad last year.’ How were these people travelling? The paper relates that British holidaymakers travelled mostly ‘under agency direction,’ with the increase of the travel allowance to £100 and ‘air travel with is greater convenience’ fuelling such record numbers.

A Record Year for Foreign Travel

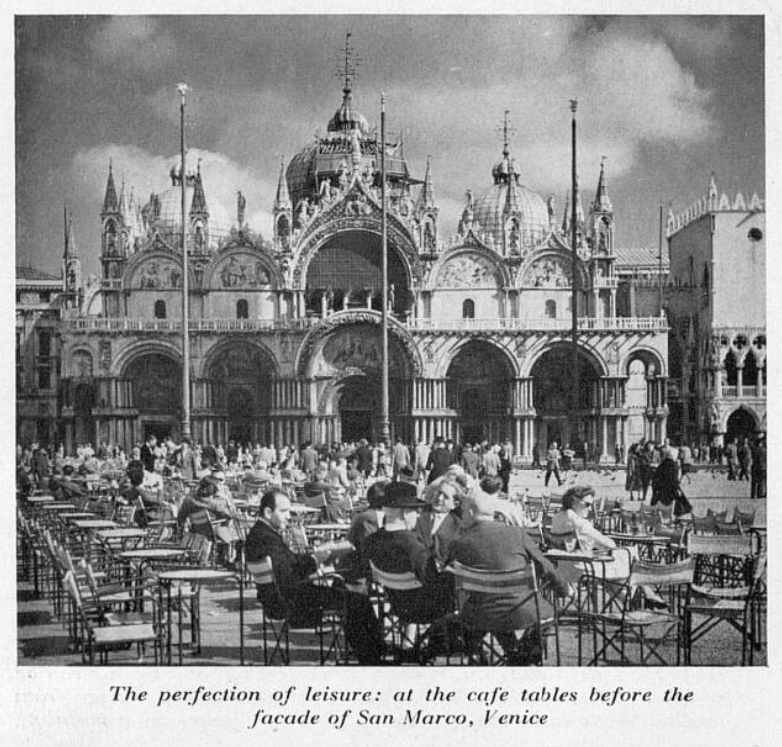

Again, the numbers continued to rise, the Kirriemuir Free Press and Angus Advertiser in September 1956 reporting how ‘more people went abroad for [their] holidays, with ‘eight per cent of those having a holiday in 1955’ going abroad. For these eight percent, the most popular destination was France, with Italy, Ireland and Switzerland being ‘the next favourites.’

However, despite these rising numbers, the Kirriemuir Free Press reported how ’77 per cent of the population have never been outside Britain.’ This statistic was compiled by the British Travel and Holidays Association, and points to that economic disparity, that the vast majority of Britons perhaps could not afford to travel abroad.

Meanwhile writers continued to reflect on the positives of holidaying abroad. Nigel Buxton writing for The Tatler in January 1958 observes how ‘it is not that all things in other countries are better; it is just that they are different, and in living differently one has the chance to escape for a while from one’s ordinary, too-familiar self.’ Indeed, he viewed travelling abroad as a form of enlightenment, such enlightenment may even leading to a time when it ‘is fashionable to renounce marmalade for breakfast in favour of strawberry of apricot jam.’

A few days later, Gordon Cooper provided the first of his guides to ‘Holidays in Europe‘ for The Sphere. In this piece, he tracked the trend of Brits travelling abroad, relating how ‘travel agents are already convinced that 1958 will be a record year for foreign travel,’ with two million people set to holiday abroad.

The Gentle Art of Travelling

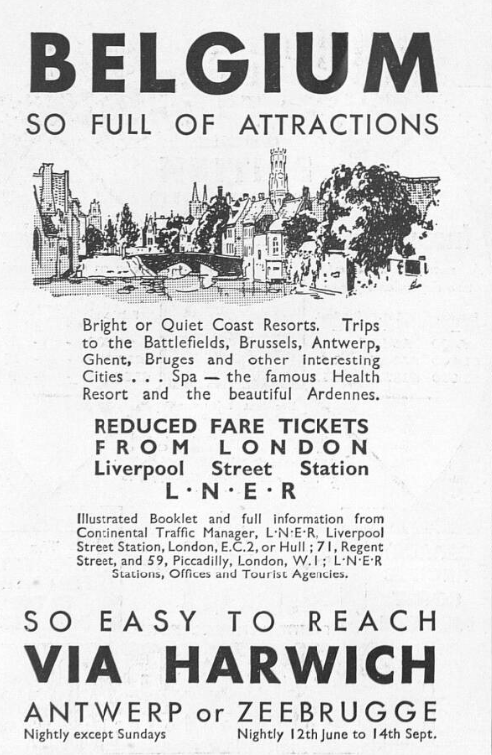

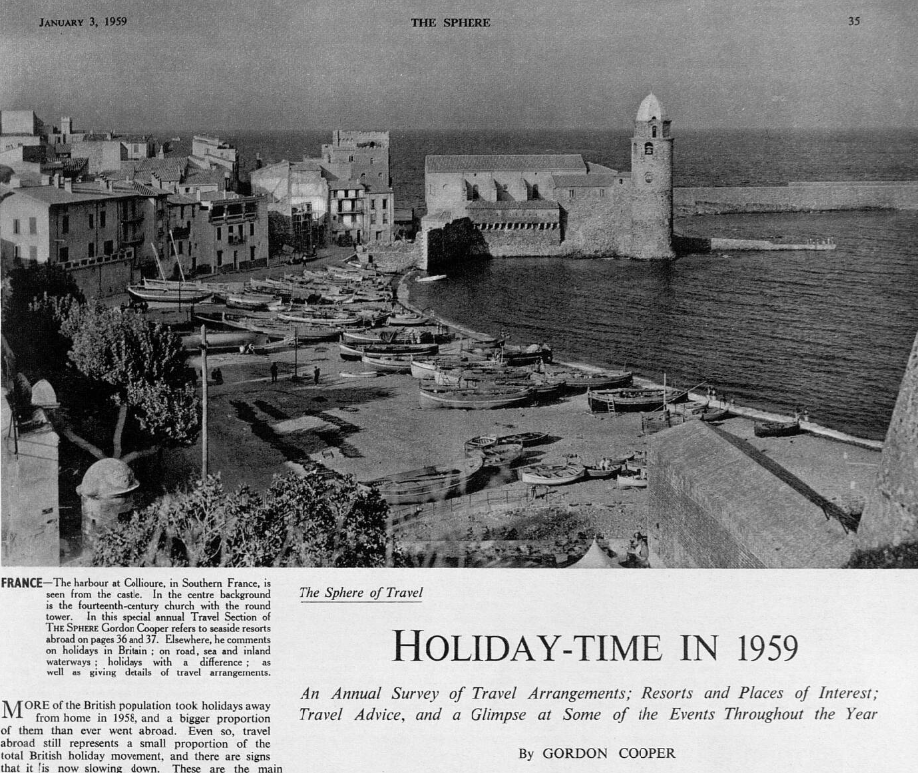

A year later, in January 1959, Gordon Cooper was back for The Sphere, reporting how the prediction for 1958 had come good. Some fourteen percent of ‘British holidaymakers went abroad,’ up seven percent from 1955. Cooper related how France, Germany, Switzerland, Belgium, Italy, Holland, Spain, Austria and Scandinavia were the most popular destinations for British tourists, with Belgium’s ‘relatively high position [being] undoubtedly due largely to its International Exhibition.’

Cooper went on to observe how ‘the recent boom in Spanish travel is tending to decrease, mainly due… to too fast development of resorts and hotels,’ a viewpoint that would not be borne out. However, he does make some useful comments on the infrastructure of travel, explaining how ‘in 1959 there will be in almost every direction better and cheaper transportation facilities.’ He points to the ‘fare reductions’ and ‘development of new routes’ by airline B.E.A., alongside cheap cross-Channel ‘vehicle ferry services’ and speedier continental train services.

Indeed, by January 1959, more ‘distant horizons [were] opening up.’ Cooper writes how ‘by air you can reach Athens, Beirut or Israel in less time than you would take to travel overland to the French Riviera.’

To him, however, this advancement in travel was not exactly welcome:

It is a melancholy paradox that the development of the means of locomotion has almost killed the gentle art of travelling. The word ‘travel’ in itself implies labour, and it would seem that the scientific elimination of toil from a traveller’s lot has deprived travel itself of its most exquisite essence and charm.

A Form of Snobbishness?

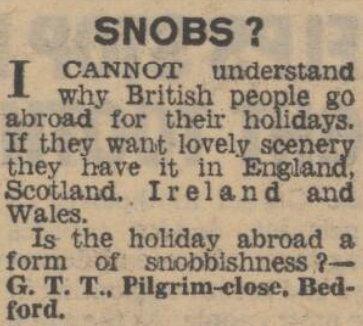

There were others by the 1960s that were not impressed by the trend for travelling abroad, albeit for different reasons than travel purist Gordon Cooper. One outraged letter writer of Pilgrim Close, Bedford, wrote to the Daily Mirror in September 1961, exclaiming how:

I cannot understand why British people go abroad for their holidays. If they want lovely scenery they have it in England, Scotland, Ireland and Wales. Is the holiday abroad a form of snobbishness?

By June 1963 the Inverness Courier reported how ‘although the numbers of British people taking holidays away from home in 1962 rose considerably over the previous year, the increase in overseas travel was small.’ Was the upwards trend in British people travelling abroad steadying? The paper recorded ‘how more than four million main holidays were taken by British people abroad in 1962 – with approximately half a million additional holidays,’ which was ‘roughly the same as 1961.’ But remember back in 1958 when two million was the record-breaking number?

And while, according to the Inverness Courier, in 1962 ’46 per cent of British people holidaying abroad travelled by air and 57 per cent by sea,’ with Spain, Italy and France being the preferred destinations, still ‘at least 29 per cent of British adults and children do not have a holiday.’ Or if they did, they elected to spend it at home, again suggestive of that economic disparity.

Fighting Back Against Foreign Holidays

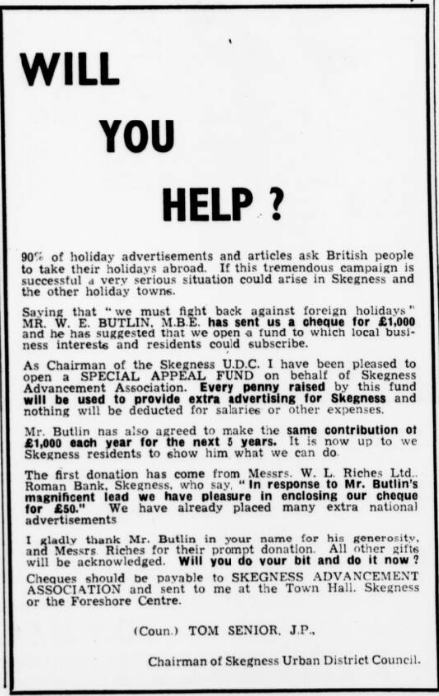

Meanwhile, Skegness and the might of holiday camp king Billy Butlin were ‘fighting back against foreign holidays.’ A letter penned by chairman of the Skegness Urban District Council, one Tom Senior, which was printed in the Skegness Standard in February 1964, outlined how ‘90% of holiday advertisements and articles ask British people to take their holidays abroad.’ If 90% of British people were then to take up these advertisements, Senior feared ‘a very serious situation could arise in Skegness and the other holiday towns.’

Tom Senior was ‘fighting back,’ however. Aided by a gift by Billy Butlin himself, of £1,000, Senior and the Skegness Advancement Association aimed to raise funds for ‘extra advertising for Skegness.’ It was now ‘up to we Skegness residents to show [Mr. Butlin] what we can do.’

Despite such efforts, the Kensington Post on 6 January 1967 reported how ‘more people than ever [are] going abroad.’ This also flew in the face of the government’s so-called ‘squeeze’ on holiday spending (a maximum of £43 per head being allowed for a fortnight’s spending on holidays overseas), which drove British holidaymakers to book their holidays ‘much earlier, and in much greater volume,’ in attempt to make their money go further.

The Trend Slows?

Into the 1970s, with the economic uncertainty of that decade, and the upwards trajectory of Brits travelling abroad seemed to have slowed.

Perhaps it was due in part to the misinformation and prejudice about foreign lands, which an article in the Newcastle Evening Chronicle in November 1972 described:

I once took part in a survey to find out why British people went abroad for their holidays and equally important why they did not. Although it was not at the top of the list for ‘staying at home’ one reason given by many folks for not venturing on to the Continent was that ‘it’s not as clean as here,’ or ‘everywhere is so untidy’ or ‘Mediterranean resorts can be really dirty can’t they?’ – and many more to that effect.

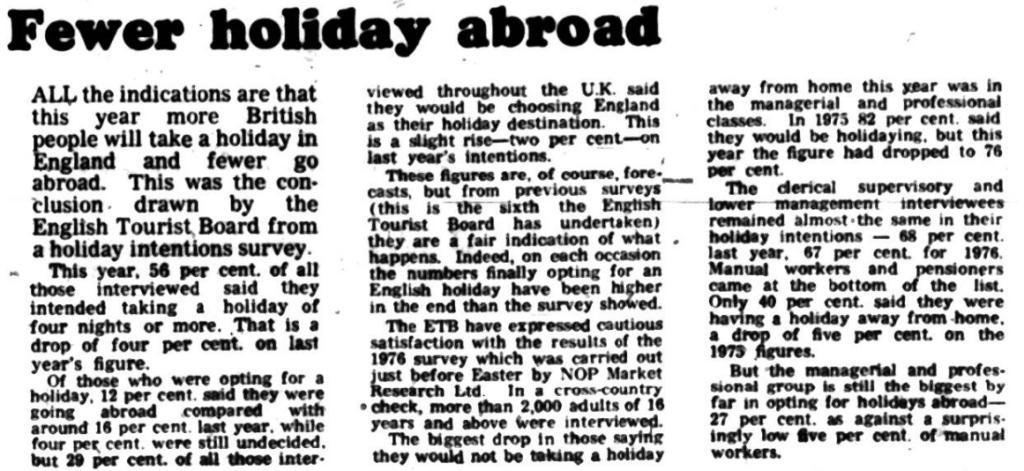

Luckily the writer drew attention to the UK’s own litter problem. By 1972 ‘twelve million trips were taken abroad,’ as reported the Suffolk and Essex Free Press, again up from that four million number of the decade before. However, in May 1976 the Newcastle Evening Chronicle reported how ‘all the indications are that this year more British people will take a holiday in England and fewer go abroad.’ According to a survey conducted by the English Tourist Board, only 12% of those who were planning to take a holiday were going to go abroad, ‘compared with 16 per cent last year.’

Moreover, this survey gave an important insight into the economic and class makeup of those choosing to holiday abroad:

But the managerial and professional group is still the biggest by far in opting for holidays abroad – 27 per cent as against a surprisingly low five per cent of manual workers.

The boom in Brits travelling abroad would finally come to its head when that class barrier was broken down, allowing more and more people to travel at increasingly lower rates, with cheap flights and affordable package holidays opening up destinations abroad in a way the travel writers of the mid 20th century could only imagine.

Find out more about the history of Brits travelling abroad, holidays, and much more besides, in the pages of our Archive today.