In the late 1930s a newcomer made her way onto British cinema screens: Princess Kouka. From Sudan, Princess Kouka, born Tahia Ibrahim Belal, had been spotted by film producer Walter Futter, who was determined for her to appear in his next film.

Using newspapers from the time, we uncover the legacy of this largely forgotten film star, who travelled to Britain and impressed audiences across the country.

‘A Notable Newcomer’

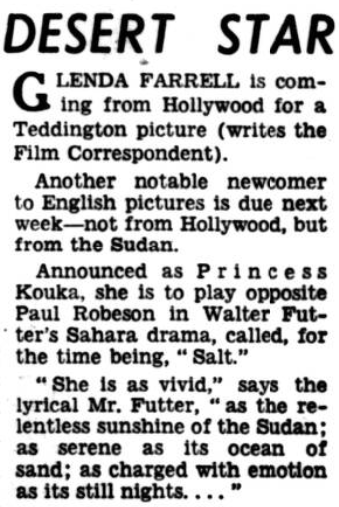

On 18 December 1936 London’s Daily News reported on the impending arrival of ‘another notable newcomer to English pictures’ – Princess Kouka. But unlike her peers, Princess Kouka was not arriving from Hollywood, but from Sudan.

The newspaper described how Princess Kouka was ‘due to play opposite Paul Robeson in Walter Futter’s Sahara drama, called, for the time being, ‘Salt.’’

The new cinema star was due to arrive in London at some point during the following week. Her arrival to Britain was heralded by film producer Walter Futter’s ‘lyrical’ praise, the Daily News describing the producer’s impressions of the princess:

She is as vivid…as the relentless sunshine of the Sudan: as serene as its ocean of sand; as charged with emotion as its still nights…

‘She’s Got What It Takes’

But who was this newcomer to the world of cinema? The Western Morning News on 23 December 1936 gave its readers an insight into Princess Kouka’s background, as the new star arrived in London:

Princess Kouka, who was born in Elfasher, a township over which her father is chieftain, had never before been out of Africa. She speaks only her native dialect and French, which she picked up from a governess, under whose care she has been for many years. She does not drink or smoke.

Princess Kouka was born in 1917 in Cairo, and lived in al-Fashir, the capital city of North Dafur, Sudan. But how did she come to the attention of film producer Walter Futter? The Western Morning News was hand to explain, describing how:

The Princess’s departure from her native land came about through a visit to Africa of Mr. Walter Futter, the producer, who was searching for film locations for the picture ‘Jericho.’

The Daily News on the same day elaborated on Futter’s encounter with the princess, relating how:

Princess Kouka crossed swords with her father to be allowed to come to England when Mr. Futter, seeing her for a few minutes, said: ‘I must have that girl for my new picture. I don’t care if she doesn’t speak English. I don’t care if she has no experience. She’s got what it takes.’

A Clash of Cultures

Princess Kouka had some work to do in persuading her father to let her star in Walter Futter’s picture, which had the working title of Salt but would be released as Jericho. The Western Morning News related how when Princess Kouka ‘was first invited to come to England to play in the film her father refused his permission, on the grounds that it was not fit work for a girl of such noble birth.’

However, national newspaper the Daily Mirror on 23 December 1936 reported how ‘Princess Kouka cried and cried – till [her] father just had to give in.’ According to the article, Princess Kouka’s father, Sheikh Ibrahim Mahdi, feared how she ‘would have to dance with no clothes on in front of everybody.’ Indeed, Kouka herself described her father as ‘very strict and religious,’ but she was able to ‘make him see her point of view – in the end.’

According to the Western Morning News, Princess Kouka ‘had been interested in acting for a long time.’ And so it was that she gained her father’s permission to leave, travelling at first to Paris. In that city, the young woman who was not allowed to wear makeup at home painted her nails scarlet ‘to match the colour of her lips,’ as reported the Daily Mirror.

Princess Kouka Arrives in London

With Princess Kouka’s arrival in London on 22 December 1936, she became the object of intense curiosity. Alongside such curiosity came the almost fetishization of her exoticness, her otherness, with articles also poking fun at such things as her diet.

The Daily News on 23 December 1936 describes how the cinema newcomer met the press in Claridge’s:

She sat talking French with the guttural Arab pronunciation to a circle of newspaper men and women. She was dressed in a pleated skirt of scarlet silk that swept from a high waist to the curved-up toes of her Eastern shoes. A sash of crimson slashed with white was round her hips. Between the red of her dress and the bright silver-striped blue of her bolero jacket flowed the thick white satin of her petticoat.

Her dress and her appearance were alien to a British audience, the report going on to relate how:

Bound about her back, centre-parted hair was a veil of gold lace threaded with blue silk cord, which she called her ‘turban.’ Her neck was circled with a collar of red and yellow gold. From her ears swung flat gold hoops three inches in diameter.

During this junket Princess Kouka was asked about her taste in food. When confronted about the consumption of camels, however, she seemed more than a match for her interviewers. The Daily Mirror reported how:

The Princess has an acquired taste in food. Camels and chocolates are her favourite delicacies. She wrinkled her nose at the caviar sandwiches and filled in the gaps with chocolates – camels being hard to come by in London. I asked her what the humps tasted like, but she raised her eyebrows at me.

‘Remarkable Progress’

Princess Kouka was in London for a reason, however, and that reason was for her to learn enough English so that she could deliver her lines in Jericho.

The Daily News on 16 January 1937 was disparaging about Princess Kouka’s linguistic abilities. In a piece entitled ”In Town Tonight’s’ Worst Moment,’ the newspaper examined her recent appearance on B.B.C radio show ‘In Town Tonight.’ The concept of this programme involved A.W. Hanson ‘holding up traffic’ to interview the ‘interesting people’ who were in London.

Hanson had interviewed 2,000 people in this way, but Princess Kouka was apparently one of the ‘most trying character of recent weeks.’ The piece describes how:

Not a word of English did she speak, yet listeners understood her perfectly. She had learnt her script from Hanson and then copied it down phonetically in Arabic characters which she read in the studio.

Despite the language gap, it seems the actress performed admirably. Moreover, admiration for Princess Kouka’s ability was evident in the press only a few months later. The Kentish Express on 9 April 1937 reported how Princess Kouka had:

…made remarkable progress in the few weeks she was here but, as well learning the language, she learned — in the most civilised town in the world, possibly – some barbaric customs quite new to her – as for instance, the wearing of clothes which shamelessly revealed the ankles!

The Era on 8 April 1937 echoed this sentiment, reporting how:

Princess Kouka scarcely knew a word of English before she came to this country. Now she can say ‘Sure!’ and ‘Okay!’ as well as any of us.

‘Princess Kouka Here Again’

In April 1937 Princess Kouka returned to England, fresh from filming with Paul Robeson in Egypt. The Kentish Express reported how she was back in Britain ‘to complete the film in the new Pinewood studios.’ But things were a little different from her first visit, when ‘prosaic London crowds gathered to stare at the beautiful apparition in their midst.’

The newspaper described how:

Three months ago London become acquainted with a striking and glamorous Eastern beauty, the stateliness and dignity of whose walk (in the highly-coloured and romantic robes of her country) contrasted oddly with a child-like curiosity in everything she saw in the shop windows. Now she is in our midst again.

However, it was reported how Princess Kouka had changed her appearance:

…it is rumoured – she will not attract so much attention in the streets on this visit. For the dusky Princess – we hear – is giving up her rich native robes for the homely tweeds of this island. She thinks they’re rather smart – even if they are slightly immodest.

The Shields Daily Gazette on 30 April 1937 had more to say on the actress’s change of clothes, reporting how:

Princess Kouka, Soudanese film discovery, has discarded her royal robes for European dress. ‘My father would be very angry if he could see me,’ she says, ‘he would not think it decent.’

Meanwhile, she was interviewed by Daily Mirror reporter Elisabeth Rowley in April 1937. The reporter thought that Princess Kouka would have made ‘a good suffragette,’ whilst the Sudanese star was described as saying, regarding ‘English towns:’

‘I would be afraid to go alone in your streets. There are so many cars and people I should certainly get lost or killed.’

‘A Very Fine Performance’

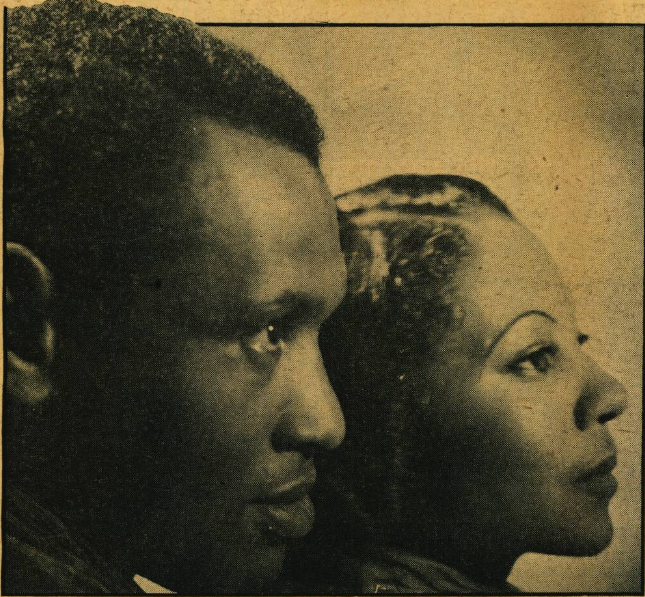

Soon, Princess Kouka’s film debut would be coming to cinema screens across the country. The Daily Mirror on 23 October 1937 gave a preview of her role in Jericho, alongside Paul Robeson, picturing the pair in its pages.

For the Worthing Herald, 8 January 1938, Jericho was ‘Paul Robeson’s triumph,’ the newspaper noting how ‘a real Sudanese princess has a leading role’ in the film. The film featured pioneering African American actor Paul Robeson as a medical student who had been drafted into the American army in the First World War. His troopship is torpedoed, and Robeson’s character Jericho Jackson heroically saves men who had become trapped. However, in the melee, he accidentally kills his superior officer, and is later court-martialled. He escapes, and travels to North Africa, where he comes across the Taureg people.

This is where Princess Kouka comes in. She plays the ‘chieftain’s daughter,’ whom Robeson’s character goes on to marry, as he becomes the ‘virtual chief.’

Meanwhile the Worthing Gazette on 12 January 1938 previewed Jericho as well, and its ‘vivid Sahara scenes.’ The review labels the cast as one of ‘exceptional talent and reputation.’ For her first appearance in an English-speaking role, Princess Kouka was praised for giving a ‘very fine performance.’

But what of Princess Kouka after Jericho? From 1938, she is hardly mentioned in our newspaper collection. She did, however, go on to have further film roles, although not in Britain. She starred in Egyptian films Rabha and Mughamarat Antar wa Abla in the 1940s, and passed away in 1979, in Cairo. Her visit to Britain and appearance in a British film is largely forgotten, lost to time, a passing curiosity. However, Kouka’s legacy deserves to be recognised today: as a Black woman, she came to Britain to participate in an overwhelmingly white industry, and stood out in a society that often objectified her. She is a true trailblazer, and we can remember her through the pages of our Archive.

Find out more about Black performers, cinema history, and much more besides, in the pages of our newspaper archive today.