At The Archive we are delighted to welcome guest blogs from our users, which highlight a wealth of different research interests. This month, we are excited to feature a blog on researching queer history by Staffordshire researcher Rebecca Morris-Quinn.

My name is Rebecca, I am a queer woman living in Stoke-on-Trent, Staffordshire. I’ve been interested in genealogy and history for many years, since I found out that I share a birthday with a great-great aunt, Olive (albeit over 100 years ago). Olive loved art, like me; was a trained teacher, like me; and suffered from very frizzy hair; like me. I felt an affinity to her and wanted to know more about her.

I feel that the need of knowing where we come from and that we are not alone is universal. This is especially true of the queer community, as a group of individuals on the fringes of society, it can be very difficult to find evidence of queer ancestors.

Olive was on my maternal grandmother’s side. She had seven sisters, all born in the late 1800s. They never married and lived together in a big house in Harrow, London. They were all accepted by the family and my grandma recalls many holidays spent with them.

Looking at the data recorded from the 2021 census, of 92. 5% of people who answered the question on sexual orientation, 3.2% identified on the queer spectrum. This is around 1.5 million people. Bigger than the 2023 population of Birmingham.

So what is the possibility of at least one of Olive’s seven sisters (or herself) being queer?

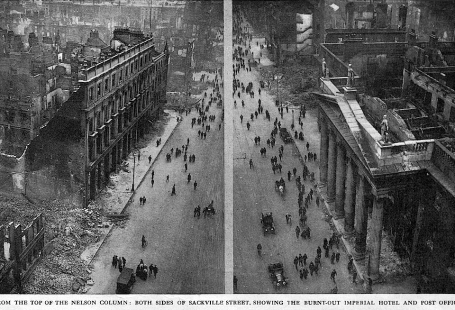

Since moving to Stoke from London I have realised how London-centric history and thus queer history is in the UK. I have begun to combat this by researching possible queer individuals from the West Midlands and beyond. There are not many tips out there for researching queer ancestors and in this article I hope to highlight some of the common themes I have seen in my research.

Introduction

I will be using the word ‘queer’ as an umbrella term in this article. It is difficult to attribute an individual to a certain sexuality, especially when words for these feelings had not yet been created. I see ‘queer’ as more of a spectrum than the clear definitions of Gay, Straight, Bisexual etc. This makes the term feel more inclusive of people who may not fit in to the ‘prescribed boxes’.

Historically, ‘queer’ has been used as a slur against LGBT+ people, however since the 1980s, LGBT+ communities have been working to reclaim it.

Queer Ancestors

The most common way that you will find queer family members is if they have been reported in legal documents. This tends to mainly be men, for crimes such as sodomy, buggery or gross indecency.

Sodomy was a capital offence until 1861 when it was commuted to ten years penal servitude. In 1885, the Criminal Law Amendment Act made any male homosexual act illegal, meaning it was a lot easier to convict. Unnatural acts or offences could be anything from men writing to each other too affectionately, loitering ‘with intent’ or wearing female attire.

Legal documents can only take us so far in understanding the views of the time that our ancestors lived in. Newspaper articles can add colour to an event which is sparsely mentioned in legal documents or passing down by word of mouth from long ago.

Presentation

Queer individuals present themselves in many forms. You have more flamboyant individuals, such as drag kings and queens, dressed up to the nines in wigs, outrageous make-up, flouncy dresses or button-up suits. Then there are people who just want to wear trousers or a dress without the fear of retribution.

Up until the 1930s, the British public were inundated with salacious gossip in newspapers and magazines about men and women caught in the ‘wrong’ clothes for their gender. The papers argued that it was immoral, unnatural and offensive. Queer men tended to come out (pun not intended) worse from this public outrage. In the UK, lesbianism tended not to be spoken about; many people thought that women did not have a sexual agency and it was decided by the UK government that female homosexuality would not have the same illegality as male homosexual as they didn’t want to give women any ideas!

I have found it is more difficult to find queer women in history than it is queer men. Buggery, sodomy, unnatural offences or acts were often prosecuted in courts of law. Although it was widely known in the queer community that women could have sex with other women, the police were stumped as to how to prosecute this.

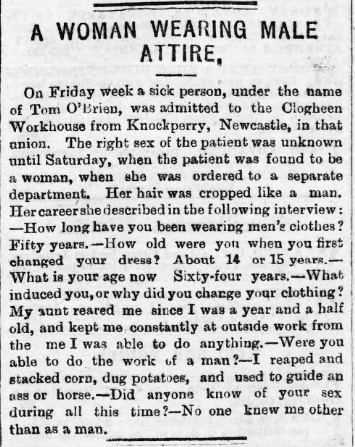

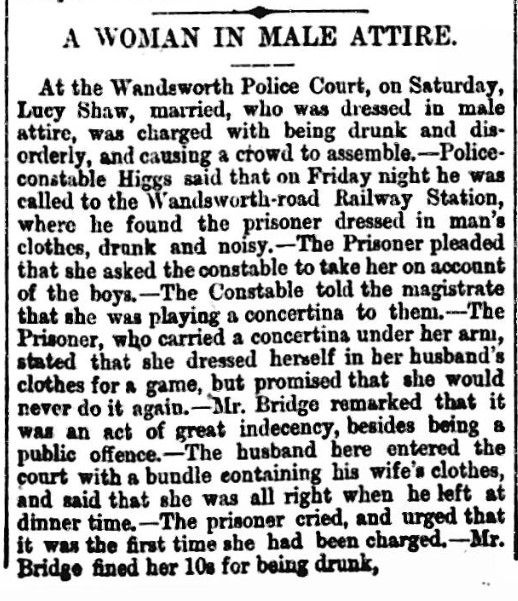

The main offences that women were charged with tend to be ‘wearing male attire’, however, these were often not prosecuted in courts or assizes, it is mainly through newspaper articles that these ‘offences’ are found.

From the late 1800s there was an increase in women being stopped by police for wearing their husbands clothes. This was described by one magistrate, in December 1876, as:

an act of great indecency [and] a public offence

Mr. Bridge, magistrate, 26 December 1876, Lucy Shaw, Wandsworth

Read more about Lucy Shaw and other women caught in ‘male attire’ here.

Supportive Families

Many people consider being supportive and accepting of queer individuals a relatively new invention. The information I found when researching suggest differently.

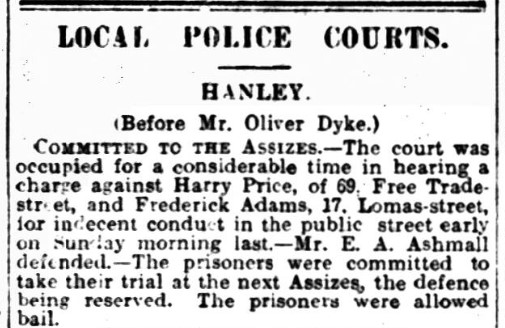

Frederick Adams was born in 1879 in Hanley, Stoke-on-Trent. He and his eight siblings grew up in Shelton where they followed their father into the pottery industry that thrived in Stoke-on-Trent in the Victorian era. Frederick worked for Ridgeways Pottery, situated on the Caldon Canal in Shelton. In May of 1914, Frederick Adams and Harry Price were charged with ‘unlawfully committing an act of gross indecency with each other.’

The pair were committed to the Staffordshire Assizes, where arresting PC Harrison reported that they “had had [a] drink, but knew what they were doing”. The jury returned the verdict of ‘not guilty’ and the men were discharged.

After the trial, Frederick continues to live with his mother and his sister and her family. In 1929, his suicide is reported in the Staffordshire Sentinel. There is no mention of his sexuality in the newspaper reports, it focuses on Frederick’s family mourning him and his struggle with mental health and unemployment.

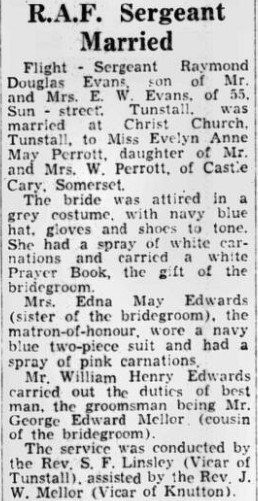

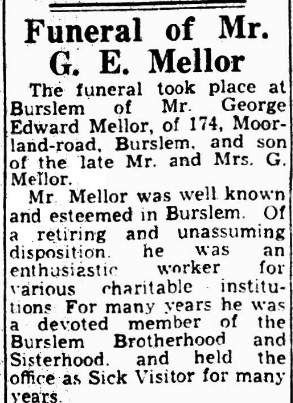

Support and continued inclusion of relatives is also seen in George Edward Mellor’s family. In 1924, he is charged with “committing, in company together, a serious offence in South Street, Hanley on the 7th of June”. Yet, years later in 1941, George is requested to be best man at his cousins wedding.

On his death, in 1944, George is mourned in newspapers of the time. He is described as a well-known figure in the town (Burslem), and being of a “retiring and un-assuming disposition,” he was known as an enthusiastic worker for various charities in the town.

Lavender Marriages

Another common thread I have found is that the individuals convicted of these offences tend not to marry, marry late in life or very suddenly, after the crime is committed.

Marrying later in life is something that can happen to people of all sexualities; however in the 1800s, most people had married by their early 20s and were expecting grandchildren by their 40s.

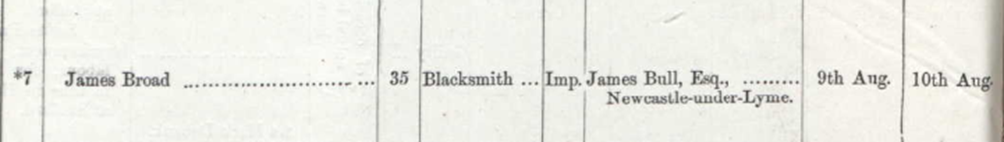

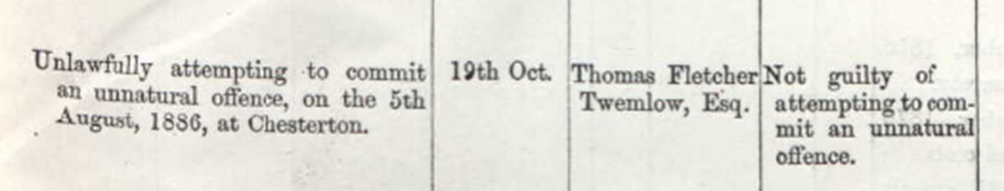

In August 1886, a warrant is put out for James Broad, a 35 year old blacksmith from Talke Pitts, Staffordshire.

Three years after the trial, James marries. Did he feel he needed to prove his sexuality by getting married? Not getting married prior to the trial could also point to him being queer. Many queer men of the time did follow societal conventions by marrying early and starting a family. Possibly using this as a kind of alibi against queer speculation. Did James just have no interest in women prior to his trial and then only as a smokescreen to his sexuality?

Hannah is also older when she marries James, could it be that it was a marriage of convenience? Hannah previously lived with her grandparents and then her uncle. Perhaps by marrying James, a man who might have had little interest in her, she was offered more freedom.

Another argument for James being queer is that he moves away from Talke after the trial. From looking at the censuses we can see that the family stayed in the same house for at least 20 years. Was it that the family knew the truth and turned him out for being queer? Or was it to escape rumours from the locals ruining the family business? We don’t know if there was any truth to the claim of James partaking in ‘unnatural acts’. Blackmail using claims such as this have been around for a millennia, and he wouldn’t be the first, or last, person to be witch-hunted for false claims.

Conclusion

Queer people have existed since the beginning of time. Records of queer individuals come from ancient Greece for example Sappho, a poet from Lesbos, who wrote about intense female relationships; Achilles and his great lover Patroklos fighting in the Trojan war; pharaoh Hatshepsut challenged gender norms in 1500 BC Egypt, and more recently Alan Turing solving the Enigma Code in 1940s Britain.

We have to be careful when attributing queerness to people in the past. Queerness and how we present has changed considerably throughout history; however, who and how we love has not.