As part of our history of law and crime month on The Archive, we are delighted to featured a very special guest post by author and former probation officer Martin Baggoley, who has written extensively on the history of crime and punishment.

In this guest post, Martin describes how he used The Archive to research the tragic topic of infanticide in Victorian Salford, a desperately sad chapter in Britain’s crime history. So read on to discover the methods that Martin used in his research, and to find out about his discoveries.

Want to learn more? Register now and explore The Archive

I write on the history of crime and punishment, especially during the Victorian era and the British Newspaper Archive is an invaluable source of information. For instance, most murders went largely unnoticed in the national press, but a local newspaper would cover the crime from the discovery of the body, the inquest, the investigation, the trial and if appropriate, the execution of the murderer, which until 1868 would have been carried out in public. Recently, I have been researching into infanticide during this period, including the impact of the New Poor Law reforms of the 1830s and local newspapers have provided a wealth of information.

In the early years of the nineteenth century a single pregnant woman was required to advise the local parish officials and name the putative father, who became responsible for the financial support of the mother and child, if they did not marry. Failure on his part to do so could result in his imprisonment, but the parish would support the mother and child for as long as payments were not made.

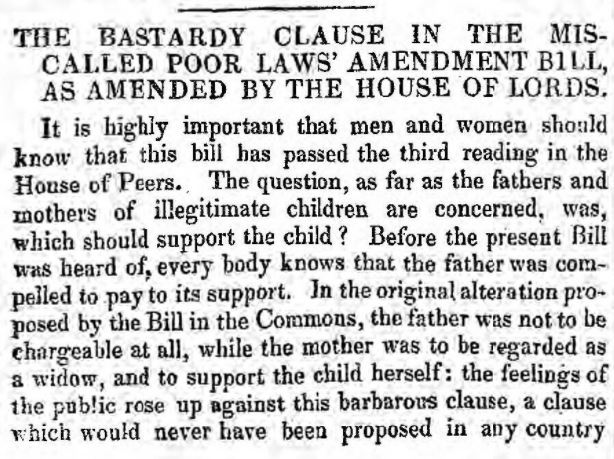

However, that all changed with the introduction of the Bastardy Clause of 1834, which had an immediate and dramatic impact on the lives of unmarried women who gave birth to illegitimate children. Henceforth, a single mother’s plight was now viewed as being the result of her own promiscuity and the father was absolved of all responsibility for the child’s upkeep.

Poor Man’s Guardian | 16 August 1834

Victorian England could therefore be a harsh and unforgiving place for a single mother if she did not receive support voluntarily from the father and if abandoned by her own family. She would find it almost impossible to find work and alone and destitute, her options were limited.

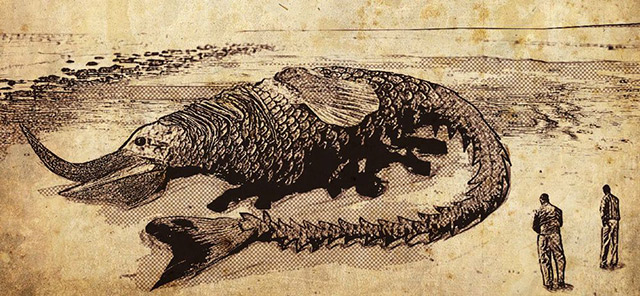

Before giving birth she might choose to have an abortion, but this was expensive, illegal and dangerous. After the baby was born she could enter the dreaded workhouse or abandon the child, possibly at the doors of a church, hoping a good home would be found for her baby. Furthermore, it was against this backdrop that baby farmers emerged and these were women who for a fee, promised to look after the child or find him or her a good home. However, once the mother’s weekly payments stopped, as they invariably did after a short time, the child would be murdered by the baby farmer or allowed to die through neglect and lack of food. The mother often realised this might happen, but took a chance on there being a more positive outcome. It also freed her from the responsibility of murdering the baby with her own hands.

‘Baby farming at Brixton’ | Illustrated Police News | 25 June 1870

One other course of action was for the mother, perhaps with the assistance of the father, to murder the baby, often within minutes of giving birth and following the reforms, there was a significant increase in the crime of infanticide. One particularly sad feature of this was the regular discovery of children’s corpses, obviously the victims of foul play. Some perpetrators were caught and punished, but many of the bodies remained unidentified and their murderers never traced.

This phenomenon became the object of my research and I decided to focus on the impact on Salford, a place in which I have a special interest. In the closing years of the nineteenth century, my great-grandfather, Constable Hugh Chesworth served in the town’s police force and seventy-five years after he retired I started my career as a probation officer there.

The Archive does not yet include Salford’s main newspaper, but Manchester which shares a common border with the town, has seven which cover its neighbour. Five of these span the years I was interested in and are; Manchester & Salford Advertiser (1837-48), Manchester Courier and Lancashire General Advertiser (1825-1916), Manchester Daily Examiner & Times (1856-1894), Manchester Evening News (1870-1958) and Manchester Times (1828-1900).

When looking for information, I faced an immediate problem as there are no victims’ or murderers’ names and without the archives, it would have been a daunting task to discover many details; however, this was easily overcome. In SEARCH TERM I entered ‘inquest’ and ‘Manchester’ under PUBLICATION PLACE; as for the PUBLICATION DATE, rather than choose 1834 to 1901, I searched in blocks of five years, so initially this was 1834 to 1839 and I asked any results to be given from the earliest date. Within a relatively short time I had eighteen positive results.

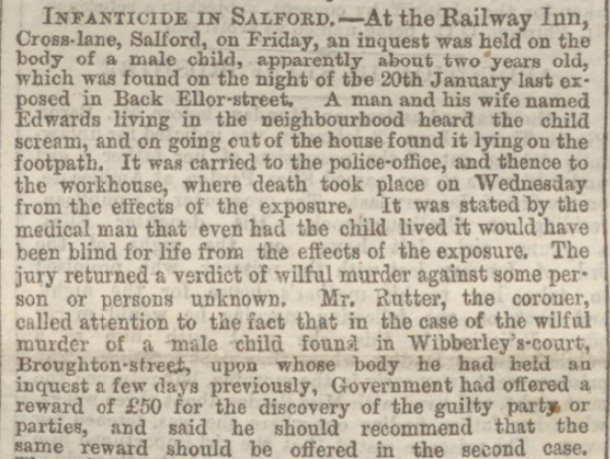

I have included three of these finds below, the first of which describes the death of a two year old, which serves to confirm that a child remained at risk should a mother’s circumstances worsen over a longer period. The screams of this victim were heard and he was taken to the workhouse for treatment. He survived for several weeks before eventually dying. The coroner was clearly concerned at the number of children being murdered, given his closing comments. (Manchester Courier, March 16th 1867).

Manchester Courier | 16 March 1867

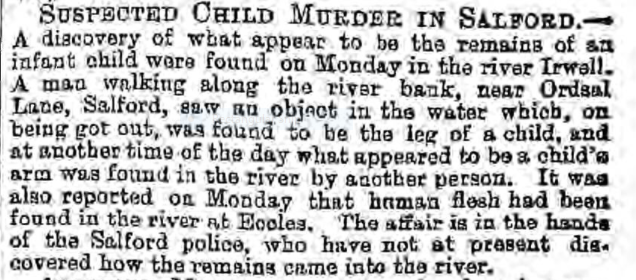

The second report describes finding the remains of a baby, who had been dismembered. They were discovered in the River Irwell over the course of one day. Firstly a leg was retrieved from the River Irwell and later an arm and a quantity of flesh. (Manchester Times, September 6th 1884).

Manchester Times | 6 September 1884

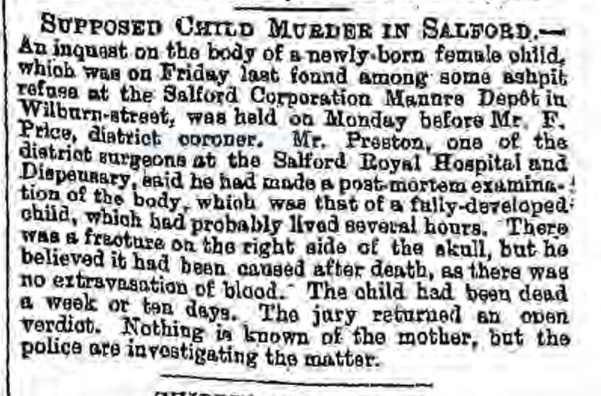

The third case concerns the discovery of a newly born baby girl at the Salford Corporation Manure Depot, a place, possibly chosen in the hope the body would not be found. (Manchester Times, February 28th 1885).

Manchester Times | 28 February 1885

As for the future, I intend looking into minor crimes and those who committed them in the nineteenth century in a particular city or town, possibly Salford! What would be a huge task will fortunately be made easier by reading the weekly reports in most local newspapers of the area’s police courts, which will no doubt once again prove to be a valuable source of information.