October is Black History Month, and to celebrate, here at The Archive we are uncovering the amazing stories of Black British figures from history. In this first of a series of special blogs, we begin by celebrating the work of five Black British musicians, and highlighting their amazing legacies, using newspapers taken from The Archive.

Register now and explore The Archive

So read on to discover more about child prodigy George Bridgetower who took the courts of Europe by storm in the late eighteenth century, violinist Joseph Antonio Emidy who entertained Regency society, and radio and stage star of the twentieth century Evelyn Dove – as well as the immensely talented turn-of-the-century composer Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, and the incomparable Bond songstress Shirley Bassey.

George Bridgetower

In January 1789 George Frederick Augustus Bridgetower, aged only ten years old, made his ‘entrée in the world as a musician.’ Saunders News-Letter reports how this young boy ‘promises to be one of the first players in Europe,’ his instrument the violin, and his teacher Austrian composer Joseph Haydn.

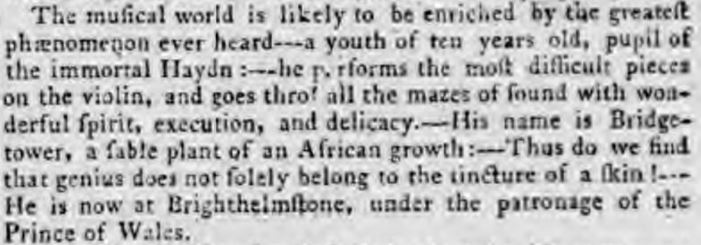

The Chester Chronicle, later that year in August 1789, writes further of young Bridgetower’s talents, labelling him the ‘greatest phenomenon ever heard.’ It describes how he ‘performs the most difficult pieces on the violin and goes thro’ all the mazes of sound with wonderful spirit, execution, and delicacy.’

Chester Chronicle | 14 August 1789

As George Bridgetower was of African descent, the newspapers of the time were strongly preoccupied with his race, the Chester Chronicle noting how ‘genius does not solely belong to the tincture of a skin!’

Born in Poland, George Bridgetower’s mother was a Polish aristocrat, whilst his father was from the West Indies, and it was often reported that he was an African prince. The Kentish Gazette tells of how Bridgetower’s father John Frederick was ’emancipated’ by his enslaver in Jamaica, before travelling to Russia, Italy, Germany and France.

But it was Britain that his son was to make his home, making him one of Britain’s earliest Black musicians and composers. The Chester Chronicle reports in August 1789 that Bridgetower had been taken under the wing of the Prince of Wales, and from this point on our newspapers record the various concerts in which Bridgetower performed.

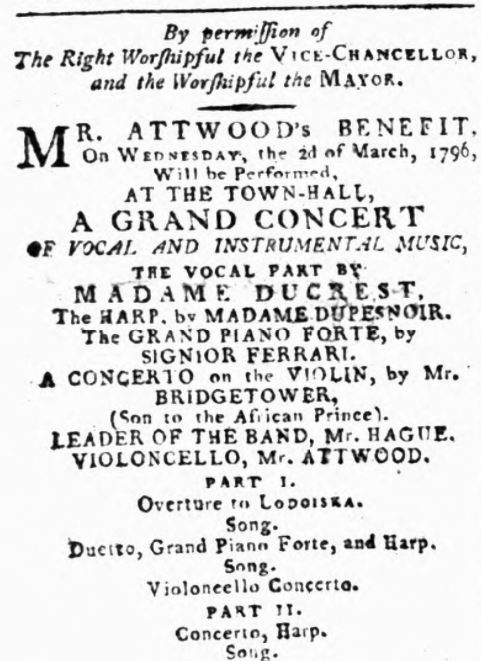

For example in 1796 Bridgetower performed at Mr Attwood’s Benefit, as described in the Cambridge Intelligencer. In parenthesis it is noted how he is ‘son to the African prince.’

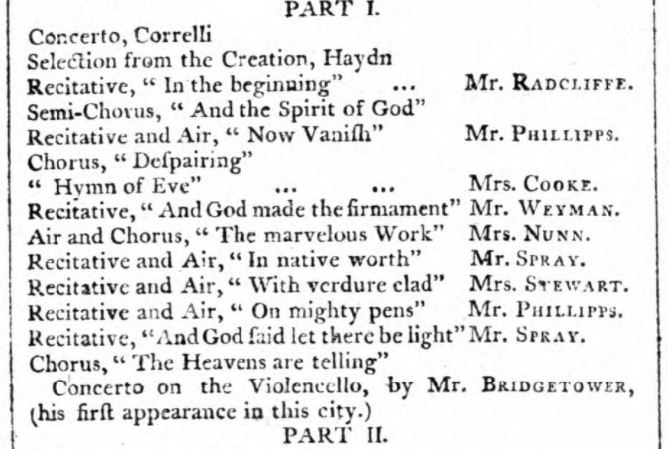

Meanwhile, his brother Frederick Bridgetower, a talented cello player, joined George from Europe in 1805. In 1808 Frederick played for the first time in Dublin, for the ‘Benefit of the Incorporated Irish Musical Fund Society, for the relief of distressed Musicians and their Families’ (Dublin Evening Post, April 1808). Frederick settled in Dublin, marrying an Irish woman there, but sadly died young in 1813.

Concerto on the Violencello by Mr Bridgetower | Dublin Evening Post | 7 April 1808

We will come back to the immensely talented George Bridgetower, his friendship with one of the greatest composers who ever lived, and how his legend lived on in British music and culture long after his death in 1860.

Joseph Antonio Emidy

Joseph Antonio Emidy was born in Guinea in 1775, and as child he was enslaved by Portuguese traders. After gaining his freedom, he was pressganged into the British Navy where he served as a ship’s fiddler, before he was eventually discharged in Cornwall.

Emidy was a talented violin player, like his contemporary George Bridgetower. And he too was set to impress those around him with his musical talent, entertaining members of Cornwall high society at concerts and balls throughout the early nineteenth century.

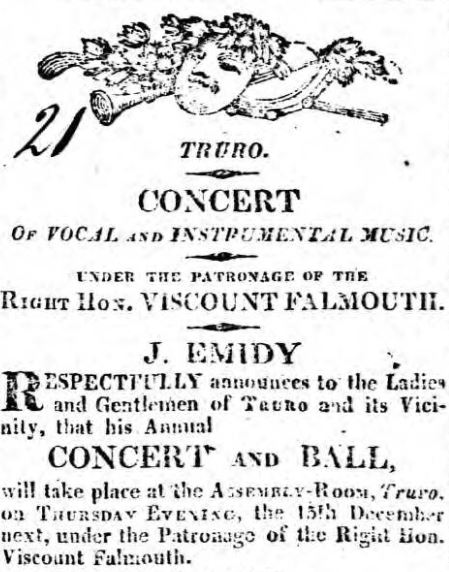

Royal Cornwall Gazette | 26 November 1814

In November 1814 an advertisement for a ‘Concert of Vocal and Instrumental Music‘ appeared in the Royal Cornwall Gazette, running as follows:

J. Emidy Respectfully announces to the Ladies and Gentlemen of Truro and its Vicinities, that his Annual Concert and Ball will take place at the Assembly Room, Truro, on Thursday Evening, the 15th December next, under the Patronage of the Right Hon. Viscount Falmouth.

Emidy also advertises ‘Lessons on the Violin, Tenor, Violoncello and Flute,’ as well as his pianoforte turning services. Emidy’s concert was a huge success, the Royal Cornwall Gazette reporting that it was ‘numerously and fashionably attended,’ hailing Emidy’s ‘taste in selection’ of pieces. It goes on further to compliment the pioneering Black musician:

Mr Emidy’s Concert on the Violin, has seldom been excelled, either in composition or execution:- the taste displayed by him the variations of the air introduced as the subject of the Rondo (the Bugle Waltz) and the clearness and precision he displayed in the performance of the most intricate passages, drew forth long and well merited bursts of applause.

Royal Cornwall Gazette | 17 December 1814

Emidy continued to draw praise as the years went on. He became the leader of the Truro Philharmonic Orchestra, composing his own work, and thus making him one of Britain’s earliest Black composers.

His ‘very efficient manner of leading the Band and admirable execution of his Violin solo’ drew further praise from the Royal Cornwall Gazette in November 1815, at another concert and ball which again was ‘very respectably and fully attended.’

Joseph Emidy’s race is not commented upon in the newspapers of the time. It is impossible to speculate as to why this might be, and of course does not mean that Emidy did not face any racial prejudice, but it seems to show that he was embraced by the local Cornish community whom he entertained with such talent and skill.

Royal Cornwall Gazette | 23 October 1835

Emidy died in 1835, and his wife Jane, daughter of a local tradesman, took the opportunity to thank the ‘Gentry and Public…for the continued favours bestowed on her late husband during the period of nearly 35 years.’ A further concert and ball was organised for her benefit in Falmouth, as the Royal Cornwall Gazette reports.

Meanwhile, Emidy’s son William was set to follow in his father’s footsteps, having ‘taken lessons on tuning the Piano Forte, and is fully competent to take his father’s place in that department.’ Thus, Joseph Emidy’s musical legacy lived on in the shape of his son.

George Bridgetower & a Beethoven Sonata

Meanwhile, George Bridgetower’s musical legacy was too live on also, as twenty years after his death in 1860 the newspapers still mention his name, as he rose to a kind of mythical status. In 1884 the Aberdeen Evening Express is (incorrectly) reporting him to be the ‘descendant of an Indian prince,’ but the same article also highlights Bridgetower’s friendship with none other than Ludwig van Beethoven.

Indeed, Bridgetower’s legacy would have been all the more heightened had not a quarrel taken place between him and Beethoven. In the early 1800s, Bridgetower and Beethoven were close friends, and whilst Beeethoven was composing a new sonata, they were ‘constant companions,’ as reports the Aberdeen Evening Express.

Ludwig van Beethoven | Illustrated London News | 23 January 1909

The Nottingham Journal in 1890 picks up the story:

Beethoven dedicated the sonata in the first instance to a violinist named Bridgetower, well known in London; and Bridgetower played the violin part so beautifully that Beethoven, hearing it for the first time, embraced his friend ‘with effusion.’

The London Evening Standard adds that due to delay in composition, Bridgetower was forced to play the sonata in concert ‘at sight, from Beethoven’s not over clear autograph.’ So this sonata should have been known to history as the Bridgetower Sonata, as it was written for and initially dedicated to the violinist.

Nottingham Journal | 15 April 1890

But the Nottingham Journal records why this particular Sonata became known as the Kreutzer Sonata, named after a man Beethoven ‘had never seen:’

Soon afterwards the composer found that his favourite violinist was making love to the very woman whom he at that moment cared for above all others. He then suppressed the original dedication, and inscribed the sonata to Kreutzer, who, but for this accident, would now scarcely be known.

Samuel Coleridge-Taylor

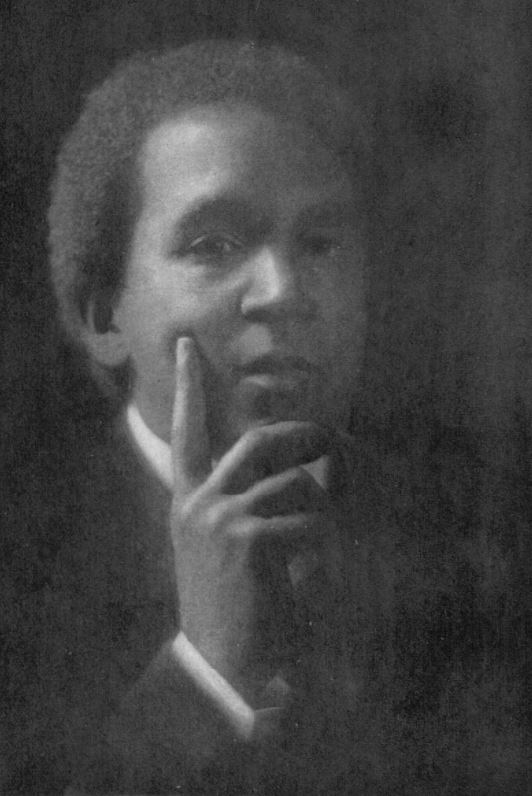

We move now to look at composer Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, who like George Bridgetower, saw early success in his life. Born in 1875 to an English mother, Alice Hare Martin, and a doctor father, Daniel Peter Hughes Taylor, who came from Sierra Leone, he studied at the Royal College of Music from the age of 15.

By his early twenties Coleridge-Taylor was already making his mark on the music world. As the Western Evening Herald remarks, it was his ‘setting of Longfellow’s Hiawatha’ that ‘gained for him very considerable popularity.’ Another violinist, in the tradition of Emidy and Bridgetower, in 1900 he was being lauded as one of Britain’s ‘best composers of the younger school.’

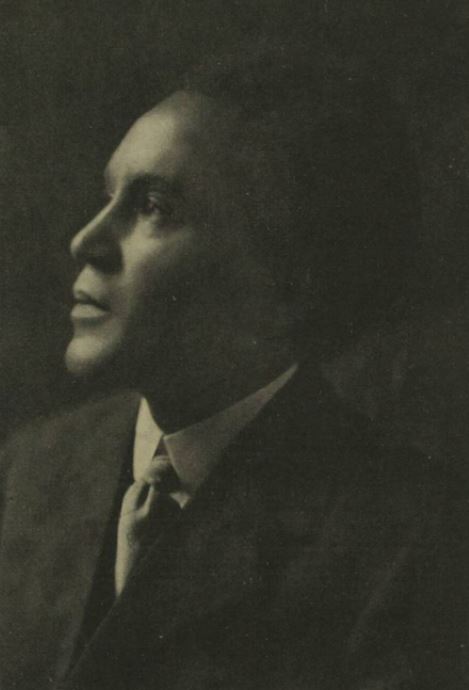

Sameul Coleridge-Taylor | Western Evening Herald | 3 October 1900

His success took him to America, where he was received by President Roosevelt at the White House, a highly unusual occurrence for a man of African descent.

Tragically, Coleridge-Taylor’s career and life was cut short when he died from pneumonia aged only 37 in 1912. The Illustrated London News reports how he was at the time ‘composing a ballet of Hiawatha‘ and remembers how the musician was ‘very popular as an adjudicator at competitive choral festivals, and as a teacher.’

Samuel Coleridge-Taylor | Illustrated London News | 7 September 1912

Coleridge-Taylors’s tragic early death provoked an outpouring of grief, and demonstrated how popular he had been in life, whilst he faced the multiple challenges of being a pioneering Black musician.

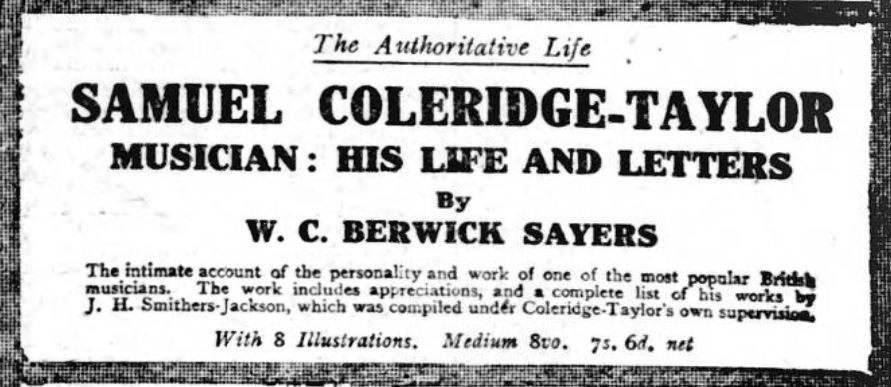

The Bystander describes the ‘irreparable loss to British music‘ that Coleridge-Taylor’s death caused, whilst three years later W.C. Berwick Sayers released a biography of the musician, offering an ‘intimate account of the personality and work of one of the most popular British musicians,’ according to the Birmingham Daily Gazette.

Birmingham Daily Gazette | 29 October 1915

Truth carried an eye-opening review of the biography, which revealed how Coleridge-Taylor was ‘never allowed to forget his origin,’ and how he faced ‘grotesque rudeness’ in relation to his race. But Coleridge-Taylor tried hard to not let such racism affect him, as he was ‘such a perfect gentleman as to be incapable not only of hurting the feelings of others, but even of allowing others to see that they had unconsciously hurt his.’

The review also notes how Coleridge-Taylor had to surrender his own cultural identity to the prevailing tastes of the day – providing ‘for one British festival after another the kind of music which suited their taste rather than his own genius.’ But faced with ‘difficulties, discouragements, and disappointments…bright and brave was the face he always turned towards his friends.’

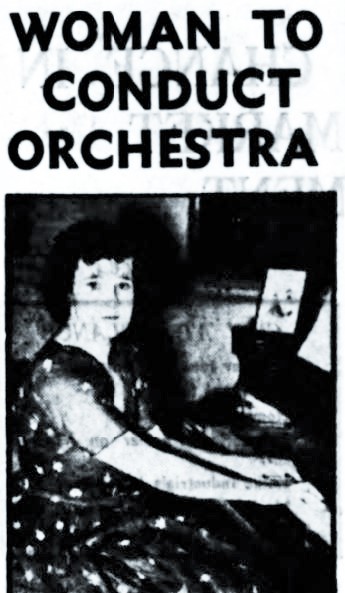

And Coleridge-Taylor’s legacy endured. Like Joseph Emidy, his children Hiawatha and Avril followed in his musical footsteps. In 1938 the Birmingham Daily Gazette reports how Avril Coleridge-Taylor was ‘shortly to leave for America to conduct the Boston Symphony Orchestra,’ having been the ‘first woman to be invited to conduct a band of the Royal Marines.’

Avril Coleridge-Taylor | Birmingham Daily Gazette | 25 August 1938

And in 1960 she returned to Croydon, where Coleridge-Taylor had lived, to meet with the Henry Wood Gramophone Society. Avril took with her a ‘specially made private recording’ of one of her father’s arrangements, this audience being the first to ever hear it, keeping her father’s legacy alive as she did so (Norwood News, 23 September 1960).

Perhaps the carving on Coleridge-Taylor’s memorial headstone, at Bandon Hill, composed by poet Alfred Noyes, is the best summing up of his musical and cultural impact (Norwood News, 31 May 1913):

In Memory of Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, who died on September 1st, 1912, at the age of 37. Bequeathing to the world a heritage of an undying beauty. His music lives. It was his own, and drawn from vital fountains. It pulsed with his own life. But now it is his immortality. He lives while music lives. Too young to die – his great simplicity, his happy courage in an alien world. His gentleness, Made all that knew him love him. Sleep, crowned with fame, fearless of change or time.

Samuel Coleridge-Taylor | The Bystander | 11 September 1912

Evelyn Dove

Like Coleridge-Taylor, singer and performer Evelyn Dove was born to a father from Sierra Leone, and an English mother, in 1902. Studying at the Royal Academy of Music, Evelyn Dove entered the cabaret and revue world of the 1920s.

In 1925 she travelled across Europe, the United States, and Russia, where she even reportedly performed in front of Stalin. Her appearance at Maskelyne’s in 1926 is noted in the Westminster Gazette, where she sang ‘spirituals.’

Evelyn Dove | Westminster Gazette | 11 June 1926

Evelyn Dove’s main British success was to come during wartime, as she became a fully fledged radio star. Six months before the war broke out, the Burnley Express writes of her visit with Rollin Smith to the BBC Studios to perform in ‘Mississippi Nights,’ and of the ‘immense success she enjoyed in New York.’

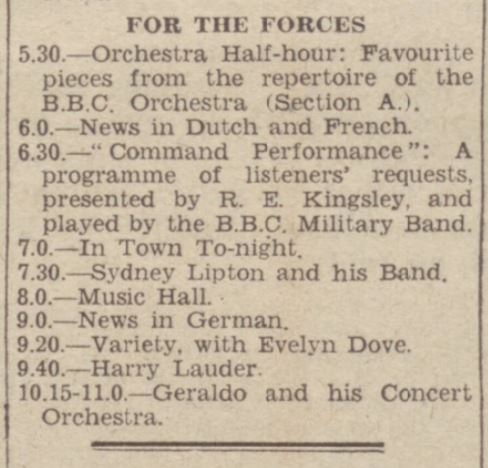

Throughout the Second World War, Dove is noted as appearing in many radio schedules – for example in December 1940 she is scheduled to perform ‘Variety‘ at 9.20pm ‘For the Forces’ (Coventry Evening Telegraph).

Coventry Evening Telegraph | 28 December 1940

Indeed, Dove became something of a forces’ sweetheart. Much attention was drawn to her visit to the small Gloucestershire village of Gretton in 1946, where many visitors were ‘intrigued to the identity of a…lady of considerable vivacity and charm.’ The Gloucestershire Echo revealed this to be none other than ‘well-known stage and radio star Evelyn Dove,’ who was caravanning with then husband Major Peter Webb in the Cotswolds.

Sadly, Dove’s career began to fade from that point onwards, and she passed away aged 85 in 1987. But Evelyn Dove will be remembered as a trailblazer for Black British women, making a name for herself like no other Black woman in Britain had done up to and including that time.

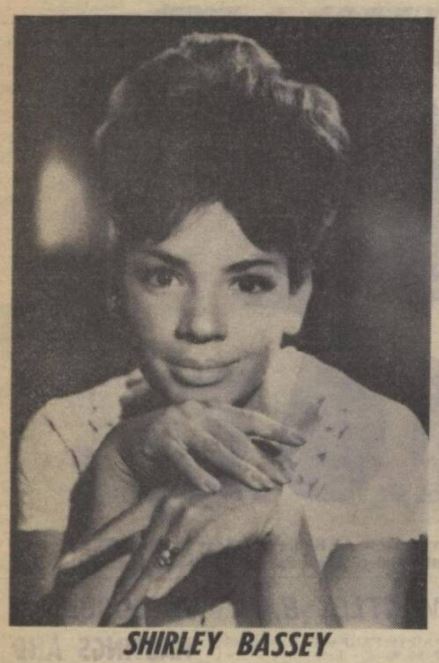

Shirley Bassey

And singer Shirley Bassey was to continue in the footsteps of the trailblazing Evelyn Dove. Born in Tiger Bay, Wales, to a Nigerian father and English mother in 1937, her singing career began in the early 1950s.

The Tatler in 1956 records her debut ‘as a cabaret artist at the Cafe de Paris,’ after she had made her breakthrough appearance in the Al Read show at London’s Adelphi Theatre. As a Black cabaret performer, the inevitable comparisons were drawn with Josephine Baker, of which ‘Miss Bassey shows all the promise and artistry.’

‘A New Star from Wales Sparkles’ – Shirley Bassey | The Tatler | 24 October 1956

But The Tatler notes the ‘electric force of her personality,’ marking her as one to watch. And of course, Shirley Bassey’s star was to rise and rise. By 1964 industry newspaper The Stage is writing how she is ‘the only British girl to crack the international cabaret market on a mammoth scale.’

The Stage, however, does not praise her talent, but rather, her ‘heart.’ Peter Hepple writes how that when ‘she sings, it is with every fibre of her being.’

But Shirley Bassey no doubt had it (and still has it) all – heart, talent and charisma. Two years later in 1966 she topped the US charts with the James Bond theme song Goldfinger. She was to hit the heights of the success in the 1970s with eighteen top albums in the British charts and was made a Dame Commander of the British Empire in 2000, for her services to performing arts.

Throughout the month of October we will be celebrating Black History Month at the British Newspaper Archive. Watch out for posts across our social media channels and more blogs celebrating Black historical figures. Our sister site Findmypast will also be celebrating Black History Month, showcasing useful resources for discovering Black history and genealogy.

Meanwhile, you can make a start researching Black history here on the British Newspaper Archive – what stories can you discover?