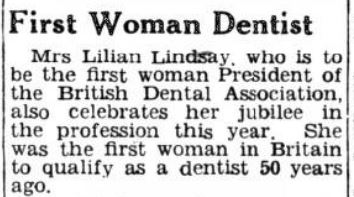

This March at The Archive we are celebrating inspiring women from history, who broke boundaries across different fields, whether they be medical, sporting, political and much more besides. We will be highlighting those inspiring women who broke the mould, and we will be showcasing the achievements of some lesser known women along the way, who deserve recognition for their trailblazing lives and careers.

And in this special blog, we will be looking at ten inspiring women from history who you may not have heard of, but most definitely should know about. From the first woman marine engineer, to the first woman to be a Mayor for London, we’ve delved through the pages of The Archive to highlight ten ground-breaking women from history who may not be household names.

How did we do this? We trawled The Archive, searching with the term ‘first woman.’ An apt and important phrase, which provided a huge insight into the achievements of women throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Indeed, the results cover many more women than the ten selected here, and provide an excellent starting point for research into the women who shattered stereotypes and paved the way for future generations.

So without any further ado, let’s begin our countdown of ten inspiring women from history. Their achievements are listed in chronological order.

Register now and explore the Archive

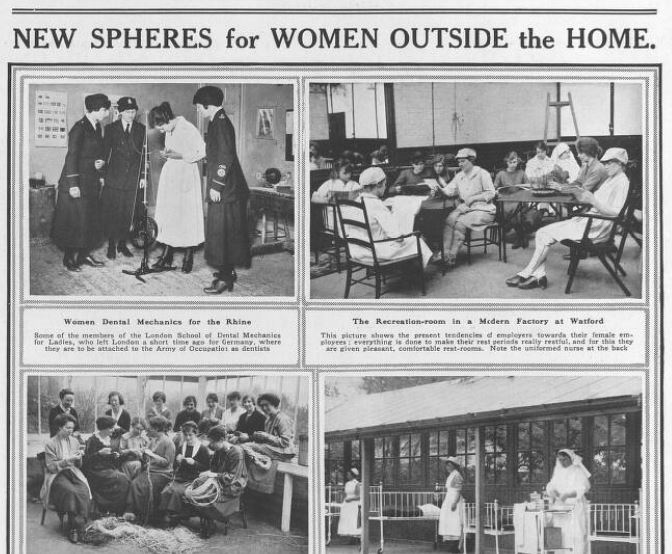

1. Lilian Lindsay (née Murray, 1871-1960) – First Woman Dentist To Qualify in Britain

Our first inspiring woman from history is London-born Lilian Lindsay, who in 1895 became the first woman to qualify as a dentist in the United Kingdom, having studied at the Edinburgh Dental Hospital and School. Other British women had travelled abroad to study dentistry, but Lilian was the first woman to qualify on British shores.

In October 1945 the Sunderland Daily Echo and Shipping Gazette noted how Lilian Lindsay was set to celebrate ‘her jubilee’ in the dental profession that year, being the ‘first woman in Britain to qualify as a dentist 50 years ago.’

Moreover, Lilian had just been made ‘the first woman President of the British Dental Association.’ She told a reporter how, fifty years since qualifying as a dentist, that there was ‘still a certain amount of prejudice against women dentists but not as much as she had to fight when she first chose her career.’

Her recipe for a good dentist was as follows: ‘a good constitution, good eyesight, and a skilful pair of hands.’

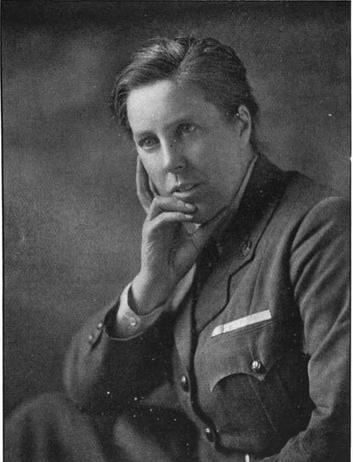

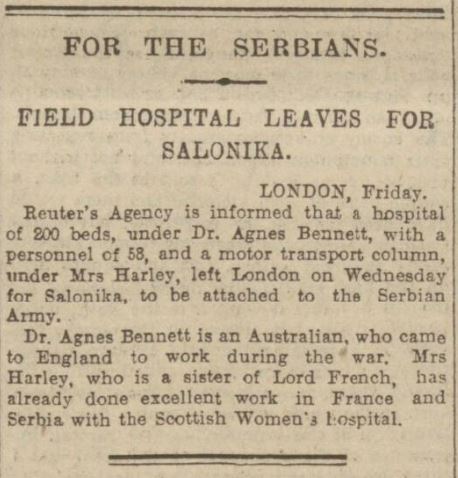

2. Agnes Elizabeth Lloyd Bennett (1872-1960) – First Woman Commissioned Officer in the British Army

Born in Australia in 1872, Agnes Bennett studied at the Edinburgh College of Medicine for Women, graduating in 1895. She then returned to Australia, and travelled on to New Zealand, where she worked as the chief medical officer at a maternity hospital. In 1911 she completed her M.D. in Edinburgh.

When the First World War broke out, Agnes worked with the British Army at war hospitals in Cairo. Looking back at this time, the Belfast Telegraph in January 1941 recalls how Agnes was ‘the first woman doctor to become an attested solider.’ She had ‘travelled to Egypt to offer her services as a doctor and there she was ‘signed on’ with the rank of captain in the R.N.Z.A.M.C.,’ thus becoming the first woman commissioned officer in the armies of Britain and her then Empire.

The Belfast Telegraph reports how she worked in Cairo for about a year, before she ‘then went on to London and took the famous Scottish Women’s Hospital, lock, stock and barrel, to the Balkans.’ The Western Daily Press on 5 August 1916 reported on this impressive mission:

Reuter’s Agency is informed that a hospital of 200 beds, under Dr. Agnes Bennett, with a personnel of 58, and a motor transport column, under Mrs Harley, left London on Wednesday for Salonika, to be attached to the Serbian Army.

It was a difficult posting at an isolated field hospital. By the summer of 1917 Agnes succumbed to malaria and was forced to resign her position. The Belfast Telegraph described how she ‘returned to New Zealand after the war,’ but in 1941 she returned to the United Kingdom ‘to study conditions in the Women’s Services with the object of advising those at home about sending New Zealand women over here to help.’

In 1948 Agnes was awarded the O.B.E. for her services to medicine in the First World War and to women’s and children’s medicine in New Zealand.

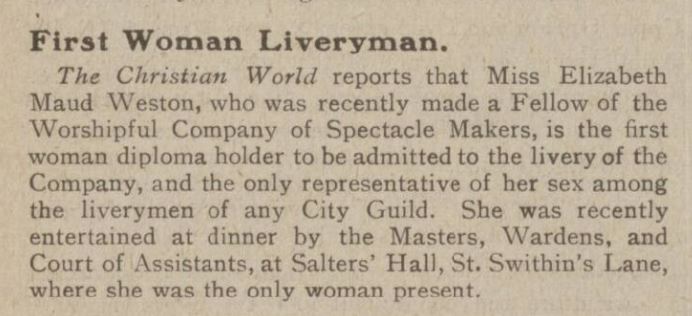

3. Elizabeth Maud Weston (1897-1993) – First Woman Liveryman

In February 1922 the Hinckley Times printed a short piece entitled ‘Honour for Local Optician.’ The local optician was Elizabeth Maud Weston, who at the age of 24 had become ‘the first lady diploma holder of the Worshipful Company of Spectaclemakers to be admitted to the Guild.’

The newspaper tells of how Elizabeth ‘gained the Company’s diploma for sight-testing in 1917,’ and how, after her father’s death in 1918, she had carried on his ‘business at Hinckley.’

Elizabeth made headlines again a few months later, when she was profiled in woman’s suffrage publication the Vote in April 1922. The article detailed how the optician was ‘the only representative of her sex among the liverymen of any City Guild,’ meaning that Elizabeth was the ‘first woman liveryman.’ A liveryman is a freeman of the City of London, with the right to vote in the election of the Lord Mayor, chamberlain, and other offices.

The Vote described how:

She was recently entertained at dinner by the Masters, Wardens, and Court of Assistants, at Salters’ Hall, St. Swithin’s Lane, where she was the only woman present.

Elizabeth went on to have a long life, and continued practising her craft. Thanks to our sister site Findmypast, we find her in the 1939 Register working as an optician. She passed away at the age of 96 in 1993.

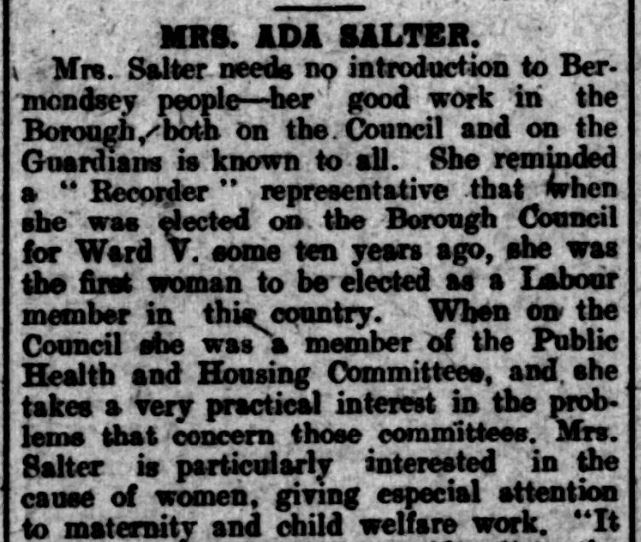

4. Ada Salter (née Brown, 1866-1942) – First Woman Labour Mayor and First Woman Mayor for London

Social reformer, environmentalist and devout Quaker Ada Salter was appointed Mayor of Bermondsey in 1922, making her, as the Vote described in the December of the same year, ‘the first woman Mayor for London, and the first Labour woman Mayor in the country.’ She ‘was also the first Labour woman to be elected on a London Borough Council.’

By 1919, this inspiring woman needed ‘no introduction to Bermondsey people – her good work in the Borough, both on the Council and on the Guardians is known to all,’ as detailed the Southwark and Bermondsey Recorder. Ten years before this she had been elected as a member of the Bermondsey Borough Council, making her ‘the first woman to be elected as a Labour member in this country.’

The Southwark and Bermondsey Recorder outlined her work at the council, where she was a member of the Public Health and Housing Committees. Ada took a ‘very practical interest in the problems that [concerned] those committees,’ being ‘particularly interested in the cause of women, giving especial attention to maternity and child welfare work.’

By 1922 Ada Salter had been appointed as Mayor for Bermondsey, and in December of that year she was interviewed by the Vote. She told the publication how:

As the first woman in London to be offered the position of Mayor, I am proud that I live and work in a borough, the elected representatives of which are prepared to choose an individual who belongs to what is sometimes described as the weaker sex. As a woman, I am naturally eager that the woman’s share in the responsibility of government should be a direct one.

She also outlined her strong pacifist beliefs in the publication:

Frankly, I am a convinced Pacifist. I know that some people feel that any effort connected with specially caring for the interests of the Army, Navy, or other war services, is a work set apart and particularly sacred. I do not share those views. There are only two paths before us as individuals, or as a nation. One path leads to other wars by efficient military, economic, educational preparedness for war. The other is traversed by those who desire disarmament by common consent of all the nations, and who demand definite organisation for peace. We cannot possibly follow both paths, but I feel that, in loyalty to my own and, and to the mothers and sisters of my race, it is my duty definitely to follow the second path. It has been, and still is, a thorny road to tread.

She ended her profile by stating how ‘the whole purpose of local government for us must be to make the borough in which we live a worthy home for us all.’ Ada Salter’s endeavours for local government made her an immensely popular figure, and throughout her career she campaigned for green areas that could be accessed by the working classes of the city, calling for a Green Belt around London, which granted by law in 1938. She passed away in 1942, having initially refused to leave Bermondsey, but was forced out when her home was bombed.

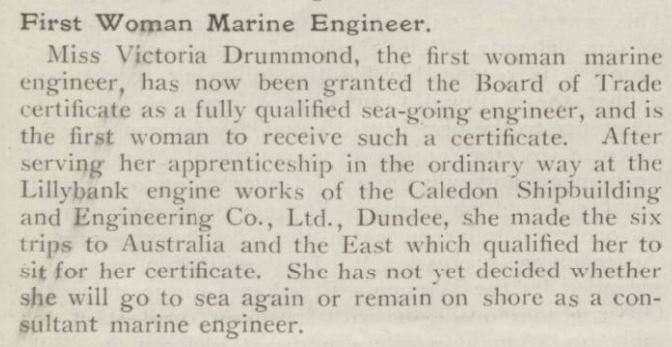

5. Victoria Drummond (1894-1978) – First Woman Marine Engineer in the United Kingdom

The 1920s were full of inspiring women, notable amongst them being Perthshire-born Victoria Drummond, ‘the first woman marine engineer.’ In 1926, the Vote reported how Victoria had ‘been granted the Board of Trade certificate as a fully qualified sea-going engineer.’ She was ‘the first woman to receive such a certificate.’

The Vote outlined how she had achieved her accreditation, describing how:

After serving her apprenticeship in the ordinary way at the Lillybank engine works of the Caledon Shipbuilding and Engineering Co., Ltd., Dundee, she made the six trips to Australia and the East which qualified her to sit for her certificate. She has not yet decided whether she will go to sea again or remain on shore as a consultant marine engineer.

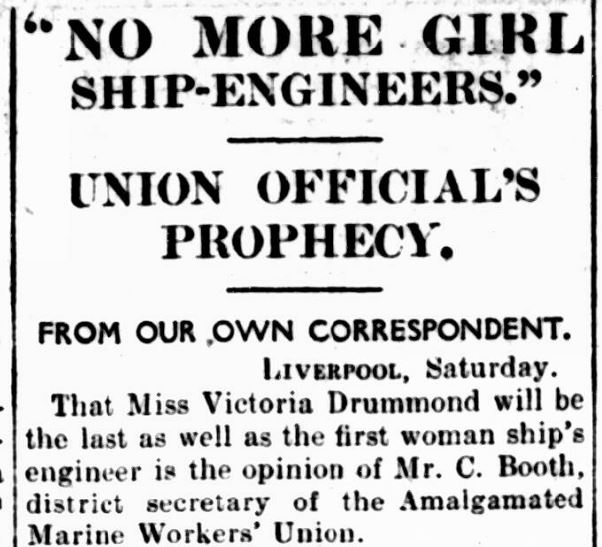

Her work as a marine engineer was met with some controversy, however. Mr. C. Booth, the district secretary of the Amalgamated Marine Workers’ Union, was reported by the Weekly Dispatch (London) in January 1923 as saying how ‘Miss Victoria Drummond will be the last as well as the first woman ship’s engineer.’ He went on to state:

‘The owners of the Blue Funnel Line allowed Miss Drummond to sail in the Anchises to enable her to complete her 18 months at sea and qualify to become a fully certified engineer, and there is not the least chance of their repeating the experiment. Women are no substitutes for men in the engine-room of a ship at sea…She is not likely to go to sea again, I should imagine.’

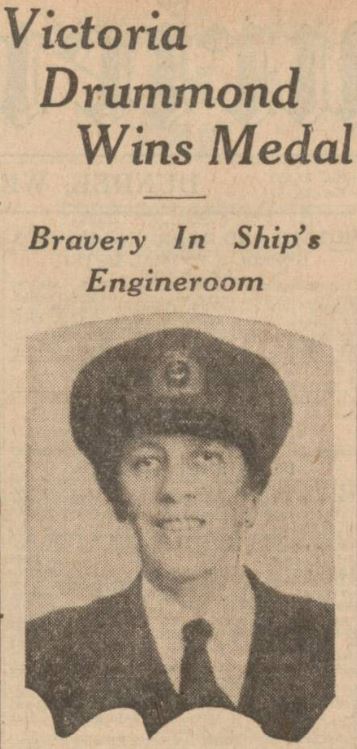

Such was the prejudice against Victoria Drummond, that her fellow crew members ‘were sworn to secrecy’ as to her very presence on board ship. But despite such detractors, Victoria did go to sea again. And in the Second World War she served as a Second Engineer on merchant vessels, and was integral to saving her ship when it was attacked in 1940. For her bravery, she ‘received the M.B.E. from the King’ in July 1941, as reported the Liverpool Daily Post, whilst the Dundee Courier in October 1941 described how:

Miss Victoria Drummond, ship’s second engineer, who took charge below when her ship was attacked 400 miles from land by an enemy aircraft, is awarded Lloyd’s War Medal for exceptional gallantry at sea.

The official account of her actions stated how ‘her conduct was an inspiration to the ship’s company, and her devotion to duty prevented more serious damage to the vessel.’

6. Mary, Lady Heath (1896-1939) – First Woman Parachutist in Britain

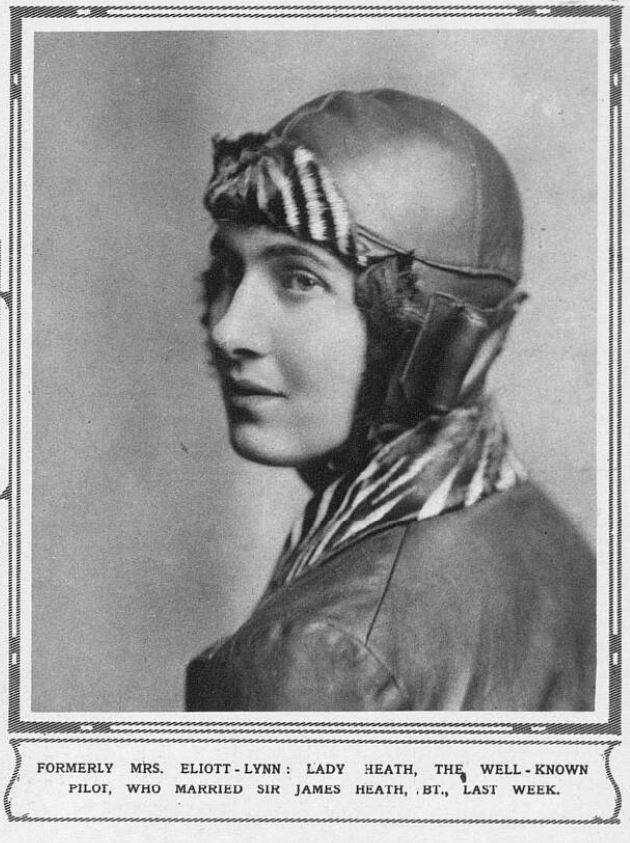

The next of our inspiring women is Mary, Lady Heath, who was born Sophie Catherine Theresa Mary Peirce-Evans in Knockaderry, County Limerick, who also made history in the 1920s. In April 1926 the Aberdeen Press and Journal reported on Britain’s ‘First Woman Parachutist,’ using Mary’s first married name of Mrs Eliot Lynn:

Mrs Eliott Lynn made the first successful parachute descent by a British woman at Hereford on Saturday, when she left an airplane at a height of 1500 feet and reached earth in 64 seconds. She failed in an attempt the previous day, owing to the machine having to make a forced landing.

In the 1920s Mary was a famous and acclaimed aviator. Here, the Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News in August 1927 waxes lyrical about her:

A good deal has been written in these notes just lately about Mrs. Elliot-Lynn. But she shows such abounding energy and endurance and such an amazing disinclination to rest on the many laurels she has already won, that it is perhaps not necessary to apologise for referring to her once again, after her exploits last week in Switzerland.

The article continues:

At the International Aviation meeting, at Zurich, she had the distinction of being the only woman pilot, the only owner pilot, and the pilot of the only British machine in the race for the St. Gall Cup, which she further distinguished herself by winning. Mrs. Lynn covered the course from Dubendorf, through St. Gall, Basle, Thun, and back to Dubendorf, a distance of about 200 miles in under three hours, winning by the big margin of nearly an hour. She also won the Basle Cup for the fastest speed from St. Gall to Basle.

Later that year, in October 1927, Mary was breaking records again. The Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News describes how:

Taking off from the Woodford Aerodrome, near Manchester, Mrs. Elliot-Lynn created a new altitude record the other day for light aeroplanes in her Avro-Avion. The flight was conducted under the auspices of the Royal Aero Club, and a height of 18,750 feet was attained.

The Irish aviator paved the way for other women fliers, including the likes of the more well-known Amy Johnson.

7. Esther Rickards (1893-1977) – First Woman Labour Alderman of London County Council

The next of our inspiring women is surgeon and politician Esther Rickards, who was born to a Jewish family in Paddington in 1893. In 1929 she was profiled by the Vote as the ‘First Woman Labour Alderman of the L.C.C.,’ an alderman being an often high-ranking member of a council, the council in this case being the London County Council.

The Vote describes Esther Rickards as being ‘among the younger women who fought for political enfranchisement,’ but also as being an ‘enthusiastic worker and an exceptionally clear thinker.’ Esther had trained as a doctor, and had obtained her Master of Surgery qualification in 1923, before being accepted as one of the first women fellows of the Royal College of Surgeons.

The Vote outlined her medical background in relation to her new role on the council:

Miss Rickards’ medical experience adds greatly to her value to such a body as the London County Council. For three years she has served as a member of the Mental Hospital Committee, and during that time she has fought strenuously for the admission of women to the staffs of mental institutions. As a result of agitation, in which men and women of all political parties have taken part, two women are to be admitted to the staff of each mental hospital – at present in junior positions.

Meanwhile, Esther Rickards was also serving on the Committee for Changes in Local Government, and the Housing Committee. For the latter committee, the Vote describes her as one of its younger members, but among its ‘most forceful.’

Some 45 years later, Esther Rickards was interviewed by Linda Christie for the Aberdeen Evening Express, in which she detailed her time as both a doctor and a suffragette. Indeed, Esther never wanted to be a surgeon, but a vet, however, this was not a pathway that was open to women at the time, and so instead she decided to study medicine.

She described her time as a suffragette, explaining how she:

‘…chained myself to the railings and all. I was never arrested, but my sister was thrown in prison twice. I got thrown out of St. Paul’s for protesting and out of a synagogue, and I protested with the others in the House of Commons. It was really very good fun, and there were good times. The suffragettes were in Holloway Jail, and we used to go and sing to them far into the night. Did you know that if you sing one hymn for every other song you can’t be moved on? – so that’s what we did.’

Esther labelled herself as a ‘violent suffragette,’ telling reporter Linda Christie:

‘…and this is the reason…if you don’t write this down I’ll never speak to you again…we became violent when we had six Bills given a second reading in the House of Commons and then they were refused time by the Government of the day to become law. That’s when we became violent.’

Later in life Esther Rickards was free to pursue her passion for animals, and most particularly dogs. It was that subject she discussed with the late Queen Elizabeth II when she received an O.B.E. for her work at St. Mary’s Hospital, Paddington, as Linda Christie recounts:

The Queen asked her what outside interests she had. ‘Dogs, ma’am,’ replied the doctor. ‘Oh!’ said the Queen with a note of delight in her voice, ‘Dogs!’ And then she said: ‘You’re the secretary of the Windsor Dog Show and write to me every year.’ ‘So we talked about dogs for 10 minutes, and never a mention of the hospital,’ Esther recalls.

8. Odette Myrtil (1898-1978) – London’s First Woman Dance Band Leader

The Vote has been an incredibly useful resource in helping us to uncover inspiring women from history, and in its pages from January 1931 we found mention of the ‘First Woman Dance Band Conductor.’ The publication details how ‘Miss Odette Myrtil, the well-known violinist and dancer, is the first woman to conduct a dance band in London.’

Odette Myrtil, an actress, singer and violinist, was born in Paris in 1898, and had some fifteen years before caused a stir in Britain. In July 1916 entertainment publication The Era labelled her as ‘The Discovery of the Year,’ with the Leicester Evening Mail penning in the same month:

A notable visitor to the Palace next week is Mdlle. Odette Myrtil, a Parisian musician and an Apache artist, a singer of quality to boot. Mdlle. Myrtil was born in a musical atmosphere, and at the age of nine was receiving lessons from the great Ysaye. She has been a star in the Parisian firmament for many years, particularly as a dancer, and is considered to have no equal as an exponent of the Apache school.

Already a ‘firm favourite,’ Odette was an practiser of ‘Apache’ dancing, a dramatic dance that arose from Parisian street culture. Odette would go on to become a success in many Broadway productions, whilst also starring in 28 feature films.

9. Elsie Dorothea Chamberlain (1910-1991) – First Woman Chaplain In The British Armed Forces

The penultimate of our inspiring women is Elsie Dorothea Chamberlain, a Congregational Church minister who was born in Islington, London. In March 1946 the Belfast Telegraph announced her appointment as the ‘first woman padre in the R.A.F.,’ a position that gave her the honorary rank of ‘squadron officer.’

Some ten years later in 1956 Elsie Chamberlain was again making history, with her appointment as ‘the first woman chairman of the Congregational Union,’ as reported the Bradford Observer. The newspaper notes how it was ‘the third time she had made history,’ detailing how:

…she was the first woman chaplain to the Forces, becoming a W.R.A.A.F. squadron-leader, and by her marriage to the Rev. John L. Garrington, Vicar of All Saints’ Hampton, Middlesex, she became the first Congregational minister to marry a Church of England clergyman.

And the new chairman did not mince her words when it was time to address the Congregational Union at Westminster Chapel, telling her audience how:

‘I have seen great church buildings in town centres – where all the world goes to and fro on its business – that display no sign of life, just locked doors, until all the world has gone home at night or at the weekend…Then, someone creeps out from under a stone and unlocks the great doors and a few people come from a distance, mostly into a dark back seat under a colossal, unused gallery. It is rather ludicrous, isn’t it?’

Elsie was advocating for services to be held on weekdays, to be more accommodating for the working and busy general population. During her career she also presented religious programmes on BBC Radio.

10. Margaret Grace “Peggy” Braithwaite (1919-1996) – Britain’s First Woman Lighthouse Keeper

The last of our inspiring women from history is Margaret Grace Braithwaite, known as Peggy, who was Britain’s first woman lighthouse keeper. Following in the footsteps of her father, who was also a lighthouse keeper, Peggy Braithwaite became the ‘principal lighthouse keeper of the Walney Island lighthouse, near Barrow’ in 1975, as reported the Sunday Sun (Newcastle) in July 1984.

Peggy had worked at the lighthouse for 35 years, and it was the same lighthouse her father had kept before her.

In July 1984 Peggy Braithwaite was ‘invested with the BEM by Princess Margaret at the Lakeland Rose Show at Holker Hall, Cumbria.’ The Sunday Sun (Newcastle) reported how:

The citation said she kept the lighthouse in ‘immaculate condition’ and on occasion pushed the light round herself all night when the mechanism failed. The Queen sent a message saying she was sorry she could not perform the investiture herself, but the award had been ‘so much earned.’

By April 1994, the Huddersfield Daily Examiner was reporting how Peggy was preparing ‘to switch off her lights for the last time this month.’ She had first gone ‘to Walney Lighthouse, Cumbria, as a child in the 1930s when her father was keeper,’ and was now about to leave ‘her cottage home at the lighthouse and move to Barrow-in-Furness to write her life story.’

Which of these pioneering women from history have inspired you the most? Who do you want to find out more about? Which other inspiring women can you uncover in the pages of our Archive today?