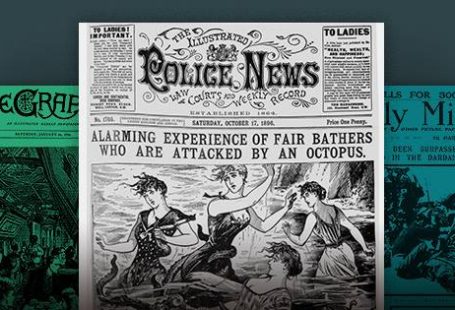

April Fool’s Day is the perfect day to delve into a topic that has of late appeared in the headlines: fake news. While its current iteration may seem particularly upsetting, it may be comforting (in a way) to learn that this is not a new phenomenon and it, in fact, plagued late nineteenth century journalism. In the United States, a new brand of ‘journalism’ emerged, coined ‘yellow journalism’—the clickbait of the pre-internet era. Joseph Pulitzer, now known mostly for the illustrious Pulitzer Prize, was actually responsible for the introduction of yellow journalism and was the father of the tabloid.

In 1884, after acquiring the New York World, Pulitzer grew readership by printing sensational stories, the veracity of which were often dubious. This approach saw the birth of tabloid journalism.

Yellow Journalism

The term ‘yellow journalism’ seems most likely derived from the ‘Yellow Kid’ cartoon. The cartoon first appeared in Joseph Pulitzer’s New York World. It would later appear in the New York Journal, owned by Pulitzer’s rival William Randolph Hearst. The rivalry between these two spurred on the growth of yellow journalism, which saw an escalation in the printing of sensational stories. In 1889, the editor of the Florida Daily Citizen, Lorettus Metcalf, asserted that due to the rivalry ‘the evil grew until publishers all over the country began to think that perhaps at heart the public might really prefer vulgarity’.

(Click to enlarge)

What fake news can you uncover?

Hoaxes

We would be remiss to talk about fake news without mentioning some of the most sensational hoaxes to captivate audiences near and far.

The Cottingley Fairies

The Cottingley Fairies refer to a series of five photographs taken by two young women, Elsie Wright and Frances Griffiths, in 1917. The photographs purported to be evidence of the existence of fairies. The photographs were, in fact, faked; in looking at the photos with twenty-first century eyes, used to the medium and its manipulation, the fabrication appears all too obvious. But in the early twentieth century, photo manipulation and the medium itself were still relatively new. One article commenting on the controversy of the veracity of the photographs wrote that ‘the camera, which, we are told, cannot lie’.

(Click to enlarge)

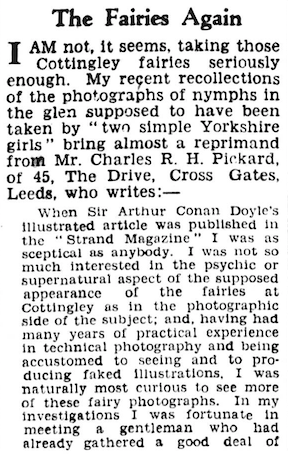

Even so-called photographic experts of the time were taken in by the photographs and convinced of their authenticity; take this argument printed in the Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer on 18 January 1944.

The photographs were made public in 1919 and caught the attention of individuals across the county. Whilst some were adamant about the photographs being fake, there were others equally convinced of their veracity. One such individual was Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, the man behind Sherlock Holmes. Doyle, a self-professed spiritualist, took the photographs as evidence of psychic phenomenon and wrote a book on the incident called The Coming of the Fairies. A review of the book in the Shipley Times and Express notes that ‘the so-called evidence and the inferences in this book will persuade only those who wish to be persuaded’. The review continues by noting that ‘Sir Oliver Lodge, who in this at least is typical of many more, was deeply interested in the photographs, but he could not be convinced that there was no trickery behind them’.

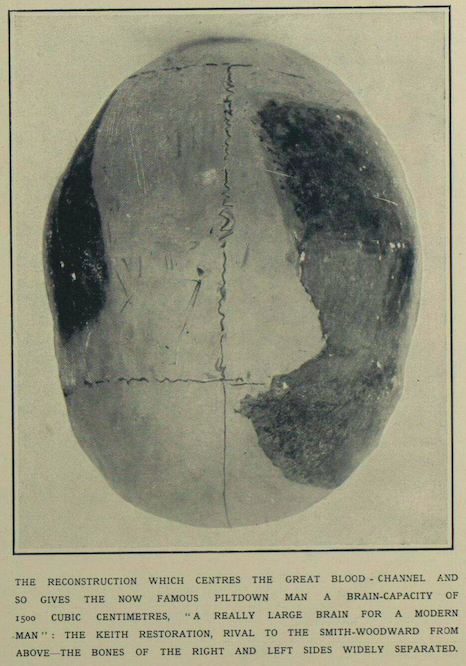

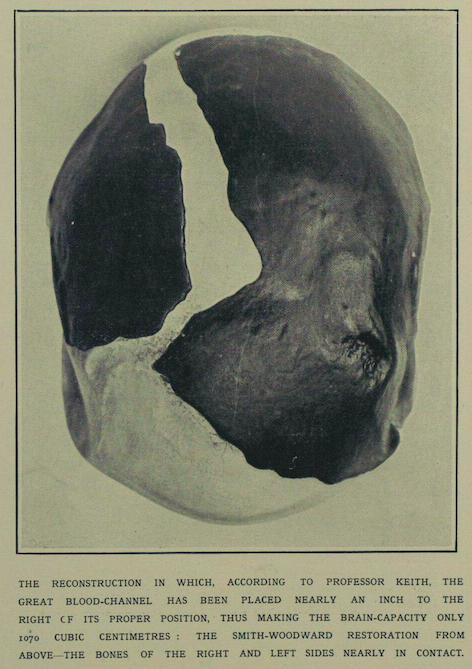

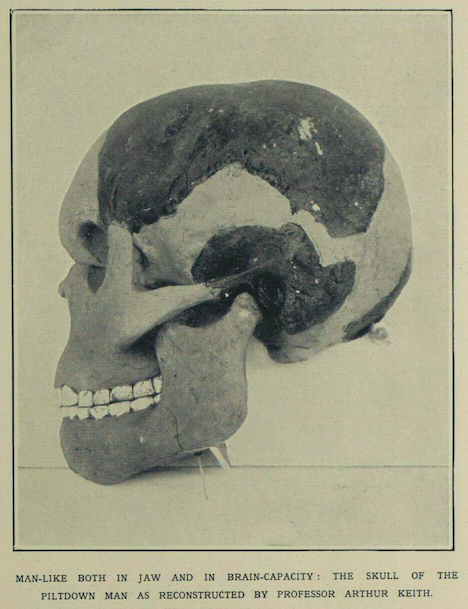

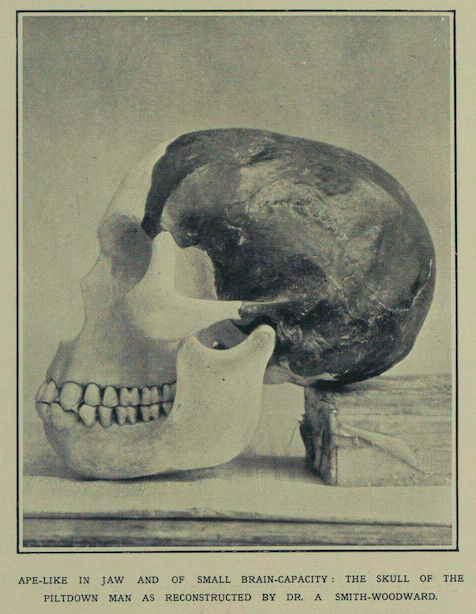

Piltdown Man

The Piltdown Man was a decades-long hoax. The hoax centered on Charles Dawson’s ‘discovery’ of what he claimed was the fossilised remains of an early human. The find was considered the ‘missing link’ between man and ape. The claim was not left unchallenged, but a definitive ruling proved difficult: the fragments presented by Dawson were studied and subsequently arranged by various researchers and based on their arrangements, either agreed or disagreed with Dawson’s claims. In an article from 23 August 1913, the Illustrated London News printed images of these differing arrangments.

Mary Toft

Mary Toft was at the heart of a medical hoax in 1726 – and a rather scandalous one at that.

Following her miscarriage, Mary claimed to have given birth to animal parts, specifically those of rabbits. In light of her shocking assertion, a local surgeon was called in. John Howard examined Mary and, it is reported, delivered some animal parts. Howard quickly spread the news to others in the medical field, prompting further investigations. Nathaniel St. André, the surgeon to the Royal Household, also corroborated Mary’s claim.

However, King George I called for Cyriacus Ahlers, another surgeon, to investigate. Ahlers was sceptical of Mary’s claims, and following her removal to London where she was examined exhaustively, Mary admitted to the hoax. Following her confession, Mary was arrested for fraud.

She would ultimately be released without charge, but the careers of those medical professionals who corroborated her story were ruined.