In this special guest blog, David Musgrove, content director for BBC History Magazine and HistoryExtra, considers the amazing life of the now-forgotten Victorian showman, athlete, and wheelbarrow pedestrian Bob Carlisle, and how his clever manipulation of newspapers marks him out as a 19th-century influencer.

Did the Victorian period have influencers? Yes, but rather than using social media and camera phones, they employed letter-writing and wheelbarrows.

I’ve been researching the story of a forgotten 19th-century minor celebrity whose life was widely reported on in the newspapers of the day. And a big reason for the coverage was that the man in question was a talented self-promoter, who knew how to curry favour with the newspaper editors and journalists.

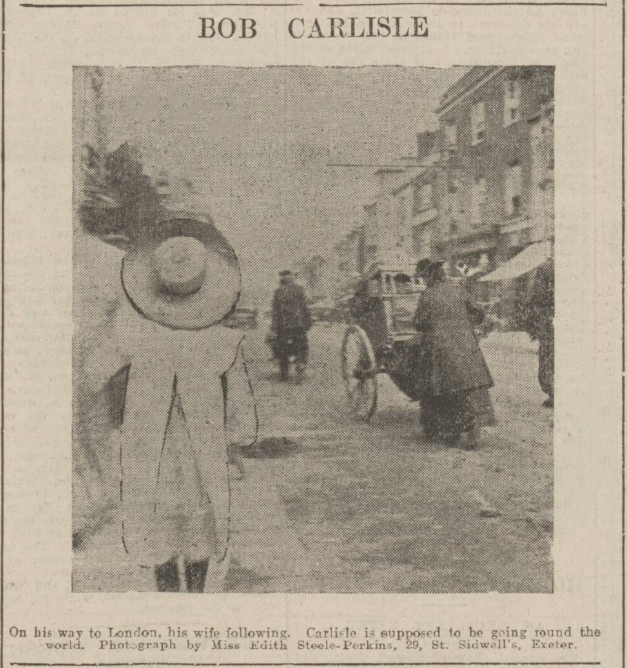

His name was Bob Carlisle, and his big claim to fame was that he was the “original wheelbarrow pedestrian”. Pedestrianism, in other words competitive walking and running, was a big deal in the Victorian period and a very popular sport. In 1879 Carlisle innovated, and added a wheelbarrow to the mix. He was the first man to push a wheelbarrow from the western tip of Britain, Land’s End, right to the north, to John O’Groats (and back).

He set out to walk over 30 miles a day (excluding Sundays), pushing his wheelbarrow, which was adorned by a fluttering Union Jack on a small flagpole. He commenced his journey in October 1879 and completed the there-and-back walk of over 2,000 miles by mid-December (72 days of walking). The newspapers lapped up his eccentric adventure, and if you search on ‘Wheelbarrow Pedestrian’ for the year of 1879 in the British Newspaper Archive, you will see a wealth of reports on his progress.

Carlisle’s stated aims for doing this wheelbarrow challenge were several: he wished to position himself as a challenger to a very famous American pedestrian, EP Weston, who had recently travelled through Britain on a mammoth walk himself (without wheelbarrow), to great acclaim and huge crowds. Carlisle set out to demonstrate that a Scotchman (his wording; he was born near Edinburgh) could match the American. He also started off by wishing to demonstrate the benefits of teetotalism (though he changed his tune by the end of the walk and was advocating instead moderate consumption of alcohol for endurance exercise). Finally, he did it because he’d been out of work for months previous, and though he said he wasn’t doing the walk for a wager, he was certainly hard-up money-wise and I’m sure he saw an opportunity to earn both fame and fortune from the endeavour.

To make a success of a venture, Carlisle needed the newspapers – which at the time were ubiquitous and the key source of news for people – to write about him. He had the advantage of novelty, in that pushing wheelbarrows long-distances was not a regular activity (though he did borrow the idea from two Americans who had just walked from the east to the west coast with barrows). However, he was also, I think, very proactive in making sure that the papers knew that what he was up to. There is direct evidence (albeit from later walking challenges he undertook) that he was writing to newspaper editors to ask them to cover him. I think that when he stopped in the towns on his route, he paused to post letters and send telegrams to editors with newspapers covering the places he was shortly to visit to tell them of his approach.

He knew all about the art of promotion because in a previous career, he had worked as an agent-in-advance for travelling circuses. That role meant that he went ahead of the circus to the next town to be visited and drummed up interest in ticket sales by bill-posting and no doubt talking to the local media outlets.

Carlisle used this experience of promoting circuses to promote himself. But he enjoyed numerous other roles in the world of the travelling show – notably, he also worked as a clown and a lion-tamer. One of the reasons why he’d been out of work prior to his wheelbarrow mission was that he’d been relieved of his big cat role in the circus for ill-advisedly walking down the street in a Cornish town with an unmuzzled tiger on a lead.

Anyway, he was clearly a great showman and not afraid of public performance. That was another element of his wheelbarrow media strategy, in that he made sure that he gave the newspaper journalists something to write about – he was good copy. At most of the towns he stopped at, he delivered a talk, sometimes impromptu on the steps of the town hall, but sometimes planned and booked in a venue. He also clearly went out of his way to talk to the journalists and give them some quotable material. His lecture topic was a review of his remarkable life (as well as a circus showman, he’d spent years sailing the world in the navy and merchant fleet, seeing many things and getting in many dramatic scrapes), along with an exposition on the value of temperance.

The combined impact of the eccentricity of his endurance endeavour and his skills in self-promotion and media management meant that he was regularly and widely reported on in the local newspapers, mostly in positive terms. To that extent, he feels to me like an early example of an influencer. In fact, we can see that he did directly influence others to take up the wheelbarrow-walking challenge. An entry in the Edinburgh Evening News of Friday 14 November 1879 for example reports that two boys (8 and 11 years old) had walked from Newcastle to Sunderland with a wheelbarrow. Though the lads themselves were unable to explain why they had done this, the journalist surmised that “they must have heard of the walk from John O’Groats House to the Land’s End”.

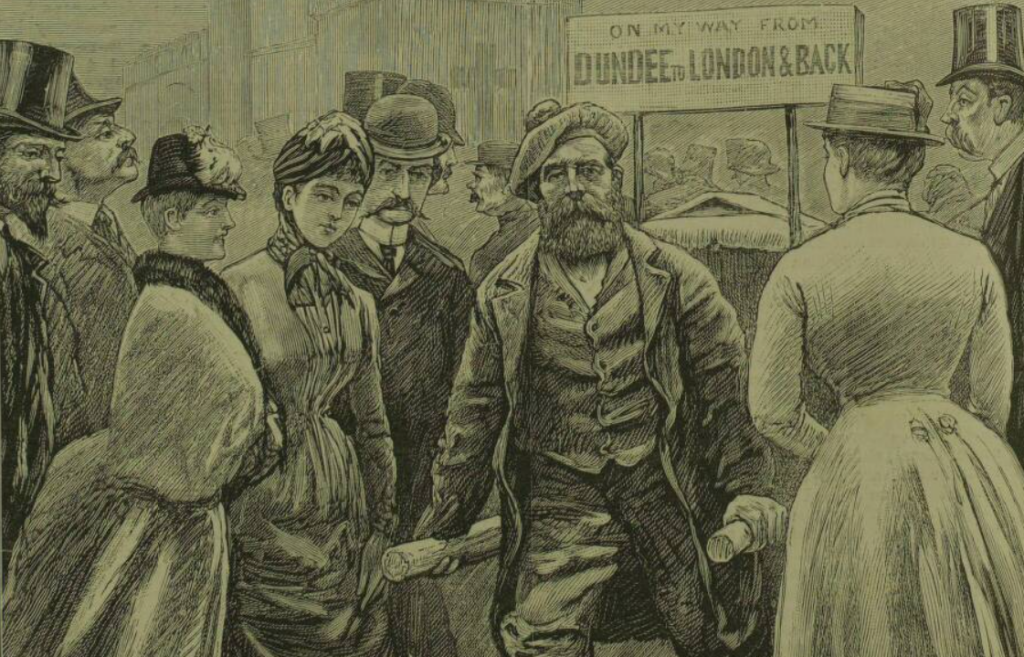

Carlisle’s biggest influence though came a few years later, in 1886, when the so-called Wheelbarrow Craze hit the nation. It started when the Newcastle Evening Chronicle latched onto a rivalry between a man called James Gordon, who had started pushing a wheelbarrow from Dundee to London, and another wheelbarrowist, the marvellously named Sawdust Jack, who had commenced chase on him from Newcastle. This created a brief press explosion and led to a charge of people pushing wheelbarrows from Scotland and north-east England down to London. Bob Carlisle, the original wheelbarrow pedestrian and surely the inspiration for this moment, sadly missed the whole thing as he was thousands of miles away on a cargo ship.

Again, newspapers were heavily involved in building up the wheelbarrow craze, and Gordon employed similar tactics to Bob Carlisle in writing to the local papers to tell them of his progress and forthcoming route. You can track the rise and fall of this short-lived wheelbarrow craze on the British Newspaper Archive.

You can also read more about the Great Wheelbarrow Craze of 1886-87 in an article in the March issue of BBC History Magazine, on sale in February 2024, also available on the magazine’s website www.historyextra.com.

You can listen to a six-part podcast series, entitled The Tiger-Tamer who went to sea, all about the amazing life of Bob Carlisle, and his adventures as a globetrotting seafarer, circus showman, clown and lion-tamer, and astonishing wheelbarrow endurance athlete on the HistoryExtra podcast from Thursday 22 February. The podcast series tells Carlisle’s story and includes interviews with a cast of leading historians considering how his life informs us about wider themes in Victorian history, such as celebrity culture, media influence, leisure and entertainment, and global trade and shipping.