This week at The Archive we have added 46,718 brand new pages to our collection, with three brand new newspaper titles joining us in all. Two of our new titles illuminate the pan-Africanism movement of the early twentieth century, telling the story of the struggle against British colonial rule. Meanwhile, our new title of the week hails from London’s East End.

So read on to discover more about our new and updated titles of the week, as well as to find out about Cecilia Amado Taylor, a nurse from Sierra Leone who worked at the Endell Street Military Hospital during the First World War.

Register now and explore the Archive

We’re delighted to welcome our first new title of the week to The Archive, which is the African Telegraph and Gold Coast Mirror. Despite its name, the African Telegraph and Gold Coast Mirror was published in London from 1914. However, as academic Professor K.A.B. Jones-Quartey noted in his survey of the Gold Coast press, the African Telegraph and Gold Coast Mirror was a ‘child of both worlds.’ Jones-Quartey goes on to describe how:

It was printed in London in technical perfection, but was sponsored in Accra, and was lavishly illustrated with pictures from the then Gold Coast while at the same time carrying a wide coverage of West African affairs.

The Gold Coast, as the country was then known, was a British Crown colony on the Gulf of Guinea, in West Africa. It consisted of four different jurisdictions, all of which were under the administration of the Governor of the Gold Coast. And although the colony was officially founded in 1821, the legacy of colonialisation in the Gold Coast was a lengthy one, with the Portuguese having arrived in the region in 1471, followed by the British, Dutch, Danish, Prussian and Swiss.

After the arrival of such colonialists, the trade of enslaved persons from the Gold Coast became an important part of the local economy, with natural resources such as gold, timber and cocoa all being exploited.

Following the establishment of the British Gold Coast colony in 1821, the British government went on to purchase the surrounding territories of the Danish Gold Coast in 1850 and the Dutch Gold Coast in 1851, whilst invading and subjugating the local kingdoms of the Ashanti and the Fante. During the nineteenth century, the British fought four wars against the Ashanti people.

And so by 1901, the British colony of the Gold Coast incorporated all of the area, with colonialists building railways to take advantage of the area’s abundance of natural resources.

It was onto this landscape, therefore, that the African Telegraph and Gold Coast Mirror stepped, as the world began to witness the birth and the burgeoning of pan-Africanism, and various nationalist movements. The title was edited by John Eldred Taylor, a journalist from Sierra Leone, with contributions from Kobina Sekyi (1892-1956), a nationalist lawyer, politician and writer from the Gold Coast.

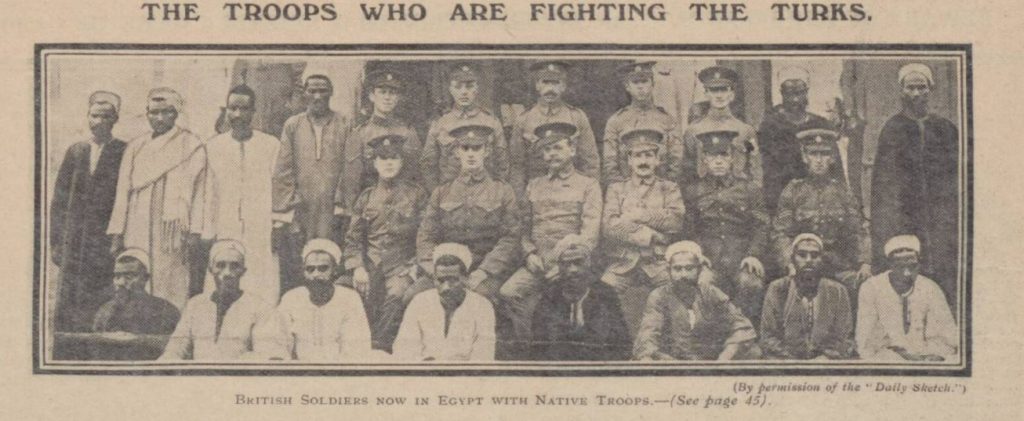

Alongside its editorial comment and other articles, the African Telegraph and Gold Coast Mirror contained a wonderful array of photographs, depicting life in West Africa, from pictures of dignitaries to those of Nigerian troops. Meanwhile, the newspaper dealt with a range of themes, addressing the nuances between the different languages to be found in West Africa, such as Yoruba, and English, as well as looking at issues surrounding colonialisation.

After the outbreak of war in August 1914, the African Telegraph and Gold Coast Mirror turned its attention to German affairs in Africa, in particular examining the ‘Failure of German Colonisation in Africa.’ Germany was portrayed by the newspaper as a cruel tyrant, in much the same way that British propaganda depicted its enemy. But the African Telegraph and Gold Coast Mirror maintained its focus on West African affairs, looking at, for example, banking in the region, and the ‘African Co-operative Corporation.’

The run of the African Telegraph and Gold Coast Mirror, however, was destined to be a short one, with publication halting in February 1915. Publication did not resume until December 1918, with the last issue appearing in 1919.

After the Gold Coast played an important role in the Second World War, the nationalist movement in the country grew and grew. Between 1951 and 1955 the Gold Coast shared power with Britain, until the Ghana Independence Act constituted the former Gold Coast Crown Colony as part of the new dominion of Ghana. As such, Ghana became the first African country to liberate itself from British colonialist rule, as such paving the way for other countries across the globe to follow suit.

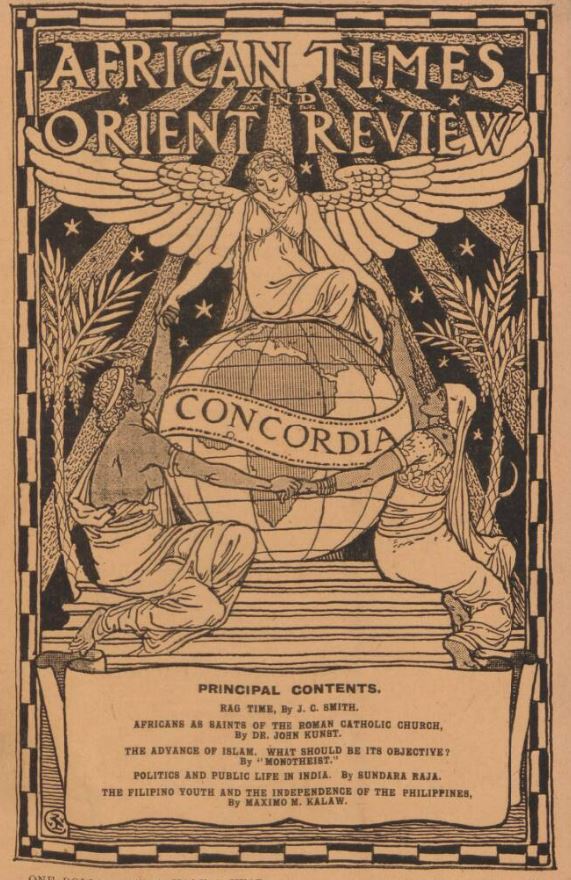

Another newspaper that agitated for pan-Africanism and the self-determination of colonialised countries was the African Times and Orient Review, which also promoted a pan-Asian agenda. The African Times and Orient Review was founded in 1912 in London by Sudanese-Egyptian actor and political activist Dusé Mohamed Ali (1866-1945). Dusé Mohamed Ali, who also was a playwright, journalist and editor, lived in England, until he relocated to Nigeria, where he found The Comet newspaper.

He was assisted in his new publishing venture by John Eldred Taylor, who also edited the African Telegraph and Gold Coast Mirror, although Dusé himself was responsible for the editing of the African Times and Orient Review.

The African Times and Orient Review was born out of the Universal Races Conference, which was first held at the University of London in 1911. The first issue of the newspaper in July 1912 noted how the conference:

…clearly demonstrated that there was ample need for a Pan-Oriental Pan-African journal at the seat of the British Empire which would lay the aims, desires, and intentions of the Black, Brown, and Yellow races – within and without the empire – at the throne of Caesar.

And so, the African Times and Orient Review was ‘devoted to the interests of the coloured races of the world,’ with financial backing for the publication being sourced from West Africans living in London at the time. Fante journalist J.E. Casely Hayford supported the newspaper, with support also coming from Francis T. Dove and C.W. Betts, both of whom were from Sierra Leone, and from Dr. Orguntola Sapara from Lagos, Nigeria.

The title was a revolutionary one, with its anti-imperialist stance, and its confrontation of the racism and discrimination that was endemic in British society and beyond at the time. It advocated for pan-Africanism, as well as for solidarity between African and Asian communities. The African Times and Orient Review became a forum for nationalism, and saw contributions from the likes of Jamaican political activist Marcus Garvey, Gold Coast nationalist lawyer Kobina Sekyi, and women’s rights activist Annie Besant.

Furthermore, the African Times and Orient Review aimed to target the political and academic elite of the day, seeking to ‘overcome misunderstandings and prejudice by providing accurate information to its readership on topics of interest to the British Empire.’ But its anti-imperialist stance meant that the publication was banned upon the outbreak of the First World War by the British government, the fear being that the newspaper would spread unrest in British colonies across the world.

However, the African Times and Orient Review was revived in January 1917, this time as a monthly publication, running until January 1920. From January 1920 it was renamed the African and Orient Review, before finally ceasing publication in December 1920.

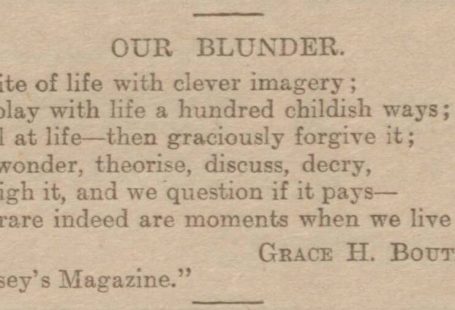

But what sort of content did the African Times and Orient Review contain? Well, from topical essays focused on issues in Africa, India and other locations, to political articles on a range of themes, the newspaper sometimes ventured towards light-heartedness, with the inclusion of a ‘coloured ladies’ beauty contest.’ For this competition, readers were invited to submit photographs. Indeed, the publication contained an array of illustrations and photographs, which filled its over fifty pages.

Another section was entitled ‘Man of the Month.’ The man of the month in April 1920 was Rabindranath Tagore, the Bengali polymath, who had returned his knighthood following the Amritsar Massacre, also known as the Jallianwala Bagh massacre, which saw hundreds of peaceful protestors slain by British troops.

With its international outlook, it was no surprise that the African Times and Orient Review claimed an international readership, with readers from the United States, the Caribbean, Africa and Asia. Its primary aim, fundamentally, was to educate, and to offer a British audience insight into the ‘aims and desires’ of African and Asian peoples.

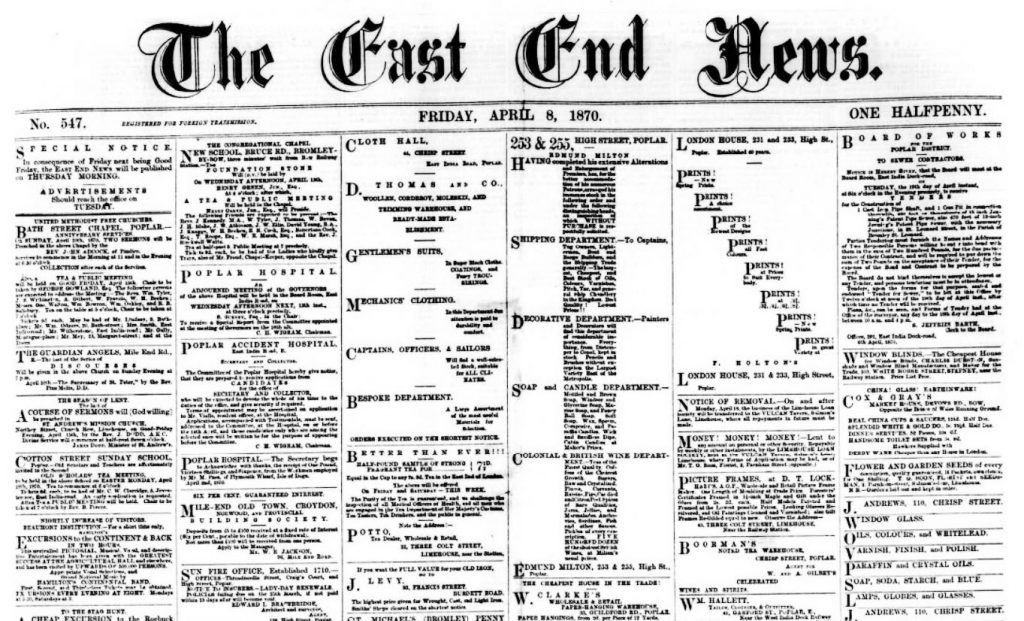

Our final new title of the week is the East End News and London Shipping Chronicle. Founded in 1859 as the East End News and Advertiser, the East End News and London Shipping Chronicle was published in Poplar, in London’s East End. At the cost of just one halfpenny, this politically neutral title circulated in London’s East End, throughout Poplar, Bromley, Bow, Limehouse, Ratcliff, Stepney, Mile End, Stratford, and Plaistow.

Initially appearing every Saturday, the East End News filled four pages and concentrated on local news, for example reporting on the latest from the Poplar Union Board of Guardians. Typical headlines ranged from ‘The Fatal Accident in the West India Docks’ to ‘Gambling in Victoria Park,’ whilst the newspaper demonstrated a particular penchant for cricket, reporting on the results of matches being played locally.

A robust local newspaper, the East End News contained a variety of advertisements, all of which reveal what life was like in Poplar at that time. The publication’s ads covered everything from the shops and apartments to be let in the area, to the jobs that were on offer.

By the 1880s, the East End News was appearing twice a week, on Tuesdays and Fridays, and was known to ‘circulate in the neighbourhood of the docks and water-side factories.’ Meanwhile, by the 1890s the newspaper had embraced its representation of docklands life, becoming known as the East End News, Shipping Guide and Dock Directory, before finally becoming the East End News and London Shipping Chronicle by 1899.

To this end, the newspaper contained a detailed dock directory, which listed the names of ships, their destinations and location within a certain dock. Docks typically covered by the East End News included the East India Dock, West India Dock, London Dock, St. Katharine Dock, Royal Albert Dock, Royal Victoria Dock, Millwall Dock, and Regents Canal Dock.

The East End News also featured a section entitled ‘Shipping Intelligence of Vessels to and From London,’ which gave the names of those ships arriving in and departing from London. And true to its local roots, the newspaper continued to give reports from such organisations as the Poplar Vestry and Mile End Liberal and Radical Association, whilst branching further afield to give a glimpse of ‘Places Worth Seeing,’ that is, ‘the business and pleasure resorts of the United Kingdom.’ Meanwhile, the newspaper also included serialised fiction, sport notes, which had expanded to include football as well as cricket, and a list of ‘entertainments’ in the area

We’ve updated one of our existing titles this week, namely Wales’s Monmouthshire Beacon, to which we have added the years 1912 to 1915.

Cecilia Amado Taylor and Endell Street Military Hospital

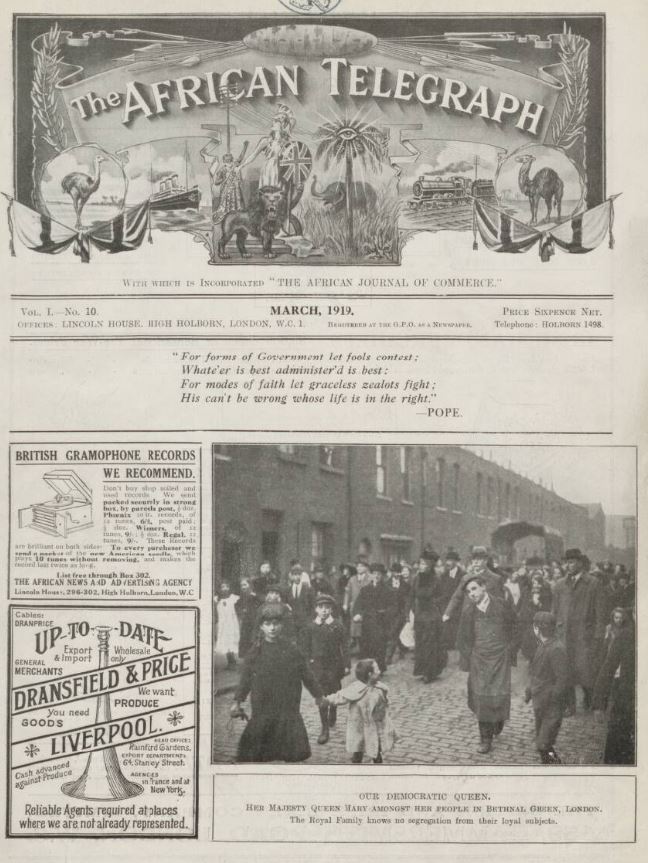

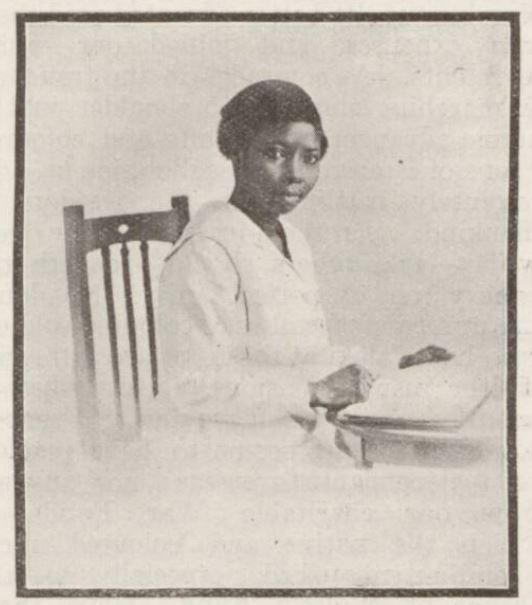

On 1 February 1919, the African Telegraph and Gold Coast Mirror featured a photograph of Nurse C. Amado Taylor, who had been working as a nurse at the Endell Street Military Hospital. We were intrigued, and wanted to find out more about Nurse Taylor, and her work at the hospital.

From the African Times and Orient Review some six years before, on 1 September 1913, we learn that Miss Taylor’s first name was Cecilia, and she was the ‘eldest daughter of Mr. Amado Taylor, Barrister-at-Law, of Freetown, Sierra Leone.’ At this time, Cecilia was ‘on a visit to England,’ and was staying with Mr and Mrs Daniel Wade at their home in Richmond.

The African Times and Orient Review notes how Cecilia ‘is an accomplished musician, and during her stay at Richmond’ she was due to ‘receive further instruction in the musical art from well-known professors.’

But Cecilia’s path had deviated from a musical one by 1919, as the African Telegraph and Gold Coast Mirror reveals. It tells us how:

Under the patronage of Her Most Gracious Majesty Queen Alexandra, Miss Taylor was admitted into the Endell Street Military Hospital where she has been doing her bit as a qualified nurse and midwife during the war.

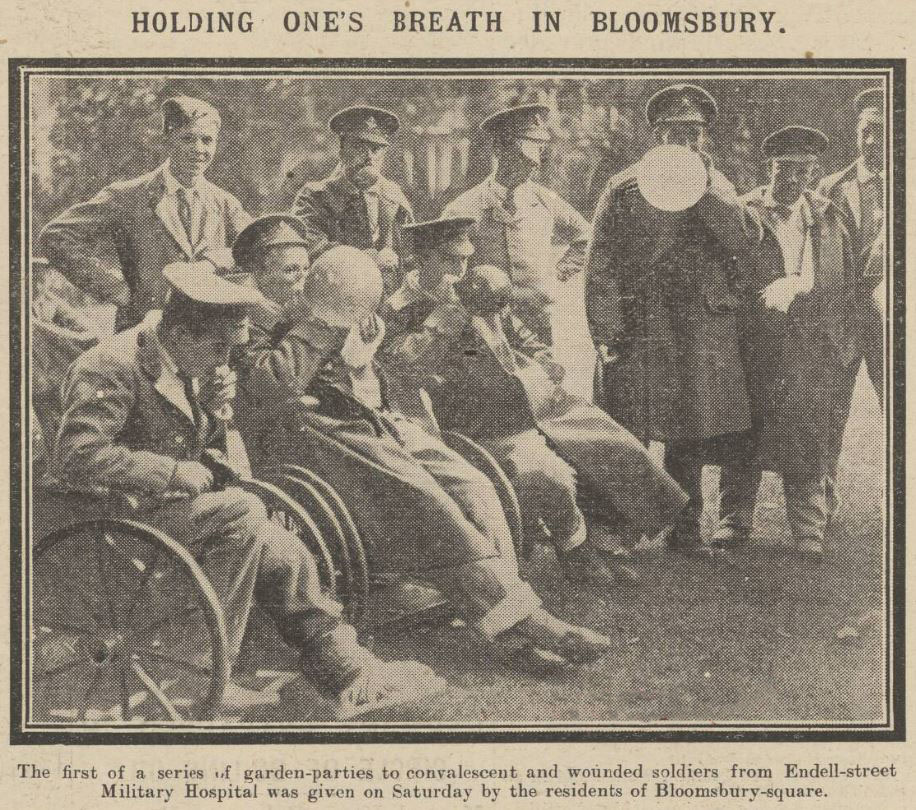

But what was the Endell Street Military Hospital, and what made it different from other hospitals at the time? The Endell Street Military Hospital, opened in May 1915, was mainly staffed by women, following Flora Murray and Louisa Garrett Anderson’s establishment of a hospital in France that was entirely staffed by women. Indeed, many suffragists worked at the Endell Street Military Hospital, to the extent that the establishment adopted the suffragette motto of ‘Deeds Not Words.’

The work of women at the Endell Street Military Hospital was highlighted by the press at the time, and particularly by women’s suffrage publications, such as Common Cause. On 28 July 1916 this title reminded its readers how ‘Endell Street Military Hospital is staffed entirely by women doctors.’

And Cecilia Taylor was just one of the women working at the hospital during the First World War and beyond. In August 1918, as the African Telegraph and Gold Coast Mirror tells us, Queen Alexandra, the mother of King George V, visited the Endell Street Hospital, accompanied by her daughter Princess Victoria and ‘their respective ladies-in-waiting.’

During this visit, Queen Alexandra ‘shook hands with Nurse Taylor, and asked her how she liked nursing, and whether she was happy.’ Cecilia answered the Queen’s questions, the Queen replying:

‘How beautifully you speak English! I am very pleased you wish to go back and help your own people.’

It was Cecilia’s aim to return to West Africa, as a ‘fully qualified medical practitioner.’ At the time of Queen Alexandra’s visit, and the publication of the article in the African Telegraph and Gold Coast Mirror, Cecilia was studying medicine. Cecilia, like the women she worked amongst, was a true trailblazer in the sphere of women’s medicine, but even more so, as she would surely have faced extra prejudice due to her race. As we move into October, and mark Black History Month in the United Kingdom, Cecilia Taylor’s name is one we can celebrate and remember.

New Titles

Title |

Years Added |

| African Telegraph and Gold Coast Mirror | 1914-1915, 1918-1919 |

| African Times and Orient Review | 1912-1914, 1917-1918 |

| East End News and London Shipping Chronicle | 1869-1938, 1940-1962 |

Updated Titles

This week we have updated one of our existing titles.

You can learn more about each of the titles we add to every week by clicking on their names. On each paper’s title page, you can read a FREE sample issue, learn more about our current holdings, and our plans for digitisation.

Title |

Years Added |

| Monmouthshire Beacon | 1912-1915 |

You can keep up to date with all the latest additions by visiting the recently added page. You can even look ahead to see what we’re going to add tomorrow.