With a history that winds all the way back to Anglo-Saxon and medieval farming practices, the story of allotments in the United Kingdom is as rich as the soil itself. From the General Enclosure Act of 1845, which aimed to give the landless poor an area to cultivate, to the ‘Dig for Victory’ campaign in the 1940s, all the way to the allotment renaissance of the 1990s, we will explore the history of allotments, using newspapers sourced from our Archive.

Register now and explore the Archive

‘Something Always to Do’

Our modern understanding of allotments stretches back to the early Victorian period. Allotments were viewed by some in this period as a way of alleviating poverty, evidenced by an article entitled ‘Allotments for Cultivation by the Poor,’ which was published by the Taunton Courier and Western Advertiser in December 1842.

This piece stridently declared how ‘what is wanted by the poor of this country is labour – constant employment – something always to do – not charity.’ Faced with the spectre of the workhouse, the Taunton Courier describes the ‘thousands and tens of thousands of able-bodied willing labourers in this country now, who look forward to the approaching winter without the least prospect of being able to support themselves through it.’

The solution? Work, but not any kind of work, work upon allotments, which, as the Taunton Courier explained, had ‘already shown itself of great importance to the poor, and beneficial to the landlord.’

1845 General Enclosure Act

Such sentiments were put into political action by the General Enclosure Act of 1845, which made provision for field gardens to be worked by the landless poor. This marked the birth of allotments as we know them, whilst the Essex Standard in December 1847 provided an example of how the early allotments system could work.

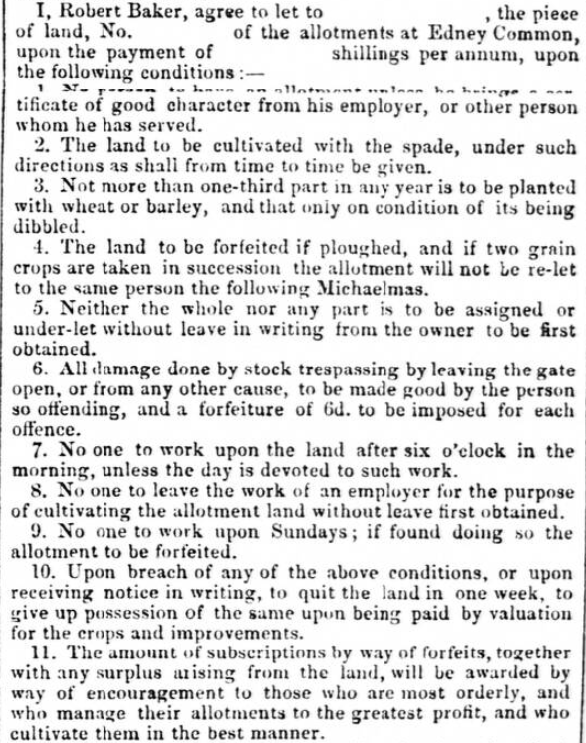

The example came courtesy of Mr. Robert Baker of Writtle, who ‘published the following form of agreement between himself and the poor to whom he lets allotments.’ Robert Baker’s allotments numbered around one hundred, whilst the agreement between him and his tenants ran to eleven points, as show in the below image.

Renting an allotment from Baker was no mean feat. Striking amongst his stipulations were that the person intending to let an allotment be of ‘good character,’ with a certificate to prove it, and that no one was ‘to work upon the land after six o’clock in the morning, unless the day is devoted to such work.’ In other words, those with an allotment could not combine their working day with working on the allotment, surely a challenging balance for those faced with difficult financial circumstances.

Meanwhile, true to the spirit of capitalism that was thinly veiled in the 1842 Taunton Courier piece, Baker’s ‘most orderly tenants, and [those] who manage their allotments to the greatest profit’ would receive extra funds. Charity, wherefore art thou now?

‘Proclaimed a Failure’

However, the allotment system failed to gain traction, even with the passing of further acts in the 1880s, including the Board of Agriculture Act: Enclosure of Commons and Allotments. Illustrated weekly magazine The Graphic in October 1889 noted how although the act was ‘an excellent measure in itself, and warmly welcomed by the farm labourers,’ it was ‘already proclaimed a failure.’

The piece lauded the idea behind the act, describing:

What is the purpose of the Act? Unquestionably to ‘root the peasant in the soil,’ or, in less figurative language, to secure for him a bit of ground, reasonably fertile, conveniently situated and moderately rented, where he and his family might turn their leisure to profitable account – a thoroughly practical aim, there being an abundance of such land throughout the kingdom.

However, the act fell down with those who held the power, The Graphic relating how ‘where the Act fails is in leaving too much power in the hands of the local authorities.’ Furthermore, it was highlighted how ‘farmers are not sympathetic to allotments.’ Even allotment holders themselves were criticised for giving themselves ‘airs of independence.’

Was the giving out of land to the less fortunate too much of a threat to the status quo at this time? A dangerous redistribution of wealth in an era where new labour movements were gaining momentum?

‘A Plea for the Rural Labourer’

However, by the 1890s support for the allotment system was growing, and the cultivation of allotments approached the cultural mainstream.

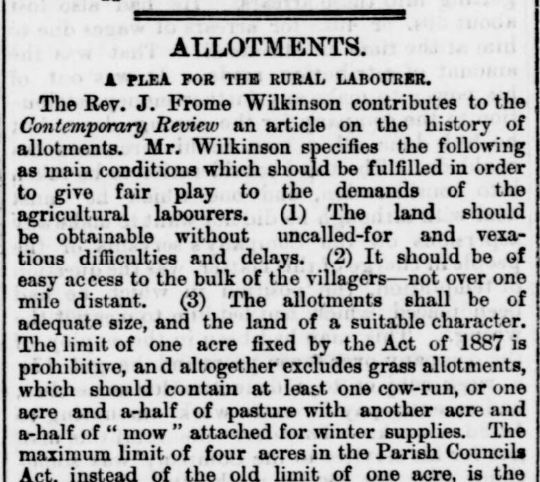

In May 1894 the Dover Express published a piece entitled ‘A Plea for the Rural Labourer,’ which describes the Reverend J. Frome Wilkinson’s work on the history of allotments. Wilkinson positioned himself as an advocate of ‘agricultural labourers,’ outlining the specifications necessary to make the allotment system a success:

1) The land should be obtainable without uncalled-for and vexatious delays. 2) It should be of easy access to the bulk of the villagers – not over one mile distant. 3) The allotments shall be of adequate size, and the land of suitable character.

Wilkinson decried the limitations of the 1880s act, which stipulated a ‘limit of one acre.’ This limit was to the exclusion of grass allotments, which allowed for the keeping of a cow. Indeed, Wilkinson went on to suggest something quite revolutionary for its time:

In other words, not the artificial creation of a peasant proprietary, but the gradual nationalisation of the land by means of a State tenancy, the fee-simple of the land purchased by local authorities remaining in the hands of such public bodies. This process must be facilitated by radical reforms in English land laws.

Allotments!

Wilkinson was supported in his views by Liberal M.P. and physician Sir Walter Foster. In October 1896 the Thetford & Watton Times reported on Foster’s ‘new agricultural formula.’ Instead of ‘the old three acres and a cow,’ Foster proposed ‘an acre and cottage’ for every labourer, suggesting that ‘Parish Councils should have the power to acquire land for building as well as for farming.’

Moreover, this article looked at the failure of allotment schemes in the past, pinning the blame on the Tory party. Indeed, the newspaper shockingly reveals how ’emigration was actually suggested at one time as an alternative to allotments – or, as someone once said, instead of three acres and a cow, three square miles and a kangaroo.’

Allotments, however, were here to stay, as evidenced by their increased mention within our papers. For example, under the excited heading of ‘Allotments! Allotments‘ the Maidenhead Advertiser in February 1895 advertised allotments for the ‘working men of Bray parish,’ whilst the Bucks Advertiser & Aylesbury News introduced on 11 May 1895 what would become a newspaper staple: advice for the allotment holder.

This new column outlined how ‘as Parish Councils have now power to provide allotments for working men, I purpose, with your permission, to discuss in this column points of interest which may arise.’ The Bucks Advertiser & Aylesbury News, therefore, provided advice on how to combat slugs attacking carrots and onions (with soot and lime, or even with paraffin), as well as updates on the obtaining of more land to use for allotments.

‘Phenomena of War’

As the 20th century progressed, and war broke out in August 1914, allotments came into their own. Selkirk’s Southern Reporter, towards the end of the conflict in March 1918, noted how:

The history of allotments in Scotland during 1917 was one of the phenomena of the war. There were something like 30,000 allotments throughout the length and breadth of the country, and that number was being largely added to. The movement had come to stay.

The article quoted then Secretary for Scotland Robert Munro as saying ‘every stroke of the spade was a blow struck against Germany, and every hour spent upon an allotment was of direct assistance to the State.’

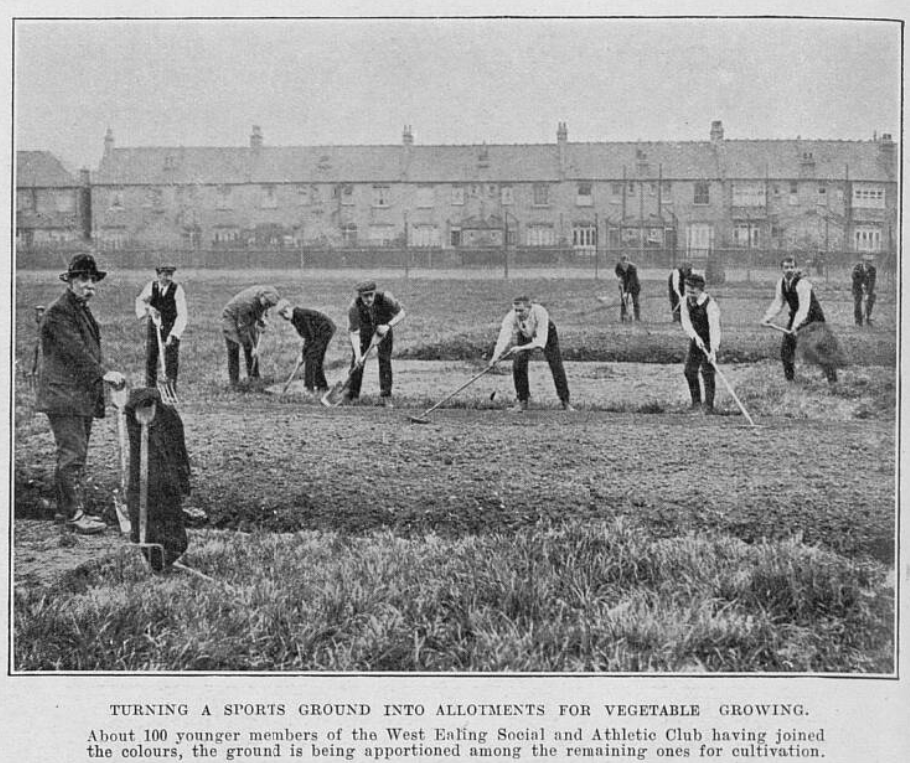

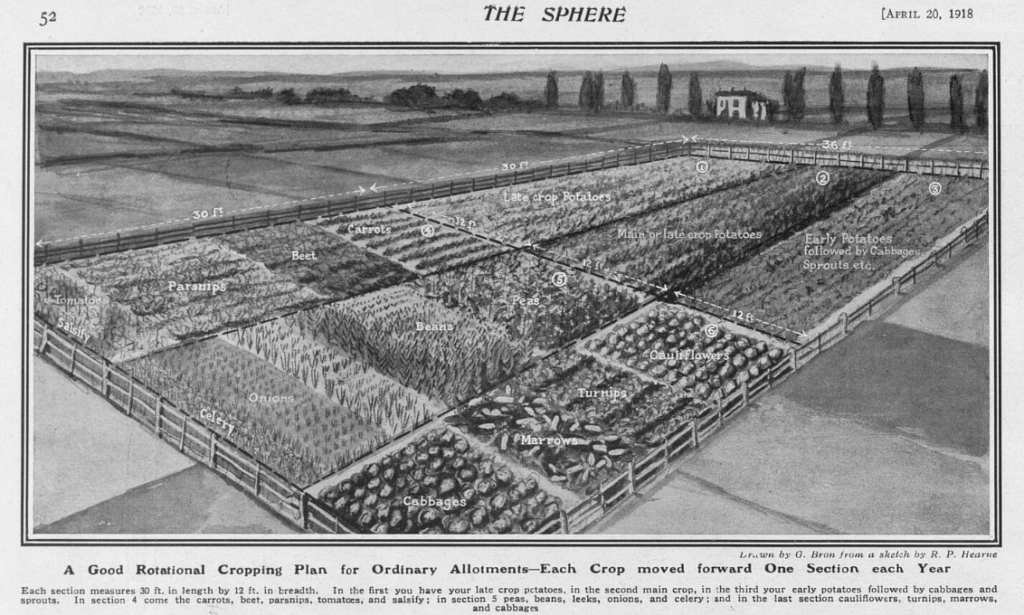

Meanwhile, weekly magazine The Sphere in April 1918 described how ‘few movements created by the war give greater promise of public good than the development of allotment cultivation.’ It gave the total number of allotments in the country as over 212,000, with 10,500 applications in place for allotment plots. Furthermore, The Sphere looked to provide an estimate for the value of the food produced by the allotment system, giving the conservative estimate that allotments across the UK were able to produce ‘not far short of 100,000 tons this year,’ with a ‘market value [of] well over £1,000,000.’

Indeed, national newspaper the Daily Mirror suggested an embarrassment of riches in August 1917, with allotment holders producing ‘more vegetables than they want.’ It described the ‘tens of thousands of industrious and patriotic plotholders all over the country,’ who were faced with a surplus of produce, which caused one allotment ‘enthusiast’ to suggest ‘some sort of co-operative scheme in each district by which allotment holders could meet and exchange or dispose of their surplus vegetables.’

On the Allotments

So as long as the working of allotments supported the war effort, allotments were in favour. And with allotments being worked by thousands across the country, our newspapers were flooded with practical advice for allotment holders, often under the heading, as we saw with our 1890s example, ‘On the Allotments.’

The Aberdeen Evening Express on 23 May 1918 paints a lush picture in its own ‘On the Allotments‘ column, as the piece describes how ‘everywhere the allotments are looking well,’ with ‘young plants [being] fresh and vigorous.’ This column provided advice on the sewing of peas, as well as encouraging allotment holders to ‘sew a little parsley,’ which could then be used during the winter months. Meanwhile, allotment holders were advised to ‘keep an outlook for the ordinary potato disease or blight,’ and to add soot to their plots to ‘destroy slugs and other enemies of germinating seeds.’

Elsewhere, the Liverpool Echo had its own ‘expert’ on hand to provide advice to its readers. On 27 July 1918 this Liverpudlian expert advised how:

Few crops pay better for good cultivation than the onions. Before sowing dig deeply and work in a generous supply of manure…Unlike most vegetables, the onion can stand being grown for successive years in the same plot, provided always the crop is free from vermin or disease.

Another cost-effective food stuff, according to the Liverpool Echo, was the leek, which was described as being ‘nourishing and easily cooked in a variety of ways’ and so ‘a first-rate crop for the small-grower.’

Allotment Protest

The First World War had provided an important lesson in allotments. J.R. Clynes, in a letter published by Country Life on 7 December 1918, observed how ‘the capability of our land to produce more food-stuffs than in pre-war days has proved one of the most striking lessons which the war has taught us.’ Clynes backed up this claim by pointing to the production of ‘800,000 tons of vegetable produce’ from allotments across the country.

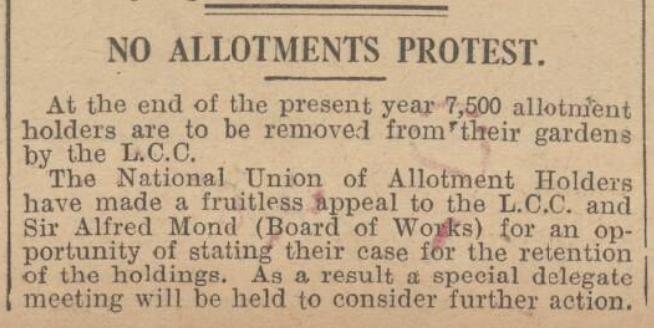

But with the war won, and over, there was now less of a need for allotments. On 14 August 1920 the Daily Mirror reported how ‘at the end of the present year 7,500 allotment holders are to be removed from their gardens by the L.C.C,’ London’s County Council. The National Union of Allotment Holders had made a ‘fruitless appeal’ to the council, in what the Daily Mirror dubbed to be an ‘allotments protest.’

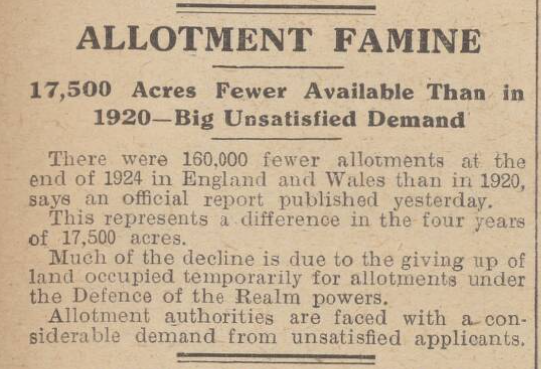

Four years later in September 1925 the same paper reported on the ‘allotment famine.’ The article detailed how:

There were 160,000 fewer allotments at the end of 1924 in England and Wales than in 1920, says an official report published yesterday. This represents a difference in the four years of 17,500 acres. Much of the decline is due to the giving up of land occupied temporarily for allotments under the Defence of the Realm powers.

However, allotments were still in demand, with the Daily Mirror relating how ‘allotment authorities are faced with a considerable demand from unsatisfied applicants.’

‘We Are Digging For Victory’

However, as the Second World War broke out, there was again a need for allotments. Allotment holders were this time reassured that they would ‘not lose their holdings should the war end suddenly.’ The Daily Mirror on 27 February 1940 reported how the Ministry of Agriculture had stipulated that ‘cultivators shall remain in possession until the official end of the war – which may be after the actual cessation of hostilities – and possibly for some time after that.’

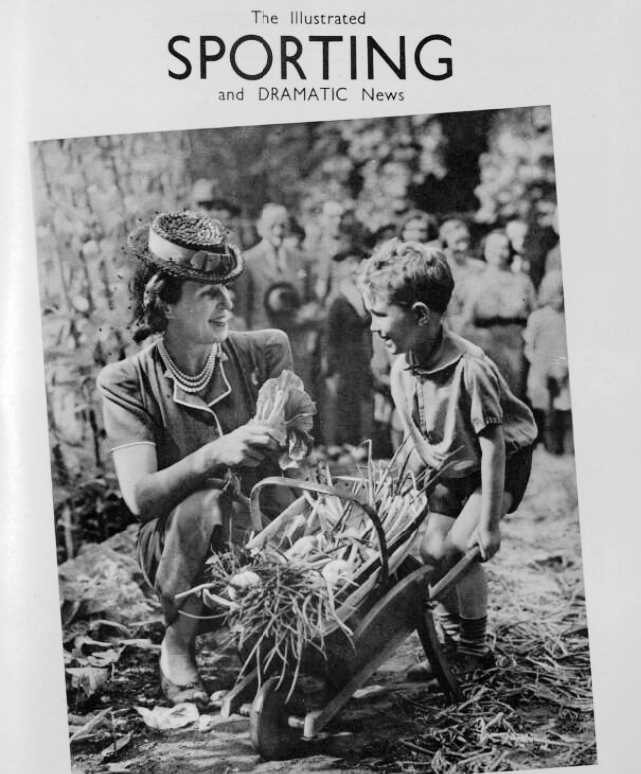

Allotments were once again in ascendance, and an integral part of the ‘Dig for Victory’ campaign. Allotments were again a key part of the war effort, and were imbued not only with patriotism, but with glamour. The pages of our Archive fizz with articles devoted to allotments, showing glamorous figures like the Philadelphia-born Minister of Agriculture’s wife Mrs. R.S. Hudson inspecting ‘the first of the season’s crops from the Hyde Park Allotments,’ as pictured by the Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News on 25 July 1941.

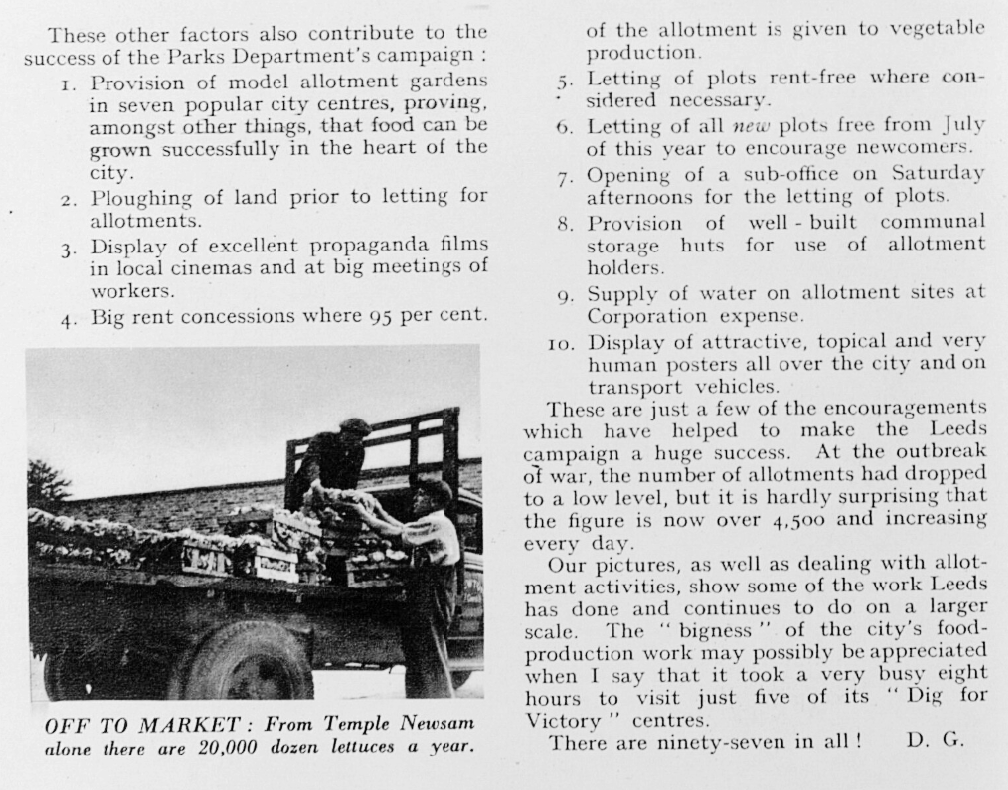

Meanwhile the same illustrated title took a trip to Leeds in September 1941, where ‘the entire city, from Lord Mayor and Aldermen down to the humblest of allotment holders, started planning to produce more food before the present war started and have been digging for victory since the day war was declared.’

The city, moreover, had hosted a special ‘Dig for Victory exhibition,’ which was attended by over 20,000 people. Contributing to the city’s success were ten key factors, which differ strongly from Mr. Robert Baker’s regulations of nearly a century before. For example, ‘big rent concessions’ were put in place ‘where 95 per cent of the allotment is given to vegetable production,’ whilst some plots were even let ‘rent-free.’ The city corporation, meanwhile, provided the allotment’s water supply at its own expense.

‘While I Can Still Dig’

Dig for victory fever was sweeping the land. In Plymouth Hoe, rescue workers of Plymouth’s Civil Defence organisation were photographed ‘digging up the Hoe for cultivation’ by The Sphere in May 1942. These allotments were then ‘let, free of charge, to the men, who are then allowed to take away the produce which they have grown on their allotments.’

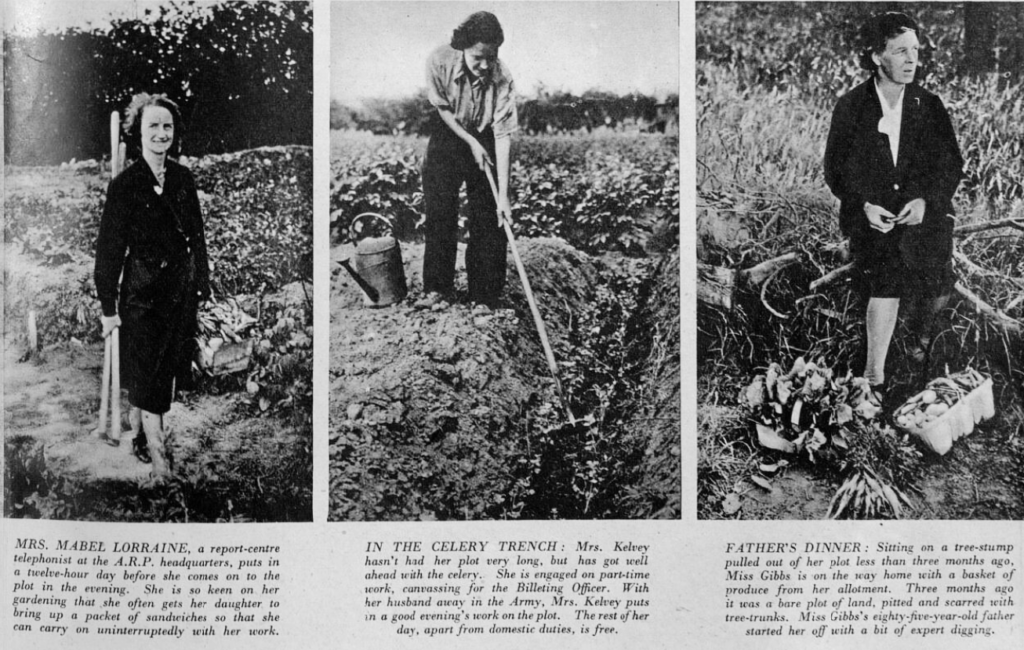

Meanwhile in August 1942 the Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News pictured the ‘Women of West Drayton,’ Middlesex, at work on their allotments. These allotments were situated in a ‘disused orchard’ at Rabb’s Farm, and numbered over 100 in total. The local council had arranged for the removal of six hundred trees and the ploughing of the land, where ‘peas, beans, carrots…potatoes and root crops’ were being grown by the women allotment holders.

These women were quite remarkable, as ‘almost all of them…[were] engaged in exacting wartime work in factories, in civil defence, or elsewhere on the Home Front.’ One such allotment holder was Grace Julian, who arrived at her plot ‘straight from her bench at a work factory.’ Grace would work six days a week, from 7.30 in the morning to 6.30 in the evening, making nuts and bolts. When the working day was over, she would ‘snatch a hasty meal in the canteen, and come straight on to the plot,’ still wearing her factory overalls.

Also working on the allotments at Rabb’s Farm was Mrs. Carter, ‘a bombed-out evacuee from Camberwell.’ The Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News describes how Mrs. Carter lost everything in a bombing raid, and now, ‘at the age of sixty-eight, although she had never touched a spade in her life before, she now runs two successful plots on this new site, as well as a garden back and front of her new home.’

Finally there was the redoubtable Mrs. Murphy, who is quoted by the Illustrated Sporting Dramatic News as saying ‘I’m not going to starve while I can still dig.’ She ran two allotments at the site, as well as a ‘fair-sized garden at home.’

Royals and Prizes

Aside from survival, allotments and the dig victory campaign provided opportunities for the winning of prizes, something we could perhaps compare to Mr. Robert Baker’s distribution of surplus profit in 1847?

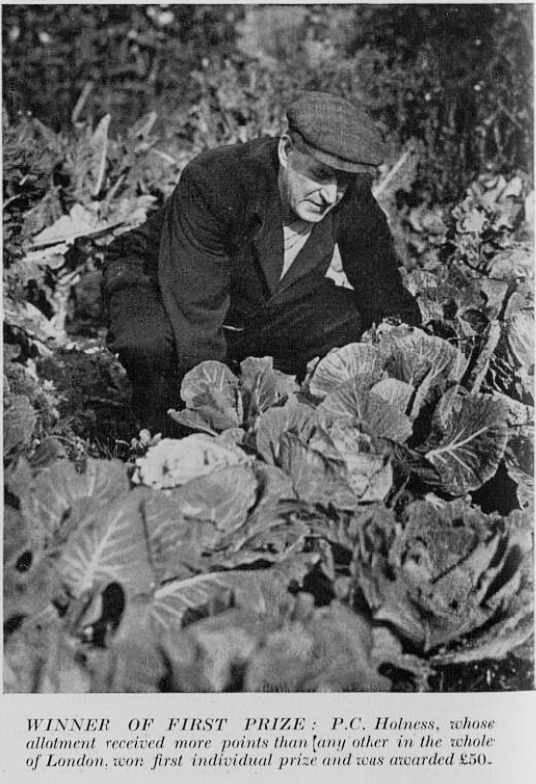

In November 1942 the Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News profiled the ‘Dig for Victory Winners’ in London’s Dig for Victory ‘allotment contest.’ A Lewisham policeman, Mr. E. Holness, was the winner of the individual first prize, whilst ‘seventeen of the 28 Metropolitan Boroughs entered, and in the Borough results, Battersea came first and St. Marylebone a close second.’

The competition provided an opportunity for the judges to praise ‘the immense contribution to our food supply that London allotments have provided.’ The panel, which included the head gardener of the Royal Gardens at Sandringham, Mr. C.H. Cook and the former curator of the Royal Botanical Gardens at Kew, Mr. T. Hay, described how:

Thousands of Londoners, for the first time, have enjoyed real green peas, crisp lettuces and fresh vegetables, hitherto unknown to them. They were particularly impressed by the fine crops of onions and also by the large quantities of winter greens being grown on many of the plots. They gave special praise to the plot holders in the congested districts of East and South London and expressed their amazement at the perseverance of cultivators of bombed sites.

The dig for victory campaign, therefore, summed up the spirit of the nation: redoubtable and unafraid to try new things. Meanwhile, the country’s figureheads, the royal family themselves, had their own allotments. The Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News on 20 November 1943 featured ‘the Royal allotments,’ which were to be found on the East Terrace of Windsor Castle.

Two of these allotments were under the care of Princess Elizabeth (later Queen Elizabeth II) and her sister Princess Margaret. The Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News noted how ‘it will please American and Canadian friends that the Princesses, behind their fine crop of dwarf beans, tried a few plants of sweet corn, which look like coming safely to maturity.’ The royal sisters were also growing potatoes, onions, carrots, runner beans, and lettuces.

‘Part of Our Heritage’

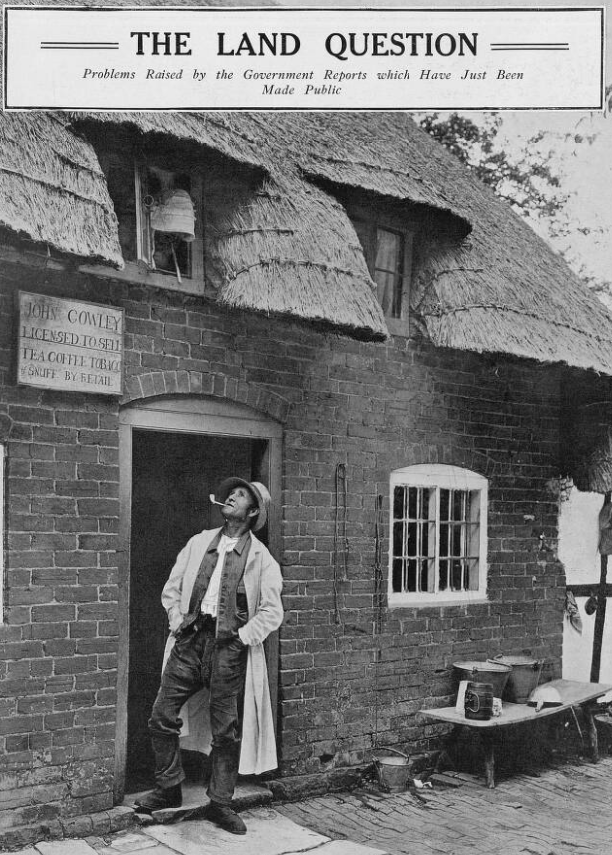

Fast forwarding several decades now to September 1998, when Mr. Ron Fry, Secretary of both the Harrogate and District Allotments and Gardens Federation and the Pine Street Allotments addressed the Knaresborough Horticultural Society. We wish indeed that we had been there, as his subject was ‘the history of allotments, from their early beginnings up to the present day.’

However, Ron Fry outlined how there had been ‘a nationwide decrease in the number of plots for rent, often due to the lack of tenancy protection and a tendency for Borough Councils to sell off sites for housing,’ as reported by local paper the Knaresborough Post. He went on to speak eloquently about the importance of allotments, stating how:

…because these sites have become part of our heritage and, in many instances, mini-nature reserves, providing green oases in the urban environment, and, whilst there are still so many who derive so much from cultivating allotments, it is to be hoped that their conservation and preservation will be seen as vital by more enlightened council members in the future.

Indeed, the 1990s became a time of renaissance for allotments. In increasingly busy cities, allotments allow for an escape into nature, as well as providing a way of living more sustainably. Allotments can be seen in many ways as symbols of liberation, as their development is tied to the notion of dividing land for all to use and to benefit from. Although over the years they have been utilised as tools of the state, expertly showcased through 1940s Dig for Victory propaganda, as Ron Fry said back in 1998, allotments allow people to benefit from ‘eating fresh, tasty produce,’ and also to experience ‘pleasure and friendship from this popular leisure pursuit.’

Find out more about allotments, gardening history, and much more besides, in the pages of our Archive today.