As a result of the Second World War, over 60,000 British women married American soldiers (colloquially known as GIs), many of them returning with their new husbands to live in the United States once the war ended.

In this special blog, we are going to take a look at how the so-called GI brides were reported on by the press of the United Kingdom. We will examine how they faced warnings over their choice of husbands, and how they were prepared for their new lives across the Atlantic. We will also look at how they represented themselves in the newspapers of the day, with some GI brides expressing their thoughts in the correspondence sections of local and regional newspapers. Finally, we will also take a look at the British women who married soldiers of other nationalities – including Canadian, Australian, Polish and Czech servicemen – and their experiences in relation to the GI brides.

Register with us today and see what stories you can discover

‘Problems In Marrying U.S. Soldiers – Girls Warned’

One of the earliest mentions of women from the United Kingdom marrying American soldiers comes from Northern Irish newspaper the Ballymena Observer, on 19 June 1942. It was in Belfast that the first American troops arrived in Europe during the Second World War, arriving over a month after the United States declared war on Japan and were drawn into the global conflict.

So it was only fitting that one of the early mentions of American troops marrying women from the United Kingdom came from a Northern Irish newspaper. But the mention came in the form of a warning, which the Ballymena Observer reported as follows:

A memorandum prepared by Colonel C.E. Brand, Judge-Advocate of the U.S. Army, on the difficulties that may arise when an Irish girl marries an American soldier stationed here, was read at the services in Roman Catholic churches in Northern Ireland on Saturday.

The Roman Catholic Church in Northern Ireland wanted it to be made known that by marrying an American soldier, one did not automatically become a United States citizen.

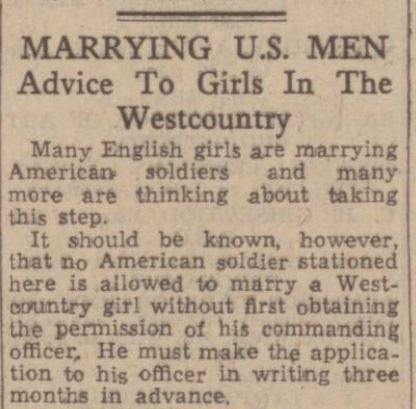

This was a theme that other newspapers returned to throughout the war, as American troops were stationed across the United Kingdom. The Western Morning News on 13 April 1944 gave ‘advice to girls in the West Country’ on this subject, describing how:

It should also be understood by local girls that marriage will not necessarily entitle them to American citizenship. If they try to accompany their husbands home after the war they may be held up at Ellis Island as aliens. Nor is there much likelihood of an English wife of an American soldier being allowed to travel with her husband if he should be sent out of the country, as he may be at a moment’s notice.

Not only would a GI bride not be entitled to American citizenship, nor entitled to swift passage back to the United States, her potential husband would also have to gain the ‘permission of his commanding officer,’ three months in advance of the impending nuptials.

A ‘Glad Hand for the GI Brides’

In September 1944 Curtiss Hamilton, writing for John Bull, provided a ‘glad hand for the GI brides.’ By this point in the war, it was reported that over ‘6,000 British girls have become the brides of American servicemen,’ a mere tenth of the final number of women who would become GI brides.

Hamilton explains to his readers how an ‘American soldier marries without the consent of his colonel only at the risk of severe penalties,’ but outlines how nine out of ten perspective couples saw ‘no real difficulties’ in their union being approved. Indeed, Hamilton notes how this slight delay in the formalisation of a couple’s relationship made it ‘difficult for couples to get married impulsively.’ He observes:

You have to be fond of each other to see the formalities through. Waiting means making sure. Thus some of the dangers of ‘war weddings’ are avoided.

Such a delay of three months also meant that any impediment to the marriage – such as an American soldier already being married – could be discovered well in advance of the ceremony itself.

Finally, Hamilton advised that any bride seeking a military wedding must first be married at a British registry office, as U.S. chaplains were not able to conduct marriages on British soil. Once the couple had been married at a registry office, they could then ‘have the religious ceremony conducted by the soldier-bridegroom’s chaplain in the Command church.’

‘How America Lives’

Once a woman became engaged to an American serviceman, or became a GI bride, help was on hand to prepare her for her new life in the United States. Although it was not yet known when she might be able to travel to America, steps were taken to make sure she would be ready once travel had been arranged.

Curtiss Hamilton for John Bull notes how the American Red Cross had given GI brides a small book entitled How America Lives, which provided information on ‘American ways of running a house, cooking, clothes, and so on.’

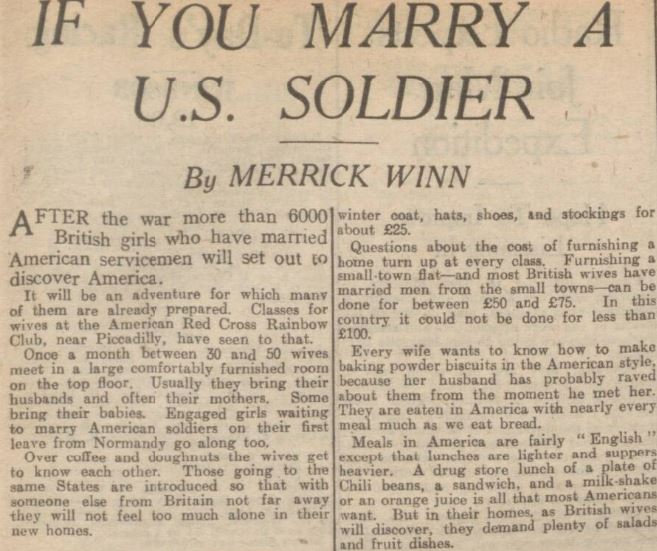

Indeed, the American Red Cross held special preparation courses for GI brides. Some of these classes were held at the famous American Red Cross Rainbow Club near Piccadilly every month. In September 1944 Merrick Winn for the Dundee Evening Telegraph reported how:

Once a month between 30 and 50 wives meet in a large comfortably furnished room on the top floor. Usually they bring their husbands and often their mothers. Some bring their babies. Engaged girls waiting to marry American soldiers on their first leave from Normandy go too.

Over ‘coffee and doughnuts,’ the women got to know each other, with ‘those going to the same States introduced so that with someone else from Britain not far away they will not feel too much alone in their new homes.’

The women meeting at the Rainbow Club in Piccadilly also had the opportunity to listen to lectures on different aspects of American life, which covered ‘social life, housing, health, education, cookery, clothes, housekeeping and babies,’ whilst also being permitted to ask a range of questions. ‘Easily the most popular question’ related to American citizenship, which had been at the centre of those warnings surrounding marrying U.S. servicemen earlier in the war.

Winn describes how to achieve American citizenship, the GI brides would have to ‘wait three years and then take an educational test to show that they can read and write and that they understand the groundwork of American history,’ facing such questions as ‘How many states are there, and how often is the President elected?’ Winn notes how the women looked ‘depressed at this news,’ but were soon cheered to learn that they would be able to take ‘naturalisation study courses’ in preparation for the test.

Other popular questions addressed the cost of living in America, from the cost of having a baby, to the cost of furnishing a home, to the cost of clothes, to the likely wage a woman could expect to earn. Although Winn notes how it costs ‘rather more than in Britain’ to have a baby, ‘the absolute minimum being about £35 for nursing home treatment for a fortnight,’ it was cheaper in the United States to furnish accommodation, and to buy ‘a complete outfit for a year.’ Wages in the U.S. were also ‘high,’ with a shop assistant expected ‘to earn about £3-£4 a week, and a shorthand typist up to £5 and secretaries about £6.’

Aside from economics, women were also apparently keen to find out ‘how to make baking powder biscuits in the American style, because her husband has probably raved about them from the moment he met her.’ The eating of these biscuits are compared by Merrick to the British consumption of bread. Finally, GI brides were told how:

Meals in America are fairly ‘English’ except that lunches are lighter and suppers heavier. A drug store lunch of a plate of Chili beans, a sandwich, and a milk-shake or an orange juice is all that most Americans want. But in their homes, as British wives will discover, they demand plenty of salads and fruit dishes.

‘A Land of Plenty’

The women that Merrick Winn describes in the Dundee Evening Telegraph also wanted to know what sort of welcome they would receive once they arrived in the United States.

They were told by the American Red Cross instructors:

‘Of course you’ll be welcomed […] You’ll have to be friendly from the moment you arrive […]There must be no ‘keeping yourself to yourself.’’

And the signs appeared positive. Curtiss Hamilton for John Bull reported how:

One thing seems certain. The brides are going to get a great welcome in their new country. They have already had enthusiastic letters welcoming them into the family. At least one has had an American wedding cake – made by her mother-in-law in Washington and sent over just in time for the wedding in Birmingham.

Meanwhile, the Essex Newsman in January 1945 reported on the experience of Mrs. Franz, who was formerly Miss Winifred Spooner of 55 Beehive Lane, Chelmsford. Winifred had worked as a bus conductor, and had married a sergeant in the 9th American Airforce, sailing to his parents’ home in Detroit in December 1944. She reported that her new life was ‘heavenly.’

Indeed, expectations were high, as the Essex Newsman noted:

They see the United States, where all hope to live one day, as a place of refuge from flying bombs. They know it as a land of plenty, where rationing as they know it does not exist. It is a lovely picture they see, embroidered with adventure and romance.

Merrick Winn, however, writing for the Dundee Evening Telegraph, notes how the American Red Cross worked to ‘debunk’ any ‘Hollywood idea of an American home.’ GI brides who dreamt of ‘floodlit swimming pools and singing cowboys are gently but firmly given the facts.’

Although not destined for a Hollywood lifestyle, the women who married American servicemen would be able to escape the austerity of Britain’s post-war years, as rationing continued and bomb-sites remained as semi-permanent scars on city landscapes.

‘Appeal to Brides’

It was little wonder then, that by the end of the war, GI brides were keen to travel with their husbands to America. They would have to wait, however, for the ships that would take them across the Atlantic, as the American government prioritised the return of its own servicemen.

Some, like Donesse Nancy Kuhn, simply could not wait. As the Nottingham Evening Post reported on 16 October 1945, 20-year-old Donesse stowed away on her husband’s ship, as he returned home. Donesse was lucky; she was given a temporary visa, and allowed to stay in the United States for a year.

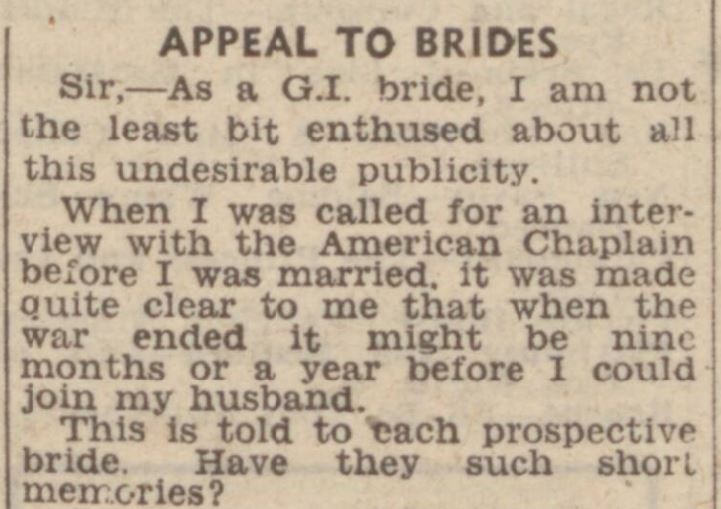

Other GI brides, like Donesse, were upset at the wait, although it had always been made clear to them that there would be a gap between their marriage and travelling to America. This upset caused one Glasgow GI bride to write to the Daily Record in October 1945. She described how:

When I was called for an interview with the American Chaplain before I was married, it was made quite clear to me that when the war ended it might be nine months or a year before I could join my husband. This is told to each prospective bride. Have they such short memories?

She ended with an appeal to her fellow Scottish GI brides:

Come on girls, be fair! Remember, you are entering a new country. Wouldn’t it be more to our advantage to make a friendly entry instead of antagonising the people we will have to live amongst? Don’t humiliate your husbands further by making your private affairs so public. Show that Scotch pride you cut your teeth on.

The GI bride from Glasgow was not the only one to write to the press about her situation as a wife of an American serviceman. One ‘British Bride’ from Warrington addressed the negative publicity surrounding the GI wives’ departure from Britain, writing to the Liverpool Evening Express in November 1945 and describing how out of the 50,000 GI brides waiting for transportation, 2,000 had participated in a demonstration over the perceived unfairness of their delayed travel.

Whilst she was ‘not in agreement with the attitude adopted by these brides,’ the writer from Warrington did understand their concerns, outlining how many of them had ‘young babies’ and no way of supporting them, following the discharge of their husbands from military service.

She was backed up by another GI bride from Widnes, who gave her name as H.M. Hodnette. Her letter was included in the same edition of the Liverpool Evening Express on 7 November 1945. She too had not made ‘a fuss about shipping space,’ and addressed the speculation that GI brides were being given priority over returning British prisoners of war. This was nothing but speculation; the American government were responsible for the transport of the GI brides, whilst the British government were responsible for the return of the POWs.

Addressing this speculation, Hodnette ended her letter by writing:

Like many more G.I. brides, no doubt, I am fed up reading stupid and insulting letters from our own English people, simply because we, too, having the longing to be with our loved ones and the homes they have prepared for us.

‘Golden Dreams’ of America

Another allegation levied against GI brides was their ‘golden dreams’ of America, and the life it would offer them. Both the women from Widnes and Warrington felt they had to defend themselves against such claims, claims that were levied by a letter writer under the name of ‘Ding.’

The GI bride from Widnes wrote:

I resent the unnecessary remark made by ‘Ding’ that ‘visiting America and Hollywood is perhaps a G.I. bride’s golden dream.’ Apparently he has forgotten there is such a thing as love, and, speaking not only for myself but for several friends married to American Service men, we are perfectly aware of what to expect in America, and I assure ‘Ding’ that our mentality is definitely not low, as he implies.

H.M. Hodnette was also stung into a response, describing how she had ‘no ‘golden dreams’ of all America being Hollywood.’

But for some GI brides and their husbands, the new life which greeted them in America was not set to have a fairy-tale ending. The news that a missing GI bride named Jean Carbone, who was aged nineteen and originally from London, had been found hit the front page of the Daily Mirror on 4 December 1945.

Jean had been found in Iowa at the ‘home of another man,’ a man who was not her husband, Lieutenant J.L. Carbone. Carbone and Jean had married a year before, and soon after the marriage, Carbone returned to America. This is where the troubles began. Jean’s mother Mrs. E.G. Gloor, of Hackney, told the Daily Mirror how:

Hardly had he gone before Jean began to fall out of love with him. It was her husband’s letters that did it; they were so unintelligent. Full of nothing but slushy sentiments. Jean couldn’t stand it. She wanted news of everyday life in America – what she was going to do.

Then Jean met Captain Darrell Beschen, who at 23 was a year younger than her husband. Her mother related what happened next:

She began to feel that she could no more live without Darrell than she could live with the other. Jean’s father and I knew Beschen well before he went back to America last month. We preferred him of the two. But we really did not want her to marry any American. We have pleaded with her that if she is not happy with Beschen she will come home to England at once.

It was at Beschen’s home Jean was found, and she was pregnant with his child. Jean had only been discovered because her husband had seen a photograph of her in the background of a picture of Mayor Edward Kelly arriving in Chicago by plane. Beschen had then sent Chicago police to look for her, and he swiftly requested a divorce.

Marrying ‘Foreigners’

And whilst there were over 60,000 GI brides in Britain, there were over 40,000 British women who married Canadian servicemen during the Second World War, with marriages also between British women and soldiers of a range of nationalities who found themselves stationed in Britain during the conflict.

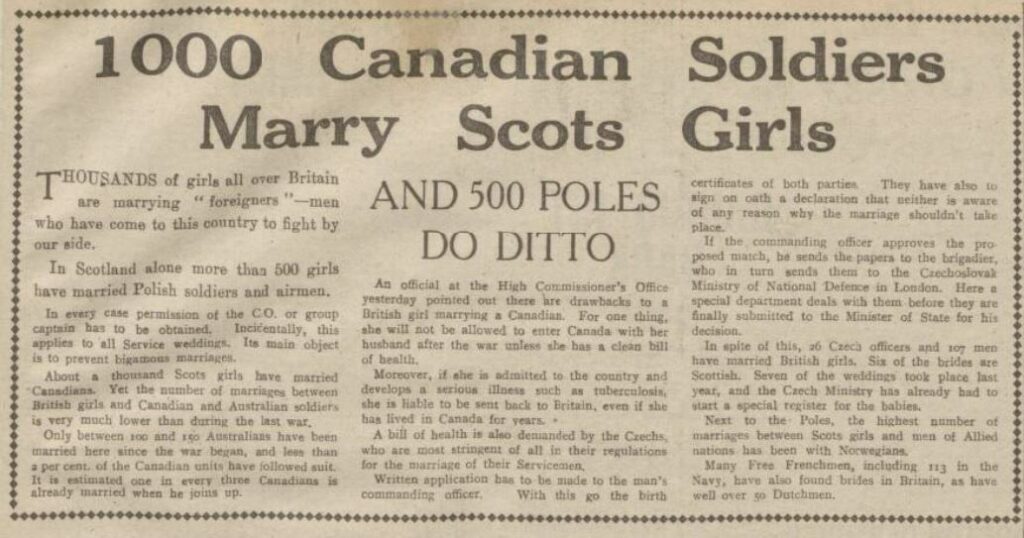

In December 1941 the Sunday Post wrote how ‘thousands of girls all over Britain are marrying ‘foreigners.” By this point in time, the newspaper reported how over 500 women from Scotland had married Polish soldiers and airmen, whilst over 1,000 women had married Canadian servicemen.

Again, like their GI bride counterparts, these women faced warnings, the Sunday Post describing how:

An official at the High Commissioner’s Office yesterday pointed out there are drawbacks to a British girl marrying a Canadian. For one thing, she will not be allowed to enter Canada with her husband after the war unless she has a clean bill of health. Moreover, if she is admitted to the country and develops a severe illness such as tuberculosis, she is liable to be sent back to Britain, even if she has lived in Canada for years.

But there was a loophole for the British brides of Canadian servicemen, as the Mid Sussex Times outlined in August 1942:

Girls who marry Canadian soldiers become Canadian subjects – and the National Service Act does not apply to Canadian subjects if they intend settling in Canada after the war. No girl who marries a Canadian soldier has to register for National Service. If she has registered she cannot be called up. This is a loop-hole which is causing some ill-feeling.

And whilst Canadian brides escaped war service, those women looking to marry Czech servicemen faced perhaps the most challenging requirements for all prospective brides. The Sunday Post in December 1941 reported how:

A bill of health is also demanded by the Czechs, who are most stringent of all in their regulations for their marriage of their Servicemen. Written application has to be made to the man’s commanding officer. With this go the birth certificates of both parties. They have also to sign on oath a declaration that neither is aware of any reason why the marriage shouldn’t take place. If the commanding officer approves the proposed match, he sends the paper to the brigadier, who in turns sends them to the Czechoslovak Ministry of National Defence in London. Here a special department deals with them before they are finally submitted to the Minister of State for his decision.

Despite such bureaucracy, by December 1941 26 Czech officers and 107 men had married British women, with six of the women being Scottish. Other wartime marriages were seen between women and men from Allied nations like Norway and Poland, whilst 113 Free Frenchman serving in the Navy had made matches with British women, and 50 men from the Netherlands had found brides in Britain.

And marriages weren’t just being solemnised in Britain. In August 1944 the Belfast Telegraph reported from Sydney, Australia, how ‘nearly 10,000 American solders have married Australian girls.’ At this point in the war, 1,000 Australian brides, accompanied by 200 babies, had left for the their new homes in the United States.

Conclusion

So alongside all the losses of the Second World War, new unions were being formed. The GI bride was a symbol of hope, a success story of love and glamour, as one nation stepped in to aid another. Such marriages also represented an important wave of migration to the United States, as well as to Canada and to Australia. Why not try following the stories of the GI brides in our newspapers, or search the records on our sister site Findmypast?