This month at the British Newspaper Archive we are celebrating all things pet related – and what better way to start than by taking a special look at some of the bravest cats and dogs that we have found in the pages of our newspapers?

From the role that dogs played on the European front during the First World War, and interwar domestic heroism, to the introduction of the Dickin Medal in 1943, in this special blog we will explore some of the moving stories which involve some of the bravest cats and dogs in history.

Top tip: keep your search terms general. Even searching for just ‘dog’ or ‘cat’ can return some fascinating results.

Watch out for our blog next week – where we take a look at the bravery of our feathered friends – namely the pigeons who played such a vitally important role in both World Wars.

Register now and explore The Archive

First World War – ‘These Canine Allies’

When Germany invaded Belgium in the August of 1914, dogs played an important role both in the evacuation of civilians and also military manoeuvres. Illustrated journal The Sketch notes how ‘even women, children and dogs are drawn into the great whirlwind of war.’ Pictured in its pages are dogs drawing barrows for their refugee owners, taking them to some kind of safety. Dogs were also employed to draw the ‘quick-firing guns’ of the Belgian Field Force, as ‘In Belgium, dogs, of large and powerful breed are largely used for draft purposes.’

And dogs – so called ‘canine allies’ – were put to use by other nations during the First World War. The Sphere in 1915 pictures the kennels that had been ‘specially constructed by the French Army authorities in the French lines.’ These kennels were home to five different breeds of sheepdog (Malinois, Gronendael, Bas Rouge, Briard and Berger Allemand), who had originally been employed solely for ‘ambulance work.’ But ‘owing to their great intelligence it was found possible to use them for taking back messages from advanced parties to the rear.’

Dog kennels on the French front | The Sphere | 25 December 1915

The Sphere goes on to describe how ‘the dogs are quite happy and interested in these novel surroundings and are in the best of condition.’ Meanwhile, the German army were also using dogs, ‘for ambulance work in connection with the Red Cross.’ These brave animals had been specially trained to locate wounded soldiers, and when found, they were trained not to bark but instead to ‘return and fetch their masters.’

Consequently, dogs on both sides of the conflict in the First World War played a vital humanitarian role, helping to preserve and save human life.

Hero Dogs at Crufts 1932 – ‘Courage and Fidelity’

In 1932, fifteen brave dogs were on show at the ultimate dog show, Crufts. These dogs had been specially selected by the Daily Mirror, who awarded the Silver Gugmunc Collar to animals who ‘risked their lives to save human beings.’ And these dogs, featured in a spread in The Sketch, were particularly special – only twenty-three collars had been given out since the reward’s inauguration, demonstrating the immense bravery of dogs in a domestic setting.

Alongside the dogs at Crufts sat tales of their ‘exploits, so that visitors could see the ‘heroes’ in person and read of their courage and fidelity.’ Take, for example, Gyp of Streatham, who had rescued three children from a tent when it caught fire, rushing in and dragging away their bedclothes, so that the children awoke and escaped.

Brave Chum of Southsea | The Sketch | 17 February 1932

Chum of Southsea also saved his mistress from a fire by rousing her – losing an eye and falling unconscious in the process. Nip too, of Ilford, saved his master and mistress from a fire. Meanwhile, Jack from Davenport flung himself on ‘blazing clothes’ to extinguish himself a fire – badly burning himself in the process, but he thankfully made a full recovery.

Nip of Ilford | The Sketch | 17 February 1932

Some of the brave dogs on show had saved their human counterparts from attacks by other animals. Pedro of Cumbernauld attacked an ‘infuriated horse and thus saved the life of a youth it was about to savage.’ Teddy of Pembrokeshire saved his master’s daughter from an attack by a sow, who had knocked her down and was crushing her. Moffat Treasure from Harlseden showed immense skill and courage when he brought a runaway horse to a standstill, by ‘seizing [its] reins in his teeth.’

Moffat Treasure of Harlseden | The Sketch | 17 February 1932

Meanwhile other dogs saved humans from drowning. Another Pedro, this time from Sheffield, ‘plunged into the River Dee when it was in full spate and saved a girl of sixteen from drowning.’ Moss of Ystradgynlais performed a similar exploit when he ‘sprang from a high rock into the River Tawe and saved a boy from death from drowning.’ Peggy, from Wigan, saved a boy from drowning in a canal, whilst Prince of East Grinstead held onto a girl named Hilda’s ear when she fell into a pond, as he barked for help. Peter from Letheringsett, Norfolk, likewise held the arm of a little girl when she fell into the water until help arrived.

Peter, who saved a little girl from drowning | The Sketch | 17 February 1932

Blitzed Pets

On the outbreak of the Second World War, the pets of Britain faced a new kind of threat – the Blitz. Aerial bombardment not only had its human victims, but its animal victims too, as well as its animal and human heroes.

A ‘sad-eyed’ victim of air raids in the South East of England | The Sphere | 9 November 1940

The Sphere pictures one ‘pathetic victim of the air raids.’ This poor hound had been ‘picked up by the RSPC, whose Blue Cross ambulances are constantly on the watch for such cases in bombed areas.’ Another victim of the air raids was a dog who was discovered by the Pioneer Corps after having being buried for three days in bomb wreckage. Happily, after being given a meal, the dog made a full recovery.

The Sphere also introduces us to Spot, who had been discovered by the Pioneers in a bombed-out house in London’s East End. The Pioneers soon found that they had gained a new pet, as Spot refused ‘to leave the Pioneer friends who saved his life.’

And pets during the Blitz were also responsible for saving life. As reported in the Illustrated London News, Beauty, a six-year-old wire-haired fox-terrier was presented with the Dickin Medal for ‘saving sixty-three animals trapped by Blitz debris and also some humans.’

Beauty receives the Dickin Medal | Illustrated London News | 20 January 1945

The Dickin Medal, known as the animal’s equivalent of the Victoria Cross, was introduced by Maria Dickin, founder of the People’s Dispensary for Sick Animals (PDSA), in 1943. Aiming to honour brave animals of wartime, it is inscribed with the words ‘For Valour’ and ‘We Also Serve.’

Two Alsatians, Irma and Jet, were similarly honoured for their brave rescue exploits during the Blitz, as was Rip of Poplar, who, according to the Illustrated London News, scented out ‘twenty-seven trapped air-raid victims.’

Rip of Poplar | Illustrated London News | 15 September 1945

There were also some brave cats who survived the Blitz. The Liverpool Echo describes the bravery of Faith, the church cat of St Augustine’s, Watling Street. ‘She guarded her kitten through a night of terror in a blasted and burning house during the Battle of London.’ Faith, ineligible for the Dickin Medal as she was a ‘civilian cat’ instead received a silver medal from the PDSA.

Rob the Parachute Dog and Other World War Two Heroes

Whilst pets on the home front were exhibiting great bravery, pets in various theatres of war were doing the same. One famous military pet was Rob the Parachute Dog. The Illustrated London News tells us that he was ‘a war mascot of twenty parachute jumps, with [a] Blue Cross medal for service in North Africa and Italy.’

Rob the Parachute Dog | Illustrated London News | 15 September 1945

In 1952, seven years later, the Illustrated London News relates the news of Rob’s sad death at the age of fourteen. Rob had also been awarded the Dickin Medal for ‘outstanding service during the war.’

A contemporary of Rob was the Alsatian Antis. The Illustration London News describes how Antis, who was an RAF Squadron mascot, ‘was wounded, and saved life on several occasions.’ Antis had been founded abandoned as puppy in a deserted château during the Battle of France, and promptly adopted.

Antis the Alsatian | Illustrated London News | 26 March 1949

Simon the Ship’s Cat

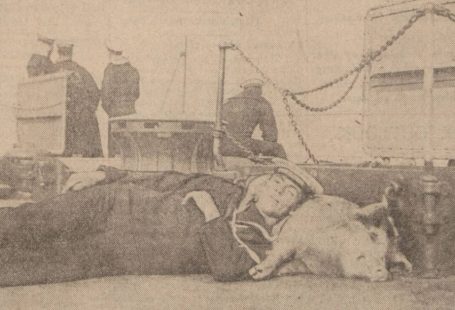

In 1949, HMS Amethyst was sailing along the Yangtze from Shanghai to Nanjing, when she was fired upon by the People’s Liberation Army. Stuck for several months, this event became known as the Amethyst Incident or the Yangtze Incident, and it produced an unlikely hero – Simon the Ship’s Cat.

Simon the Ship’s Cat, as reported in the Liverpool Echo, became the ‘first cat to hold the Dickin Medal,’ and it was also the first time that the award had gone to the Royal Navy. Simon had received four wounds when the HMS Amethyst had been under fire from artillery. The Western Morning News goes onto detail further examples of Simon’s bravery, for he had caught rats, thus protecting vital food supplies, even whilst wounded.

Simon the Ship’s Cat | Aberdeen Press and Journal | 30 November 1949

According to the Liverpool Echo, a ‘piece of the Dickin Medal ribbon has been forward to Simon.’ This was in the August of 1949; tragically, in November 1949, the Aberdeen Press and Journal carries the sad news of Simon’s passing.

Placed in quarantine in Hackbridge, Essex, Simon fell ill. Despite the best care from the Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons, Simon passed away. The Aberdeen Press and Journal speculates whether ‘his wounds in the Yangtse River exploit may have been more serious than expected,’ but goes on to explain that it was ‘gastritis [which] struck him down.’ Simon actually hailed from China, and therefore, ‘the rigours of the British climate may have accomplished what shot and shell failed to do.’

Western Morning News | 14 April 1950

In April 1950, a memorial in Plymouth was unveiled in Simon’s honour, as reported in the Western Morning News. Alderman W Harry Taylor explained how Simon ‘set an example not only in the animal world, but to human beings also.’ Also at the ceremony was local landowner the Earl of Mount Edgcumbe, president of the Plymouth PDSA, who commented how ‘Simon was a very junior but very important member of the crew:’

The Earl said he could not help thinking that the poor cat, having lost his ship, friends, and liberty, felt there was not much worth living for, and died of a broken heart.

Commander of the HMS Amethyst, Lieutenant Geoffrey Weston, who unveiled the memorial, took a more practical view of the tragic passing, commenting that ‘Simon died from the combined effect of his wounds and germs, and was, no doubt, sorry to lose his shipmates.’

Simon’s final resting place | Illustrated London News | 6 August 1955

What is under no doubt is the role that Simon played ‘in maintaining the high level of morale of the ship’s company.’ Simon was interred at the PDSA’s Cemetery at Ilford, Essex, alongside other winners of the Dickin Medal, who had helped to save both animal and human life both at home and abroad.