This day marks the 200th anniversary of Jane Austen’s death. During the last two centuries, Jane Austen has become a household name. Austen and her modest-sized collection of works has enjoyed a vibrant presence in both academia and western culture, from quotes on magnets and clothing to movie adaptations and sequels to her novels. Austen’s name is equally as at home in highbrow literary essays and criticism as it is in contemporary periodicals meant for mass consumption, such as the recent New York Times article on why exactly Austen’s work has endured.

This question of her endurance is not a new one, and the reasons for her novels staying power have similarly been discussed at length. The Aberdeen Press and Journal, on 18 October 1926, published the following:

Partially because these are days of flurry and rush many prefer for their leisure reading hours literature that is dignified, placid, and unhurried. For this reason Jane Austen will always share a wide circle of readers, but there is a perennial charm too in her exquisite cameo style and the delicate, satiric twist of her character portraits. Evidence of the continual popularity of her books is shown in the fact that, while Mr R. W. Chapman brought out a new edition in five volumes in 1923, the Oxford University Press now think it opportune to send out a reissue.

Aberdeen Press and Journal | 18 October 1926

The Scotsman published word of this reissue on 15 November 1926, noting that it ‘will be welcomed by all “Janeites”’ and that it is ‘an appropriately plain and dignified edition’.

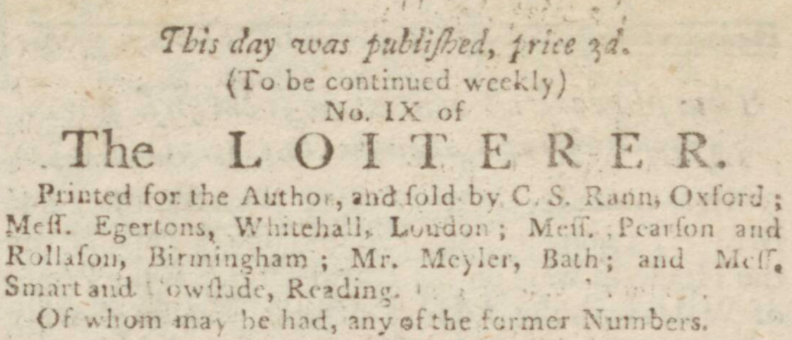

Jane Austen grew up in an intellectually-minded family who encouraged open discourse and creative pursuits. Far from the only writer in her family, her elder brother James penned a periodical in 1879 entitled The Loiterer. It has been hypothosised that a young Jane contributed to this publication in the form of a mock letter writer, ‘Sophia Sentiment’, who submitted a satirical letter to the editor. The tone and humour of the writing are in line with Austen’s early writings, and the issue of The Loiterer that included this letter is the only one to be advertised in the local paper, of which the Austens read, the Reading Mercury. Scholars have pointed to this as evidence of Jane as author of the letter, suggesting that James advertised this one issue as a surprise for Jane so that she could see her work in print.

In contrast to her supposed ‘Sophia Sentiment’ persona, Austen’s work was far removed from the usual sentimental writing of her age. From an article marking the centenary of her death, the Graphic noted the following of Austen’s work and legacy:

In direct contrast to those forgotten stories of exaggerated sentiment or pseudo-romance which were so popular in Jane Austen’s days, her novels hold the mirror faithfully to the rural English life of the time. Therein is their lasting charm. By their transmuted experience, their truth and simplicity, their endowment of the commonplace with variety and imagination, they will enable future generations to participate in the reflective pleasures of a different age. Perhaps it is not altogether loss for us to be reminded of the more restrained manners of other days.

Jane Austen’s novels

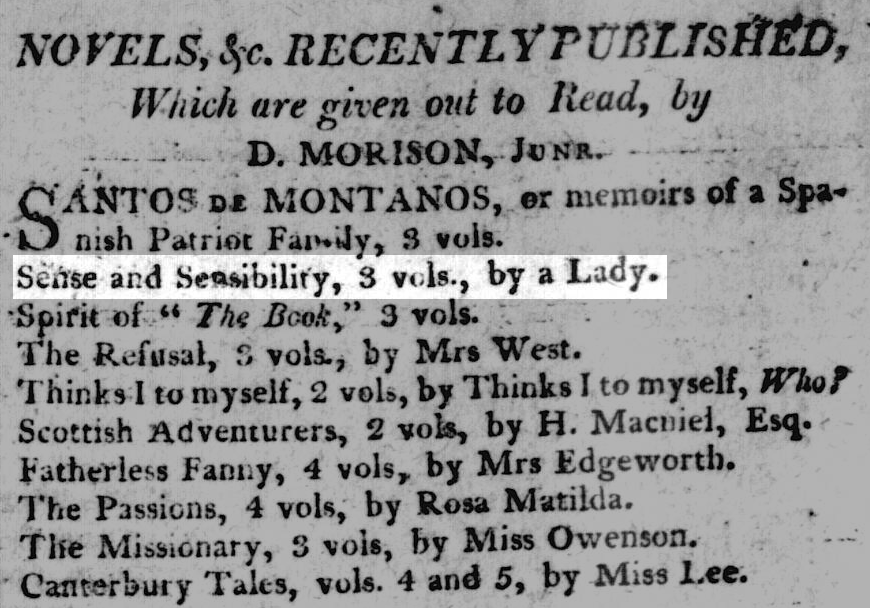

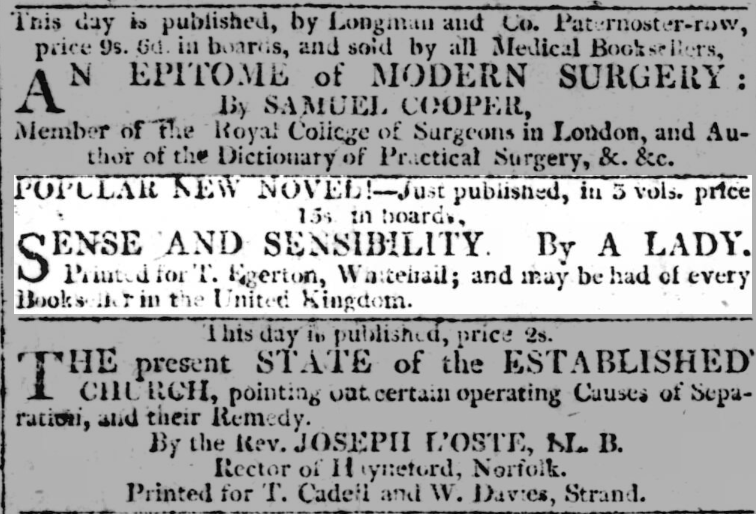

In her too-short career as an author, Jane Austen gifted us with seven complete novels: Sense and Sensibility, Pride and Prejudice, Mansfield Park, Emma, Northanger Abbey, Persuasion, and Lady Susan. While the surge in her popularity didn’t take place until the 1830s, some years after her death, her books were noted in the newspapers, particularly around their publication dates.

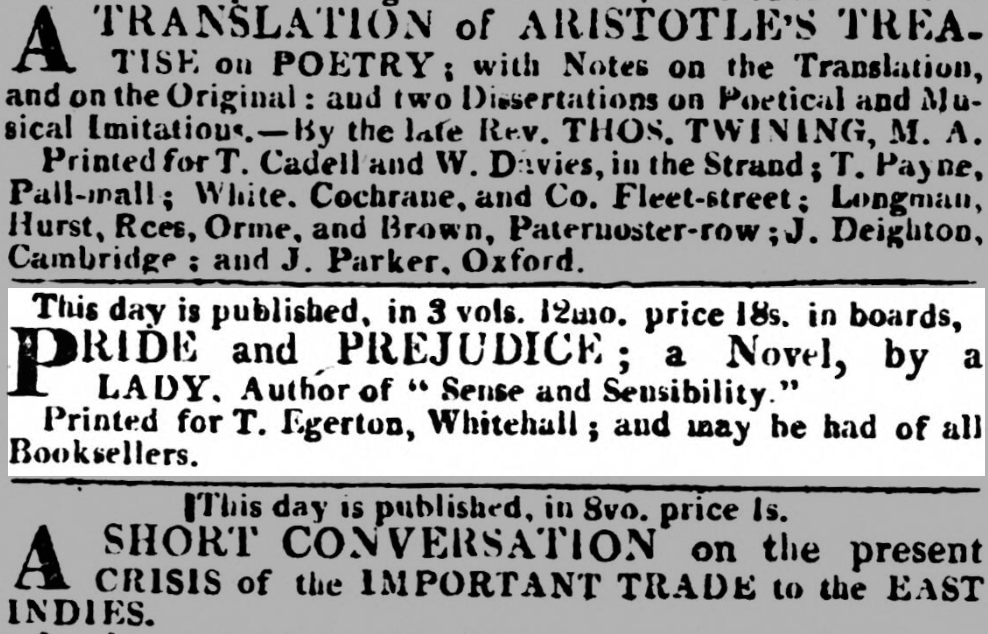

You can see from these notices that Austen’s works were published anonymously, with only her gender noted — ‘by a Lady’.

Austen sold the copyright for Pride and Prejudice to Thomas Egerton, and the first edition was printed in January 1813.

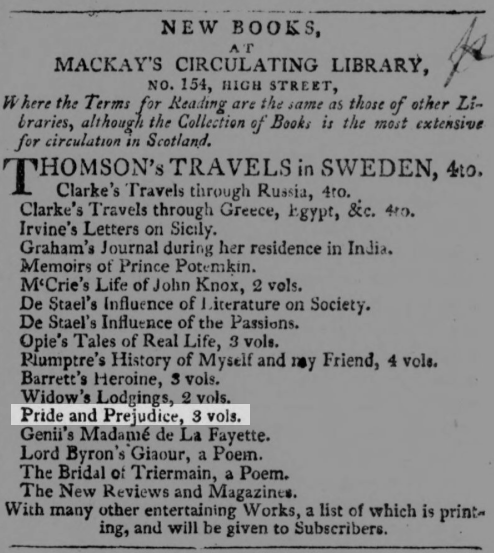

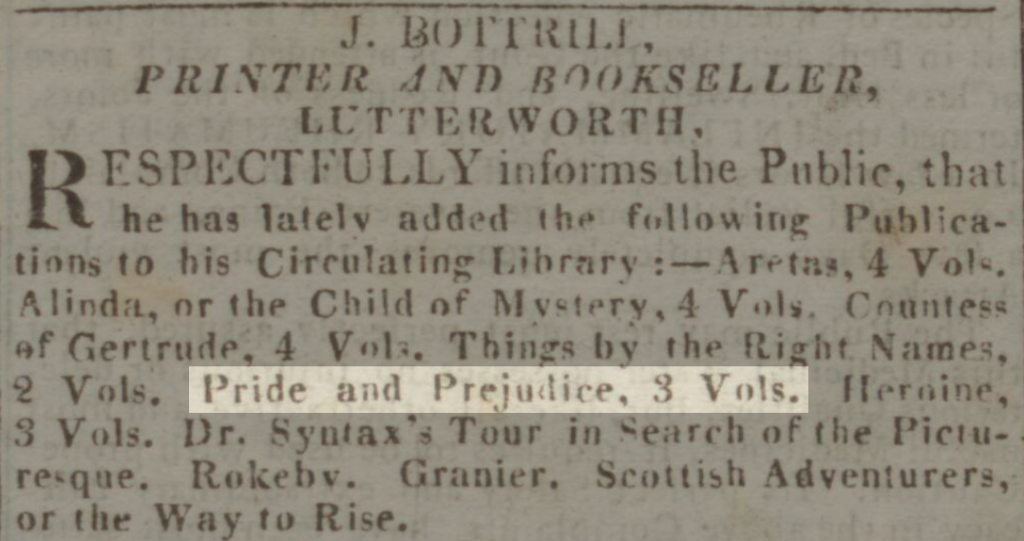

Further notices of Pride and Prejudice being added to various circulating libraries were likewise printed.

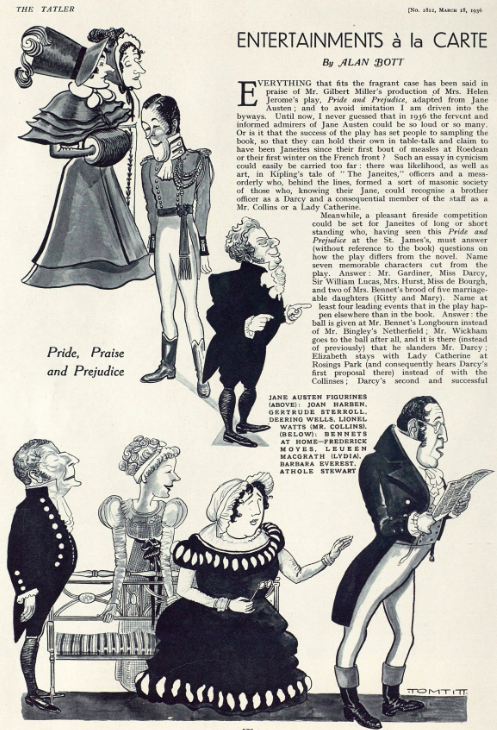

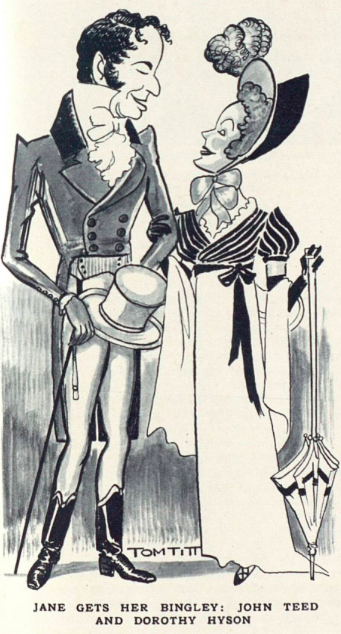

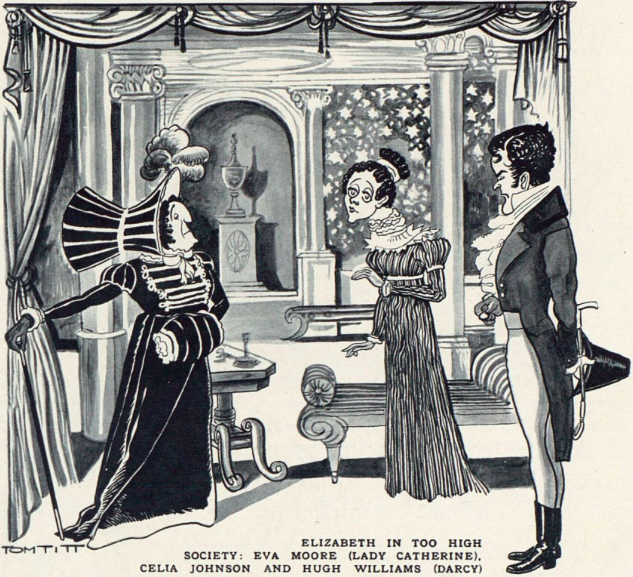

Pride and Prejudice has been adapted numerous times into films, been the subject of sequels and fanfiction, and has even made it to the stage. The following caricatures were done up in 1936 of the actors performing in Mrs Helen Jerome’s play Pride and Prejudice, adapted from the novel.

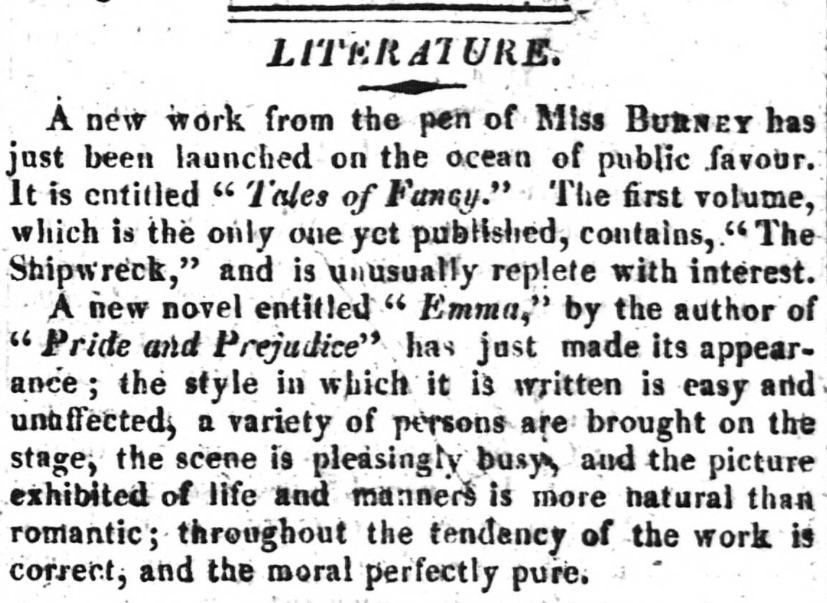

By 1815, with three novels under her belt, Austen’s Emma was published. The Morning Post printed a brief, complimentary review:

A new novel entitled “Emma,” by the author of “Pride and Prejudice” has just made its appearance; the style in which it is written is easy and unaffected, a variety of persons are brought on the stage, the scene is pleasingly busy, and the picture exhibited of life and manners is more natural than romantic; throughout the tendency of the work is correct, and the moral perfectly pure.

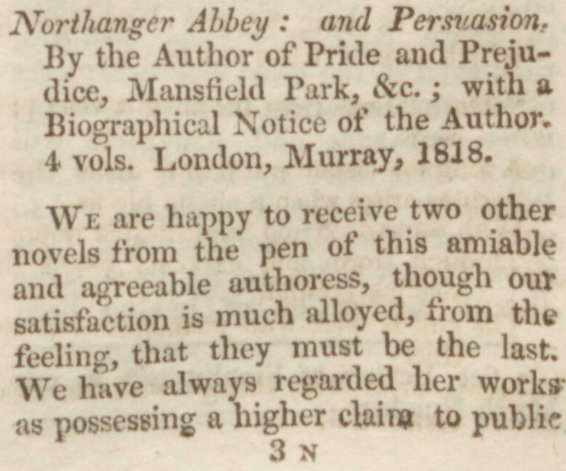

Three of Austen’s novels were published posthumously; two of the three were released almost a year after her death: Northanger Abbey and Persuasion. Upon receipt of these two novels, The Scots Magazine printed the following on 1 May 1818:

We are happy to receive two other novels from the pen of this amiable and agreeable authoress, though our satisfaction is much alloyed, from the feeling, that they must be the last. We have always regarded her works as possessing a higher claim to public estimation than perhaps they have yet attained.

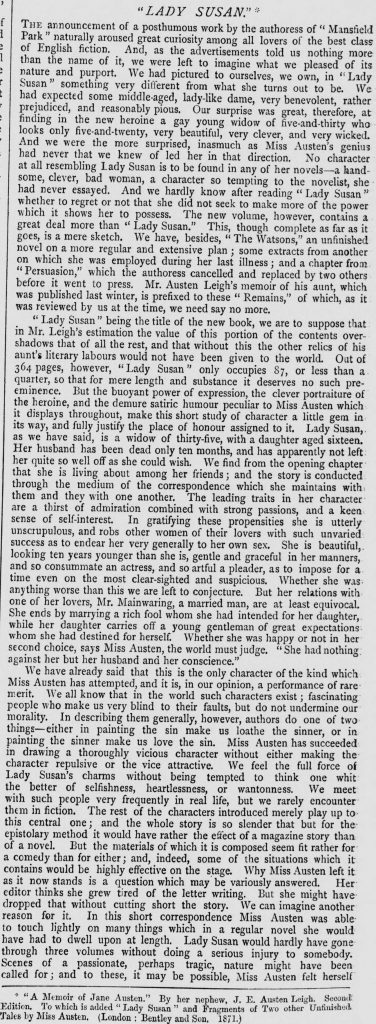

The third posthumous work was the epistolary novel, Lady Susan. It was written around 1794 but not published until 1871. On 6 July 1871, the Pall Mall Gazette printed its favourable review of the novel and its ‘very beautiful’ and ‘very wicked’ heroine, a novelty among Austen’s work.

No character at all resembling Lady Susan is to be found in any of her novels – a handsome, clever, bad woman, a character so tempting to the novelist, she had never essayed. And we hardly know after reading “Lady Susan” whether to regret or not that she did not seek to make more of the power which it shows her to possess.

While historically not as popular as Austen’s other novels, it may be enjoying a comeback: the 2016 film Love & Friendship was based upon Lady Susan (the film’s name was burrowed from Austen’s short story by the same title).

Celebrating and preserving the past

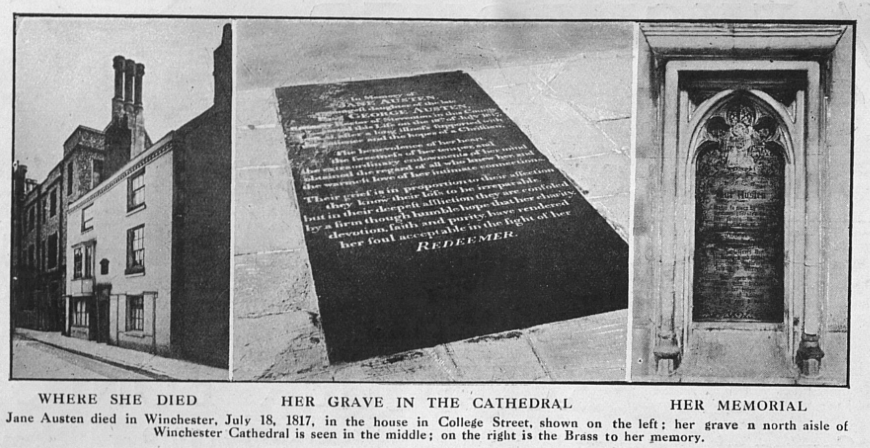

Jane Austen was buried in Winchester Cathedral in Hampshire. Images of her tomb and commemorative plaque were printed in the Graphic on 21 July 1917 as part of a piece commemorating the centenary of Austen’s death.

From the article marking her centenary, the Graphic wrote the following:

Jane Austen’s death caused no stir in the great world. Although her novels had won the unstinted admiration of Sir Walter Scott and other critical judges, her authorship of those novels was known to but few. Consequently her burial in Winchester Cathedral was a family, not a public, ceremony. She was laid to rest in the north aisle of that historic building, and a slab of black marble marks her resting-place. So many pilgrims have in more recent years sought out that simple grave that a verger of the cathedral once asked if there was “anything particular about that lady.” Subsequently a simple memorial brass was fixed to the wall near the grave; but on neither the marble nor the brass is there that eulogy of her genius which literary appreciation would be prone to pen today.

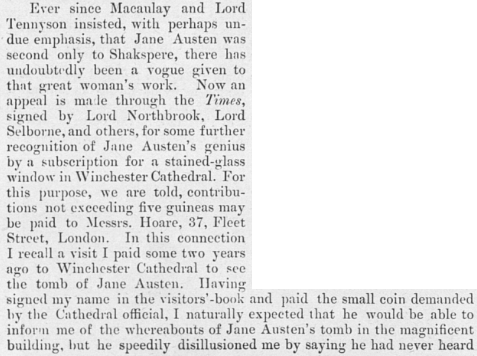

In 1898, there was an appeal made for funds to install a stained-glass window by Austen’s resting place, as a mark of further recognition for Austen and her literary contributions.

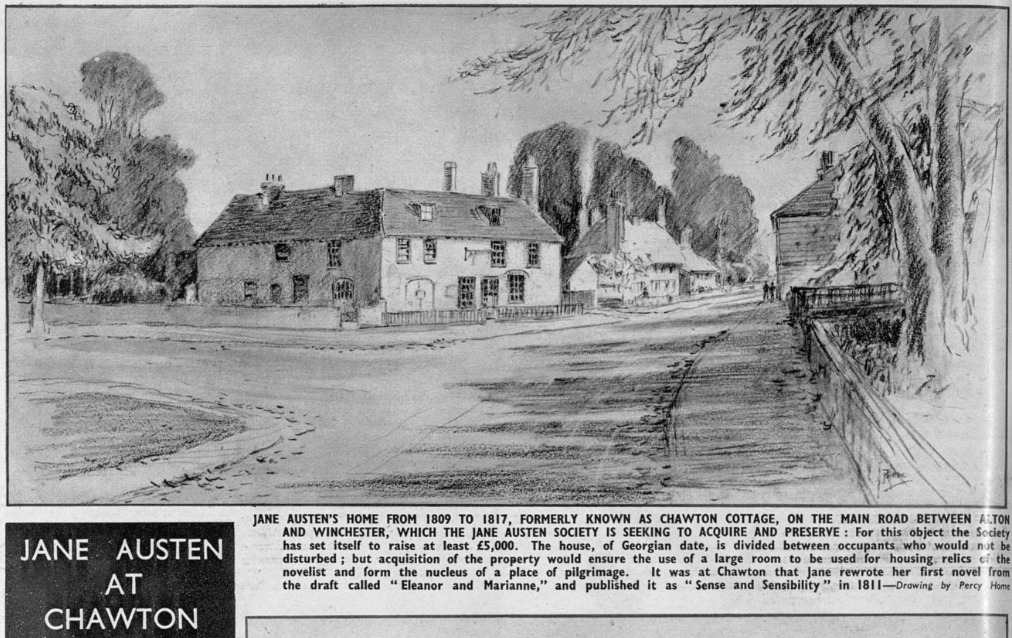

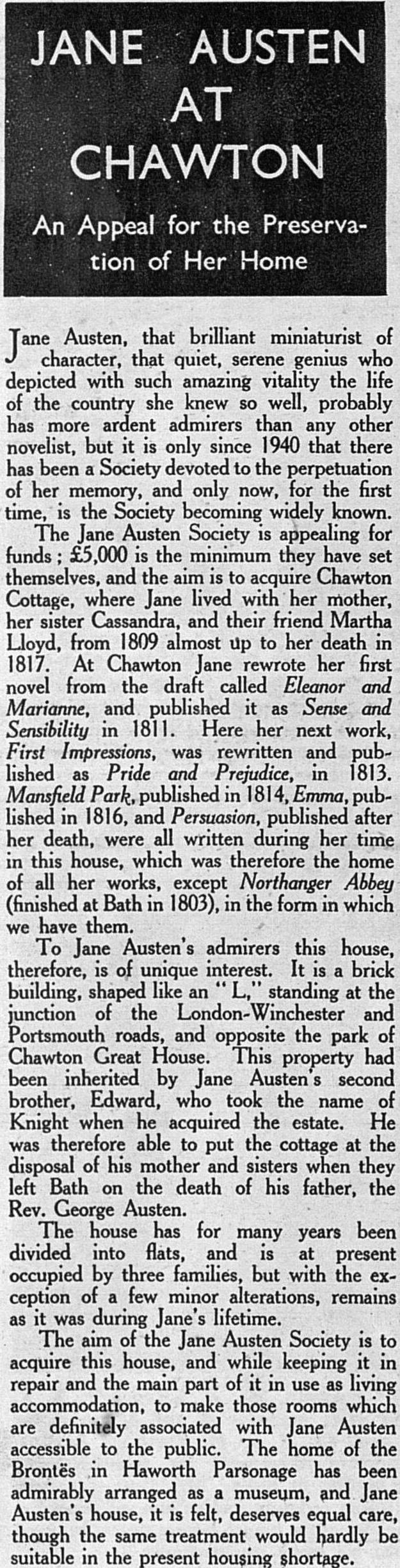

Owing to the efforts of early preservationists, we can today enjoy the Jane Austen’s House Museum. An appeal to preserve the Chawton house is found in The Sphere from 4 January 1947 and includes an illustration of the home.

While we today so admire Austen for her literary merits and genius, it is well that we remember the woman she was and the life she lived:

As Mr. Goldwin Smith pointed out, novel-writing was not the whole of Jane Austen’s life. “She had a domestic and social life independent of it, and full both of enjoyment and duty. People could see her constantly without guessing that she was an authoress.” Dowered with a fair share of good looks, brunette in complexion, and of tall and slender figure, Jane Austen had such accomplishments in playing and singing as made her a welcome addition to any social gathering. But what was her greatest charm was that sweetness of disposition to which all her relatives and friends bore unanimous testimony. Hence when death claimed her at too-early age it is not surprising her relatives estimated their greatest loss in the terms of her character than that in the deprivation of her genius. Their grief, they affirmed on her tomb, was “in proportion to their affection” instead of mere admiration.

Discover more Jane Austen-related history in The British Newspaper Archive by registering today!