At the British Newspaper Archive we are always delighted to hear how The Archive has been used to inform a range of different research interests. In this very special guest blog, Sidonia Serafini of Georgia College & State University and Barbara McCaskill of the University of Georgia take a look at the work of the Reverend Peter Thomas Stanford, Birmingham’s first Black minister, as reported in the British press, through the newspapers to be found in our collection.

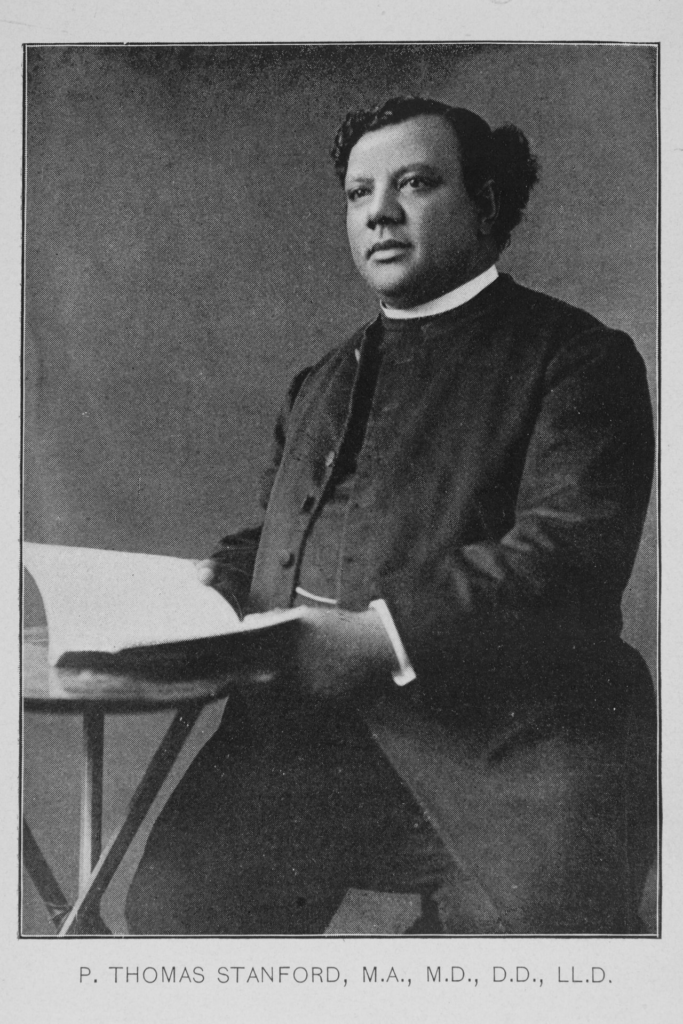

In March 1883, Reverend Peter Thomas Stanford (ca. 1858-1909), a formerly enslaved African American pastor, arrived in Liverpool from Ontario, Canada West (Fig. 1). As this blog explores, his lectures, addresses, and appearances in England between 1883 and 1889 appropriated strategies from African American antislavery activists. He found suitable for his missionary and reform work such antislavery strategies as endorsements of character, intriguing announcements in the periodical press, collaborative appearances with other formerly enslaved persons, public gestures to his African origins and identity, and photographs. They laid the foundation for his appointment as Birmingham, England’s first Black pastor, his anti-racist activism and oratory, and his philanthropy and charitable endeavors in the United States. These strategies also yielded a robust print publication record, including a book-length autobiography, three editions of a textbook, and numerous newspaper articles that appear in our annotated edition of his writings, The Magnificent Reverend Peter Thomas Stanford, Transatlantic Reformer and Race Man (University of Georgia Press, 2020).

Figure 1. Frontispiece photograph, The Tragedy of the Negro in America (1903), from the New York Public Library

Born enslaved near Hampton, Virginia, Stanford made his way as a young adult to Canada’s fugitive slave communities after a precarious life as an orphan in New York and Connecticut (McCaskill and Serafini, 6-7, 251-52).As the chosen emissary for the all-Black, Ontario-based Amherstburg Baptist Association, he was commissioned to make the transatlantic crossing to England with multiple missions to accomplish. His goals would include raising funds to build a new church for Black Baptists in Canada, which would educate his freeborn and formerly enslaved parishioners and neighbors, train a rising generation of Afro-Canadian men as missionaries to Asia and Africa, and launch the transatlantic tours of a group modeled after Fisk University’s renowned Jubilee Singers.

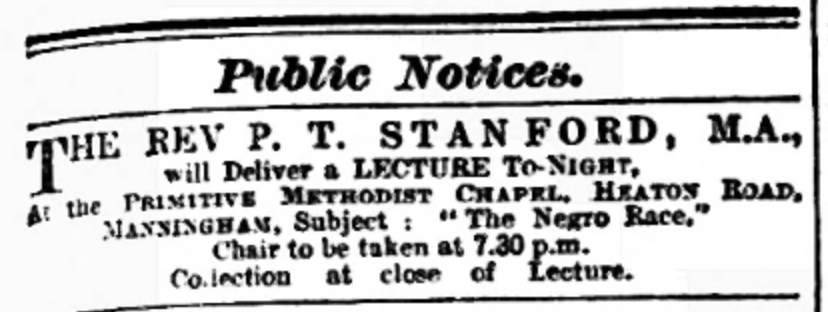

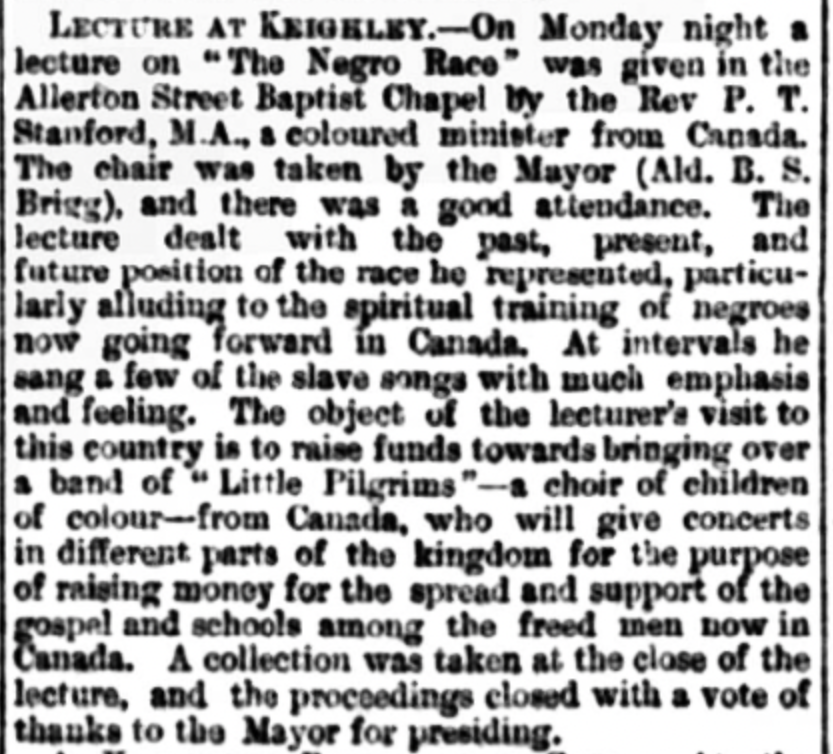

In England and Wales, Stanford worked tirelessly to build a network of alliances, as well as to elevate his reputation as a moral leader and emblem of race progress. As the Bradford Daily Telegraph reported, after only one year he “had visited 102 towns, preached 203 sermons, addressed 82 temperance meetings, delivered 68 lectures, and attended 25 mothers’ meetings” (“The Canadian,” 2). Stanford shaped a public image informed by the peripatetic performances and entrepreneurial sensibilities of African Americans who had journeyed to England in the early to mid-nineteenth century to escape being remanded into bondage and/or to raise support for the abolition of American slavery (see Black Activism). Hannah-Rose Murray has mapped the lecture routes of many of such formerly enslaved African Americans: Frederick Douglass (1818-95), William and Ellen Craft (1824-1900; 1826-91), William Wells Brown (ca. 1814-84), and Henry “Box” Brown (ca. 1815-97). Like these formerly enslaved activists, Stanford enlisted the British press as an ally to advertise and cover his antislavery lectures and appearances across England, to buff his public persona as a lover of freedom and enemy of violence, and, after enslavement had ended, to bolster Black communities in both America and Canada against a rising tide of lynching and political and economic rollback (McCaskill and Serafini, 5-6) (Fig. 2 and Fig. 3).

Figure 2. Bradford Daily Telegraph, July 23, 1883, p. 1.

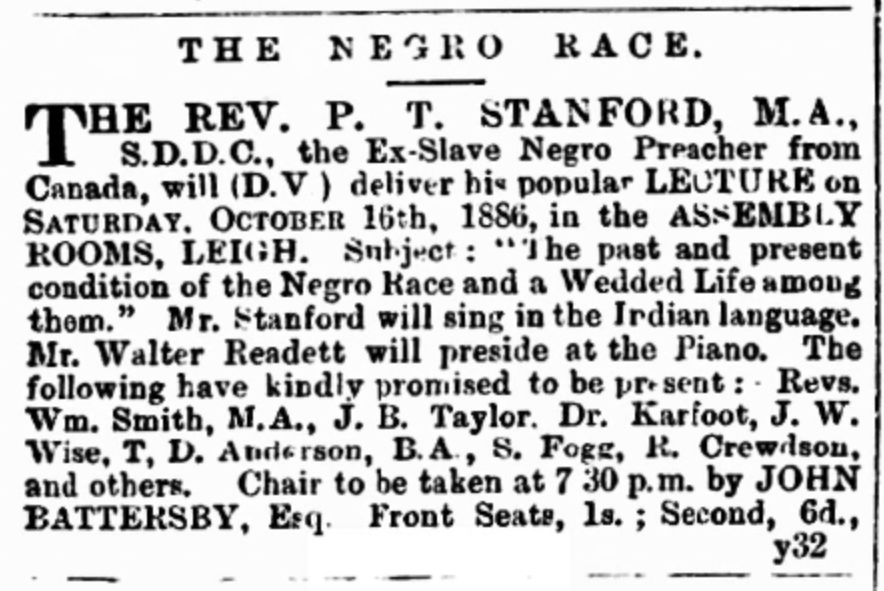

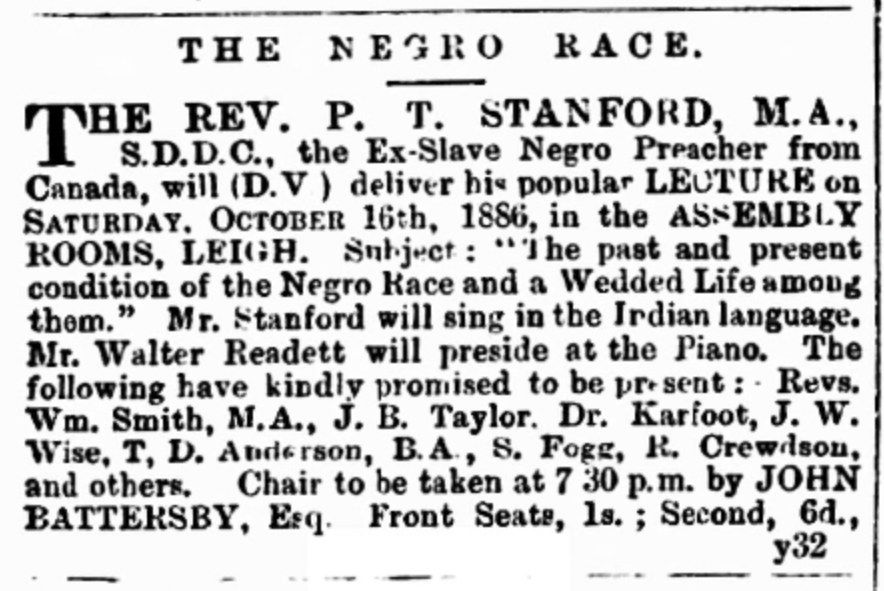

Figure 3. Leigh Chronicle and Weekly District Advertiser, October 15, 1886, p. 1.

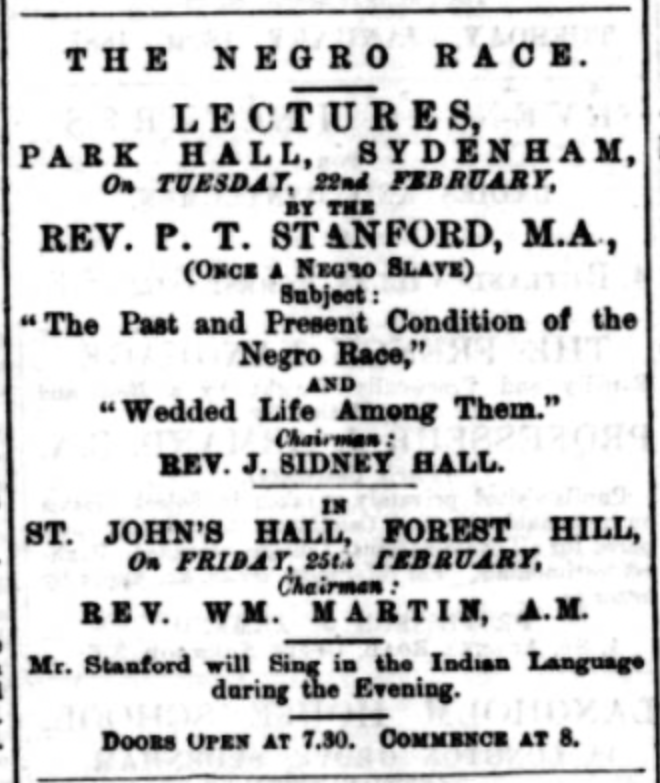

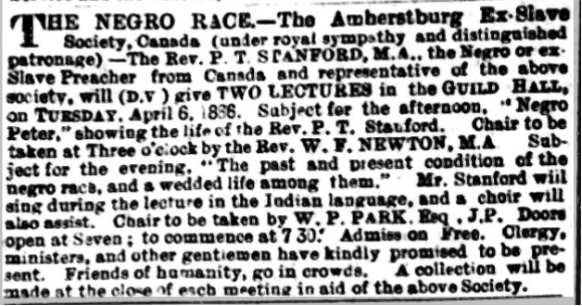

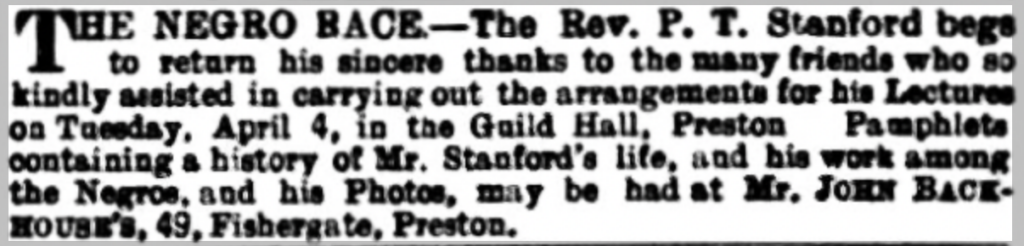

From towns in Greater Manchester (Fig. 4) to the outskirts of London and Birmingham (Fig. 5), Stanford appropriated strategies from abolitionists before him and generated excitement and anticipation by posting notices in local newspapers ahead of his arrival. As the October 15, 1885 post in the Leigh Chronicle and Weekly District Advertiser for Stanford’s lecture “The Negro Race” indicates (Fig. 6), the ministers, physicians, educators, and other townspeople of impeccable character who were in good standing in their communities helped to authenticate his story and sincerity by participating in programs where he also spoke or sermonized. Their visibility at his lectures had a legitimizing effect that was accomplished in slave narratives and other printed accounts of formerly enslaved persons, as James Olney writes in “‘I Was Born’: Slave Narratives, Their Status as Autobiography and as Literature” (50),by the inclusion of letters by white abolitionists, clergy, or educators vouching for the character of Black authors and affirming that they wrote honestly and without exaggeration about the horrible truths of American bondage. Stanford also understood the value of occasionally appearing on the public stage with other formerly enslaved African Americans. The presence of more than one person who had experienced bondage firsthand helped to quell skeptics in the audience, and the sheen of their celebrity magnified his own significance.

Figure 4. Leigh Chronicle and Weekly District Advertiser, October 15, 1886, p. 1.

Figure 5. Sydenham, Forest Hill & Penge Gazette, February 19, 1887, p. 4.

Figure 6. Bradford Weekly Telegraph, June 30, 1883, p. 6.

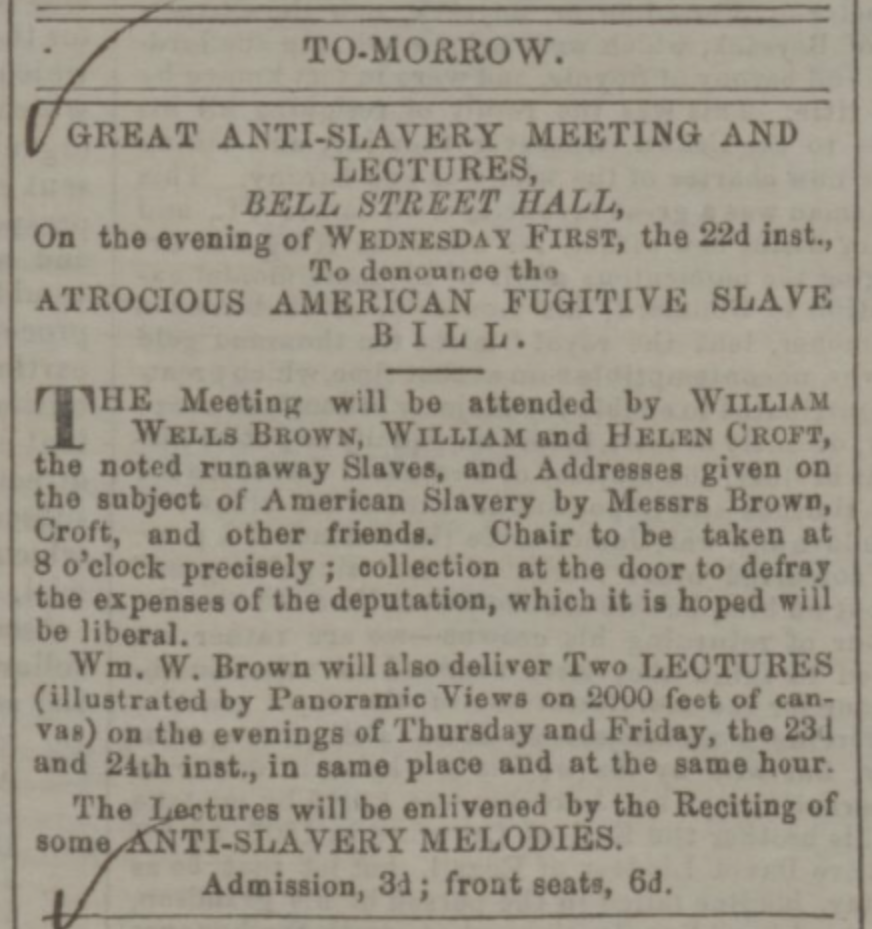

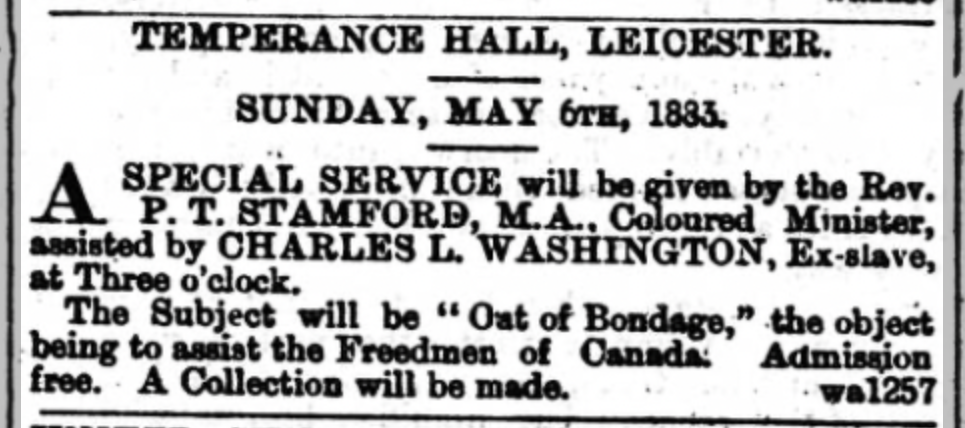

William Wells Brown and William and Ellen Craft were formerly enslaved speakers who appeared together on the British antislavery stage, as advertised in this announcement below of a “Great Anti-Slavery Meeting and Lectures” posted on January 21, 1851 in Scotland’s Dundee, Perth, and Cupar Advertiser (Fig. 7). Similarly, Stanford partnered publicly on at least one occasion with Charles L. Washington (1849-?), the lead tenor of the traveling Wilmington Jubilee Singers of North Carolina, who performed concerts across England throughout the 1870s (Fig. 8). Like Stanford, Washington was born in slavery in Virginia. Like Tulsa, Oklahoma, during the late-nineteenth century decades that preceded the Tulsa Race Massacre of 1921, Washington’s base of Wilmington, North Carolina was home to a booming Black middle-class.Only fifteen years later, the Wilmington courthouse would make history as the site of the ruthless massacre of at least sixty African American men by white supremacists massed there to prevent them from voting—a violent slaughter that would inspire the 1901 novel The Marrow of Tradition by Charles Waddell Chesnutt.

Figure 7. Dundee, Perth, and Cupar Advertiser, January 21, 1851, p. 4.

Figure 8. Leicester Chronicle, May 5, 1883, p. 5.

As advertised above in the Leicester Chronicle (Fig. 8), “Out of Bondage” was the theme of Stanford and Washington’s “special service” held on May 6, 1883 in the Temperance Hall. As the title of the program suggests, both men shared the experience of escaping slavery. The notice also sets them apart. While Washington is identified as an “Ex-slave,” signaling the dismal past from whence he heroically fled, the descriptions attached to Rev. Stanford—“coloured minister” and “M.A.”—point to the present. They do not negate Stanford’s similar ex-slave status. Instead, they move emphasis from the traumatic history of bondage to what has carried Stanford out of it: his religious training and the divinity degree he claims to have earned at Connecticut’s Suffield Institute (McCaskill and Serafini, 6, 93-97, 166-70). The titles have prepared him to make a mark as an activist in this new country and to deliver to the Leicester audience a speech worthy of such credentials by virtue of its persuasive case against slavery and its eloquent advocacy of the fugitive communities back in his Canadian home.

Stanford’s self-inventiveness was similarly abetted by visual spectacle—an impulse not unlike the exhibitions of enslavement and fugitivity staged by Henry “Box” Brown (McCaskill and Serafini, 132-33). Yet Stanford did not exhibit the pain of captivity in the manner that Brown, a fugitive slave, had done throughout the 1850s and 1860s in his moving panorama, Henry Box Brown’s Mirror of Slavery, which included scenes such as whipping posts and slave prisons. Instead, Stanford sang songs that he remembered from his childhood in slavery and songs in Native American languages, as cited in the April 6, 1886 Preston Herald (Fig. 9) and October 15, 1886 Leigh Chronicle and Weekly District (Fig. 3). He had learned what the papers called “the Indian language” during a brief stint with members of the Pamunkey nation when the Grand Old Army arrived and he was separated from other members of the enslaved community as they hastened to leave the plantation and seek refuge in Union encampments (McCaskill and Serafini, 5, 132-34, 145-46). Traveling through Great Britain some twenty years after the Confederacy had surrendered, Stanford perhaps invoked these songs as an expression of the nostalgia for his southern home that he yet possessed in exile, in spite of its history of bondage and lingering racial violence.

Figure 9. Preston Herald, April 3, 1886, p. 1.

Colonel Thomas Wentworth Higginson (1823-1911), a white officer who led the 1st South Carolina Volunteers, the first all-Black regiment of the Civil War, and a confidante of the poet Emily Dickinson (1830-86), had analyzed and published scores of spirituals he had heard Black soldiers sing for an essay in Boston’s Atlantic Monthly (June 1867, 685-94), and again in his memoir Army Life in a Black Regiment (1870). Harriet Ann Jacobs (1813-97) had described the melancholy yet hopeful slave songs in her memoir of slavery in North Carolina, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl (Boston, 1861), published in London as The Deeper Wrong (1862) after the initial American printing. Additionally, Native American language, and other aspects of Native American culture such as songs and clothing, had captured the imagination of English audiences as a result of Buffalo Bill Cody’s Wild West Shows that toured during the 1880s and “cowboy and Indian” stories that were circulated by cheaply printed penny dreadfuls (McCaskill and Serafini, 132). Stanford’s performances of slave songs and Native American language were therefore methods of connecting to his audience through popular culture. While he used his racial and ethnic differences as an attraction, he also invited audiences to contemplate their shared humanity through the mutual experience of the thrilling songs and moving language. He could simultaneously prove his amity for working-class English culture while also capitalizing upon his background experiences in white and Native American communities across the Atlantic.

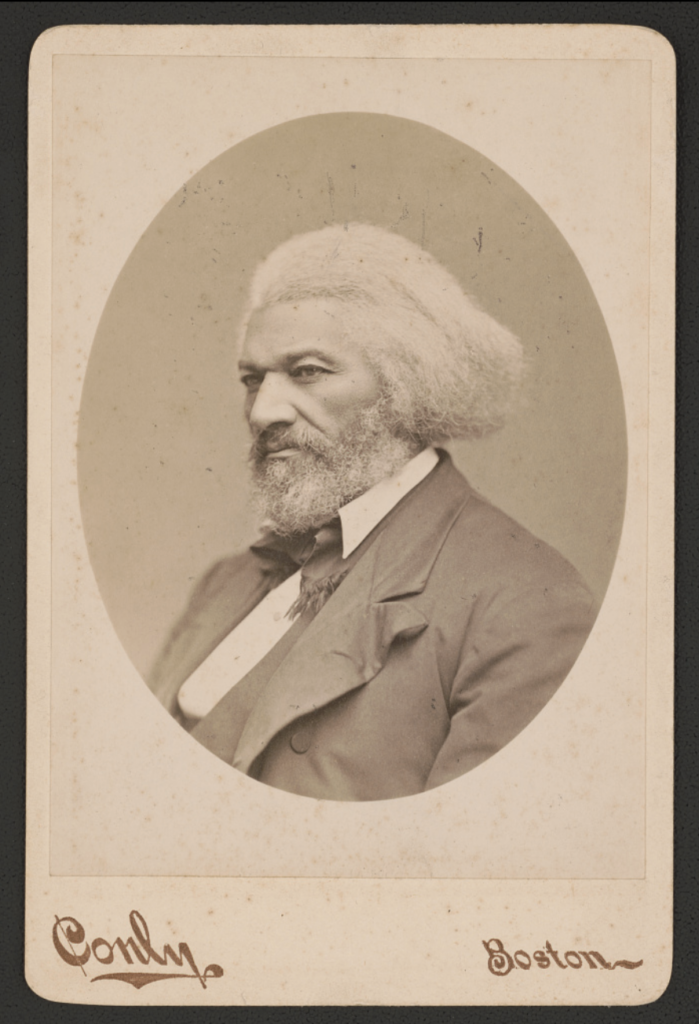

Figure 10. Frederick Douglass / C. F. Conly, Photographer, 465 Washington St., Boston, 1884. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, [reproduction number, LC-DIG-ppmsca-56175]

Ever attentive to how his Black body embodied both the story of African Americans in slavery and their aspirations for advancement and equality in freedom, and like the Black antislavery activists before him, Stanford incorporated photography into his speaking engagements. In this way, he emulated one of his professed heroes and a fellow formerly enslaved American, Frederick Douglass (Fig. 10). The “nineteenth century’s most photographed American,” Douglass had strategically controlled and circulated his photographed image in order to generate specific political and cultural meaning (Stauffer and Bernier, xiii). During the Civil War (1861-65), he had delivered a series of lectures that expressed his understanding of the camera’s implicit ability to assign humanity, dignity, respectability, and introspection to Black bodies. Photographs offered the African American a method to “invent his own subjective consciousness into the objective form” (133), Douglass had stated in his December 3, 1861 “Lecture on Pictures,” which the papers referred to as “Pictures and Progress” (Stauffer and Bernier, 133, 126).

Fig. 11. Preston Herald, April 10, 1886, p. 12.

As this April 10, 1886 Preston Herald notice demonstrates (Fig. 11), Stanford linked photographs of himself to his “work among the Negros” and missionary zeal. In addition to advertising the sale of his image, he also delivered addresses that centered photography. In March 1887, he presented a lecture entitled “The Influence of Pictures” at Park Hall, Forest Hill, London (“Wells Road,” 5). In November 1889, he addressed the congregation of the United Methodist Free Church of Bromsgrove with a sermon titled “Have You Had Your Picture Taken?” (“United,” 8). Even after Stanford had established himself as a religious leader in Birmingham, he imbued his sermons with threads from his previous lectures. In sacred spaces, he continued to deliver his well-known lecture, “The Past and Present Condition of the Coloured People of America,” illustrated with images projected from a magic lantern (“Union,” 1). As he did with the slave songs and “Indian language,” the coupling of his photograph with the novel technology of the magic lantern to tell his story that begins in slavery looks to both past and present.

On the stage and in the pulpit, Stanford embodied and amplified a narrative arc of post-Emancipation African American achievement. Exemplifying this goal was his lecture “The Past and Present Condition of the Negro Race,” also titled “The Negro Race,” which the Leigh Chronicle and Weekly District Advertiser acknowledged as his most well-known address (“The Negro Lectures,” 5). Stanford’s remarks shared with eager listeners the history of slavery, his story of overcoming poverty and isolation through literacy and initiative, and his vision of a future in which people of African descent had equal access to education and civil rights. According to one newspaper writer who attended this speech at Todmorden, Yorkshire’s Roomfield Baptist Chapel, Stanford celebrated a future in which African Americans were given “schoolhouses and books instead of whips and watchmen” (“Lecture,” 4).

These advertisements, notices, and reflections about Reverend Peter Thomas Stanford’s public appearances during the 1880s demonstrate how figures and stories from American slavery resonated among popular audiences after Emancipation and near the turn into the twentieth century. The moment when they circulated—the post-bellum, pre-Harlem Renaissance decades—was a mixed bag for the prospects of African Americans like Stanford. As Barbara McCaskill and Caroline Gebhard have written, these decades were characterized by an outpouring of optimism, creativity, and pride among formerly enslaved and born-free African Americans that has often been obscured by perceptions of this time as a low point in the culture (Post-Bellum, Pre-Harlem, 1-14). Yet, physical and psychological assaults against Black families and communities remained, and in many places increased, and economic and educational inequality, racial stereotyping, and other lingering social challenges persisted. The good Reverend’s travels through English towns and cities as reported in the newspapers necessarily reached back to antislavery strategies of performance and speech, not only for his own self-advancement and to connect to British audiences, but also to attach themes of achievement, possibility, and success to the ongoing, unfinished story of Africans in America.

Works Cited

Black Activism: A Transatlantic Legacy. Directed by Barbara McCaskill, Sidonia Serafini, and Kelly Dugan. blackatlantic.uga.edu.

“The Canadian Negro Mission.” Bradford Daily Telegraph, April 29, 1884, p. 2.

Douglass, Frederick. “Lecture on Pictures.” 1861. In Picturing Frederick Douglass: An Illustrated Biography of the Nineteenth Century’s Most Photographed American, edited by John Stauffer, Zoe Trodd, and Celeste-Marie Bernier. Liveright, 2015, pp. 126-41.

Higginson, Thomas Wentworth. Army Life in a Black Regiment. Fields, Osgood, and Co., 1870.

—. “Negro Spirituals.” The Atlantic Monthly,no. 19, June 1867, pp. 685-94.

Jacobs, Harriet Ann. The Deeper Wrong; Or, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl. Written by Herself. Edited by L. Maria Child. W. Tweedie, 1862.

—. Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl. Written by Herself. Edited by L. Maria Child. Published for the Author, 1861.

“Lecture on the Past, Present, and Future of the Negro.” Todmorden Advertiser and Hebden Bridge Newsletter, March 9, 1883, p. 4.

McCaskill, Barbara, and Caroline Gebhard. Post-Bellum, Pre-Harlem: African American Literature and Culture, 1877-1919. New York University Press, 2009.

—, and Sidonia Serafini, with Rev. Paul Walker. The Magnificent Reverend Peter Thomas Stanford, Transatlantic Reformer and Race Man. University of Georgia Press, 2020.

Murray, Hannah-Rose. Advocates of Freedom: African American Transatlantic Abolitionism in the British Isles. Cambridge University Press, 2020.

“The Negro Lectures.” Leigh Chronicle and Weekly District Advertiser, October 22, 1886, p. 5.

Olney, James. “‘I Was Born’: Slave Narratives, Their Status as Autobiography and as Literature.” Callaloo, no. 20, Winter 1984, pp. 46-73.

Stauffer, John, Zoe Trodd, and Celeste-Marie Bernier. Picturing Frederick Douglass: An Illustrated Biography of the Nineteenth Century’s Most Photographed American. Liveright, 2015.

“Union Baptist Church.” Birmingham Mail, March 14, 1891, p. 1.

“United Methodist Free Church.” Bromsgrove & Droitwich Messenger, November 30, 1889, p. 8.

“Wells Road Emigrants.” Sydenham, Forest Hill & Penge Gazette, March 19, 1887, p. 5.