In the early 1900s British authorities took a new approach to education: open air schools. Inspired by methods of teaching in Germany, these open air schools were intended to provide disadvantaged city children with fresh air, alleviating their poor health and preventing the spread of tuberculosis.

In this special blog, using newspapers taken from our Archive, we will investigate the open air schools of the 1900s, from their early inception, to how they continued to play a role in education even after the Second World War.

‘Nature Cure for Children’

One of the earliest mentions of open air schools we could find in The Archive was from May 1906. This piece, which was published by Blackburn’s Northern Daily Telegraph, was entitled ‘An Open Air-School.’ It detailed how the ‘approach of fine weather’ had ‘induced the London Education Authority to embark upon an experiment in the shape of an open-air school for certain children,’ who were pupils at a school for the deaf.

The piece reported how the experiment was following in the footsteps ‘of the Manchester country school for poorer children, and similar to the forest schools in Germany.’ A few years later, the Woolwich Gazette on 16 October 1908 explained for its readers the rationale behind these open air schools:

The idea first came from Germany, and they had been trying to improve on it there. Instead of having the closed school rooms, many believed the open air would be much better for the children, and they all hoped that when the children left that open-air school and went to their own homes, the parents would try as far as they could to carry out the object of the school. Many were too fond of shutting up their windows all day and all night. If they could only see the number of microbes which gathered during the 24 hours when rooms were closed it would startle a good many of them. They would then be glad to get out of the house.

Back to 1906, and the pioneering open air school experiment was to be conducted near Maldon, Essex. A few months later, the Birmingham Daily Gazette on 23 June 1906 described this ‘nature cure for children:’

A trip down the wide estuary of the Blackwater from the quaint old Essex town of Maldon will land you on the shingly shore of Osea Island. And if you remark on the little groups of boys and girls, all wearing red tam-o’-shanters, clustered round blackboards and gesticulating teachers on the beach, you will be told that it is the Homerton Residential School for the Deaf combining holiday-making with open-air lessons.

74 children, along with their headteacher, the matron, five teachers, three attendants, the cook and the housemaid, had relocated from Homerton, in East London, to the seaside, in search of the health benefits of the sea air. The experiment seemed to be a success, the Birmingham Daily Gazette observing how:

One need only spend an hour or two on Osea Island to realise the great physical advantages the children must enjoy…There is always a fresh breeze at Osea — a breeze laden with health-giving ozone — and this, with the summer sun, tans the pale cheek even in the necessarily short visit between tides.

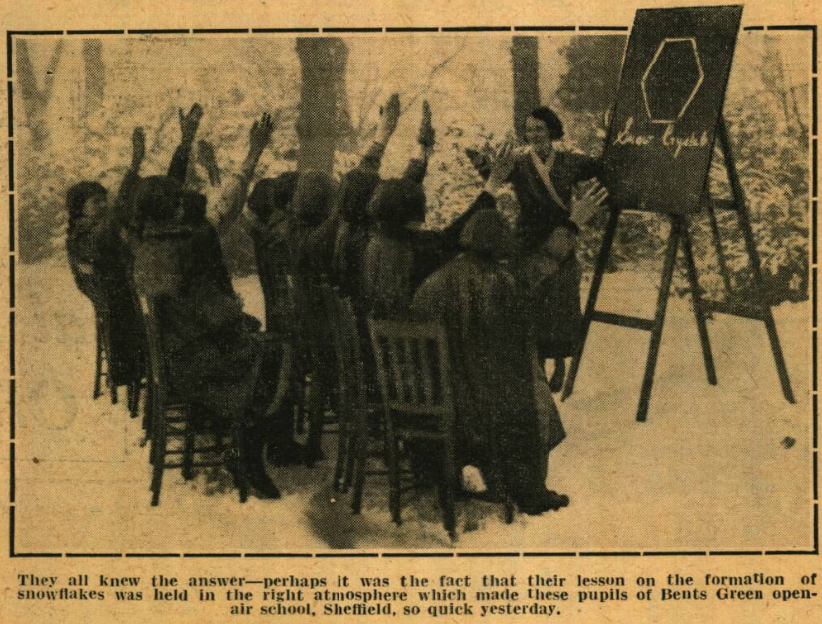

Experiments and Exhibits

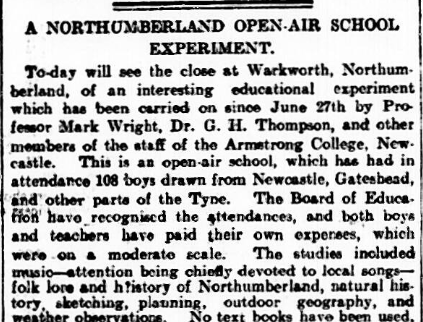

Soon, the open air school experiment began to spread around the country. In July 1908 the Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer described an ‘Open-Air School Experiment,’ which saw ‘108 boys drawn from Newcastle, Gateshead, and other parts of the Tyne’ travel to Warkworth in Northumberland. Staying in tents, the boys studied ‘music —attention being chiefly devoted to local songs – folk lore of Northumberland, natural history, sketching, planning, outdoor geography, and weather observations.’

Another interesting method of education was applied at the Warkworth camp: no text books were in use, the Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer explaining how the pupils were being taught ‘to use their own initiative and independent observation.’ The experiment was a success, with Scouts founder Robert Baden-Powell even approving of the scheme.

By the autumn of 1908, a model of an open air school was being exhibited at the Franco-British Exhibition. The Westminster Gazette described how ‘very few…are aware that such an institution is an educational and ameliorative factor in actual being.’ Indeed, by 1908 London had three open air schools, which were located at Shooter’s Hill, Kentish Town, and Horniman Park.

In October 1908 the Woolwich Gazette published a detailed look at the open air school at Horniman Park, which was situated at Birley House. In the garden of Birley House there was ‘a long structure or schoolroom, one side open to the air,’ where the children had their lessons. The school was able to benefit from the neighbouring Horniman Museum, with its large collection of natural history exhibits and other curiosities.

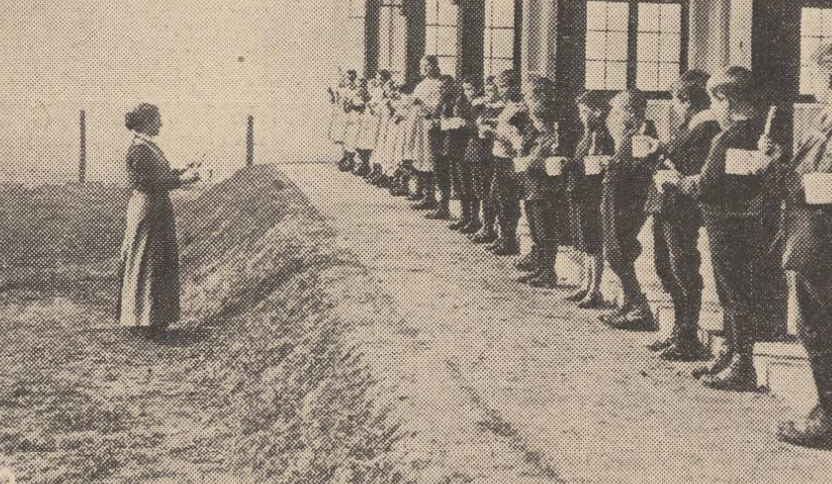

The Woolwich Gazette described the daily routine at the open air school:

The children had been there for the past five months, coming at nine in the morning and remaining until six in the evening, and had remained in the open-air the whole time. For two hours in the middle of the day… [headmistress] Miss Beer allowed the majority of them to go to sleep.

Soon, children across Britain were seeing the beneficial effects of open air schools.

‘Unrecognisable’ Benefits

Such were the benefits of open air schools, that philanthropists like Mr. and Mrs. Barrow Cadbury were keen to support the establishment of more outdoor institutions. The Morning Leader on 25 June 1910 reported how:

A letter was read at the meeting yesterday of the Birmingham Education Committee from Mr. and Mrs. Barrow Cadbury offering a field of five acres for use as an open air school and also to provide the simple building and furniture required for its equipment.

The school would be intended ‘for the use of debilitated and sick children,’ in the hope of achieving the same benefits as seen at other open air schools. On 1 February 1911 national newspaper the Daily Mirror contained this positive report on the open air schools run by the London County Council (L.C.C.):

The open-air schools and playground classes organised by the L.C.C. have met with remarkable success. According to one medical report, children from Bethnal Green, formerly ill-nourished, ill-clad, pallid and inert, could scarcely be recognised by a school doctor three weeks after his inspection of the class, so great was their improvement.

The piece continued:

The difference was partly one of complexion, but also in great degree of demeanour, which was unmistakably more alert and spirited. There was no doubt that the vigour of the children, both bodily and mentally, was directly improved by the open-air life. On inclement days the class was held under cover, but not indoors. Particular attention was paid at all times to physical education, including breathing exercises and the correction of faulty attitudes.

The Movement Spreads

It was little wonder, then, that the open air school movement was spreading. The Derby Daily Telegraph on 16 August 1913 described how:

The West Riding County Council are erecting at Highfields, a mining village near Doncaster, the first of a new type of school building. This is an ‘open-air’ school. This type, which has been designed by the County Council’s education architect, Mr. John Stuart, will supersede the ‘quadrangle’ type of school building now being erected in the Riding. It retains the quadrangle, but the classrooms are planned that two sides can be thrown open and the children work practically in the open air.

Meanwhile in Worcestershire, plans for a new open air school were also being considered. The Bromsgrove & Droitwich Messenger on 22 November 1913 detailed how:

The Sanitary Sub-Committee reported that, according to the School Medical Officer, there were at least 1000 children in the county who would derive great benefit by being educated for varying periods in an open air residential school. The County Council and Insurance Committee having now decided to treat both the insured and uninsured cases of tuberculosis made the present an opportune time to urge again the necessity of the provision of open air schools as part of the general scheme in dealing with tuberculosis in the county.

Plans in Leicester were also in motion, the Leicester Daily Post on 27 October 1919 writing how:

No one will quibble over the expenditure of £6,000 for an open-air school on the Western Park, if, as is expected, it results in improved health for the 300 delicate children for whom it will cater. The scheme comes before the Education Committee at its meeting this evening, when further details will doubtless be submitted.

By 1922 that charitable pair of Mr. and Mrs. Barrow Cadbury had given their country house and estate at Blackwell, near Bromsgrove, to the City of Birmingham ‘for use as an open-air residential school,’ as reported the Folkestone, Hythe, Sandgate & Cheriton Herald. Named the Cropwood Open Air School, it could accommodate 52 children from the ages of 9 through to 13. The newspaper described how:

They will be children who in the city are too tired for lessons, children who are under developed or suffering from anaemia, debility or other troubles, but who may be transformed into thoroughly healthy boys and girls.

The ‘Best Hygiene Conditions’

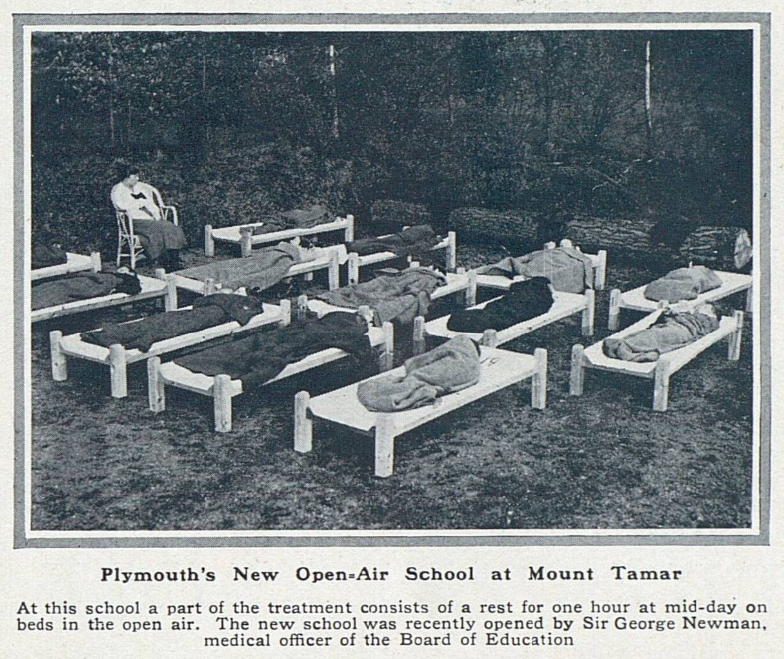

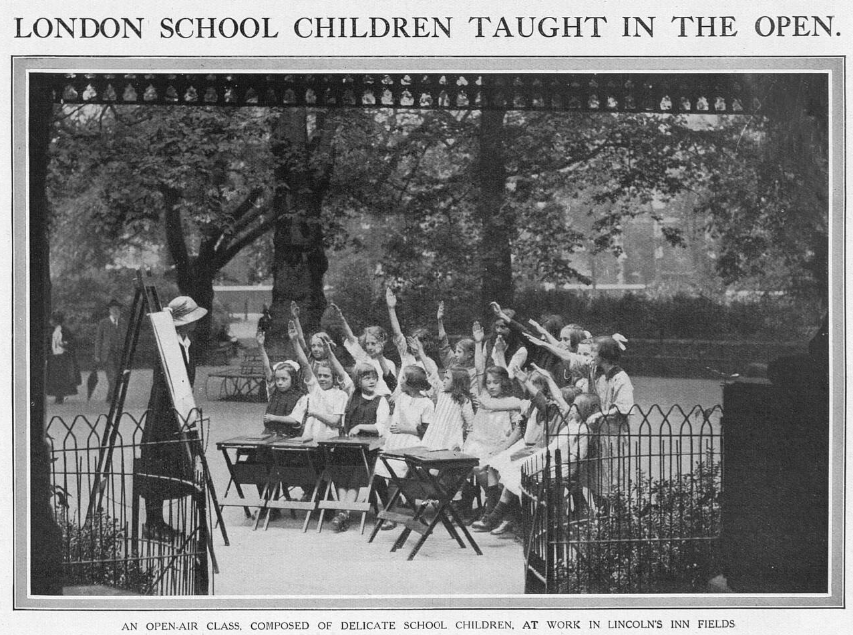

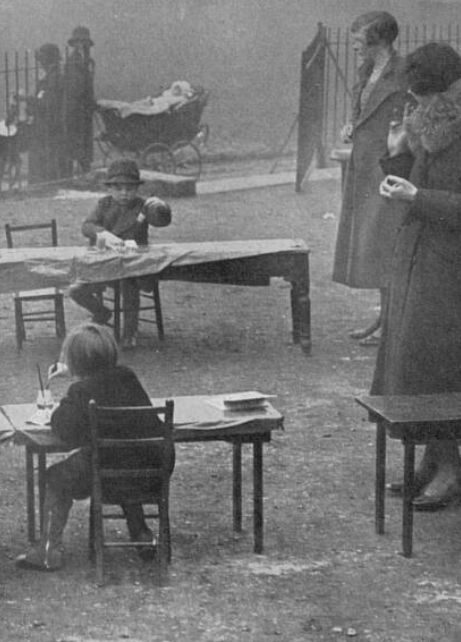

Benefits of open air schools continued to be seen into the 1920s. Picture rich publication The Sphere published photographs of an ‘open-air class, composed of delicate school children, at work in Lincoln’s Inn Fields’ on 13 September 1924, outlining how:

In order to benefit the poor children who are not very robust physically, an open-air class has been started in Lincoln’s Inn Fields, a few seconds from the swirling traffic of Holborn. The children are all drawn from the Holborn area, and in case of inclement weather an adequate shelter has been provided for them.

The Marylebone Mercury on 18 July 1925 outlined the continuing need for such open air schools. According to the Medical Officer for Health to the Willesden District Council, Dr. Buchan, if unwell children were ‘compelled to attend an ordinary school and more particularly one where ventilation and lighting are deficient and where the hygienic conditions are subnormal, their condition cannot improve, and in every probability it will be aggravated.’ He stated how:

What they require is teaching under the best hygienic conditions, and this can only be accomplished in an open air school, where the child will be fed regularly and properly, given an adequate amount of rest and treated with sunshine baths and exercises in the open air. Physically defective children – suffering from anaemia and debility and other diseases in an incipient stage can only be satisfactorily dealt with when an open air school is established at Willesden.

Different Types of Open Air Schools

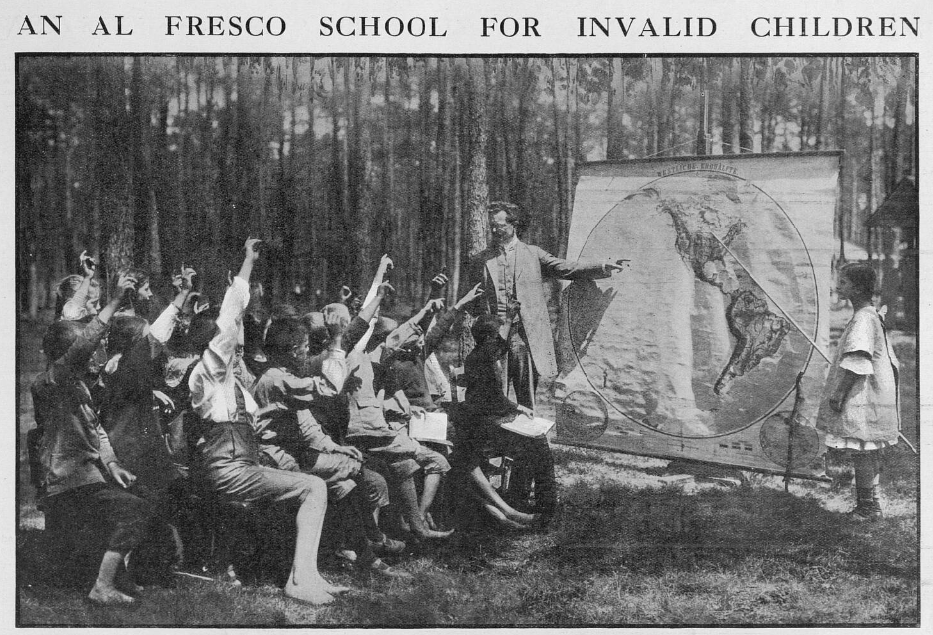

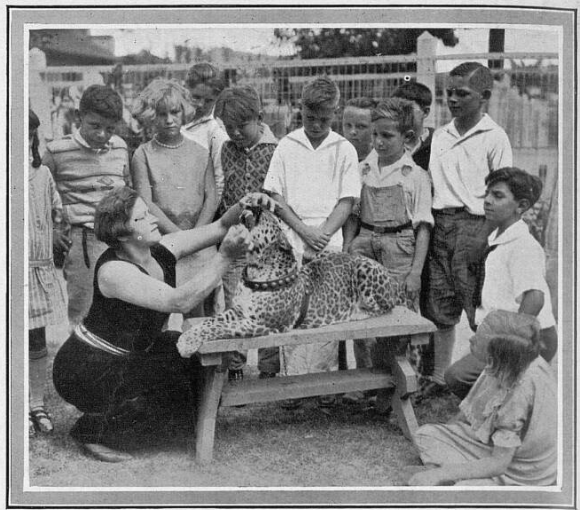

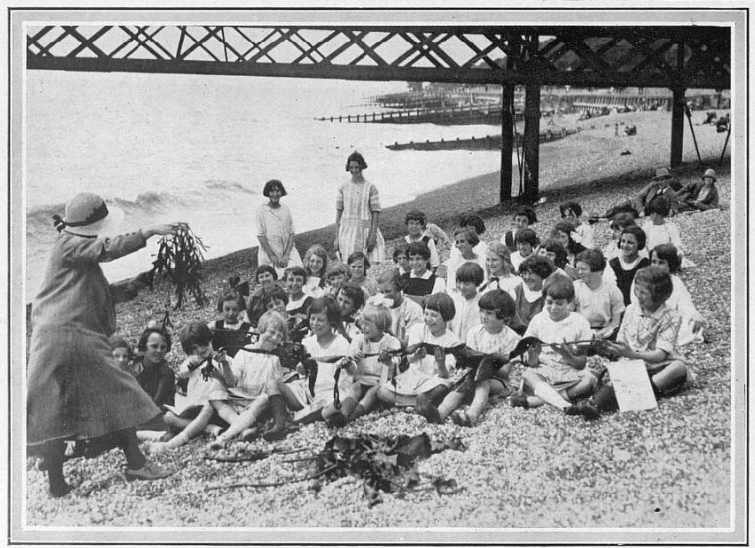

Over time, the idea of open air schooling developed. The notion led to a more hands-on approach to education, with trips out to places of interest, taking lessons beyond the classroom. The Sphere dubbed this ‘new experiment’ as ‘schooling without books,’ describing how:

There is a strongly developed tendency in modern education to take the child to some special centre and there instruct him with the desired objects around him. The most highly developed example of this method is shown in the picture from Los Angeles, where Miss Olga Celeste, a well-known animal trainer, conducts an outdoor natural history lesson among her trained leopards.

Closer to home, The Sphere outlined how:

In this country the same policy is being carried out, children being taken to museums, picture galleries, the Houses of Parliament, and other places, and lessons being given on the spot where that is possible. Holiday lessons are also given, the children being taken to the seaside, either at the parents’ expense or by charitable aid, or at the expense of the school.

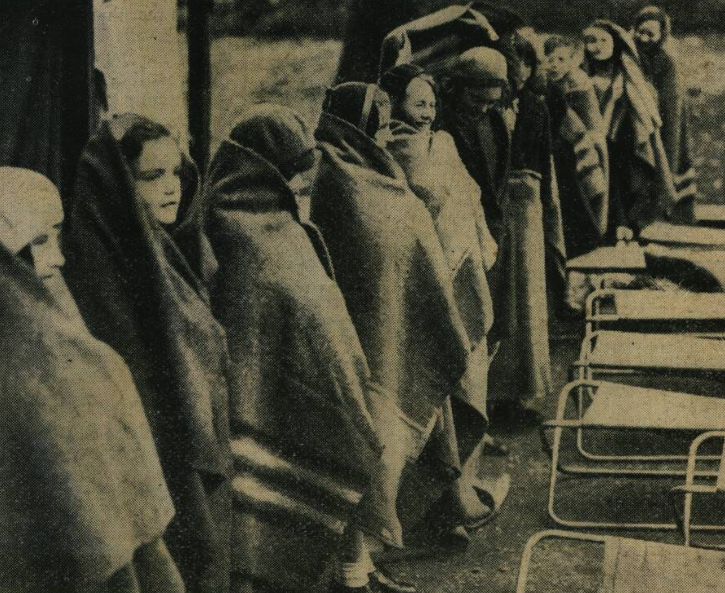

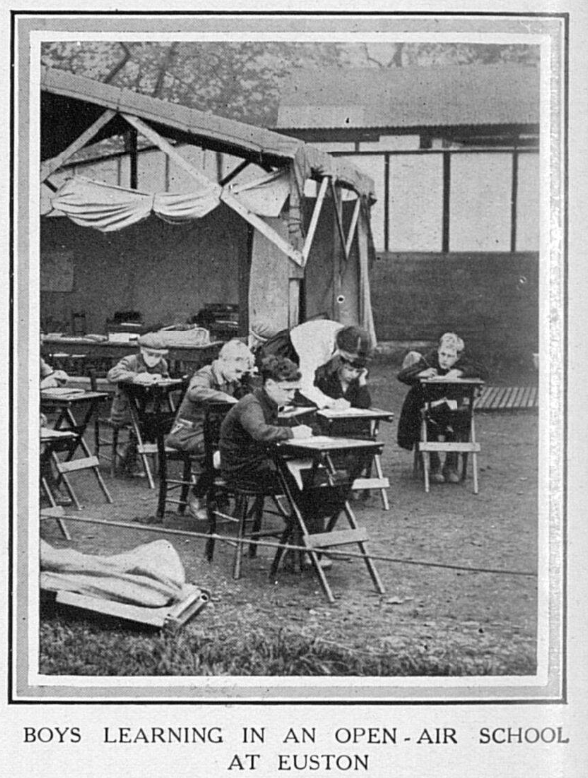

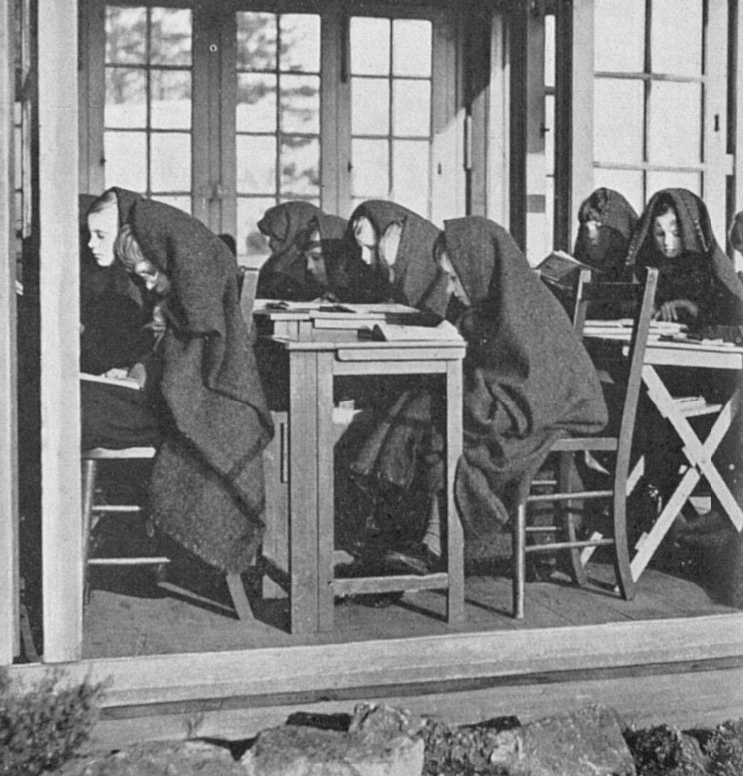

In 1933 the same publication published a deep dive into open air schooling, vividly setting the scene for its readers:

When most of us were shivering in the bitterly cold days of January, when the frosts were hard, and the thermometer remained below freezing all day, there were some hundreds of children in London who were sitting in the open air doing their lessons. Of course, they were warmly clad, wearing their big coats, and with blankets wrapped round their knees: but there they were, out in the open, with no artificial heat.

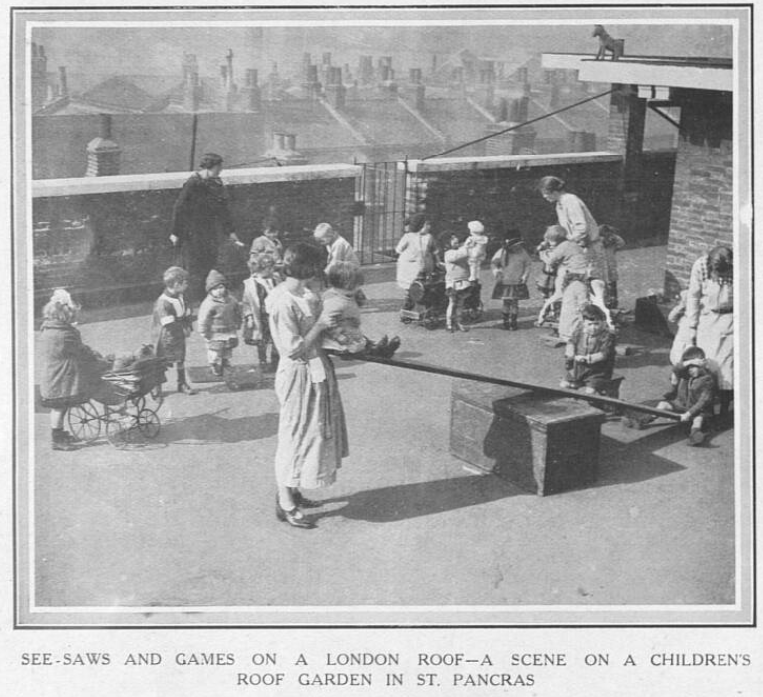

By this point in time, there were ‘different kinds of open-air schools – those for children who have definite signs of tuberculosis, those for anaemic or generally debilitated children, and residential open-air schools to which children are sent who require country air convalescence.’ Alongside these open air schools, open air classes were also held, which could be found ‘in the playgrounds, and on the flat roofs of the ordinary elementary schools, and in the parks – the most enviable being the one in St. James’s Park, where the children have their lessons under the shade of the trees.’

As for the tuberculosis schools, these were for:

….children who have been notified as suffering from the disease and who would be prevented from attending an ordinary school. Many of them have already had a period of sanatorium treatment, and if the disease becomes active again the tuberculosis doctor in attendance recommends their return to a sanatorium again. Their health is watched closely, temperatures being regularly taken, but in most other respects the methods are largely those of the ordinary open-air school…

Finally, the residential open air school performed ‘the part of a convalescent school, bracing up children who need a change of air.’

Daily Routines

But what did these open air schools look like, and what sort of routines were followed at them? The Sphere was on hand to explain:

In the summer the children arrive at nine o’clock in the morning and stay until six o’clock in the evening, during which time they are supplied with breakfast, dinner, and tea….The hours at school are longer than at the ordinary elementary school (there is even attendance on Saturday mornings), but there are long intervals for rest, and the day’s work is very varied, boys and girls working in the garden and helping to make things for use in the school besides the time spent on physical exercises and organized games.

The publication also took the time to outline what these open air schools looked like, describing how:

Whenever it has been possible the L.C.C. has taken an existing house with a garden of least an acre, on which the shelters are built for the different classes…Long stretches of canvas are supplied which can be put up if the rain is driving very strongly from any particular direction, but as the roofs have deep eaves the rain does not penetrate except under exceptional circumstances. Rain is not regarded as any difficulty, it is only fog and very extreme cold which send the open-air children indoors.

The effects were positive, the piece describing how ‘it is extraordinary how soon the pale-faced child, who has no appetite at home, gets used to the new conditions, eats his food among the other children without any fuss, to the great surprise of the parents.’

Beyond The Second World War

Even after the Second World War, open air schools continued to be opened and used. The Torquay Times and South Devon Advertiser on 21 September 1951 reported how:

The Ministry of Education has approved the Watcombe open-air school whose siting at Steps Cross was the subject of contention at Torquay Town Council’s last meeting. The news was announced by Mr. R. W. Turner (chairman) at Wednesday’s meeting of Torbay Divisional Education Executive, and he added the hope that the school would be started next year.

Children in the 1950s were still seeing the benefits from open air schools, as evidenced by the West London Observer in July 1957. The newspaper described the visit of former Medical Officer of Health for London and honorary physician to King George VI Sir Allen Daley to the Wood Lane Open Air School for ‘delicate children.’ He remarked:

‘I am happy to see so many young Londoners being restored to health among such lovely surroundings. Children are like flowers. They need fresh air and proper nourishment. They get both here.’

Meanwhile in Birmingham, officials were looking at extending the number of open air schools in the city. As reported by the Birmingham Daily Post in September 1957, Principal School Medical Officer Dr. H.M. Cohen outlined how ‘there is justification for regarding increased provision of open-air school accommodation for many of these children who are in an unsatisfactory condition.’ He explained:

‘The condition is often of a temporary nature, and those who attend the open-air school are restored to full health and are able to return to normal full-time education.‘

However, as the general health of the population improved, and tuberculosis cases decreased thanks to the use of antibiotics and the inception of vaccination programmes, the need for such open air schools to educate unwell children became less and less. Today we can trace their legacy in forest schools, bringing children back to nature in order to provide them with a different type of education, outside of the classroom. But, The Archive helps us to explore the phenomenon of the open air school in the twentieth century, showing us how they were of benefit to so many children.

Find out more about open air schools, the history of education, and much more besides, in the pages of our Archive today.