This October we’re exploring the historical superstitions and traditions from across the British Isles and Ireland. Here, we’ve compiled 30 of the most intriguing historical superstitions, sourced from our newspaper collection.

From the more well-known superstitions, for example, not passing underneath a ladder, or throwing spilled salt over your shoulder, to those you may not have heard of, like giving a knife along with a penny, anyone?), without any further ado, here are 30 fascinating superstitions from history for you to peruse. How many have you heard of?

Register now and explore the Archive

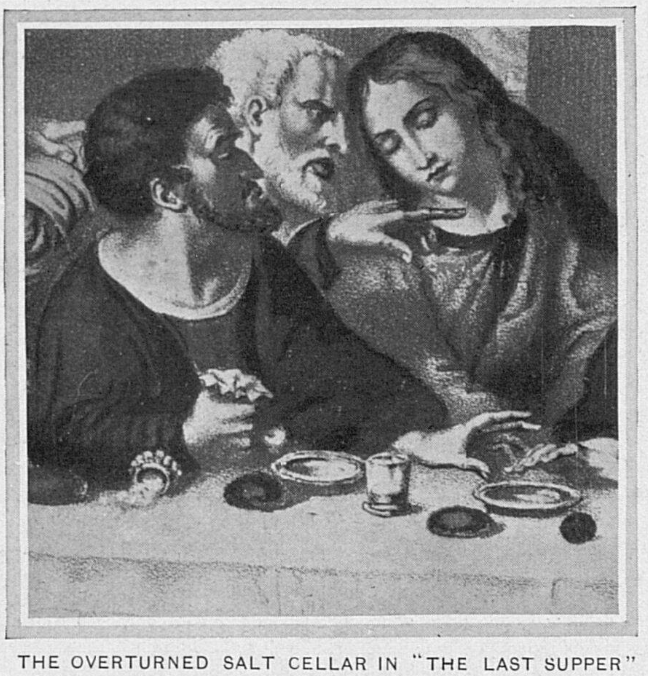

1. Spill salt to incur divine displeasure

We probably all know someone who is likely to throw spilled salt over their left shoulder. But why do they do this? This is perhaps one of the more ancient superstitions from our list, with the superstition dating back to Roman times. On 27 May 1926 the Gloucestershire Echo told its readers:

The superstition concerning the spilling of salt is derived from the ancient Romans, who used salt in their sacrifices and regarded it as sacred to Penates. Hence to spill it carelessly was to incur the displeasure of these household divinities.

But how was throwing salt over the left shoulder meant to rectify this divine displeasure? The Gloucestershire Echo explains:

After accidentally spilling the salt, the ancient Roman was wont to throw some over his left shoulder – the shoulder of ill omen – thereby hoping to call away from his neighbour the wrath of the deity, and turn it upon himself.

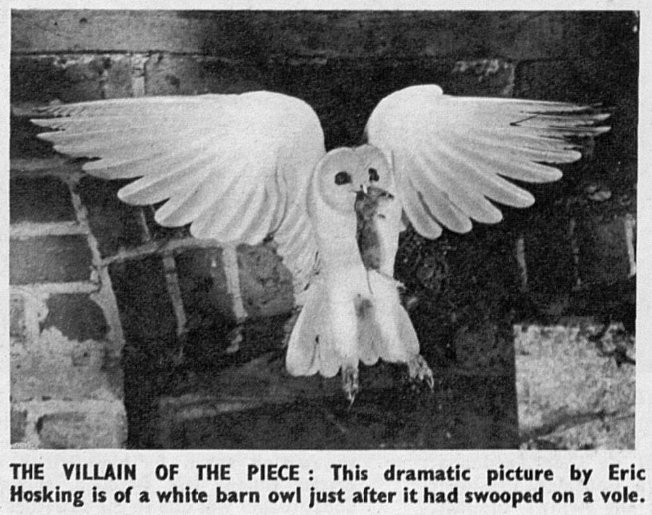

2. Owls as omens

Many superstitions are tied to fears of bringing on bad luck, and this is true of the superstition attached to the call of the owl. On 20 November 1954 The Sphere published an article by Brian Vesey-Fitzgerald about his visit to a group of Romany Gypsies, during which the hoot of a tawny owl was heard. According to Vesey-Fitzgerald, the oldest woman of the group muttered ‘Veshengo mulo’ a few times, the phrase meaning ‘the ghost or spirit of the wood.’

For the group of Romany Gypsies, the ‘owl’s call was a warning,’ a call of foreboding. Vesey-Fitzgerald explains how ‘superstitions about the owl’ are widespread: from the Bible to Virgil and through to Shakespeare, cultures around the world have long regarded owls with superstition. Find out more here.

3. Hair of the dog

Now this superstition features a phrase you may well be familiar with – hair of the dog – but not in the context you may expect. Indeed, the full phrase we are looking at here is ‘the hair of the dog that bit you.’

Readers of the West Sussex County Times on 8 September 1888 were acquainted with this old tradition, when it reported on ‘the trial of an action for damage alleged to have been caused by the bite of dog.’ A child had been bitten by a dog, and their grandmother, an Irish woman, demanded access to the dog in question, so that she could ‘obtain some of the dog’s hair to apply to the wound caused by its teeth.’

The West Sussex County Times notes how ‘the physicians would probably say that a bunch of fibres applied to a bleeding wound will act as a styptic,’ thus perhaps accounting for the belief that application of the hair of the dog that bit you to the wound would cause the wound to heal. However, the newspaper questioned ‘why, in the belief of these people, the efficacy of the hair should be limited to the particular dog that inflicted the injury is yet to be explained.’

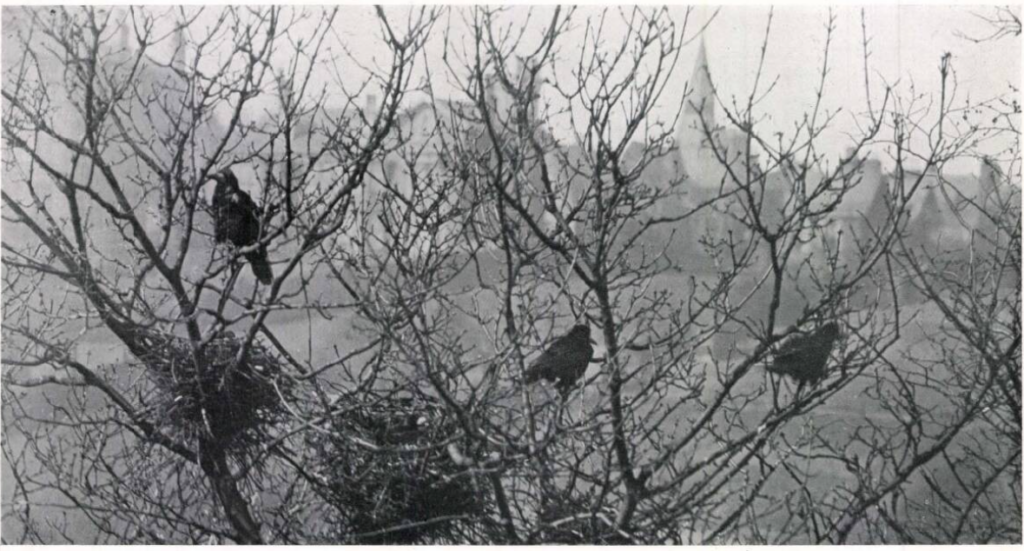

4. Leave the rookery alone

We staying in the animal kingdom now for the next of our historical superstitions. On 21 June 1937 the Bradford Observer reported on ‘Four Road Deaths‘ in the West Riding of Yorkshire. One of those tragically killed was 21-year-old Barbara Firth, who was a passenger in a car that skidded and collided with a bus.

However, despite the ‘greasy’ road conditions, locals in the area were quick to ‘connect Miss Firth’s death with an old superstition.’ Some fifteen months before, her father, Willie Firth, had cut down the trees in a rookery near the Firths’ home. Local superstition held to an ‘old belief…that it is unlucky to destroy a rookery.’

Barbara’s sad death wasn’t the only tragedy in the Firth family. According to the Bradford Observer, even before the ‘woodcutters had finished their work Mr. Firth died suddenly at the age of 43.’ And then, ‘nine months later, his only son, Rowland, aged 24, was concerned in a fatal motor accident at Yeadon.’

5. An usual use for a dead mouse

Our next two old superstitions are cut from a similar cloth, and have to do with healing a common childhood disease, whooping cough. According to one Dr. Felton, who was speaking at Grimsby in 1924, there were ‘plenty of people who still believe you can cure whooping cough by tying a bag containing a dead mouse round a child’s neck,’ as reported by the Lancashire Evening Post.

6. Once round a donkey’s belly

Another superstition around curing whooping cough was reported by the Greenock Telegraph and Clyde Shipping Gazette on 26 August 1882. This superstition came out of Lochee, where whooping cough was ‘rather prevalent.’ This cure involved ‘passing a child beneath the belly of a donkey.’

The paper went on to describe how a hawker with a donkey was stopped in Camperdown Street by two mothers, both of whom had children ‘infected with the malady.’ The mothers, ‘stationed at either side of the donkey, passed and repassed the little creatures under the animal’s belly.’ They then paused to feed some bread to the donkey, catching the crumbs from the donkey’s meal in their aprons, which they in turn gave to their poorly children, all in the hope of curing them.

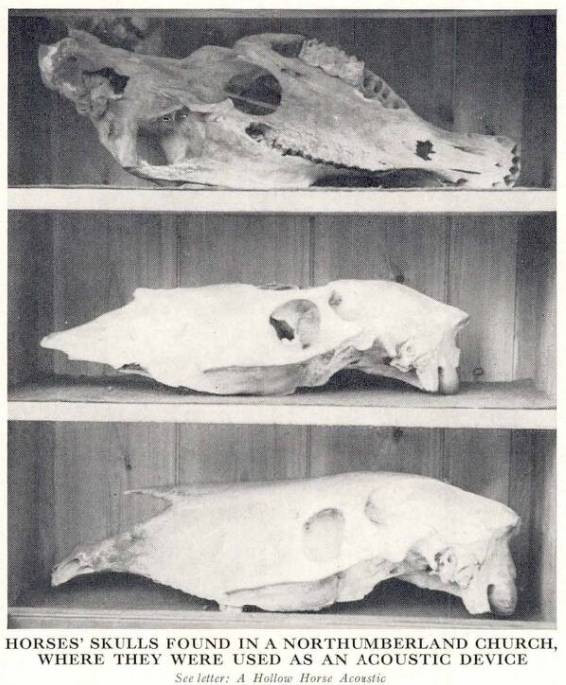

7. Horses’ skulls for skilled music

We’re continuing with our animal theme now with this slightly macabre superstition. Dubbed an ‘old Lakeland superstition’ by the Liverpool Echo in 1928, this tradition had it that ‘horses’ skulls improved the acoustics of music-rooms.’

The old superstition had been brought into the light thanks to renovations at Thrimby Hall, which lies to the south of Penrith. These renovations had ‘revealed…between thirty and forty horses’ skulls beneath the floorboards.’ The family at Thrimby Hall were ‘noted musicians,’ and it was thought the skulls leant something to their skill.

Incidentally the Liverpool Echo noted how the many skulls were ‘souvenirs from the nearby battlefield, where the encounter took place between the Young Pretender’s and the Duke of Cumberland’s forces in the Rebellion of 1745.’

8. The cuckoo before the nightingale

Back to our superstitions around ill omens, and on old superstition that was described by the Halifax Evening Courier in March 1925. At this time in the Halifax area, there was a rumour going around how the call of the cuckoo had already been heard. Meanwhile, in the countryside, there was a common superstition ‘that to hear the cuckoo before the nightingale is an extremely unlucky thing and an omen of dark forebodings to the unfortunate hearer.’

Indeed, the paper dated this superstition back to the days of Chaucer:

It was a common tale

That it were gode to here the nightingale

Mocke rathir than the lewde cuckowe singe.

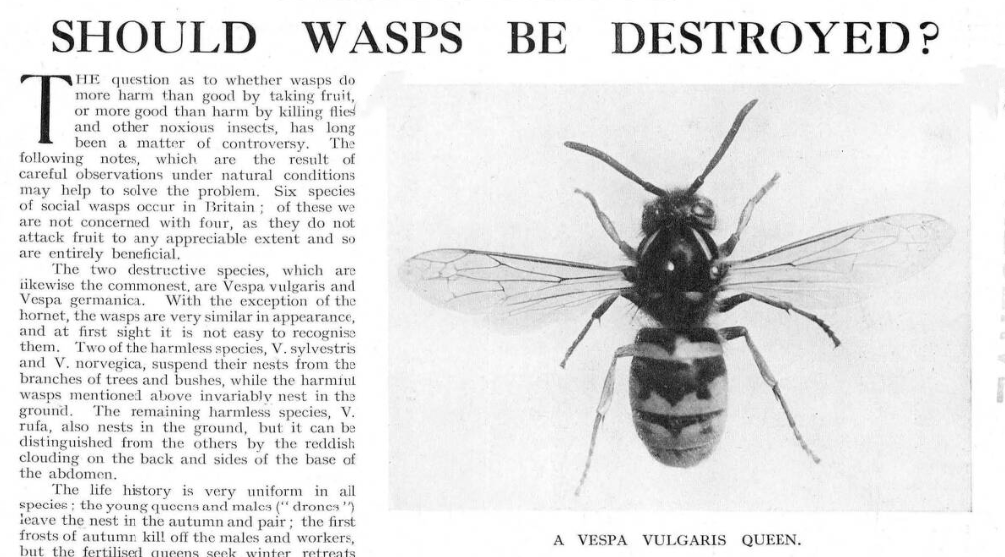

9. The doomed first wasp of the season

Another seasonal superstition surrounding wildlife was featured by the Aberdeen Press and Journal on 17 August 1911. The paper reported how ‘there is an old superstition, still prevalent in the Midland Counties, that the first wasp seen in the season should always be killed.’ But to what end?

Allegedly, the killing of the first wasp of the season would result in ‘good luck and freedom from enemies…throughout the year.’

10. A fishy curse

On 13 July 1920 the Globe newspaper reported on the plentiful catch of fish in the North of England, which had led to ‘all the fishermen on the coast near Berwick’ being at loose end. Of course, there was a market for fish ‘other than food,’ namely, for use as manure.

However, the Globe described a ‘superstition among the fishers of the North against selling entire catches of fish for any other purpose’ than for food. This stemmed from a curse laid ‘on the other side of Scotland’ by a woman, who was so angered by fish being used as manure in her area, that she placed a ‘curse upon the parties to the deal, and swore that nevermore, from the Gairloch to the Banks of Ballantrae, should fish be plentiful, or fisherman prosperous.’

According to the article, ‘old fisherman will shake their heads and tell you the curse still holds good – and superstitions travel far among fisher folk.’

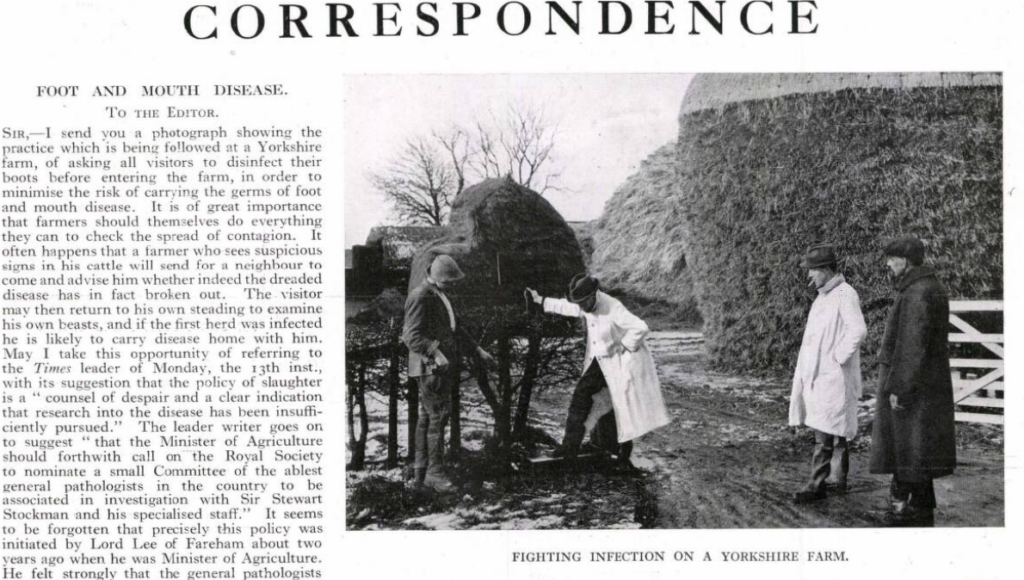

11. The year beginning on Sunday

We’re on to superstitions now that deal with dates and days of the week. The first of these is sourced again from the Halifax Evening Courier, this time from February 1922. This old superstition was recalled after ‘the widespread devastation of the foot-and-mouth disease, especially in the North of England’ caused ‘country people’ to speculate how ‘the outbreak might have been expected because 1922 began on Sunday.’

According to this ‘old tradition,’ that ‘whenever the first day of the year falls upon a Sunday there are sure to be many deaths of cattle and also of young men.’ If that wasn’t bad enough, the superstition also points to a ‘great increase in the number of robberies, indifferent harvests and possibly wars’ with the new year beginning on a Sunday.

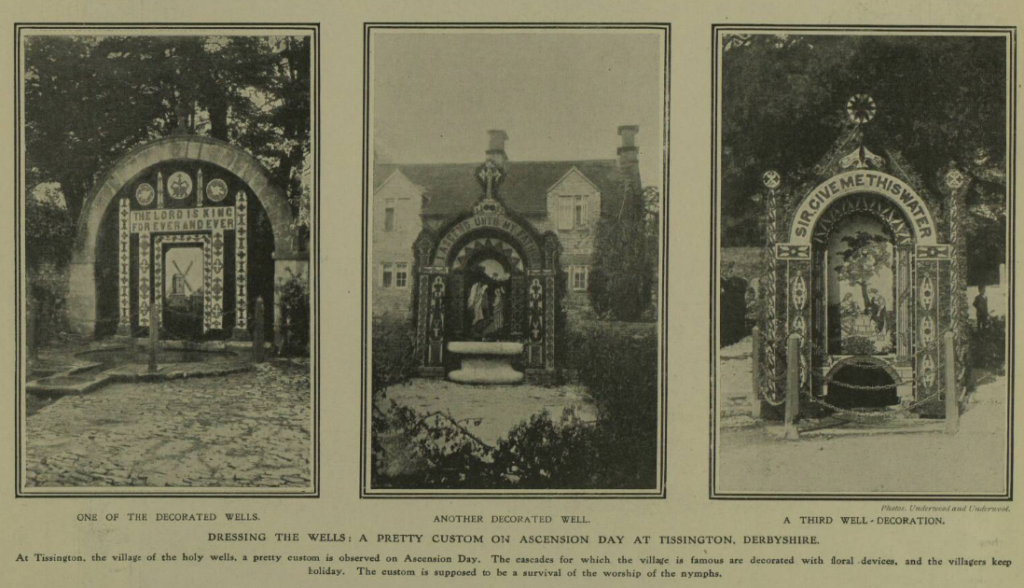

12. Ascension Day fatalities

Much in the same vein, the Lancaster Evening Post on 23 May 1925 reported on a old superstition that it was ‘fatal’ to work on Ascension Day. Indeed, the paper detailed how ‘workmen at Llangollen Quarries will have a free day in August as compensation for working on Ascension Day in disregard of an old superstition that it is fatal to work on that day.’

We’re not sure that superstitions can be deferred like this, but at least the workers got a day off.

13. The consequences of cutting your nails on a Sunday

We’re seeing a bit of a theme around historical superstitions and Sundays, and this superstition, from a rhyme published in the Berwickshire News and General Advertiser on 16 November 1954, perpetuates this link:

Cut your nails on a Monday, cut them for news;

Cut them on Tuesday, a pair of new shoes;

Cut them on Wednesday, cut them for health;

Cut them on Thursday, cut them for wealth;

Cut them on Friday, cut them for woe;

Cut them on Saturday, a journey you’ll go;

Cut them on Sunday, you’ll cut them for evil,

For all the next week, you’ll be ruled by the devil.

Something to bear in mind when you’re booking your next manicure!

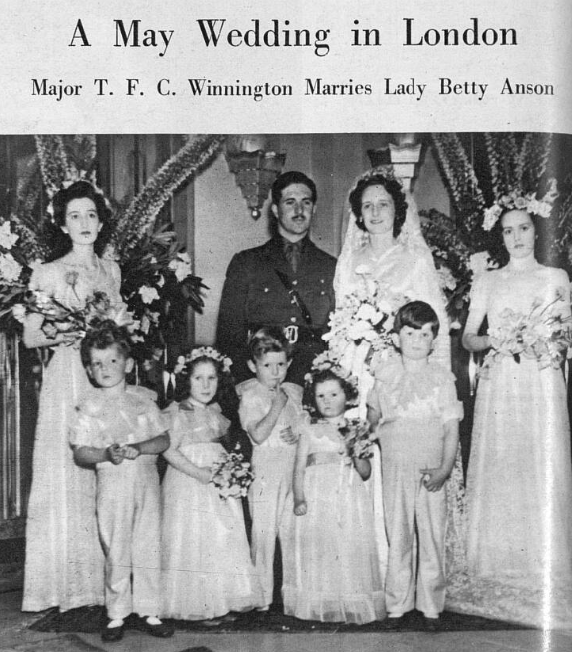

14. Wed in May…

There are a huge amount of superstitions surrounding weddings, probably enough to fill another blog. Perhaps one of the most well known superstitions is tied to the rhyme ‘Marry in May and you’ll rue the day,’ or ‘Marry in May is to rue it for aye,’ as described by a letter writer to the Aberdeen People’s Journal in May 1892.

Almost a decade before in June 1883 the Glasgow Evening Post addressed ‘an old superstition,’ most prevalent in Scotland but also held in the rest of Britain, that ‘May is an ill-omened month for wedlock.’ Indeed, this was backed by figures from the Registrar General, who reported how ‘the number of marriages in that month fall much below the average throughout the year.’

But why was this? The Glasgow Evening Post related how ‘in ancient Rome it was deemed unlucky to wed in May because the Lemuria, or festival of departed souls, was held in that month.’ For the Scottish, however, the fear of marrying in May can possibly be traced to something a little closer to home. It was during that month that Mary Queen of Scots made her ‘ill-omened’ vows to the Earl of Bothwell. After that particular match was made, the Ovid line ‘mense malas maio nubere vulgus ait’ was scrawled on the walls of Holyrood Palace, the Latin phrase translating to ‘bad marriages are made in the month of May.’

15. No green on the big day

Another wedding superstition revolves around the colour green. In July 1904 glossy magazine The Sphere described how the aristocratic Lady Evelyn Innes Wilson had broken ‘away from an old superstition in choosing pale green taffeta dresses for her bridesmaids.’ Indeed, it was thought that the colour green was ‘supposed to be very unlucky.’

This old superstition was again raised by the Leeds Mercury over 30 years later on 9 January 1935. The paper reported on the nuptials of Eleanor Tetley and John Goldney Kemm. Reportedly, the bride chose to wear a travelling costume of ‘deep dark green’ whilst the mother of the bride selected a ‘deep green’ shade for her dress, which was ‘made in the Medici style and worn with a picture hat of velvet trimmed with coq feathers.’ This colour choice caused the Leeds Mercury to observe:

Evidently neither the bride nor her mother has any regard for the superstition which clings to green – a dying superstition it seems to be nowadays.

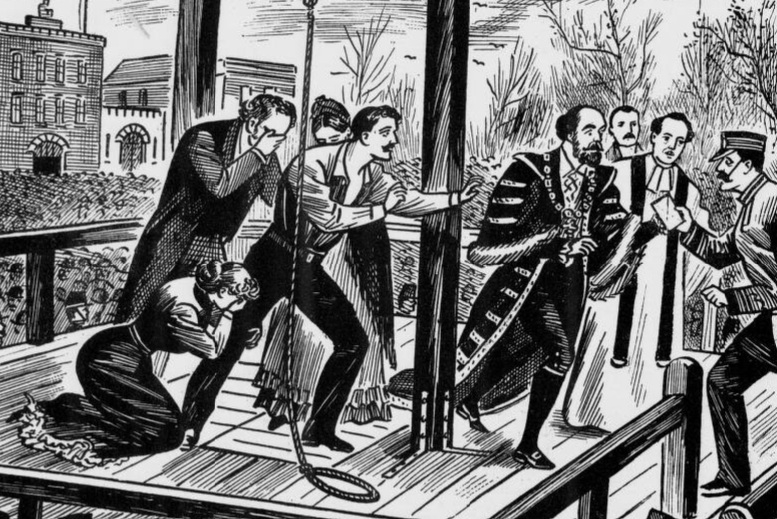

16. A compassionate woman for a condemned man

A slightly more specific wedding superstition comes from another glossy magazine, namely The Graphic. The piece from 22 October 1892 describes how ‘in England there existed, even so late as the eighteenth century, a superstitious belief that a man condemned to be hanged could escape that undesirable fate, provided some compassionate woman came forward at the foot of the gallows, and expressed her willingness to marry him.’

According to the diary of lawyer John Manningham (1570s-1622), the woman would need to wear ‘her smock only, and a white wand in her hand’ as she begged for the hand of the condemned man in marriage. We’re not sure of the legalities of this (could such an action reverse the verdict?), and indeed the practicalities (did the condemned man need to be single?) but given Manningham was a lawyer, we’ll take his word for it.

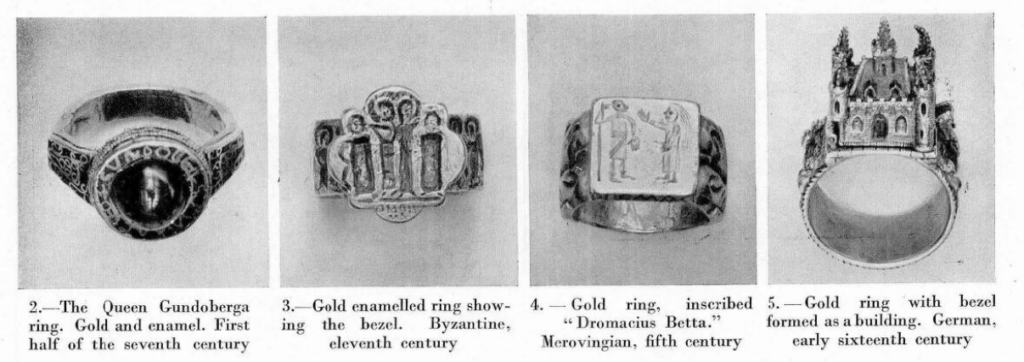

17. Rings as talismans

In November 1924 Bassett Digby, writing for The Sphere, described some ‘more superstitions for women,’ focussing on the ‘talismanic’ power of rings. For example, in the 1800s it was believed that a ring could ‘cure fits if it was made from five 6d.- pieces collected from five bachelors and taken, by a bachelor, to an unmarried silversmith, but only if the donors were unaware of the object for which they were given.’ Again, another very specific superstition!

It was, however, a superstition that was reflected elsewhere in the country. In Berkshire, if a ring was made ‘from a silver coin that had formed part of the offertory at a Communion service, particularly if it had been put in the plate on Easter Sunday,’ it too was thought to cure fits.

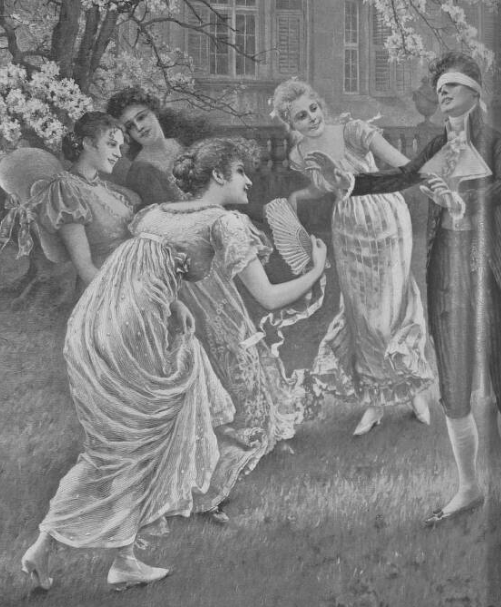

18. Crossing the road: blindfolded

This superstition is a little more location specific, and we learn about it thanks to an account in the Derry Journal, 28 July 1947. The writer describes how whilst they were on a trip with friends to Ballyliffin, County Donegal, they passed the ‘old abbey graveyard at Fahan.’ There, the writer’s friend had to slow the car they were travelling to a stop, as they watched a girl, with a friend, moving slowly across the road ‘towards the graveyard wall.’

Things got a little stranger, as both her arms were ‘stretched out’ wide in front of her and her eyes were closed. The writer was then reminded of ‘an age-old superstition,’ which ran as follows:

On the right-hand side of the gate, built into the wall, is a stone, and in the centre of it a hole just large enough to hold a person’s hand. The belief is that, if anyone can walk from the other side of the road, blindfolded or with eyes closed, and put one’s hand into that hole at the first attempt, the enterprise on which he or she is engaged will be successful, and in the case of a young man or woman that within a year he or she will be married to the lover of his or her choice.

19. Bless you!

We now move on to superstitions around death, and we start with one superstition that was addressed by national paper the Daily Mirror on 10 July 1978.

Short and sweet, the little piece describes how ‘people say ‘God Bless You’ when someone sneezes because of an old superstition.’ It claims that the phrase came into being because ‘it used to be thought that when you sneezed your soul left your body and the swift saying brought it back again.’

20. A broken clock strikes for death

On 19 December 1890 a correspondent of the St James’s Gazette described ‘a curious incident‘ relating to an ‘old superstition,’ which had taken place in his household. One Monday afternoon, his servant had come downstairs in a panic; for whilst she had been making the bed, the bedroom clock, which had been ‘run down for three days,’ had suddenly struck. The servant was very upset, saying it was ‘the surest possible sign of a death.’

Both the letter writer and his wife had never heard of the superstition before, and the young woman explained how:

…everybody knows that it is a sure sign. When my father was drowned, a clock which had been broken for two years all at once began to strike, and in the morning his dead body was found on the beach.

The couple managed to calm her down, but a few days later she received a letter ‘saying that her only remaining uncle was dead.’ Spookily, he had passed away ‘on Monday morning about the time of the clock incident.’

21. Stop the clocks

The association between clocks and death is played out by another ‘old superstition,’ this time covered by the Aberdeen Press and Journal on 6 October 1922. The paper reported on an address given by a Doctor Pearce to the Senate of Cambridge University. Doctor Pearce attested how his watch stopped ‘at the moment his friend, Dr W.H. Rivers died.’

The Aberdeen Press and Journal believed that this link may indeed have given ‘fresh currency to an old superstition, for there was formerly a widespread belief in some affinity between men and timepieces which caused a watch or clock to stop with the stoppage of its owner’s heart.’

Indeed, the paper went further, suggesting a ‘similar affinity…between flowers and human beings,’ with many accounts of ‘plants drooping and dying in sympathy with the illness and death of their owners.’

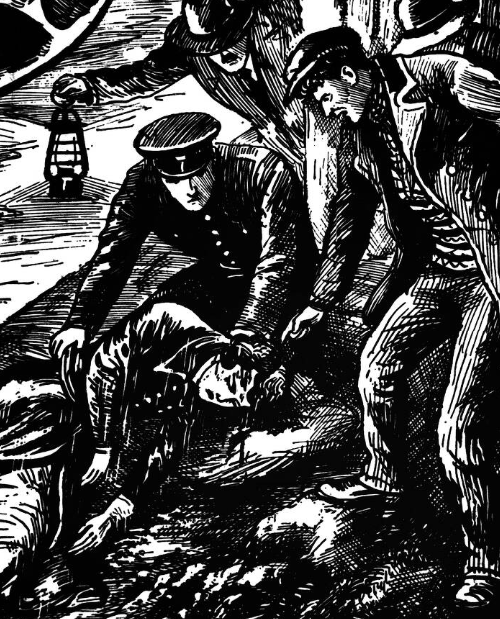

22. Bread and quicksilver

Our next superstition, although apparently niche in its application, was one that we found widely reported across our newspaper collection. This particular account comes from the Fleetwood Chronicle, 6 March 1906, and concerns the inquest on a young woman who had sadly drowned herself in a canal in the Bliston area.

The recovery of her body, as the paper relates, was ‘effected in a singular manner…through application of an old Black Country superstition.’ As it stands, the superstition was tragically successful, as the Fleetwood Chronicle relates:

A loaf of bread loaded with quicksilver was placed in the canal and allowed to float until it stopped, the local belief that it would rest over the body enough to be discovered. Singularly, in this instance, when the loaf ceased to move then police at that particular spot threw in the drags and recovered the corpse.

23. At the crossroads

Meanwhile the Leeds Times on 4 November 1899 reported on a macabre, or what it labelled as ‘singular,’ discovery at Harborne, near Birmingham. This again alludes to lore around suicide, which was only decriminalised in England and Wales in 1961.

Workers at Harborne were ‘engaged in the vicinity of four crossroads excavating the road, when they unearthed the skeleton of a man, with a wooden stake driven through the sternum.’ The Leeds Mercury explained how ‘the skeleton was evidently that of a suicide, who, in accordance with the custom of the old days, had had a stake driven through his heart, and then been buried at the dead of night at the crossroads.’

This burial, which had to take place outside of consecrated ground, was thought to confuse the deceased’s spirit, and the spirit would not be able to return to haunt those who remained behind.

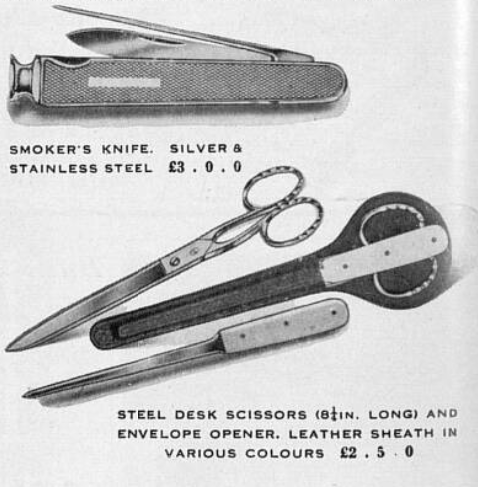

24. Don’t cut the luck

Another of our widely reported historical superstitions involved the giving of ‘a knife or a pair of scissors or anything that cuts’ alongside a halfpenny. The Staffordshire Newsletter, 11 August 1917, describes how the halfpenny should be ‘contributed by way of bringing, and not cutting, the luck.’

But where did this superstition come from? Luckily, the Staffordshire Newsletter was on hand to explain:

This is said to originate from some three centuries ago, when a foreign monarch, in making a present of a sword to a courtier, also made him a gift of money, ‘lest the receiver of the sword might cut himself and so have to seek the aid of a leech or surgeon.’

Therefore, any sort of gift with a sharp point, ‘such as a tie-pin or the pin of a brooch, should be accompanied by a coin.’

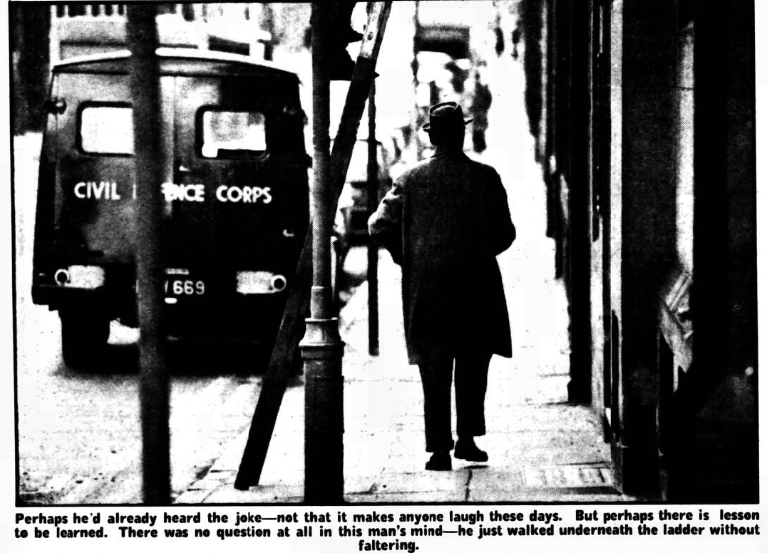

25. Ladders for luck

Our next superstition is one we’re probably all familiar with: ‘one should not pass beneath a ladder,’ in order to avoid bad luck. The Broughty Ferry Guide and Advertiser on 29 December 1934 reported on this ‘old superstition,’ which it rationalised as preventing ‘the danger of something falling on one’s head.’

However, the paper reported on a comic incident, where the obeyance of this superstition very much led to some instantaneous bad luck:

The other day in a Carnoustie street, a window cleaner was engaged at his job on a ladder. A superstitious pedestrian skirted the ladder, but, just as the walker was passing, the window cleaner dropped his sponge, which slid down the rungs of the ladder and hit the nervous pedestrian on the side of the face.

26. Inside out: a lucky mistake

On 4 September 1930 the Ripon Observer reported how ‘quite a few people believe in the old saying that it is lucky to put on any article of clothing inside out, especially stockings.’ The luck, however, ‘only holds goods if you continue to wear the garment that way, and that to change it would be the reverse of lucky.’

But let’s not cheat here, for the Ripon Observer dictates how ‘to put on stockings or any other garment inside out on purpose is not a sign of good luck.’

Where did this old superstition come from? Well, the Ripon Observer dates it back all the way to 1066, to just before the battle of Hastings. As William the Conqueror readied himself ‘for the fray,’ he just ‘happened to put on his coat of mail the wrong way about.’ When his men noticed the mistake, calling it a ‘bad omen,’ the Conqueror replied that ‘on the contrary, it was a good one, meaning that he would be changed from a duke to a king – as, of course, he was.’

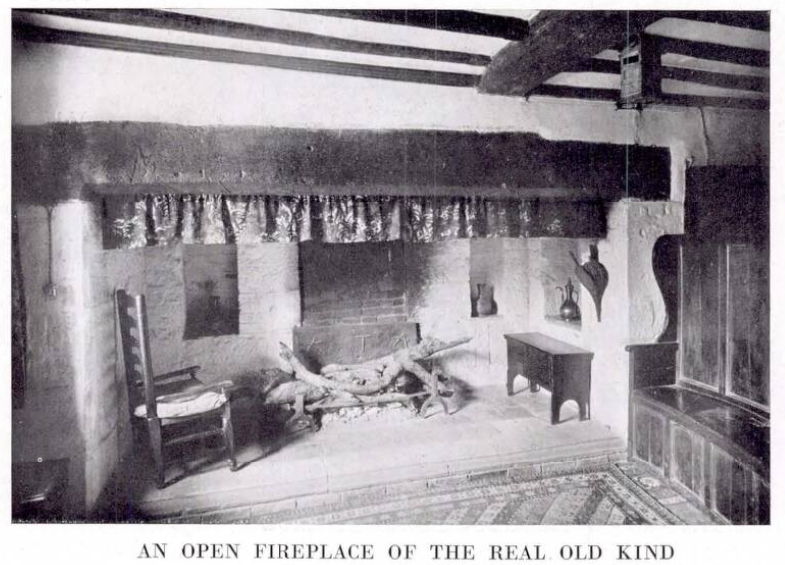

27. A poker for protection

Talking of bad omens, this next superstition was thought to ‘charm’ bad spirits away. On 27 June 1931 the South Bank Express reported on the ‘superstition that a poker placed across the bars of a grate induces the fire to burn.’

As with many of our historical superstitions, this one also has ancient origins, which were expounded by dictionary originator Samuel Johnson. According to the South Bank Express, he believed that ‘the practice arose in the dark ages, through a monkish superstition that the figure of the cross had the effect of driving away evil spirits.’

But what had this to do with a poker? The South Bank Express explains:

As it was supposed that the fire not burning up was due to the presence of the spirits, the form of the cross was made by placing a poker across the bars of the grate in order to charm them away.

And thus, a superstition was born!

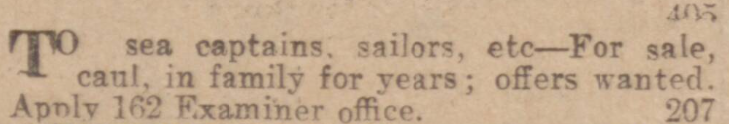

28. Caul for luck

Whilst we mention birth, it’s only appropriate to mention another old superstition, this time which involves the caul, a rare phenomenon where a piece of membrane covers a new-born’s head. In September 1950 a reader wrote to the Edinburgh Evening News asking if a caul was still ‘worth a lot of money if sold to a captain of a ship as a lucky omen.’ The ‘curious’ letter-writer had heard that if a sea captain had a caul in his possession, that his ‘ship will never go down.’

The reply from the ‘News Advice‘ column confirmed old superstitions about the luck-bringing capabilities of the caul. The piece relates how ‘at one time a caul was supposed to indicate great prosperity to the person born with it, and to be an infallible preservative against drowning.’

But was the caul still imbued with monetary value? According to the Edinburgh Evening News, during the nineteenth century sailors would pay ‘from £10 to £30 for a caul,’ quite a sum then. However, the paper believed that ‘nowadays it is highly improbable that a sailor would buy a caul, although there are some who still wear one as a charm.’

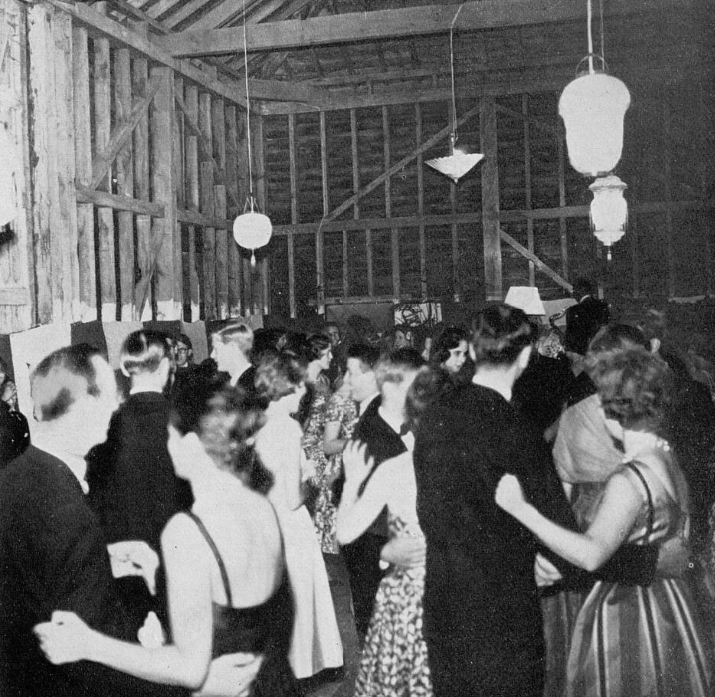

29. A lucky barn dance

We’re off to Northumberland for our penultimate historical superstition of this list. In April 1948 the Shields Daily News reported on the old superstition which said ‘that when a barn is built, country-dancing should take place in it to ensure that the floor holds and that it is satisfactory.’

This old superstition was being adhered to by members of the Youth Hostels Association, who were set to visit Gillespie’s Farm at Old Hartley West, where barn had recently been refloored. The daughter of the farmer, Mary Davison, also a Youth Hosteller, believed that this was ‘an excellent opportunity for hosting a dance.’

30. Red hair and a hot temper

Our final superstition of our list is again a fairly well known one. This superstition was addressed by Ireland’s Saturday Night in June 1936, and it related to the connection between red hair and a ‘hot temper.’

J.E., the writer of the piece, had recently spoken with an old man who ‘confessed that he has never been allowed to forget that he is ‘ginger.” Because the elderly man was never allowed to forget the fact of his hair colour, he became ‘aggressive,’ thus creating the impression he is ‘hot-tempered’ and falsely solidifying the link between red hair and a quickness to anger.

But why the fear of those with auburn hair? J.E. explains that ‘red-haired people are regarded with suspicion in the North, and many rural folks have put down a bad market day to the fact they passed a red-haired woman on the road,’ whilst in the West of Ireland ‘it is an insult to be called a ‘red-haired Dane.’

Meanwhile, J.E. looked beyond Ireland to Scandinavia, where redheads were apparently too ‘regarded with suspicion,’ and to unpopular figures like Helen of Troy and Judas Iscariot, both of whom allegedly had red hair. However, the writer for Ireland’s Saturday Night does not agree with the old superstition; instead, J.E. chooses to highlight a recent study that claimed ‘red-haired students at a university were more brainy than their blonde and brunette companions,’ and the pluck of auburn haired people, who had endured centuries of persecution.

We’ve made it to the end of our list of historical superstitions. Which ones have you heard of? Do you know any more? Head to the pages of our Archive to discover more superstitions, traditions and tales from history today.