Born in Nashik, in what was the Bombay Presidency in British India, in 1866, pioneering lawyer Cornelia Sorabji would go on to be the first woman graduate of Bombay (Mumbai) University, and the first woman to study law at the University of Oxford.

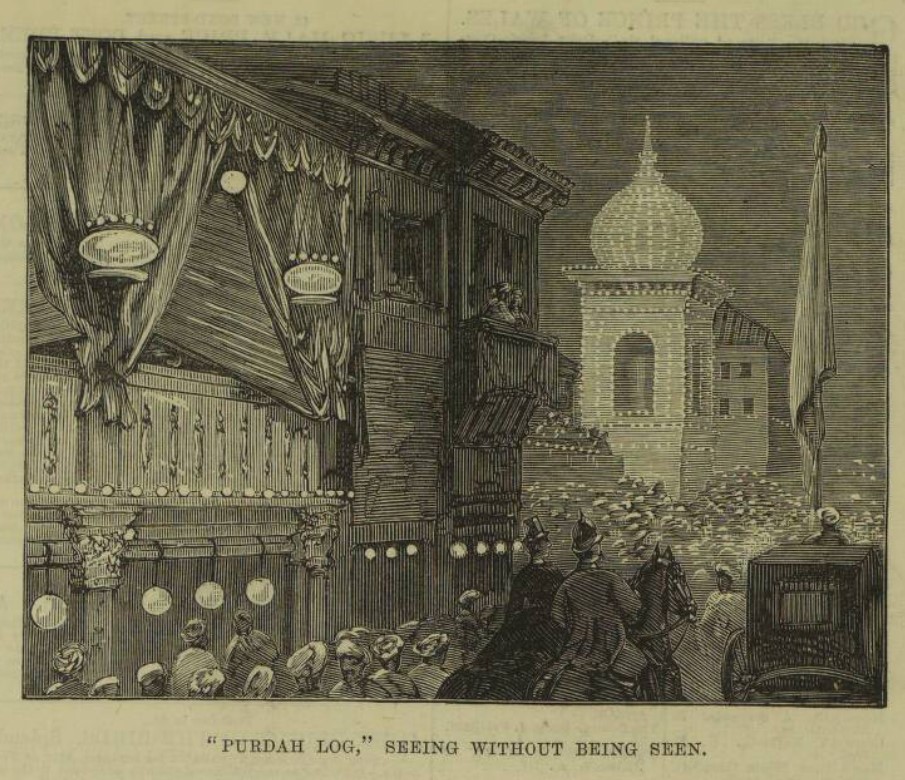

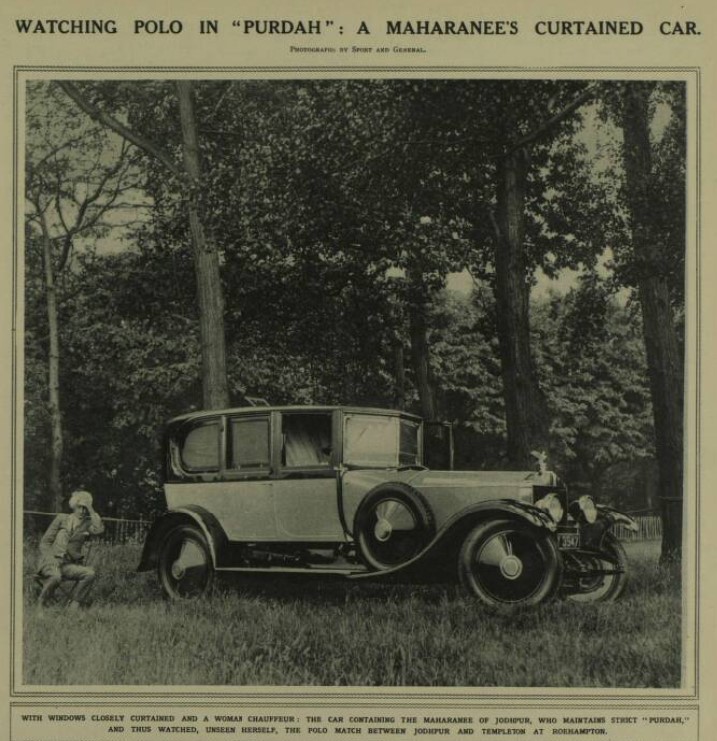

A pioneering figure, Cornelia Sorabji worked on the behalf of purdahnashins, women who could not communicate with the outside male world. Indeed, she entered upon a legal career to help these women. Cornelia Sorabji’s life, however, was not without controversy, as she supported the British Raj and was opposed to Indian home-rule.

In this special blog, we will look at how the life and career of Cornelia Sorabji was reported on through our newspapers, from both a British and an Indian perspective.

Register with us today and see what stories you can discover

‘The First Lady B.A. Of The Bombay University’

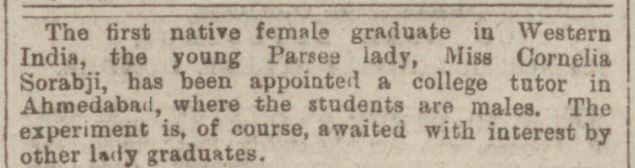

One of the earliest mentions we found of Cornelia Sorabji comes from Scottish newspaper the Dundee Courier in April 1888, which described how:

The first native female graduate in Western India, the young Parsee lady, Miss Cornelia Sorabji, has been appointed a college tutor in Ahmedabad, where the students are males. The experiment is, of course, awaited with interest by other lady graduates.

As a Parsee (or Parsis), Cornelia Sorabji was part of an ethnoreligious group in India, who were followers of Zoroastrianism and had emigrated from Persia. However, her father Sorabji Karsedji had converted to Christianity and become a missionary. Meanwhile, Cornelia Sorabji’s mother, Francina Ford, was a keen supporter of girls’ education in their home place of Poona (now Pune).

And just as her mother was a trailblazer for women’s rights, Cornelia Sorabji would be too, and one of the first steps in that journey was when she became the first woman to graduate from Bombay University in 1888.

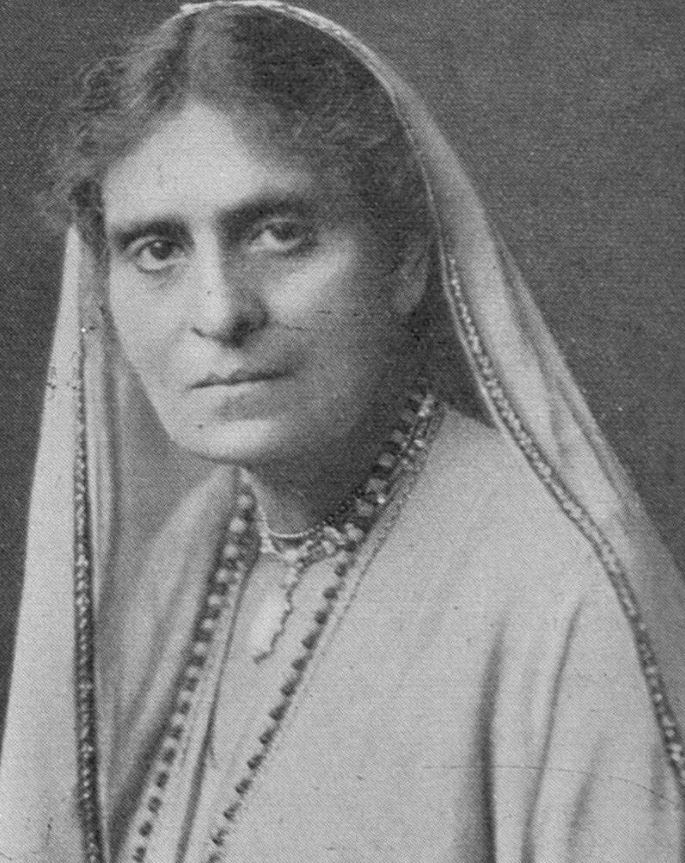

On 21 June 1888, Lahore-based newspaper the Civil & Military Gazette profiled ‘the first lady B.A. of the Bombay University,’ whilst British-based weekly The Graphic featured her likeness. The Civil & Military Gazette article began by stating:

Women all over the world are bestirring themselves to the assert their sometimes questionable, but in many cases perfectly justifiable, claims to a status in culture, art, politics &c., equal to that of men. Their fitness and right of doing so cannot be doubted any longer, considering the successes they have achieved at the universities of Great Britain, India, the United States, and on the Continent.

The piece goes on to describe Cornelia Sorabji ‘as a case in point.’ It narrates her achievements in being ‘the first and only lady to enter the Deccan College at Poona in 1884,’ where she was the only woman student amongst 300 men. Although, as the Civil & Military Gazette notes, it was ‘a difficult position,’ Cornelia Sorabji was able to win ‘golden opinions from principals and professors alike.’

The article goes on to chronicle her further achievements:

She studied Latin in common with the men (though French has since been allowed to lady-students). She was ‘top of her year’ in the previous examination, has held a scholarship each year of her course, was ‘Hughling’s Scholar’ in 1885, having passed head of the University of English, ‘Havelock prizeman’ the end of the same year, being top of the Deccan College in English, has taken honours each time, and in the final B.A. examination of the Bombay University, held in November 1887, she was one of the four in the entire college who succeeded in gaining first-class honours.

A true pioneer, the Civil & Military Gazette describes how three women were already following in Cornelia Sorabji’s footsteps by attending colleges in Bombay and Poona.

‘A Lady Lawyer’

Having broken the mould by receiving a first-class degree in literature from Bombay University, Cornelia Sorabji turned her attention to the study of law, in order to assist purdahnashins. These women, many of whom were extensive property holders, could not communicate with the outside male world, and had no means of representation in court, something Cornelia Sorabji sought to remedy.

To this end, she went to Oxford University to study law, as the Illustrated London News later recalled in December 1934. She qualified for the B.C.L. (Bachelor of Civil Law) in 1892, but ‘as women were not admitted to degrees till after the [First World] war, she did not actually obtain hers till thirty years later.’

In August 1896 the Homeward Mail from India, China and the East described Cornelia Sorabji’s appearance in the Poona Sessions Court:

Miss Sorabji put her case in a logical, though perhaps not very forcible, way. This being, we understand, her first appearance in a Poona law court, the probability was that the lady was a little nervous (the court was crowded with men) – and for this reason, perhaps, the forensic force of her address was not so pronounced as was the logic of her deductions, but throughout her appeal to the jury she was never at a loss for a word; and, moreover, when pulled up by both opposing counsel and judge, betrayed no flurry, but argued the point with a calmness and consistency that would have done credit to a veteran pleader of the sterner sex.

Whilst labelling her ‘quiet and conversational rather than professional and powerful,’ the Homeward Mail reported how ‘no point in her clients’ favour was missed.’ Indeed, the newspaper admitted how there was scope in India ‘for lady practitioners’ due to the ‘difficulties of purdah obligations,’ and as such, ‘Miss Cornelia Sorabji and other lady-pleaders practising in India will have the sympathy of a large class of inhabitants and their best wishes for a successful and useful career in their profession.’

The report finished with the news that Cornelia Sorabji, a ‘pioneer of her sex,’ had the ‘satisfaction of seeing her clients, who were charged with manslaughter, acquitted.’

Honours and Distinctions

In the following years, newspapers both in Britain and India, and beyond, reported on the legal career of Cornelia Sorabji.

In July 1904 the Islington Gazette reported how Cornelia Sorabji had ‘received the appointment of Legal Advisor to the Court of Wards under the Government of Bengal.’ The article described how:

She has persistently urged the importance of providing female legal assistance for Indian women who are secluded behind the Purdah. Her conviction of this need was upheld by the opinion of several officials in India, and after consideration had been given to his subject, the Government of Bengal have decided to make a trial in this direction. Miss Sorabji had already privately given legal advice to some of these ladies, but she has now the satisfaction of working officially.

A few years later, in June 1907, Lahore’s Civil & Military Gazette was reporting how the ‘Lieutenant-Governor of Bengal [had] appointed Miss Cornelia Sorabji a member of the Bethune College Committee.’ Bethune College, established in 1879, was the first women’s college in Asia, and it is based in Kolkata to this day.

Meanwhile, in 1909 The Sphere described how ‘during the past week many honours and distinctions have been bestowed on women.’ One of the women to be so honoured was Cornelia Sorabji, ‘the well-known Indian barrister,’ who was awarded the Kaiser-i-Hind gold medal by King Edward VII. The Kaiser-i-Hind medal was awarded by the Emperor or Empress of India during the British Raj to those who distinguished themselves ‘by important and useful service in the advancement of the public interest’ in British India.

Cornelia Sorabji’s service continued to be highlighted by the press of the day. Her work was highlighted by Truth in December 1911, which described how she travelled ‘the length and breadth of the land taking legal advice behind the purdah,’ describing her as ‘almost the first Indian woman to think of qualifying in law in order to help her secluded sisters.’

Some ten years later in 1921, and Suffolk newspaper the Framlingham Weekly News was keeping track of Cornelia Sorabji’s career. The publication reported how Cornelia Sorabji, as ‘the first woman enrolled as a barrister at the High Court of India,’ had ‘begun practice in Allahabad.’

‘Women’s Bar Successes’

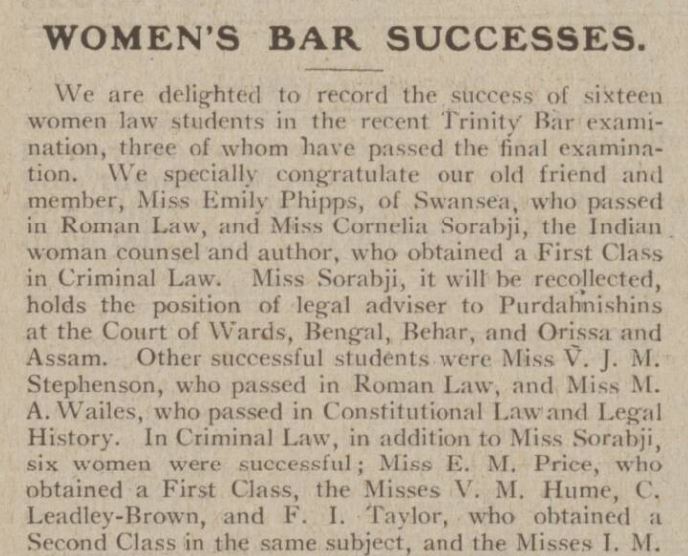

And by 1922, just over one hundred years ago, both Cornelia Sorabji and other women in Britain were making waves in the legal sphere. Women’s suffragist publication the Vote joyfully reported on ‘Women’s Bar Successes‘ in June 1922, writing how:

We are delighted to record the success of sixteen women law students in the recent Trinity Bar examination, three of whom have passed their final examination. We specially commend our old friend and member, Miss Emily Phipps, of Swansea, who passed in Roman Law, and Miss Cornelia Sorabji, the Indian woman counsel and author, who obtained a First Class in Criminal Law.

The Vote took the time to remind its readers how Cornelia Sorabji held ‘the position of legal adviser to Purdahnishins at the Court of Wards, Bengal, Behar, and Orissa and Assam.’

It was in 1923 that Cornelia Sorabji would finally be recognised as a barrister, thanks to a change in the law that allowed women to now hold the position. From 1924 Cornelia Sorabji began practising in Calcutta (Kolkata), and in 1929 the Vote described some of her work there, where she had set up ‘a scheme for training social workers.’

Books and Talks

In 1929 Cornelia Sorabji settled in London, returning to India every winter. She continued to appear in the newspapers, as she published multiple books and gave talks around the country.

In December 1934 the Illustrated London News reviewed her book India Calling. Showcasing Sorabji’s memories of India and beyond, the publication also contained ten illustrations. India Calling was mainly concerned ‘with Indian womanhood and the purdah system,’ but it also contained some recollections about the author’s time in England, ‘and especially of Oxford, where Jowett confided to her that he once proposed to Florence Nightingale.’

A few years later, in 1937, Cornelia Sorabji was taking to the airwaves of Britain. As previewed by the Dundee Evening Telegraph in November 1937, she was due to conduct a ‘teatime talk’ on ‘Women in Changing India.’

In April 1939 she visited the Sussex seaside town of Worthing, as reported the Worthing Gazette, to address the Worthing Branch of the National Council of Women, and the Women Citizen’s Association. ‘Wearing a beautiful sari,’ Cornelia Sorabji spoke on the subject of ‘The New India.’

A Chapter Comes To Its Close

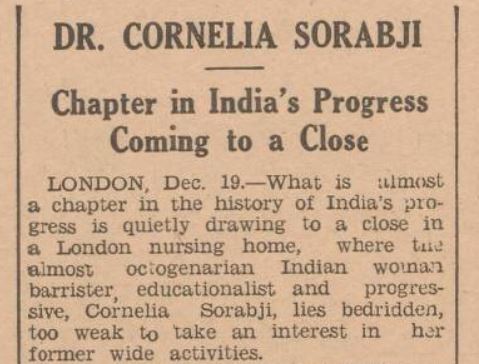

However, in December 1945 the Civil & Military Gazette was reporting how a ‘chapter in India’s progress [was] coming to a close,’ with the sickness of Cornelia Sorabji being made public. The article begins by describing how:

What is almost a chapter in the history of India’s progress is quietly drawing to a close in a London nursing home, where the almost octogenarian Indian woman barrister, educationalist and progressive, Cornelia Sorabji lies bedridden, too weak to take an interest in her former wide activities.

The pioneering lawyer had been carrying on ‘her various activities’ until a collapse some three months before. She had overcome a ‘street accident’ in 1941, in which she broke her leg, had two operations on her eyes, and had survived three near misses during the Blitz.

Her younger sister, Dr. Alice Maude Pennell, was quoted by the newspaper as saying:

‘My sister’s condition is getting worse and I fear her work is all behind her. She is suffering much pain with great bravery. One of her greatest disappointments is that she is unable to write another book. But one must be philosophical and be thankful there is no lack of younger Indian women to follow in her footsteps.’

However, ever the fighter, Cornelia Sorabji would live for another nine years, dying at the age of 87 in Green Lanes, North London, in 1954. During the course of her career, it is estimated that she helped over 600 women and orphans with legal advice and representation, sometimes without charge.

Find out more about Cornelia Sorabji and other inspiring women in our Archive today.