As Christmas is once more upon us, and the world slowly starts to go back to normal after several years of lockdowns, Christmas parties are again back in vogue. It got us wondering here at The Archive how the Christmas party has changed and developed over time. Naturally, we turned to our newspapers to discover more, learning how the key components of food, drink and music have always been part of historic Christmas celebrations.

So in this special blog, we will look at Christmas parties through the ages. We will take a glimpse, through our newspapers, of what Christmas parties looked like in medieval times, whilst stopping by some eighteenth and nineteenth celebrations, to end with a model 1930s Christmas party.

Register now and explore the Archive

‘Religion and Gluttony’

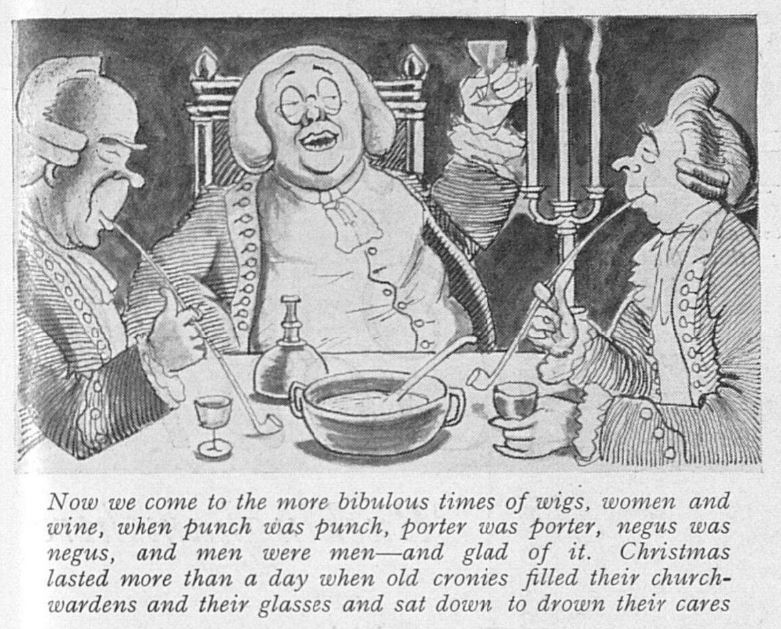

For our first stop, we searched out eighteenth century newspapers for mentions of a Christmas party. We came across a piece authored by a ‘Member of the Church of England,’ which was featured in the Caledonian Mercury on 1 January 1791 addressing ‘Christmas and New Year.’

He begins by writing how ‘the mixture of religion and gluttony, of piety and punch-making, which takes place at this season, has often been a matter of serious consideration.’ The clergyman highlights the feasting and the drinking that occurred to mark the Christmas season, noting how ‘the scene of dissipation generally commences at Christmas, and continues without the smallest intermission till several weeks after New Year’s Day, which has, time out of mind, been ever famous for feasting and rioting.’

Indeed, he berates his contemporaries for their excessive drinking, describing how they are liable to ‘drink whole bottles and bowls of punch, and wine, and brandy, and the devil himself only knows what, until we can neither speak, stand, or see.’ He also notes the excessive consumption of food at Christmas time, with revellers being offered ‘dishes…so numerous, that we know not half their names.’

What is clear from his remarks is the strong association between food and drink and the Christmas party. It is a time for excess, for feasting, as well as for religion. But our clergyman has some advice for those taking to the table at Christmas time, penning how:

In the first place, I would advise all citizens, who are said to be fond of eating, not to sit down to table as if it were the last they were ever to see; not to consider the turkies and the chine, the house-lamb and the fish, as so many things, which it is absolutely necessary they should devour.

He continues:

There is not precept in Scripture which enjoins great eating, nor is there any act of Parliament to this effect, at least none that I am acquainted with. To a robust, well-built healthy citizen, I allow two pounds and three ounces of solids, and to those more delicate citizens, commonly called be-milliners, I allow a leg and a wing of a turkey, two cuts of a chine, a plate of cod’s head, besides a proportional quantity of soup, mince-pies, &c.

Meanwhile, he enjoins ‘all bucks, bloods, or choice spirits, to restrict themselves to a moderate quantity of liquor,’ which, in his opinion, amounted to ‘two bottles of punch or port.’

And what else was the hallmark of the eighteenth century Christmas party? Dancing, of course. For example, this advertisement for a Christmas ball appeared in the Reading Mercury on 18 December 1797:

The Nobility and Gentry are respectfully acquainted, that the CHRISTMAS BALL will be held at the GUILD HALL, on Tuesday the 26th of December.

‘Old Hospitality, Old Wine, Old Ale’

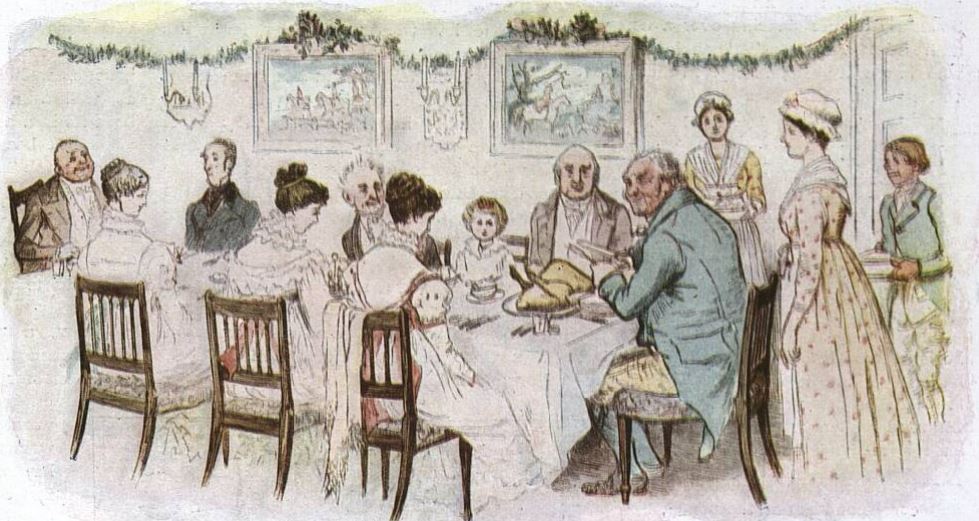

Such themes of feasting and drinking were to continue into the nineteenth century. And the nineteenth century brought with it a desire to encapsulate traditional ways of celebrating Christmas, with hosts looking back into the past for their inspiration.

This is evidenced in an article from The Sphere in December 1957, with glorious illustrations by William McLaren, which describes ‘The Christmas Party at Chainmail Hall.’ This Christmas party had been conjured over one hundred years before by Thomas Love Peacock in his 1831 gothic novel Crochet Castle, in which the host, Mr. Chainmail, presents Christmas festivities ‘in the twelfth century manner.’

The food is the lynchpin of Mr. Chainmail’s celebrations, The Sphere describing how:

The dishes were brought in grand procession. The boar’s head, garnished with rosemary, with a citron in its mouth led the van. Then came the tureens of plum porridge, then a series of turkeys, and in the midst of them, an enormous sausage which it required two men to carry. Then came geese and capons, tongues and hams, the ancient glory of the Christmas pie, a gigantic plum pudding, a pyramid of minced pies, and baron of beef bringing up the rear.

One will note how the food was not exactly authentic for the twelfth century, turkeys having been introduced to England some four hundred years later, but it is feast none the less.

It’s also interesting to note who Mr. Chainmail includes in his celebrations. His guests are not limited to his friends, but incorporate his ‘neighbours, tenants, and domestics.’ This type of Christmas party is democratic, but essentially feudal, encapsulating in the great hall everybody associated with Mr. Chainmail’s estate. Everybody is attendance to enjoy the ‘old hospitality, old wine, old ale.’

And after the feast came music and dancing. Mr. Chainmail’s daughter Susan, the ‘young lady of the manor,’ played a twelfth century song on her harp. After this followed ‘rustic’ dancing, and, of course, more alcohol. This is how the night concluded:

The eccentric party continued long after the ladies had retired and ended in the small hours, ‘the vaulted roof was echoing to a mellifluous concert of noses, from the clarinet of the waiting boy at one end of the hall, to the double bass of the Reverend Doctor at the other.’

‘Revival of Old Christmas Gambols’

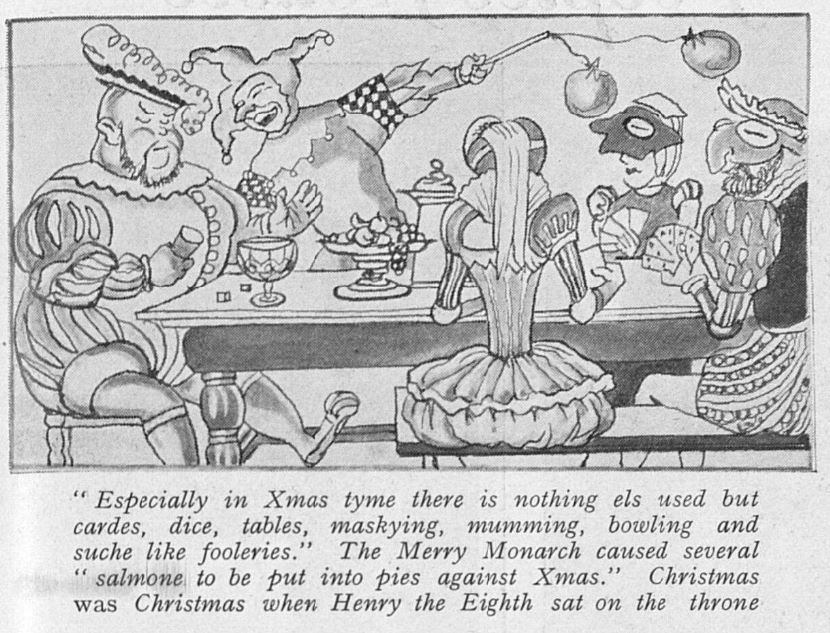

As already mentioned, Christmas parties in the nineteenth century offered an opportunity to look back, and celebrate past traditions. In January 1849 the Illustrated London News reported on the ‘Revival of Old Christmas Gambols’ at Manchester. The festivities were thrown by the Directors of the Manchester Mechanics’ Institution at the Free Trade Hall, and featured all the ‘pageantry, picturesque and grotesque; its revel rout, and roystering; its mirth and mummings’ of ‘Christmas in the Olden Time.’

Forming an essential part of this traditional Christmas party was dancing. A Morris dance was ‘performed by about twenty rustics, decked with ribbons, bells, sashes, and other badges,’ as well as a ‘sword dance.’ The sword dance ‘still lingered as a Christmas custom in the counties of Northumberland and Durham, [and] was given by a number of youths in appropriate attire, decorated with ribbons of the gayest hues.’

After the ‘Presentation of the Boar’s Head,’ a tradition you can find out more about here,’ a ‘the ancient Christmas play of ‘St. George and the Dragon’ was performed by a group of mummers.

Meanwhile, in December 1897 the Belfast News-Letter delved deeper into the past to look at ‘Some Royal Christmas Dinner Parties’ of centuries ago, beginning with one held by Richard II in Westminster Hall. Feasting again forms the ultimate part of such a celebration, Richard II’s ‘most royal feast’ featuring ’28 oxen and 300 sheep, and fowls without number.’

Even Henry VII, who is noted by the newspaper as being ‘not much given to hospitality,’ gave a great Christmas party in ‘the ninth Christmas of his reign.’ He sat down, alongside his Queen and the Court, to a table bedecked with ‘120 dishes…and an abundance of wine.’

Christmas Music

But beyond kings and feasts, what were Christmas parties looking like in ordinary homes? Christmas parties by the early twentieth century had come to the parlour, where music continued to be an important part of celebrations.

Indeed, The Sphere in November 1906 notes how ‘Christmas indeed wouldn’t be Christmas without music.’ It celebrates the ‘quaint old hymns’ like ‘Good King Wenceslas’ and ‘God Rest You Merry Gentlemen,’ but bemoans how in ‘many homes last year…Christmas was but a dull affair’ due to a lack of music.

In a clever example of the early advertorial The Sphere offers up the recently invented ‘Autopiano’ to solve this problem. But this piece also shows how Christmas parties were now being given on a smaller scale, they had come inside, away from the feudal great halls, into the homes of the middle classes, who could entertain their guests comfortably within their own homes.

It is also worth dwelling a little on the ‘Autopiano,’ an invention that did not appear to catch on. The Sphere describes how:

The manner in which the ‘Autopiano’ accomplishes the making a pianist of everyone is by means of an interior, hidden, pneumatic action, which, on the insertion of a small music roll, does all the purely mechanical work of playing the keys. But it is the user who directs the time and expression, by means of a couple of a small levers and stops. Thus a composition, however difficult and intricate it may be, can be rendered with the utmost delicacy and feeling, for the performer is in absolute control, the ‘Autopiano’ following the player’s slightest impulse or desire.

The ‘Autopiano’ could be purchased from Messrs. Kastner & Co., and although ‘intrinsically much more valuable’ than a ‘high-grade piano,’ it cost about the same.

‘Christmas in the Trenches’

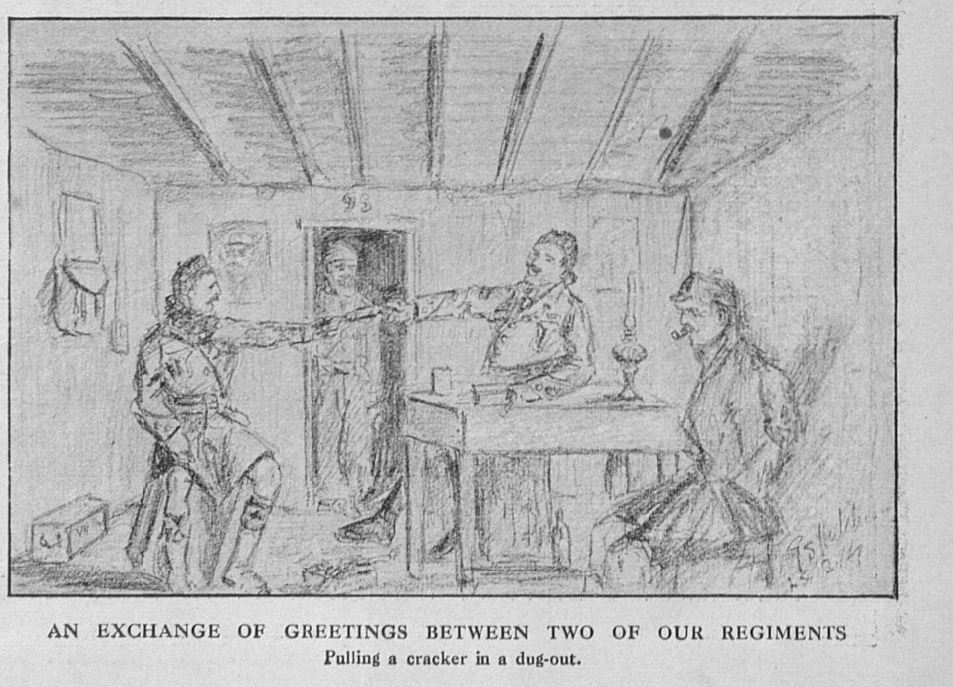

But the advent of the First World War would change the nature of Christmas celebrations, as evidenced by our newspapers. And perhaps the most famous of all the celebrations of Christmas during this conflict came on 24 December 1914, four months after hostilities had begun, in what was known as the ‘Christmas truce.’

The Graphic on 9 December 1915 reported how ‘from all quarters of line in Flanders comes the news that our soldiers and the Germans fraternised freely on Christmas Eve.’ The publication contained a first-hand account of the truce, reportedly witnessed by a ‘Rifleman:’

A party of our men (writes a Rifleman) got out from the trenches and invited the Germans to meet them half-way and talk. And there in the searchlight they stood, Englishman and German, chatting and smoking cigarettes together midway between the lines. A rousing cheer went up from friend and foe alike.

Music marked and created a common ground for both sides, the Rifleman continuing his account:

Presently we heard a cheery ‘Good-night. A Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year to you all,’ with which the parties returned to their respective trenches. After this we remained the whole night through, singing with the enemy song for song. ‘Give us Tipperary,’ they cried. Whereupon adjacent Irish regiment let loose a tremendous ‘Whoop,’ and complied with the request in a way such as only Irishmen can.

The remarkable truce continued on into Christmas Day:

On Christmas Day itself there was another interchange of visits, and occasion was seized to bury the dead of both armies. This business over, we tuned to our conversation. At first we were rather chary about talking or chumming up, but after a while everyone seemed to know everybody else, and we laughed and joked and strolled about in a way that would have startled you good people at home in England.

Christmas, for these men, and for their families back home, would be forever changed by the conflict.

In December 1915 a ‘wit’ writing for The Tatler bemoaned how ‘instead of making merry and making love’ during the Christmas season, they would ‘making munitions.’ However, there was not a complete lack of making merry, as Christmas continued to bring the unlikeliest of people together during wartime.

For example, The Sphere in December 1917 describes a Christmas party given for ‘wounded soldiers by London school children.’ ‘A large number of soldiers were entertained’ by children from Hackney Wick, who performed a ‘Christmas Dream Dance.’ The photographs capture the men looking on in gentle amusement, the children no doubt providing some distraction from the harsh realities of their injuries.

The 1930s Christmas Party

Twelve years after the First World War ended Phillida for the Daily Mirror gave her advice on throwing the perfect Christmas party. By now, the Christmas party had downsized, something to be given in the comfort of one’s own home.

Writing in the Daily Mirror on 29 November 1930, on the eve of Christmas party season, Phillida gives as her first ‘golden rule’ to invite ‘only the people whom you like.’ She writes how:

Do not let your Christmas party be a painful Family Gathering, with The Parents on either side of the fireplace, and the lesser Aunts sitting with their cheaper presents on the outer circle. Exclusively family gatherings at Christmas are out of date. They are a survival of the days when transport was difficult. Families met only once a year and put themselves out to do so. The lesser aunts and uncles came by long and arduous ways, but now if we want to see them we can them in less time than it takes to send a Christmas card.

Christmas parties were being downsized. You should invite ‘only those whom you love, whether it be your old nurse, your mother-in-law, your oldest friends, or the new and attractive ones you hardly know at all.’

But how to entertain your guests? Phillida notes how ‘children are the best entertainment at Christmas,’ but laments how they cannot be kept up ‘indefinitely.’ Music is an option, although she advises how you cannot ‘decently play a new record more than five times.’ Cocktails should be served, and presents given out. After dinner, there should be ‘ghost stories in the dark round the fire for the benefit of the elderlies,’ with hot punch and hot chestnuts being consumed. Even the slick art deco background of 1930, the old Christmas party traditions prevail.

And after the stories and the punch the dancing should commence. Phillida recommends giving a prize to the ‘best couple.’ Finally, she concludes by offering some advice to the Christmas party hostess:

Remember that your part in the festivities will be small. All that you will be expected to do is wind the gramophone, pass the food and drink, go on producing presents from nowhere, laugh heartily when there are spilling and breakings, and take care not to appear better-looking or better-dressed than any of your women guests. This is how perfect hostesses are made.

Conclusion

Ample food and ample drink are never far away from the Christmas parties of the 1700s, 1800s and 1900s, and well before that time. These centuries are all marked by a yearning for past traditions, for the ancient customs of Christmas that provide comfort and cheer. Even round the fireside in the 1930s aural histories prevail, in the custom of Norse and other old tales. Christmas, although Christian in its intent, represents a chance for connection with earthier, older, pagan, traditions, and ultimately, and the parties held during the season represent an opportunity for togetherness. Togetherness that might have at once been a whole feudal community, togetherness that saw enemies come across no-man’s land to mark the occasion, togetherness that has perhaps now diluted to individual families. But the Christmas party celebrates togetherness nonetheless, and an opportunity for celebration not witnessed at any other time of the year.

For more on the history of the Christmas party, and a look at historic Christmas party food and games, follow our social media accounts, and watch out for more special Christmas party blogs this December.