Just when did ‘Brits abroad’ get their bad reputation? And when did the phrase enter the vernacular? In this special blog, we explore the shocking history of the ‘Brits abroad’ stereotype, and learn how although this group of badly behaving tourists got their name in the 1980s, the British abroad have a long history of causing upset on their travels.

Last week, we looked at the rise of Brits travelling abroad using our newspapers, and this week, again using newspapers from The Archive, we uncover the ‘Brits abroad’ stereotype.

Register now and explore the Archive

‘The Loudest and Most Embarrassing’

The phenomenon of Brits abroad, as we know it today, was well established in May 2001 when John Innes penned an article for The Scotsman on the ‘Seven faces of Britons abroad.’ These seven profiles were based on research by travel firm JMC, but it was just one of these seven faces that Innes chose to focus on:

Dave and his mates have had a good night. They stagger from bar to bar, singing ‘Enger-lund, Enger-lund’- or possibly Flower of Scotland – while looking for a like-minded group of Tracys to chat up. These are the Brits abroad, the holiday-makers we want to avoid. Across the hot-spots of Europe, other tourists feign embarrassment at their outrageous behaviour, shrug and smirk, ‘Brits abroad, eh?’

Innes, in this description, neatly captures all our notions about Brits abroad. Indeed, out of the seven holiday profiles (which include ‘package pros’ like mid-twenties couple Mark and Lisa, and ‘mature hedonists’ like divorcees Roger and Beverley – find the full list here), the Brits abroad types are dubbed to be ‘the loudest and most embarrassing. They sing, drink and sleep around – and often spend holidays in Ayia Napa or similar places where they can be loud and proud.’

‘The New Barbarians’

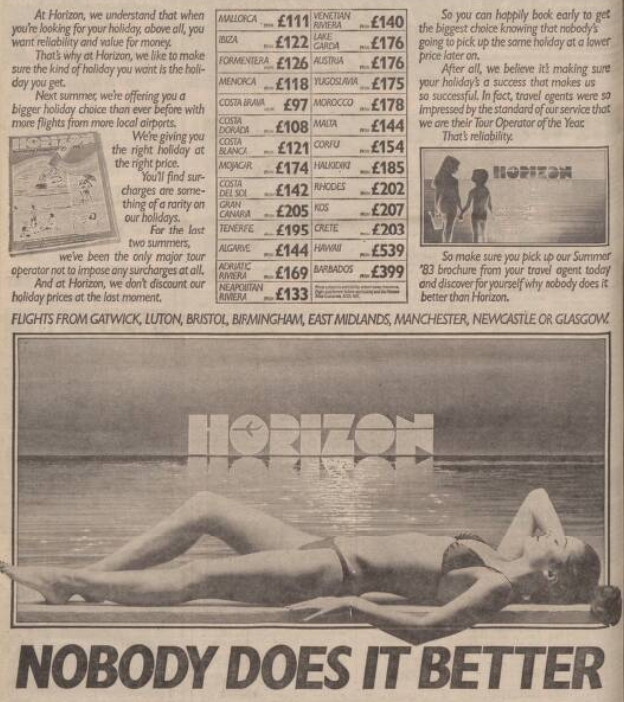

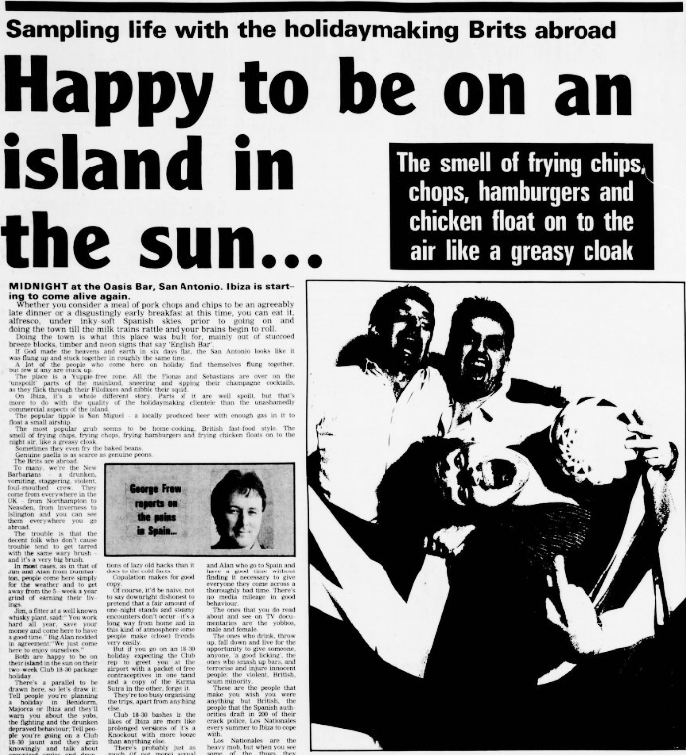

But how did we get here? Go back several decades to the 1980s and Northampton Chronicle and Echo journalist George Frew took himself off to Ibiza to learn more about Brits abroad. A tough gig, eh? By this time, cheap package holidays had opened up a range of destinations for Brits looking to escape the uncertainty of a British summer, and among these sunseekers Frew landed in the summer of 1987.

His piece began by juxtaposing the beauty of the Spanish island with the gaucheness of the British palate:

Midnight at the Oasis Bar, San Antonio. Ibiza is starting to come alive again. Whether you consider a meal of pork chops and chips to be an agreeably late dinner or a disgustingly early breakfast at this time, you can eat it, alfresco, under inky-soft Spanish skies, prior to going on and doing the town until the milk trains rattle and your brains begin to roll.

Frew then tackles the reputation of the Brits abroad themselves, writing how ‘to many, we’re the New Barbarians – a drunk, vomiting, staggering, violent, foul-mouthed crew.’ But was this generalisation fair?

Frew didn’t seem to think so:

The trouble is that the decent folk who don’t cause trouble tend to get tarred with the same wary brush – and it’s a very big brush. In most cases, as in that of Jim and Alan from Dumbarton, people come here simply for the weather and to get away from the 5-week a year grind of earning their living.

Jim and Alan were on a ‘two-week Club 18-30 jaunt,’ and were simply ‘happy to be on their island in the sun.’

A Few Bad Apples?

However, it was precisely such holidaymakers like Jim and Alan, the Brits abroad on their Club 18 to 30 trips, that leant such places as Benidorm, Majorca and Ibiza their reputation for ‘the yobs, the fighting and the drunken depraved behaviour.’

George Frew ended his Ibiza exposé for the Northampton Chronicle and Echo on September 1987 by highlighting the bad behaviour of a few bad apples, which had given Brits abroad generally such a bad reputation:

In San Antonio, the…minority of Brits lose their senses, their self-respect, their dignity, their liberty and sometimes even their own lives. Perhaps it’s no coincidence that St Anthony is the recognised patron saint of lost things.

But according to the Aberdeen Press and Journal just a year later, in August 1988, crimes committed by British holidaymakers were on the up:

A crimewave among British tourists in Greece has led to a sharp increase in arrests, Foreign Office Minister Mr Tim Eggar said yesterday. Mr Eggar said most of the arrests could be put down to burglary and petty theft when tourists ran out of money.

The Aberdeen Press and Journal also reported how the 8 million Brits holidaying in Spain had ‘seen an increase in arrests,’ again mainly for ‘the same trend of burglary and petty theft.’

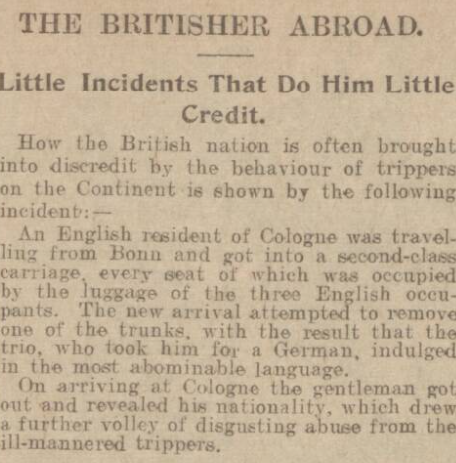

‘Little Incidents That Do Him Little Credit’

Delving into our Archive we found that British tourists abroad have a long history of behaving badly. These holidaymakers may not have been known as ‘Brits abroad’ (a phrase that broadly came into use in the 1980s), but our newspapers do reveal troubling stories of ‘The Britisher Abroad.’

Take, for example, a small article that was published in the Dundee Evening Post on 16 September 1903 with the heading ‘The Britisher Abroad – Little Incidents That Do Him Little Credit.’ The piece explained how ‘the British nation is often brought into discredit by the behaviour of trippers on the Continent,’ providing this example to back up the claim:

An English resident of Cologne was travelling from Bonn and got into a second-class carriage, every seat of which was occupied by the luggage of the three English occupants. The new arrival attempted to remove one of the trunks, with the result that the trio, who took him for a German, indulged in the most abominable language.

The Cologne resident had the last laugh however, for when the train pulled into its destination, ‘the gentleman got out and revealed his nationality, which drew a further volley of disgusting abuse from the ill-mannered trippers.’

The Rising Bitterness

This was the early 20th century, and we tip back into the late 19th century to find more examples of badly behaving Brits abroad. Likewise published under the headline ‘The Britisher Abroad,’ but this time in national title the Globe on 13 March 1899, it was reported how one British consul, who had served in a Mediterranean port, ‘gave vent to the bitterness, which, during years of service, had accumulated in his mind against his travelling fellow-countrymen.’

The consul had ‘more that twenty counts in his indictment’ against his fellow Britons, but the Globe was able to collate the highlights for its readers:

…what he [the consul] most complained of was that the Englishman abroad expects his Consul to correct all the vagaries of foreign railway companies, to find lost luggage, cash cheques, provide funds to ‘send people home,’ advance money on notes of hand, to introduce the traveller to the best clubs in the place, to meet him at the station if asked, and to take him round to ‘see things.’

This is a different type of Brit abroad. This is an entitled tourist, who expects things to be the same as they are back home, born, no doubt, of centuries of colonialisation as well shall see.

‘The Snobbishness and Caddish Insularity’

On 22 June 1893 the Shields Daily Gazette reported on ‘the snobbishness and caddish insularity which our critics hold to be characteristic of the travelling Englishman.’ Now, the piece described how it was the French who took the most exception to the behaviour of Brits abroad, but it was actually detailing an attack on the behaviour of British travellers published across the pond by the New York Tribune.

This piece, in addressing ‘The Britisher Abroad,’ did not hold back:

In no other country of the world…have I found such an undisguised contempt for the foreigner as amongst the English. They are firmly convinced everything alien is necessarily bad; that foreign opinion is not worth considering; and that when dealing with foreigners they are under no obligation to observe the conventional rules of life which govern their intercourse with their fellow countrymen. The result of all this is that no people are more justly abhorred abroad than the ordinary Briton on his travels.

Here we see the theme of superiority emerging; in that British travellers regarded both themselves and their country as better, born no doubt after years of invading and colonialising other countries.

‘Figures of Fun’

The long piece, as reprinted by the Shields Daily Gazette, went on to attack the clothing of British people travelling abroad:

Englishmen, and I may add Englishwomen, do not seem to have the slightest consideration for their surroundings when abroad in the matter of dress; their one delight would appear to be to endeavour to offend the susceptibilities of the foreigners with whom they are brought into contact, either by the inadequacy or else by the exaggerated and equally inappropriate magnificence of their attire.

Indeed, the clothing of Brits abroad was a subject revisited by Manchester Evening News Fashion Editor Dianne Robinson in July 1992, when she described how:

Brits abroad used to be figures of fun. We had a dreadful beachside image of pallid little faces and either limp anaemic shorts or the kiss-me-quick vulgarity of obscene sloganed T-shirts.

Robinson was confident that times had changed, whilst she was on hand to assist with ‘some strong looks and colours that are perfect for the summer.’ But the New York Tribune attack on clothing was a more profound attack on not simply an aesthetic, but a insidious behaviour of demeaning other cultures, by either dressing too casually, or too extravagantly.

And whilst the Britisher abroad caused offence through his manner of dress, the New York Tribune detailed how offence was caused deliberately and openly:

He [the Britisher abroad] ridicules the language…he ridicules the accent, the appearance, the manners and the dress of all those whom he encounters abroad – not quietly and unobtrusively, but in the most offensive and public way, without the slightest idea of concealment.

‘We Bring All Our Troubles on Ourselves’

Thirty years before this piece was published, the Exeter Flying Post on 25 November 1863 published a letter that had originally been featured in The Times, under the heading ‘The British Abroad.’ This is one of the earliest examples we found of British people behaving badly abroad (aside from of course war and conquest). The letter had been written by a person with ‘experience extending over fifteen years in various parts of the world,’ who was of the firm belief that:

I believe we bring all our troubles upon ourselves, and most richly deserve them; for wherever an Englishman goes he carries with them the belief that his country is so rich and powerful, and that he himself is such an august animal, that he can trample the manners and cherished customs of other nations under his feet with impunity.

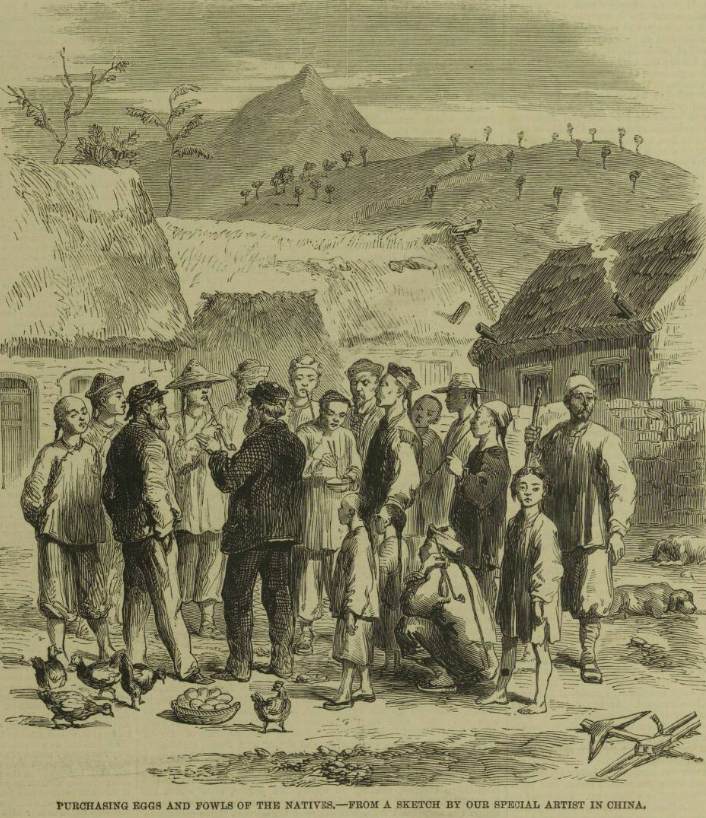

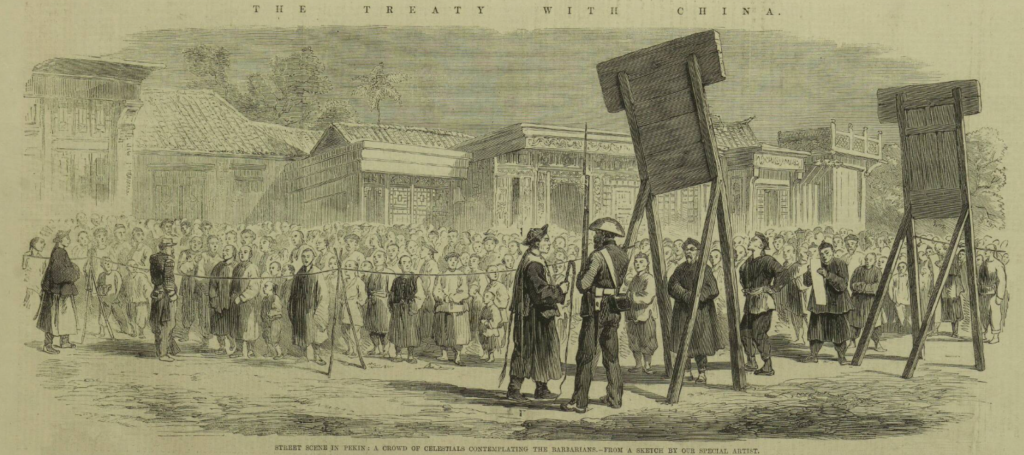

Again we meet with the same superiority theme. Now, the writer was keen to provide an example ‘of the things done abroad by Englishmen which, if done by any foreigner in this country, would bring upon him instant punishment at the hands of the people.’ Interestingly he chooses an anecdote which took place ‘two or three days after we took possession of Pekin [Beijing],’ tying bad behaviour of the British abroad with their unceasing colonialisation. The perpetrator of this particular incident is described as Irish too, but he would have been seen as British at the time, again because of same issue of colonialisation:

We were on a narrow footpath, on either side of which was a ditch of filth about twelve or fourteen feet wide. Now, it is the custom in China that when two people meet neither gives way for the other to pass, but both give way in a sidelong fashion. We met several people who stood still and sidled in this manner, but my companion was not satisfied with this; he said ‘the people he met should make way for him, and that the next who did not do it should go into the ditch.’

What happens next was awful, as you might expect:

Almost immediately a young Chinese dandy, dressed in his silks, his pet bird perched on the stick in his hand, and his face covered with smirks and smiles, came up to us, and stopped as usual. My companion, who was a young Hercules, took him up by the middle and flung him bodily into the ditch, from which he scrambled to the other side, half stifled and blinded with the filth which covered him.

Although this incident was witnessed by ‘some hundreds of people,’ it did not result in any repercussions for the writer’s companion. Instead, the crowd uttered a ‘roar of laughter,’ and the pair ‘walked on unmolested.’

As we can see, the notoriety of Brits abroad stretches back a long way, and has ties to Britain’s long history of conquest and colonialisation. Whilst Brits abroad in the modern era may stick to booze and antisocial behaviour, the legacy of disregard and disrespect for their hosts in other countries stems from an endemic sense of superiority, linked to notions of empire and control.

Find out more about Brits abroad, the history of holidays, and much more besides, in the British Newspaper Archive today.