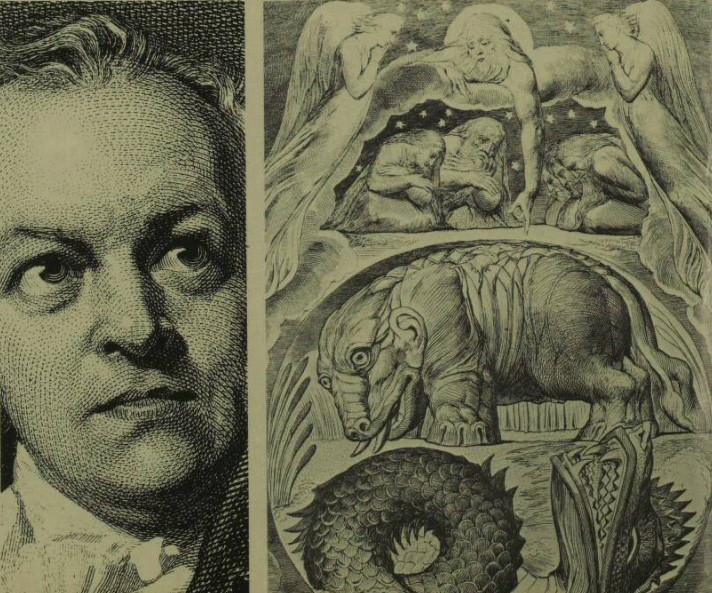

The work of poet, mystic and painter William Blake was largely unrecognised in his lifetime. The son of a dissenting hosier, Blake was born in London’s Soho in 1757, and was apprenticed to an engraver at a young age. Hostile to organised religion, he created an array of paintings and poetry, often inspired by his visions, before he passed away in 1827.

In this special blog, we will take a look at the evolving attitudes to the art of William Blake. We will trace his legacy through the pages of our newspapers, beginning during his lifetime, to the century after his death.

Register now and explore the Archive

In Blake’s Lifetime

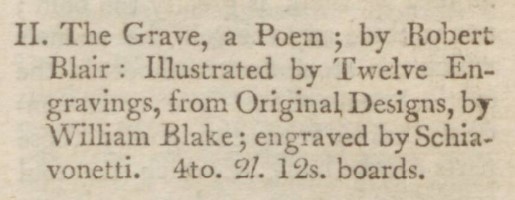

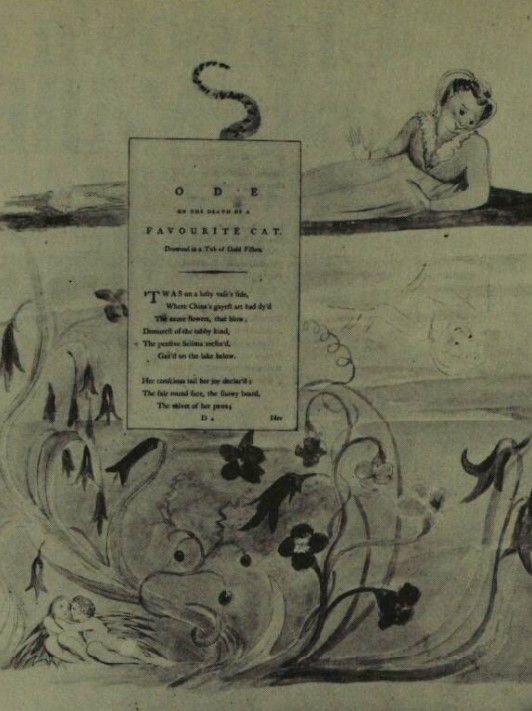

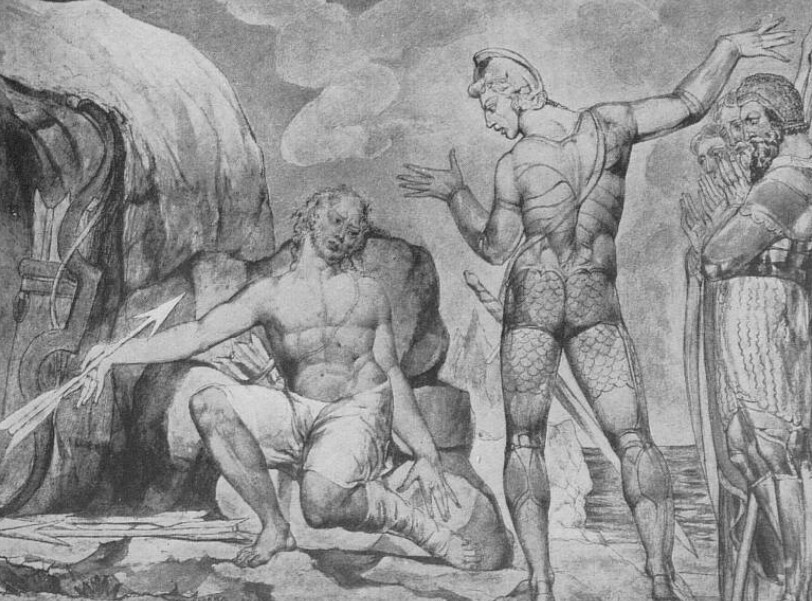

Searching through the pages of our newspapers, we found very few mentions of William Blake during his lifetime. This reflects how little known the artist and poet was whilst he lived, but we were able to find some mention of his illustrations from The Scots Magazine, in an article that was published on 1 November 1808.

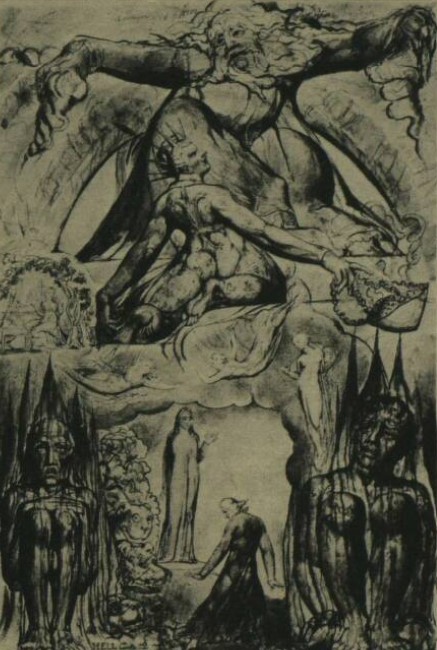

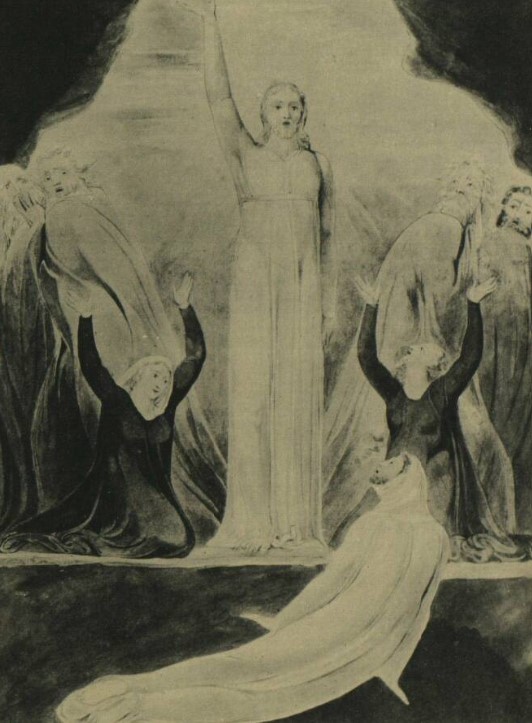

The work for which William Blake was most known whilst he lived was the illustrations he provided for Robert Blair’s poem The Grave. The Scots Magazine begins by identifying the ‘peculiar nature’ of the drawings, but the review does provide Blake with some praise:

The accuracy of the design, the faithful representation of the different parts of the human form, according to the various postures in which they are placed, are also, we understand, highly admired by connoisseurs. The subject is awful, yet attractive; it is one in which all must feel deep interest; and though man be a being naturally so bent on pleasure, there is yet a region of mystic gloom, thro’ which, in other moments he delights to expatiate.

Indeed, The Scots Magazine remarks how ‘we do not recollect to have any where seen so much genius united with so much eccentricity.’ High praise indeed for an artist who saw so little recognition during his lifetime, and for an artist who so rarely appeared in the pages of the press whilst he lived.

‘Blake Died Last Monday’

One of the next mentions in our newspapers of William Blake came in the days after his death, which occurred on 12 August 1827. On 18 August 1827 the London Evening Standard announced the news, emphasising the artist’s passing in italics – ‘Blake died last Monday!’ – and recognising the ‘piously cheerful’ way in which he had both lived and died.

This article for the London Evening Standard is an interesting one, as it declares how ‘few persons of taste are unacquainted with the designs of Blake,’ and how his work, specifically the illustrations for Blair’s poem The Grave, ‘was borne forth into the world on the warmest praises of all our prominent artists.’

It seemed to be, however, only such artists who were aware of Blake’s genius at the time. Sculptor John Flaxman (1755-1826) saw the ‘obscurity of Blake as a melancholy proof of English apathy towards the grand.’ And such apathy meant that William Blake lived in relative poverty, as the London Evening Standard outlined:

Blake [has] been allowed to exist in a penury which most artists, being necessarily of a sensitive temperament, would deem intolerable. Pent, with his affectionate wife, in a close back-room in one of the Strand courts, his bed in one corner, his meagre dinner in another, a rickety table holding his copper-plates in progress, his colours, his books, his large drawings, sketches, and MSS – his anlces frightfully swelled, his chest disordered, old age striding on, his wants increased, but not his miserable means and appliances: even yet was his eye undimmed, the fire of his imagination unquenched, and the preternatural, never-resting activity of his mind unflagging.

Blake, according to the article, ‘left nothing except some pictures, copper-plates, and his principle work, a Series of a hundred large Designs from Dante.’ This meant that his widow Catherine (1762-1831) was left ‘in a very forlorn condition.’ And with the artist’s death, would his work be remembered?

‘Who Was William Blake?’

Over forty years after the passing of William Blake, the Morning Post published a review of poet Algernon Charles Swinburne’s (1837-1909) essay on the artist and poet. The first item of business for the review, which was printed on 13 February 1868, was to ask ‘Who was William Blake?,’ a question that the writer anticipated would be called ‘forth from many a lip.’

Swinburne’s essay, amongst other works, marked a turning point in Blake’s legacy, as the Morning Post outlined. The article explains how the artist and poet ‘is now brought before us out of his repose of 40 years, to claim for the future a fame denied him in the past.’

But the writer for the Morning Post is not convinced by this revival of interest in William Blake, deeming his paintings to be ‘grotesque and perplexing.’ Indeed, the piece offers this rather damning conclusion:

That such a man was not known to his contemporaries can excite no wonder; but it is more surprising that we should be expected to accord the need which they withheld.

‘A Puzzle to Generations’

But Swinburne was not alone in his recognition of William Blake’s work. In 1874 writer William Michael Rossetti (1829-1919), brother of Dante Gabriel Rossetti, edited a collection of Blake’s poems. This collection was reviewed by the Nonconformist in November 1874, which outlined a thawing in attitudes towards the eccentric Blake:

William Blake has been a puzzle to two generations, not to speak of his immediate contemporaries, who, for the most part, got rid of the difficulty by writing him down mad. Gradually, the more he has been studied, the more has criticism succeeded in demonstrating the existence in him of a thoroughly sane element, which issued in such gems of pure genius as gives him a claim to rank among memorable Englishmen.

Gradually, bit by bit, Blake was taking his place in the pantheon of celebrated British artists and poets. This slip into the mainstream is evidenced by a talk given in 1878 by the Reverend Mr. Wellwood on ‘The Life and Poetry of William Blake’ at the West Parish Church in Greenock, Renfrewshire.

The lecture, which was reported on by the Greenock Advertiser in December 1878, was ‘well attended.’ The article described how:

The life and character of William Blake, who has often been described as the ‘English eccentric engraver, painter, and poet,’ may not be generally known, but so excellent an epitomised account did Mr Wellwood give that his hearers could not fail to be struck by the lessons taught by the life of one who, through his long life, did not swerve an inch of from his path to obtain recognition.

The lecture also related how in critic John Ruskin’s (1819-1900) opinion, ‘Blake’s works were of the highest rank in imagination and expression; and that Blake was greater than Rembrandt.’

‘A Story of William Blake’

By the 1890s, William Blake’s name needed little introduction. Indeed, in December 1891 his name was printed alongside a characteristic tale of the visionary artist with little or no preamble by the Echo (London), in a short paragraph entitled ‘A Story of William Blake.’ The charming little story runs as follows:

‘Did you ever see a fairy’s funeral, madam?’ said Blake, the English poet-painter, to a lady. ‘Never, Sir,’ was the reply. ‘I have,’ said Blake; ‘but not before last night. I was walking alone in my garden; there was a great stillness among the branches and flowers, and more than common sweetness in the air. I heard a low and pleasant sound, and knew not whence it came. At last I saw a broad leaf of a flower move, and underneath I saw a procession of green and grey grass-hoppers, bearing a body laid out on a rose-leaf, which they buried with songs, and then disappeared.’

However, not all were convinced by the merit of the Blake’s work. In piece published in the London Evening Standard on 26 January 1893, the author outlines how:

As an engraver, original and interpretative, Blake, in due time, reached excellence, and though he became a student at the Royal Academy, his defective or, at the least, very curious sense of colour resulted in his never taking that rank as a painter which he may hold as a designer in black and white. He was never very great, technically, at least with the brush, and there is no doubt that his fertility of invention and his real sympathy with Literature were the greatest and most necessary helps to him in his effort to do work of lasting and serious value.

The article dubs Blake’s painting technique as ‘limited,’ describing how over half his designs are ‘crazy and unintelligible.’ The jury, it seems, was still out on Blake’s legacy.

Memorials and the Establishment of the Blake Society

William Blake’s legacy, however, was greatly in evidence on 12 August 1899, the 72nd anniversary of the artist’s death. This anniversary was commemorated by the Echo (London), which reported how:

To-day is the seventy-second anniversary of the death of William Blake. It is gratifying to find that the poet is not without honour, even in Lambeth, where he lived for many years and did some of his best work. In a recent monograph Dr. Garnett reproached Lambeth with not having put up even a tablet to Blake’s memory.

This neglect of Blake’s memory was soon remedied, as the Echo (London) described:

A South London journalist took this reproach to heart, and the result has been that with the help of a few Lambeth artists, sculptors, and writers ‘a beautiful’ William Blake memorial has been prepared, and will in the course of a week or two be placed in the Central Lambeth Library.

In the following years, Blake’s star continued to rise, as the formerly sceptical Morning Post noted in 1906, describing how ‘the last two or three years have seen an unusually large number of appeals to the public on behalf of William Blake.’

This culminated in the formation of the Blake Society in 1912. Its first meeting, as reported in the Liverpool Echo, would be held on ‘the eighty-fifth anniversary of the death of William Blake,’ with the gathering being ‘held alternately at Lambeth Palace (by permission of the Archbishop of Canterbury), Eastham, Felpham and Chichester.’

‘Splendid Beauty of Invention’

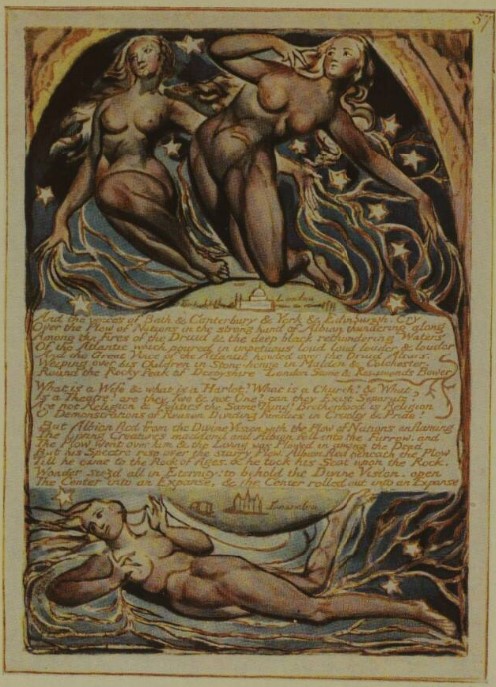

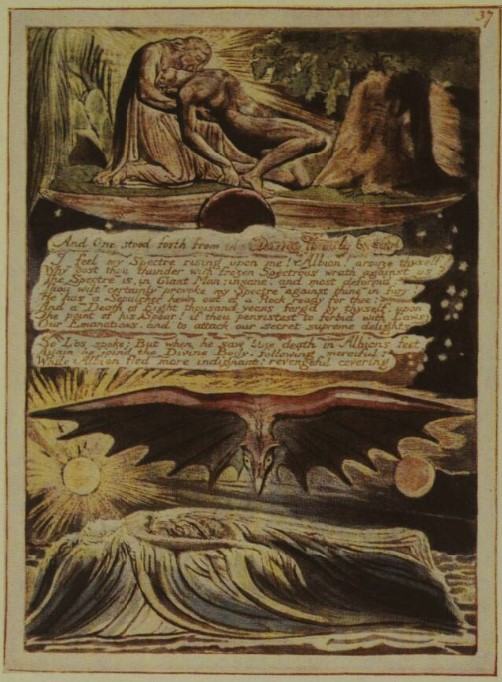

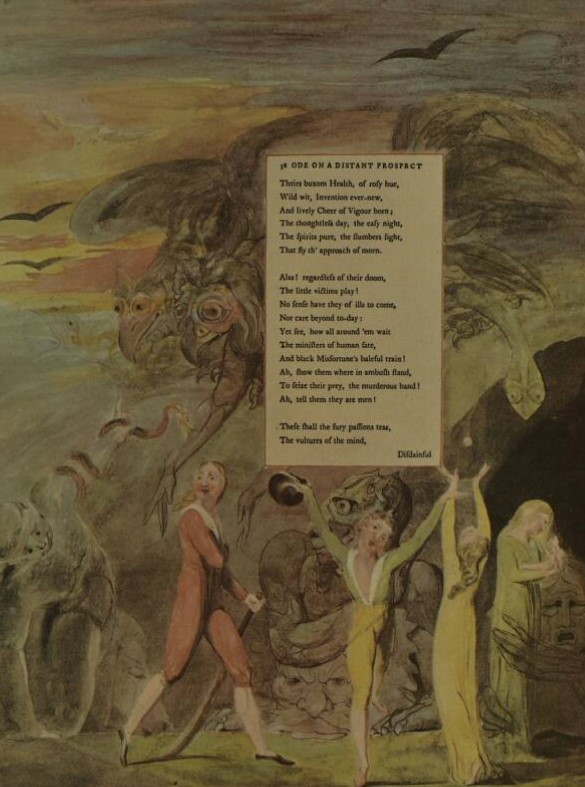

As the hundred year anniversary of William Blake’s death approached, more was written about the poet and the artist. In December 1922 The Scotsman reviewed a book on the drawings and engravings of William Blake, which was authored by Geoffrey Home, with an introduction by poet Laurence Binyon (1869-1943).

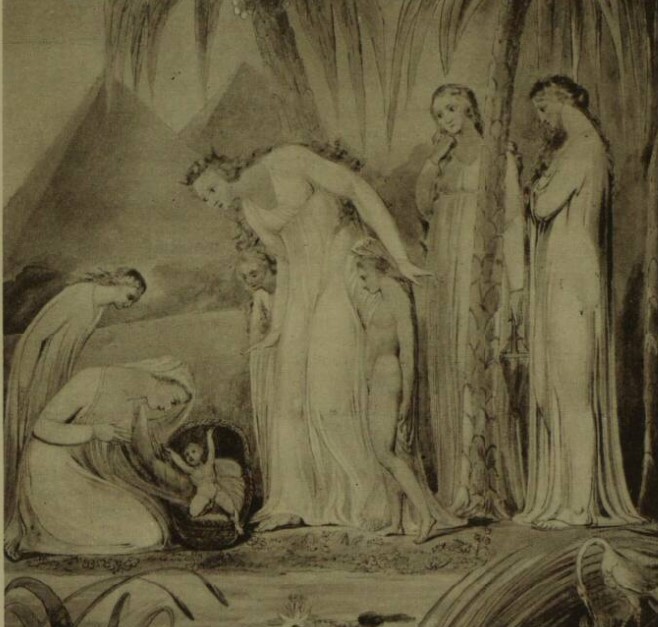

The book featured 104 plates, reproducing Blake’s work, ‘in tones of grey as soft and flowing as the strokes of a lead-pencil.’ The Scotsman’s review of Blake’s artistry is vivid and inspiring, as it describes how his drawings:

…speak of Nativity, not as the old masters did, but with a power no less compelling than theirs, and tell in free phrases of design what cherubs look like to the inward vision of mankind. They pourtray dead gods and fabulous personifications convincingly, translate Shakespeare’s fancies about fairies into a pictorial language that outrivals the spectacular productions of the theatre, and give the episodes of the Bible a visual presentation clearer than many of those that depend on the spoken word…

Indeed, for the author of the The Scotsman’s piece, Blake’s works appeared to ‘fly.’ The piece concludes by observing how:

Veterans and little children alike will find their wondering admiration provoked and guided by the splendid beauty of invention with which they display the morning stars singing together.

Bunhill Fields

The centenary of William Blake’s death was marked by a special ceremony at Bunhill Fields, the London cemetery were the artist was buried, in an unmarked pauper’s grave. The Bedfordshire Times and Independent on 19 August 1927 describes how the Blake Society gathered at Bunhill Fields on 12 August 1927, exactly one hundred years since Blake’s passing.

The Blake Society gathered at Wesley’s Chapel on City Road, opposite Bunhill Fields, to mark the anniversary, after which ‘the congregation…crossed to the burial ground, where a head stone has just been erected to mark Blake’s grave.’ Here, the secretary of the Blake Society, Mr. Thomas Wright, called for a memorial to the poet and artist to be ‘placed in Westminster Abbey, from which Blake drew his early inspiration.’

The British Museum and The Tate Gallery

By the 1950s, the work of William Blake had become of such importance that national institutions like the British Museum sought to acquire it.

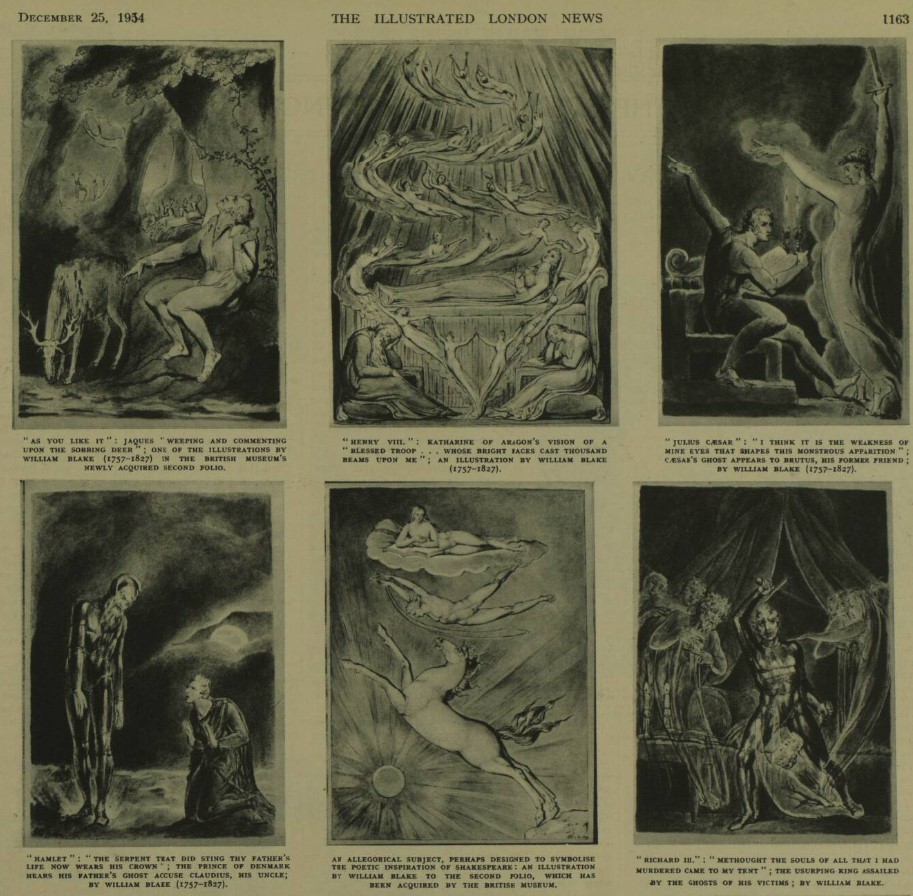

On Christmas Day 1954 the Illustrated London News reported how:

The British Museum recently acquired a copy of the Second Folio of the Works of William Shakespeare, published in 1672, and later enriched with a series of illustrations by William Blake and other artists working in the early nineteenth century, including John Flaxman, George Henry Harlow, William Hamilton and William Mulready.

A few years later, in 1957, the Blake Society were marking the bicentenary of William Blake’s birth by arranging an exhibition of his work, namely ‘Blake’s Bible Illustrations and Facsimiles of his Illustrated Books.’ The Illustrated London News reported how the exhibition could be viewed at the National Book League at Albemarle Street.

In 1970 the same publication dubbed William Blake as a ‘prototype of genius,’ whilst a year later in 1971 the title published reproductions of ‘virtually unknown watercolours’ by the artist, which had just been rediscovered. The watercolours were set to be exhibited at the Tate Gallery.

From obscurity and poverty, the art of William Blake found international recognition and respect. Revived by Victorian critics, and strengthened by devotees in the twentieth century, Blake’s work has been preserved, to live on its dreamy vividness, inspiring wonder in those who view his paintings and drawings. It is left to us to wonder what the man himself would have made of such recognition, as he firmly eschewed the more material things in life.

Find out more about William Blake and other artists in the pages of our newspapers today.