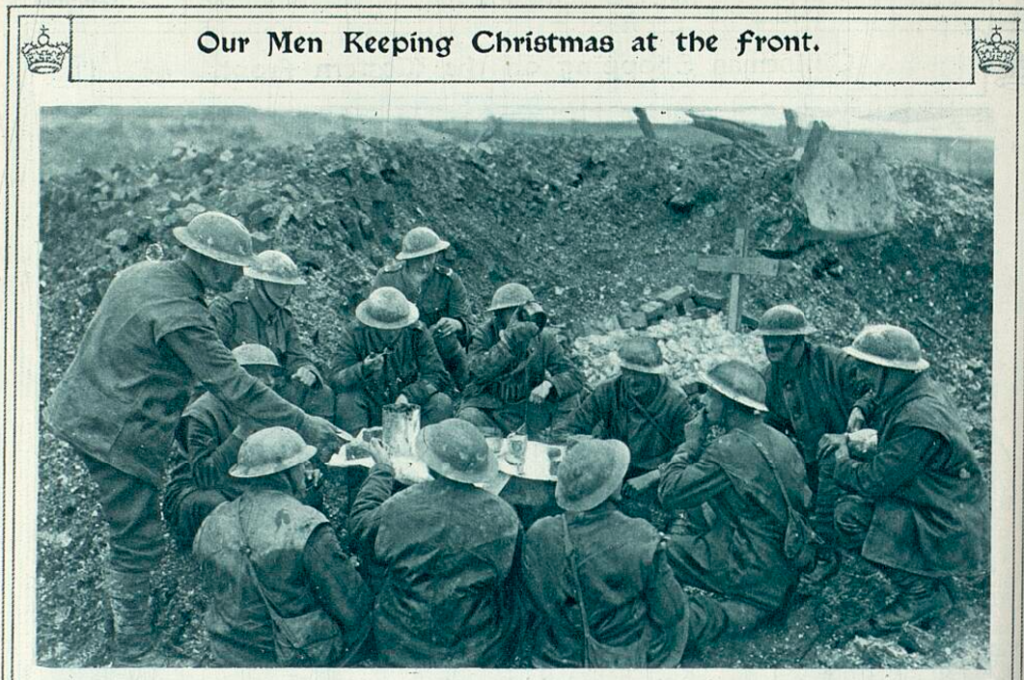

Sent to the front lines, soldiers in the First World War could only communicate home through letters. Although censored, these letters provided comfort to both those at home and those fighting in the trenches, and they were often reproduced by local newspapers.

In this special blog, we’ve pulled out extracts from 30 different letters, sent by servicemen throughout the First World War, which were all featured by our newspapers. These 30 letters, sent by 30 different men, all provide a moving and personal perspective of the war that was meant to end all wars. Expressing a range of emotions: from gratitude for the gift of some socks, to frustration with other men who had not yet volunteered to fight, these letters are important records of the voices the men who left everything behind to fight for king and country.

Register now and explore the Archive

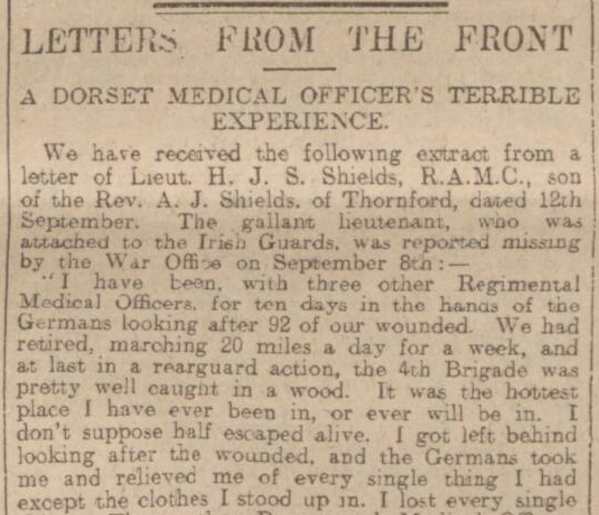

1. Lieutenant H.J.S. Shields, R.A.M.C, to his father, the Reverend A.J. Shields – September 1914

Soldiers’ letters ended up in newspapers usually because friends or relatives receiving the letters would pass them on. Newspapers would then state the provenance of the letter. For example, on 25 September 1914 Somerset newspaper the Western Gazette printed the letter received by the Rev. A.J. Shields from his son, Lieutenant H.J.S. Shields of the Royal Army Medical Corps (R.A.M.C.), who had been ‘attached to the Irish Guards.’

Lieutenant Shields provided a stark account of his provision of medical care whilst taken prisoner by German forces:

I have been with three other Regimental Medical Officers, for ten days in the hands of the Germans looking after 92 of our wounded…I got left behind looking after the wounded, and the Germans took me and relieved me of every single thing I had except the clothes I stood up in. I lost every single thing. Three other Regimental Medical Officers were in the same plight. We were given a house, and got 92 of our wounded in. Many have since died.

The German forces then retreated, leaving Shields and his fellow medical officers to tend to the wounded, and also to find their way back to the Irish Guards.

Lieutenant Hugh John Sladen Shields, having re-joined his unit, was killed in action in late October 1914.

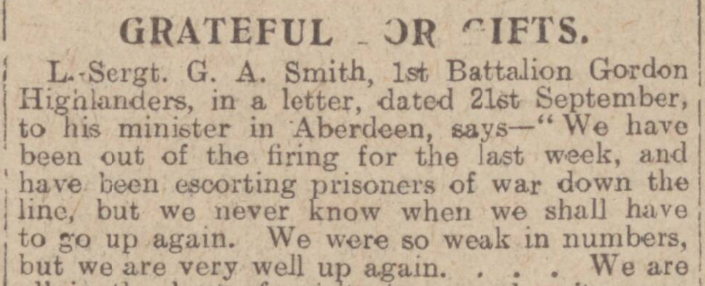

2. Lance Sergeant G.A. Smith, 1st Battalion Gordon Highlanders, to his minister – October 1914

Letters from the front lines were not just exchanged between soldiers and their families, as we shall see. The letter from Lance Sergeant G.A. Smith of the 1st Battalion Gordon Highlanders, which was printed by the Aberdeen Press and Journal on 3 October 1914, was written to his minister in Aberdeen.

Smith tells his minister, who is not named, how he had been ‘out of the firing for the last week,’ escorting prisoners of war. He writes how:

We are all in the best of spirits here, and quite comfortable considering the duty we are on…Plenty of food, as they say it’s the stomach which keeps up the back, and that an army marches on its stomach. We have never wanted. Socks, soap, tobacco, etc., have been arriving from all over Scotland, mainly from our part, which we gladly and thankfully receive from the givers.

Lance Sergeant Smith continues:

It is extremely good of them to think of us at the front, and socks are a thing we need a good supply of. I wish to express our thanks, as I’ve been asked to do so by a few when I said I was writing to a minister, so that you might convey our heartfelt thanks to those who may be patrons to this good cause.

3. Squadron Quartermaster-Sergeant Jack Barber, South Irish Horse, to his father, Mr. J.J. Barber – October 1914

We’ve seen examples so far from Scottish and English troops. Our Irish newspapers, meanwhile, feature letters home from some of the 200,000 Irish soldiers who also fought during the First World War. One of these letters was penned by Squadron Quartermaster-Sergeant Jack Barber of the South Irish Horse, who wrote to his father Mr. J.J. Barber of Fermoy, County Cork.

Barber’s letter, which was written on 28 September 1914, was printed by Cork’s Evening Echo. It runs along cheery lines:

Yes, we have seen a bit of fighting. We were in Landrecies, and things were hot enough for anything and anyone. We retired, but we had the best of the affair. The British losses were very small compared with the Germans. The way our troops behaved that night was enough to make any one proud of being a member of ‘French’s despicable army,’ as our friend the Kaiser called it.

Such missives as Jack Barber’s were undoubtedly a useful propaganda tool in the early months of the war, painting a jolly picture of adventures along the front lines:

I cannot tell you where we are or what we are doing, only that we are going well and very well looked after. Our system of supply is marvellous, and all arms are in splendid condition, very keen, and no sign of any sickness as yet. Weather here is fine, days fairly warm, nights very cold. You might send me a pair wool-lined gloves, and also a pair mittens.

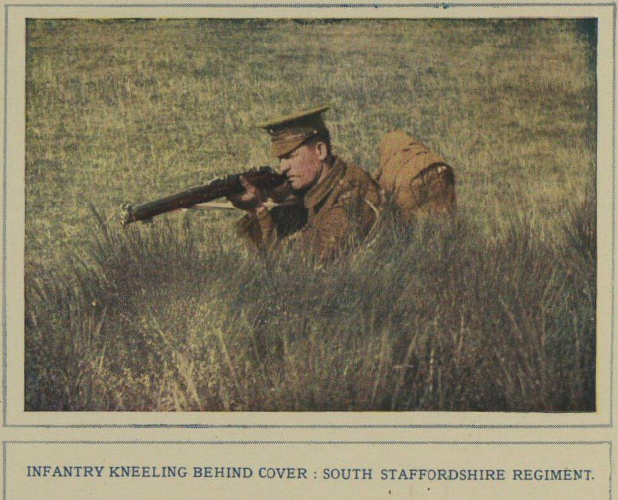

4. Sergeant W. Lilley, South Staffordshire Regiment, to Inspector Thwaite, Millom Police Force – October 1914

Sergeant W. Lilley, previously a police constable in Millom, Cumbria, wrote to his old boss Inspector Thwaite in a similarly cheery, understated, way. His letter was printed by local paper the Millom Gazette on 23 October 1914:

Dear Inspector – Just a line to let you know that I am still in the land of the living, and trust that you are all well. I am pleased to say that I am, up to the present have escaped unhurt, for which I am thankful.

The South Staffordshire Regiment sergeant went on describe his experience near Mons, noting how:

The retreat from Mons was very hard work; we would get to a place where we thought we were to stop and sleep, when suddenly we had to move again, and during the ten minutes’ halt each hour our men were falling asleep. But when we started to advance, everybody was joyful, and singing, as retreating does not suit our men.

The way the letter blends the hardships of the retreat, with the joy of the advance, is an extraordinary testament to the experience of men like Sergeant Lilley during the early months of the First World War.

5. First Class Air Mechanic Jack Hodgson, Naval Flying Corps, to a friend – November 1914

On 3 November 1914 the Hull Daily Mail printed an ‘interesting’ letter on its front page. Penned by First Class Air Mechanic Jack Hodgson of the Naval Flying Corps to a friend, it came not from the land front, but from the frontlines of British naval action.

Hodgson, a Goole native, was serving on the H.M.S. Engadine, and it was new role for him, working in the Naval Flying Corps. He describes in his letter how:

I like the work…which is very important for the safety of the country. I am in the thick of it. If I come through all right I shall have a lot to relate when I come home, which I hope will be for Christmas…How are the Goole boys at Hull (in the Commercial Battalion) getting on? I suspect they will be ready for the front by now. I am sorry to say I never hear from them. What a time we shall have when we all come home.

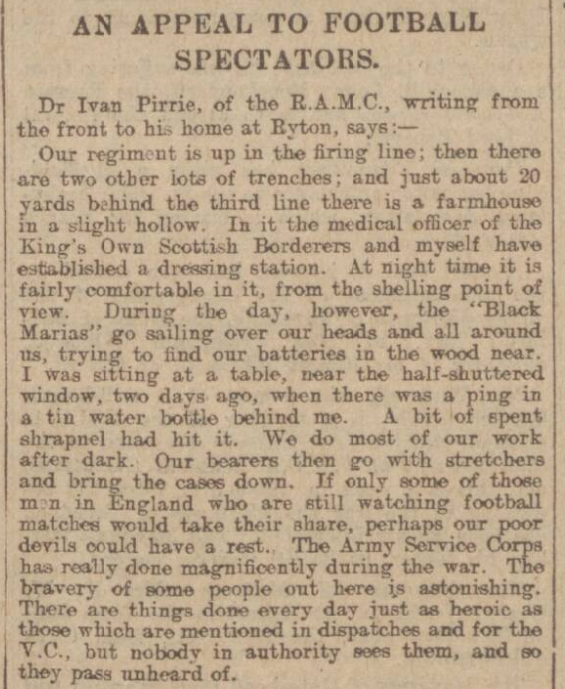

6. Dr. Ivan Pirrie, R.A.M.C., to his home at Ryton, County Durham – November 1914

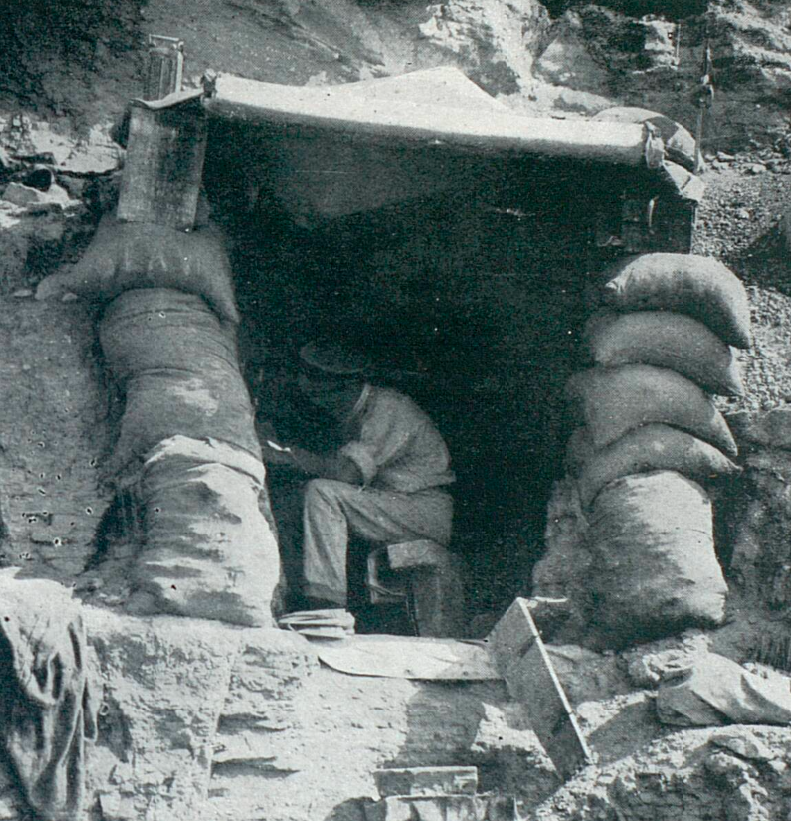

Our next letter comes from another member of the R.A.M.C., Dr. Ivan Pirrie, which was written ‘from the front to his home at Ryton.’ The letter, which was printed by the Newcastle Journal on 21 November 1914, takes on a different tone, as Pirrie describes his experience of being ‘up in the firing line.’ It was here, just behind the lines, that Pirrie and a fellow medical officer had set up a dressing station in a farmhouse:

At night time it is fairly comfortable in it, from a shelling point of view. During the day, however, the ‘Black Marias’ go sailing over our heads and all around us, trying to find our batteries in the wood near. I was sitting at a table, near the half-shuttered window, two days ago, when there was a ping in a tin water bottle behind me. A bit of spent shrapnel had hit it.

Pirrie’s tone then changes, as he moves to address those men who had not yet signed up:

We do most of our work after dark. Our bearers then go with stretchers and bring the cases down. If only some of those men in England who are still watching football matches would take their share, perhaps our poor devils could have a rest.

This entreaty to those back home is a theme that we shall see more and more of in the letters that were sent home from the front.

Dr. Ivan Pirrie survived the conflict, rising to the rank of Major (Acting).

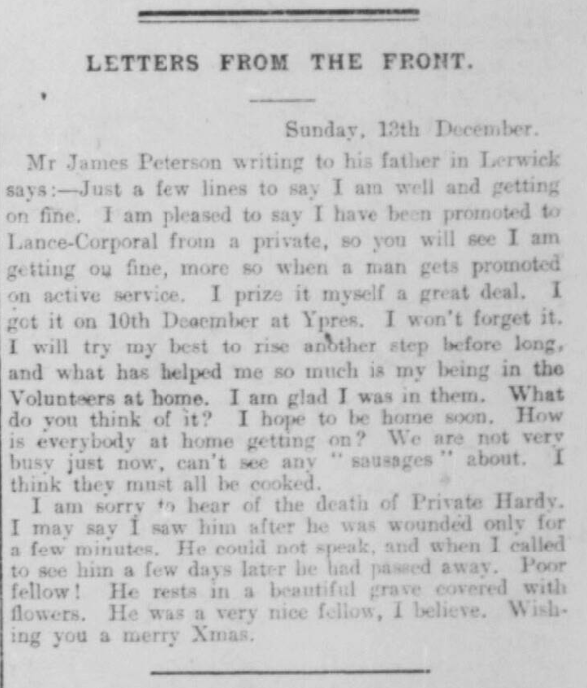

7. Lance-Corporal James Peterson to his father – December 1914

On 12 December 1914 James Peterson wrote to his father in Lerwick, Shetland, with good news. His local newspaper, the Shetland Times, throughout the conflict published letters from the front, and Peterson’s note was one of them:

Just a few lines to say I am well and getting on fine. I am pleased to say I have been promoted to Lance-Corporal from a private, so you will see I am getting on fine, more so when a man gets promoted on active service. I prize it myself a good deal. I got it on 10th December at Ypres. I won’t forget it.

The newly-promoted Peterson, although proud of his advance through the ranks, then went on to express his hope that he would be home ‘soon.’ His letter, meanwhile, ends on a tragic note, as he addresses the death of an acquaintance Private Hardy. It is clear he is trying to soften the blow for his father, as he describes how:

I may say I saw him after he was wounded only for a few minutes. He could not speak, and when I called to see him a few days later he had passed away. Poor fellow! He rests in a beautiful grave covered with flowers. He was a very nice fellow, I believe. Wishing you a merry Xmas.

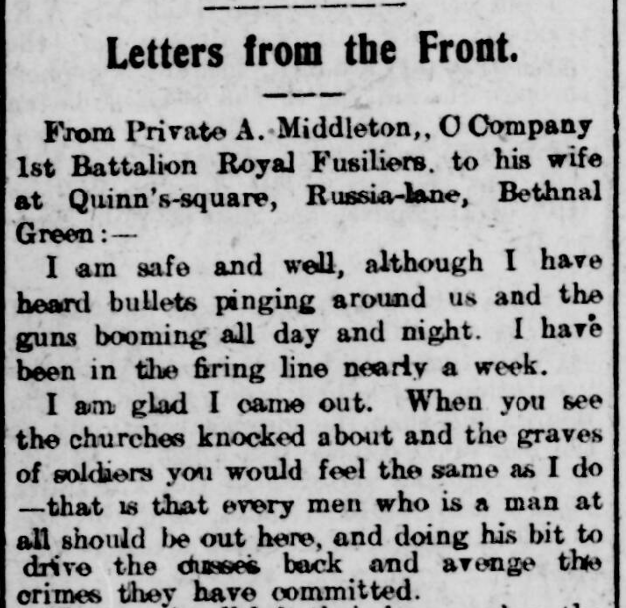

8. Private A. Middleton, C Company 1st Battalion Royal Fusiliers, to his wife – January 1915

As the war was not over by Christmas, as many had hoped, letters continued to arrive from the front. In January 1915 Private A. Middleton of C Company 1st Battalion Royal Fusiliers wrote home to his wife, who lived at Quinn’s Square, Russia Lane in Bethnal Green, East London. His letter was printed by his local paper, the East End News and London Shipping Chronicle, on 12 January 1915.

Middleton’s missive adopts the key points of propaganda put out by the British government, which highlighted the depravity of the German army. All told, he is glad to have his opportunity to fight:

I am safe and well, although I have heard bullets pinging around us and the guns booming all day and night. I have been in the firing line nearly a week. I am glad I came out. When you see the churches knocked about and the graves of soldiers you would feel the same as I do – that is that every man who is a man at all should be out here, and doing his bit to drive the cusses back and avenge the crimes they have committed.

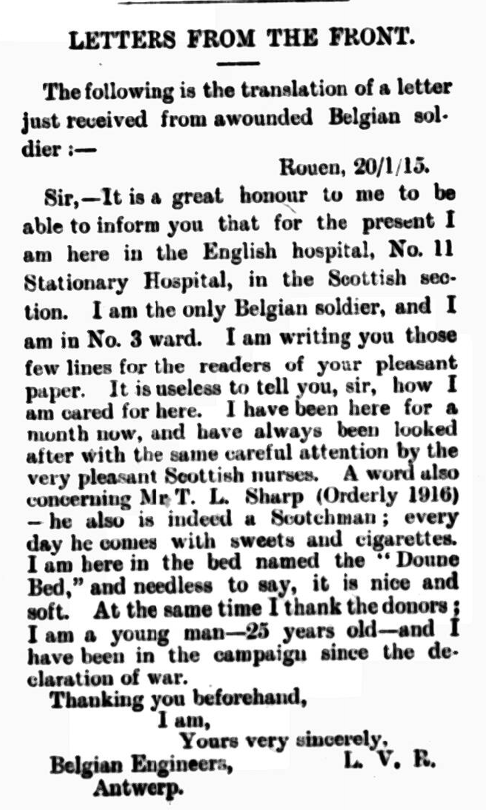

9. L.V.R., Belgian Engineers, to the Devon Valley Tribune – February 1915

Signed only with his initials, L.V.R., a wounded Belgian soldier wrote to the Devon Valley Tribune, a Scottish paper that was published in Tillicoultry, Clackmannanshire. The soldier’s letter, which was published by the newspaper on 2 February 1915, was translated into English:

It is a great honour to me to be able to inform you that for the present I am here in the English hospital, No. 11 Stationary Hospital, in the Scottish section. I am the only Belgian soldier, and I am in No. 3 ward. I am writing you those few lines for the readers of your pleasant paper.

L.V.R., a 25-year-old member of the Belgian Engineers, was greatly pleased with his treatment at the hospital, as he wrote:

It is useless to tell you, sir, how I am cared for here. I have been here for a month now, and have always been looked after with the same careful attention by very pleasant Scottish nurses. A word also concerning Mr T.L. Sharpe (Orderly 1916) – he also is indeed a Scotchman; every day he comes with sweets and cigarettes.

10. Lance-Corporal Gilbert D. Morton, 10th Liverpool Scottish, to an unknown recipient – February 1915

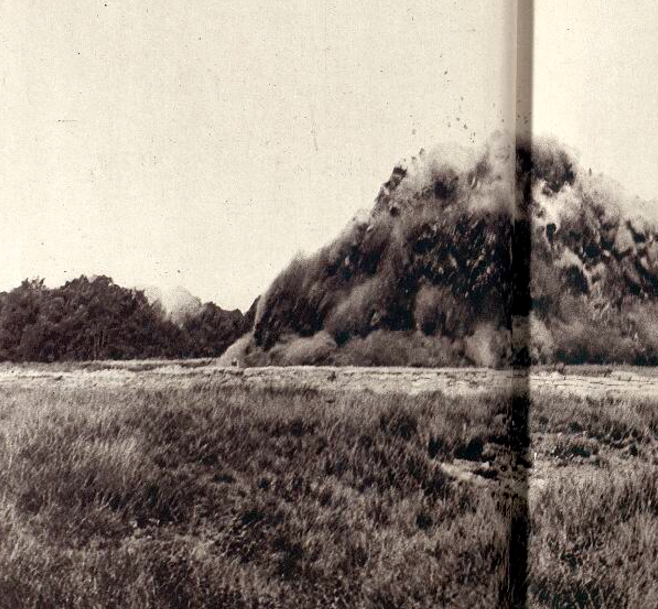

Meanwhile, other letters provided a vivid description of what life was like ‘with shells buzzing over.’ A letter from Lance-Corporal Gilbert D. Morton, 10th Liverpool Scottish, which was dated 28 January 1915 and printed by the Tamworth Herald on 6 February 1915, painted a picture of life on the front line for readers back home:

It was dry all the time we were in the trenches, but this was balanced by the Germans giving us a lively time with their shells. I have never seen such holes in the ground before. They would nearly take a house in. When the shells burst the soil and the splinters of shell are flung up to a height of 60 feet or more, and it comes pattering down on your back like rain, but in big lumps.

One fellow nearly got us. It just dropped about 15 yards behind the part of the trench I was in, shaking the earth. When such shells burst you feel the earth tremble 200 yards away, so you can imagine what it is like to be near them.

Morton’s is a striking account, all the more so for the other details he divulges. Soldiers like him, in the trenches, were ‘without drinking water for 24 hours or more,’ with ‘boiled sweets or acid drops’ being used to quench one’s thirst.

Gilbert Douglas Morton survived the conflict, attaining the rank of Acting Major.

11. Private John Horsley, 1st Battalion Northumberland Fusiliers, to his mother – February 1915

In a letter to his mother, who lived at 9 Melbourne Street, Newcastle, Private John Horsley of the 1st Battalion Northumberland Fusiliers described his own close encounter with a shell. The account was published by the Newcastle Journal on 15 February 1915:

The other day my pal and I were sent to do a bit of work, when suddenly a shell burst close to us, wounding six of our men. I think I was the luckiest man among them, for they were all within five yards of me. I had just turned my back to go down a cellar for a saw when I heard the men groaning and moaning with pain. It was an awful sight, and I will never forget it. I thought my number was up. A small piece of shell struck me on my back, but, fortunately, I was not hurt, and am still alive and kicking.

12. Sergeant Michael Walsh, 2nd Battalion Royal Munster Fusiliers, to a friend in Tralee – February 1915

Other letters from the front went to detail about their experiences. One such letter was penned by Sergeant Michael Walsh of the 2nd Battalion Royal Munster Fusiliers back to a friend in Tralee, County Kerry. Local newspaper the Kerry Reporter printed it on 27 February 1915:

A line to thank you for the cigarettes. You have no idea how grand it is to get something from home. We are just after being relieved out of the trenches after three weeks’ hard fighting at La Basse. The Germans are getting an awful slaughtering there. The last attack they made they lost 900 dead. On our right they were charged by the Coldstream Guards and Irish Guards; it was a terrible sight; we lost 3 killed and 97 wounded.

Walsh continued:

We got off very light considering the heavy rifle and shell fire. We had to bring 74 wounded Germans to the hospital to get dressed; they were Bavarians and Uhlans. I am specially mentioned in despatches with L.C. Daly and Lieut. Carrigan for holding our trenches for two hours with four machine guns, while the company had to retire; we stuck it under heavy shell fire; I am expecting a French military medal for it.

In a letter full of information, Sergeant Walsh was sure to thank ‘Miss McConnell for the cigarettes she sent the Battalion’ as he signed off.

Sergeant Michael Walsh of Tralee was killed in action on 21 August 1916.

13. Private M. Rivett, Lincolnshire Regiment, to his wife – March 1915

As the war went on, soldiers’ letters home began to focus on the tragic loss of life around them. Private M. Rivett’s letter home to his wife in Boston, Lincolnshire, was picked up across the Irish Sea by the Belfast News-Letter, which it published on 26 March 1915:

I am writing these few lines with a sad heart. We have had heavy losses in the battalion. We buried seven of our officers. Captain Wellesley amongst them. I helped to fetch the bodies from the firing line. Even while we were digging the graves the Germans shelled us so heavily that we had to leave them and get into dug-outs for two hours. The Germans suffered terrible losses. It was an awful battle, but we are making great progress. Though our battalion lost heavily in the charge, they did splendidly. They were the leading battalion, and went through the lot.

Martin Rivett survived the First World War, passing away in Lincolnshire in 1974.

14. Private James Taylor, Grenadier Guards, to his sister – March 1915

In the same spread of letters from the front, Private James Taylor of the Grenadier Guards wrote to his sister in Dowsby, Lincolnshire, describing the horrors he had witnessed:

Our battalion lost twelve officers, so you can guess what a hot time we had. I hope I have not got to see anything else half so bad again. Nearly all my pals are either killed or wounded, so I feel rather lonely. The man who gets through can shake hands with himself.

Taylor’s anger at what he had witnessed during battle pours through his lines:

The Germans were glad to give in when we got right up to them with fixed bayonets. I was never in such terrible bloodshed. The big guns going off on both sides are enough to drive a man off his head, to say nothing of tumbling over dead bodies in the dark. We went through two ditches about 5ft. deep in water, and had our clothes on for three days. Some of the men in England don’t know they are born.

15. Private D. McDowell, 2nd Battalion Royal Irish Regiment, to a friend in Banbridge – April 1915

Meanwhile, Private D. McDowell of the 2nd Battalion Royal Irish Regiment, in a letter to a friend in Banbridge, County Down, gave his opinion of his German opponents. He described how, in a letter sent from the ‘firing line’ and published by the Banbridge Chronicle on 24 April 1915:

To tell you the truth the Germans are the greatest cowards in the world. They extensively use hand and rifle grenades, which no doubt are very effective when they explode. The enemy often try and mine our trenches, and on Wednesday last they tried the same game, and after the mine exploded made an attack, but they were sorry for it and for two hours one would have thought the world was at an end. Then came a calm, and at daybreak we found seven hundred of their dead lying in front of our trenches. We only had one killed…

McDowell, however, ends his missive on a humorous note:

If you see any of the dentists tell them to have a good stock of teeth as we will require some when we get home, seeing that the biscuits are made out of ‘concrete.’

16. Corporal J. Philpotts, 1st Royal Warwicks, to his parents – June 1915

Whilst we have covered accounts of shelling and mine attacks, another devastating weapon deployed during the First World War was gas. In a letter to his parents at 56 Clifton Road, Gloucester, from the Mote Hospital at Maidstone, Corporal J. Philpotts described a gas attack. His account was then published on 12 June 1915 by the Gloucester Journal:

We had stood the fearful shelling and the remnants of gas coming to us from the front trench now in these trenches for nearly three hours. The brave lads up in the front were like a stream. First they were driven back by the enemy’s gas, and then when the gas was past and come on down to us they rushed forward and gained the lost ground. Then they were back again, then forward again…There was a continual stream of ‘gassed’ and wounded men struggling by us and always cursing the Huns; never moaning for themselves.

Corporal Philpotts then described how he was injured during the battle:

I myself was acting the ostrich, laid on the ground with my head under cover behind a tree stump. But the rest of my body was exposed. Suddenly something hit me on the right buttock with such force as to turn me over on to my back. I got up and tried to clear out of the way, but my legs gave way, and a fellow Corporal picked me up and rushed me out of danger behind a big mound of earth. Here the stretcher bearers…dressed my wounds.

Find Corporal Philpotts’ medical record after his injury on our sister site, Findmypast.

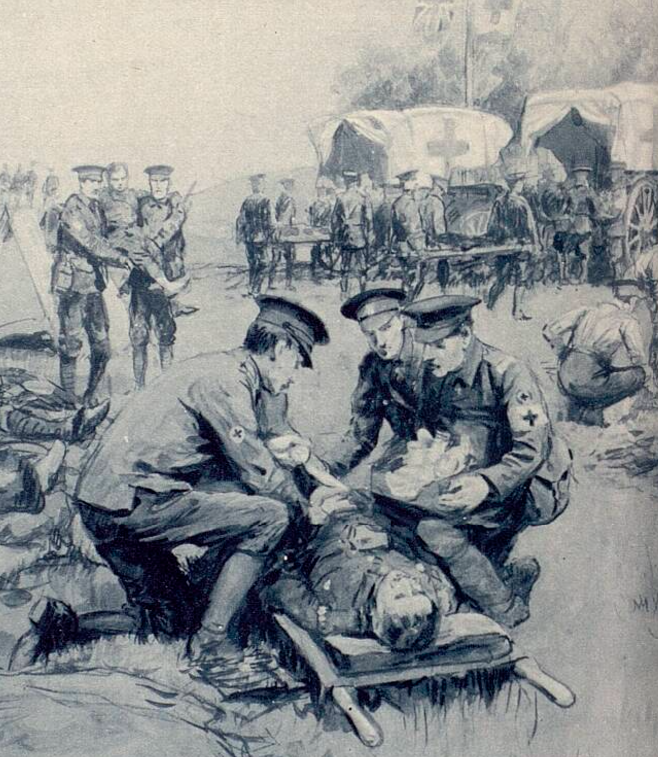

17. Major Arnold Irwin, C Company 5th Battalion Northumberland Fusiliers, to the Reverend T.W. Allen – June 1915

On the same day as Corporal Philpott’s account of getting injured during a gas attack and being rescued by stretcher bearers was printed in the Gloucester Journal, the Newcastle Journal published a letter from Major Arnold Irwin of C Company 5th Battalion Northumberland Fusiliers to the Rev. T.W. Allen. The letter began with thanks to the Reverend Allen, who as vicar of St Luke’s, Wallsend, along with the Men’s Institute, had sent gifts to Irwin’s company, the Wallsend Company.

However, as was the duty of commanding officers during the First World War, Major Irwin sadly reported on the death of Private George Gibson on 24 May 1915:

Gibson was a stretcher-bearer, and it was while carrying out the noble duty of assisting a wounded comrade that he met his death. The trench had been subjected to a violent bombardment, following a severe attack made with gas by the enemy, and a man lay wounded in an exposed position of the trench. Gibson, casting away all thought of his own safety, unflinchingly went to the side of the wounded man and administered what comfort he could under the circumstances. A few minutes later another high explosive shell fell in the same position, mortally wounding the gallant stretcher-bearer and killing the already wounded man. Gibson only lived a few seconds, and, muttering, ‘I am done,’ passed into the great beyond.

Major Irwin ended his letter by praising Private Gibson’s ‘pluck and sacrifice’, noting how his parents lived at 14 Third Street, Wallsend.

18. Corporal W.F. Sercombe, 6th Gloucesters, British Expeditionary Force, writing home – July 1915

Soldiers at the front were granted some respite, as Corporal W.F. Sercombe of the 6th Gloucesters described in his letter home, which was published by the Clevedon Mercury on 10 July 1915. Sercombe outlined how:

We are at present in a chateau, situated in delightful grounds, right out in the country, well away from the firing line, and the change has proved most beneficial to me, short though it may be. I am feeling quite fit and well again – a new man, in fact.

Sercombe, well aware that his time at the chateau was set only to be a short one, made the most of his new surroundings:

Fruit is fairly plentiful here, and I have been able to buy some nice strawberries and cherries. I have also ferreted out a nice little farm, where I can get my food cooked and buy extras, such as eggs, butter, milk &c. which the army rations do not include…it is a great thing to be able to have decent, well-cooked food and to be able to eat it in cleanliness and comfort!

William Frederick Sercombe survived the conflict, attaining the rank of Staff Sergeant.

19. Lance-Corporal H. Pope, 2nd Gloucesters, writing to acknowledge a parcel – July 1915

Meanwhile, other soldiers in their letters from their front took time to write about what was happening at home. This was true of Lance-Corporal H. Pope, a native of Deerhurst, Gloucestershire, and a member of the 2nd Gloucesters. His letter home, which was summarised by the Tewkesbury Register, 17 July 1915, talked extensively about his local town of Tewkesbury:

…it makes the men feel more content to know there are people in Tewkesbury who think about them and send them comforts, which are so much appreciated. He is glad to know that Tewkesbury has done so well in recruiting; every fit man should lend a helping hand, for the more men we get the sooner the war will be over. It should be realised that mufti is not the fashionable wear for this summer.

Again, letters home from the front become an important propaganda tool, in encouraging men to sign up and play their part.

20. Gunner H. Jobson, 1st Peru Battery South African Mounted Rifles, to his parents – August 1915

Letters from the front did not just come from France and Belgium, as this was a global conflict. On 27 August 1915 the Cambridge Independent Press printed a letter from Gunner H. Jobson of the 1st Peru Battery South African Mounted Rifles to his parents, who lived at 2B, Vine Cottages, Haverhill, Suffolk. He related his experiences in Namibia:

I will be on my way back by the time this reaches you. I suppose you heard of the surrender of the Germans here, and that the country is now British. We had a very hard time of it when we were chasing them, and when we got to Otavi they put up a little bit of a fight, but not much, and when they found out they were surrounded they sued for peace; we were pleased when we heard of it.

21. Signaller Leslie James, 9th Battalion of the Welsh Regiment, to his grandfather Mr. Charles James senior – October 1915

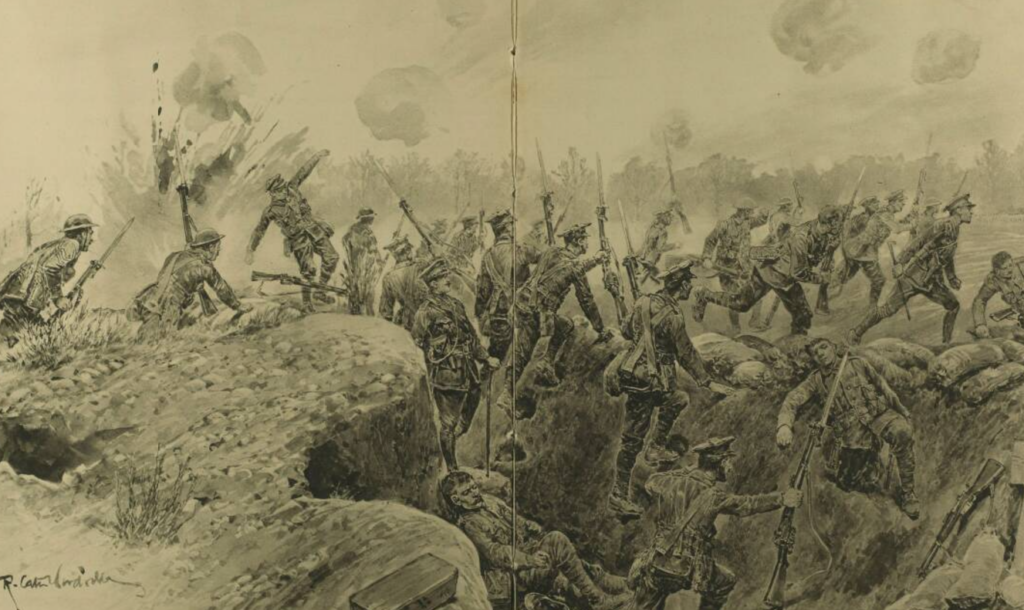

Back now to the Western Front, from where Signaller Leslie James, 9th Battalion of the Welsh Regiment, wrote to his grandfather, Mr. Charles James senior. His long letter was reprinted by the Porthcawl News on 14 October 1915, and it gave a vivid account of going over the top.

Signaller James’s account is almost naively gung go, with the Welsh native describing his ‘excitement’ at the thought of having a ‘smack at those devils who had destroyed the beautiful towns and churches, violated women and girls, killed old men and kiddies, and had done everything possible to fill anyone with disgust.’ As the time drew near to battle, James described how:

Well, the night wore on, and at 6.30 in the morning the boys were all under the parapets waiting for 7 o’clock to come. There was no laughing and chatting now; every man’s face was set and stern, knowing full well that all who went over the parapet would not come back. Some of us surely had to go under, but, Grandpa, there was no shirkers amongst that crowd, every man was a game one, willing, if needs be, to lay down his life for the country he fought for.

At their Colonel’s command, Signaller James and his comrades, ‘like a lot of greyhounds,’ leapt over the parapets, only to met by rapid machine gun fire. However, James assured his grandfather that they ‘gained a great victory,’ as he emerged from the fray ‘without a scratch.’

22. Sydney Dyche, British Army blacksmith, to the Burton Daily Mail – October 1915

It is remarkable how cheery these letters home were given the horrors that these men were witnessing on a daily basis. On 17 October 1915 British Army blacksmith Sydney Dyche wrote to his local paper the Burton Daily Mail in a similarly cheery vein, again pointing to the synergy that existed between the troops of the First World War and their newspapers back home:

Just a line to thank you and your readers of the ‘Burton Daily Mail,’ for the cigarettes I received. I am sure we all appreciate your kindness for the generous gifts you so regularly send to us. I suppose by now you have heard of the gallant charge our lads have achieved. They have proved themselves as good soldiers as there is in the British Army.

Dyche continued:

Sorry to say I have done no fighting yet, as I am a blacksmith on the transport. There is only one more donkey I want to shoe very badly now, and that is the Kaiser. We shall shoe him hot when we catch him.

Sydney Dyche survived the conflict, passing away at the age of 80 in 1965.

23. Corporal D.M. Edwards, Royal Engineers, to Regimental Sergeant Major Fear – January 1916

On 13 January 1916 the Welsh Gazette printed a series of letters penned by some of the ‘brave men who have gone from Aberystwyth’ to the front, ‘in acknowledgement of parcels sent out by’ Regimental Sergeant Major Fear.

One such letter was written by Corporal D.M. Edwards of the Royal Engineers, who was stationed in France. Again, Edwards painted a surprisingly jolly picture of life on the front line, albeit perhaps just for Christmas:

Things were quite jovial here this Christmastide. On Christmas Eve the – Guards took their band with them into the trenches, while next day some fraternising took place. The Germans had a large drum on their parapet. Our artillery, however, soon put an end to it. The Germans even in spite of this continued to sing with great enthusiasm ‘Tipperary.’

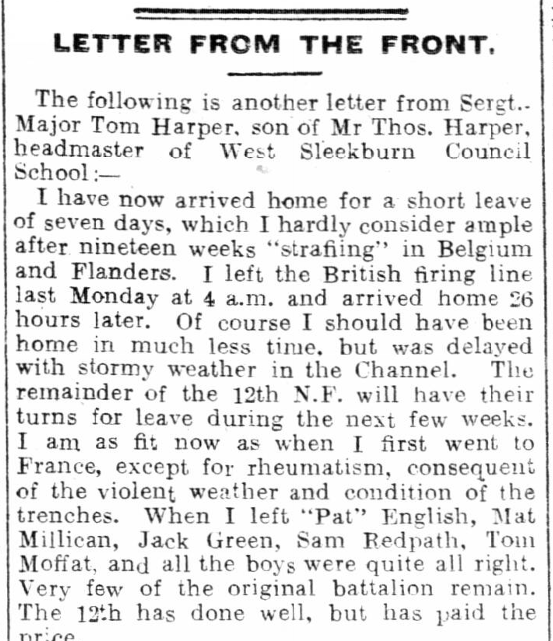

24. Sergeant-Major Tom Harper, 12th Battalion Northumberland Fusiliers, to an unknown recipient – January 1916

Meanwhile on 14 January 1916 Northumberland newspaper the Morpeth Herald printed a ‘letter from the front,’ which was authored by Sergeant-Major Tom Harper, the son of Mr. Thomas Harper, the headmaster of West Sleekburn Council School. This was not a usual letter from the front, however, as Sergeant-Major Harper had just returned home on leave:

I have now arrived home for a short leave of seven days, which I hardly consider ample after nineteen weeks ‘straffing’ in Belgium and Flanders. I left the British firing line last Monday at 4 a.m. and arrived home 26 hours later. Of course I should have been home in much less time, but was delayed with stormy weather in the Channel.

Whatever Harper’s very legitimate gripes about his leave situation, his letter was filled with pride over the men of his battalion, as well as with suspicions about his German opponenents:

Our boys are not content to remain in the trenches – they must be over the parapet. Several times lately they have obtained permission to visit the Huns and bomb them out…About a fortnight ago I had to take four German prisoners from the line to a place a few miles in the rear. They were the typical Hun – close cropped and treacherous. I asked in English, French, Flemish and German if they could speak English. By signs they convinced me they could not. However, after reaching our destination, one of them exclaimed: ‘Is this town Armentieres?’ I had better not tell you of my reply. Flanders is swarming with spies, but our boys know how to deal with them.

Sergeant-Major Harper’s letter ended with a rallying call to those men who may not yet have enlisted, whilst noticing the stark differences between life at the front and life at home:

If there are any likely candidates left in Morpeth and district who would like to wear khaki in place of flannels this summer, tell them to do so now, and help us to wipe the Prussian off the earth – then to return home and partake of the welcome which awaits the brave lads.

25. Private S. Tebbutt, Leicester Pioneers, to his old teacher Mr. W. Buckby – May 1916

Other letters from the front were imbued with a touching sense of naivety, such as the one written by Private S. Tebbutt of the Leicester Pioneers to his old teacher, Mr. W. Buckby. Even though the war had been going on for nearly two years, men who were not used to warfare, especially after the Military Service Act in January 1916 introduced conscription, were arriving in the trenches and having to adjust to life there.

Private Tebbutt’s short letter was printed by the Leicester Evening Mail on 1 May 1916:

This is the first time I have been able to write to you. I am in the best of health. I have not seen as yet any of the old Sunday scholars or your son. We do not get many luxuries out here. Wishing you the best of luck and that we shall have a safe return.

26. Private T. Maines to the Newton and Earlestown Guardian – May 1916

Meanwhile, one Private T. Maines was a regular correspondent to his local newspaper, Lancashire’s Newton and Earlestown Guardian. The paper printed one of his letters on 19 May 1916, as Maines wished to let his friends know that he was in Armentieres with his battalion. Maines goes into great detail about his duties, which involved, ‘every other night,’ fixing ‘the wire in no man’s land.’

Maines records how:

Just before our lot came out of the trenches – on the night of the 30th – I went out wiring in the front. The Germans must have seen us with the powerful searchlights they use, for our covering party say they saw them trying to flank us and cut us off. All the party were running for their lives when I caught sight of them, so I went with the rest, and a good many of us got hung on the barbed wire. I was in a nice state; one or two nearly got drowned in the stream.

Thankfully, none of his comrades ‘got hit on this occasion,’ although there had been many wounded since.

Maines signs off his letter rather wistfully, writing:

I have not much time for any more news, so will close, trusting the war won’t last much longer, and hoping to be with my friends in the near future, for I have just had my name taken for a furlough. So good-bye to all my chums in Earlestown for the present.

27. Private P. Birkett, Royal Irish Fusiliers, to an unknown recipient – June 1916

Private P. Birkett of the Royal Irish Fusiliers, in a letter that was summarised by the Galway Observer on 24 June 1916, also hoped to be ‘soon coming home on furlough.’ Private P. Birkett, who was ‘well known’ in Galway, had just been through a gas attack along with his regiment.

Meanwhile, Birkett’s letter home gave him an opportunity to express his Irish pride:

The good old Faughs, he writes, stuck undaunted to there [sic] guns, pouring on the enemy a most deadly fire. The gas having passed by our lines the Huns took the opportunity of attacking us, but the Irish blood in us showed itself to the fullest, we met them with a concentrated fire from our guns. Nothing but fleeing Germans in all directions, who were cut down by our artillery and machine guns, the accuracy of our aim being worthy of all pride.

28. Sergeant Jim Parke, Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers, to his parents – July 1916

Meanwhile, Sergeant Jim Parke of the Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers became one of the many thousands of men who were wounded during the First World War. To that end, he wrote not from the front lines to his parents in Moville, County Donegal, but from a hospital in Liverpool.

His letter was printed by the Londonderry Sentinel on 18 July 1916:

I got my wounds just as I got to the German front line on the morning of the advance. I see the Ulster Division is getting great praise for the way they went into action. They deserve it all. We had a very stiff part of the Hun line to attack. His machine gunfire swept the ground we had to cross like hail, but, in spite of it, we got across and drove the Hun out, taking lots of prisoners and guns. If we are able to keep him on the go, now that his frontal position has been taken, he won’t stick it very long. Anyhow, we’re going to win.

James Parke was killed in action on 16 August 1917 and is remembered at the Tyne Cot Memorial in Belgium.

29. Second-Lieutenant Wilfred Stanford, British Expeditionary Force, to an unknown recipient – November 1917

We move into 1917 now, with a letter that was printed by the Halesworth Times and East Suffolk Advertiser on 27 November 1917. The letter was penned by Second-Lieutenant Wilfred Stanford of the British Expeditionary Force, which detailed a ‘very rotten experience’ that he had recently endured.

Stanford described his very close call, or what he described as ‘quite the narrowest squeak,’ relating how:

I was coming from our front line to Company H.Q., and had two men in front of me and three men behind me. A shell came along and landed about two or three yards away. The result was the man just in front of me was heard to call out Oh! and has never been seen or heard of since.

Second-Lieutenant Stanford continued:

My servant, who has hanging on to my coattails, was wounded, and the man in rear of him had some of his fingers blown off. I heard the shell coming and seemed to have some sort of intuition that it was coming near, so immediately flopped down flat in the mud and slush, the result being that I got off scot free except for a blow in the middle of my back.

30. Sapper S. Thomas, Royal Engineers, to the Porthcawl News – August 1918

From 1917 now to August 1918, and the last few months of the war, comes the last of our 30 letters from the front. Taking the time to write to his local paper, the Porthcawl News, from ‘somewhere in France,’ was Sapper S. Thomas. Still that link between local newspapers and soldiers at the front endured, even well into 1918.

Sapper Thomas’s letter runs as follows:

Having a little time to spare after being heavily engaged in action, I take this opportunity to write you a few lines. I sincerely hope that all at Porthcawl are enjoying good health. I received the ‘Porthcawl News’ week by week. I notice that a good number of local lads have been home on furlough. We all appreciate the ‘Porthcawl News’ out here in France, and look forward to its arrival each week. It brings back memories of happy days at dear old Porthcawl. Everything points to a victorious end of the war for Britain and her Allies.

It is appropriate to end with this letter, which highlights the important role that newspapers had in keeping up the morale of those serving on the front, bringing an important sense of home and comfort into a hellish world of bombardment by shells and gas attacks. Newspapers themselves, meanwhile, provide an important record of the experience of those many thousands of men who were sent out to fight during the First World War, many of whom never come home. These letters are an important memorial in themselves to those who sacrificed their lives whilst in service of their country, and you can find many more of them in the pages of our newspaper Archive.