Here at The Archive, we love to learn of the discoveries you have made through our newspaper pages, and how you have used them, whether they have influenced novels, or provided information for dissertations. We were incredibly grateful, therefore, when crime writer and athletics historian Peter Lovesey contacted us with his account of sixty years of researching newspapers. From accessing historical newspapers in their original form, to scrolling through microfilm reels, and finally to searching newspapers digitally on the British Newspaper Archive, we hope you enjoy Peter Lovesey’s remarkable story of his life and career told through the lens of his newspaper research.

One Saturday morning in 1963 I visited the British Library’s national newspaper collection at Colindale, way out on the Northern Line. My mission was to find out more about a Native American called Deerfoot who came to Britain in 1861 to challenge the best British distance runners, He stayed for two years, touring the nation and setting new records. I had only ever seen a picture and a couple of sentences about him in an old book.

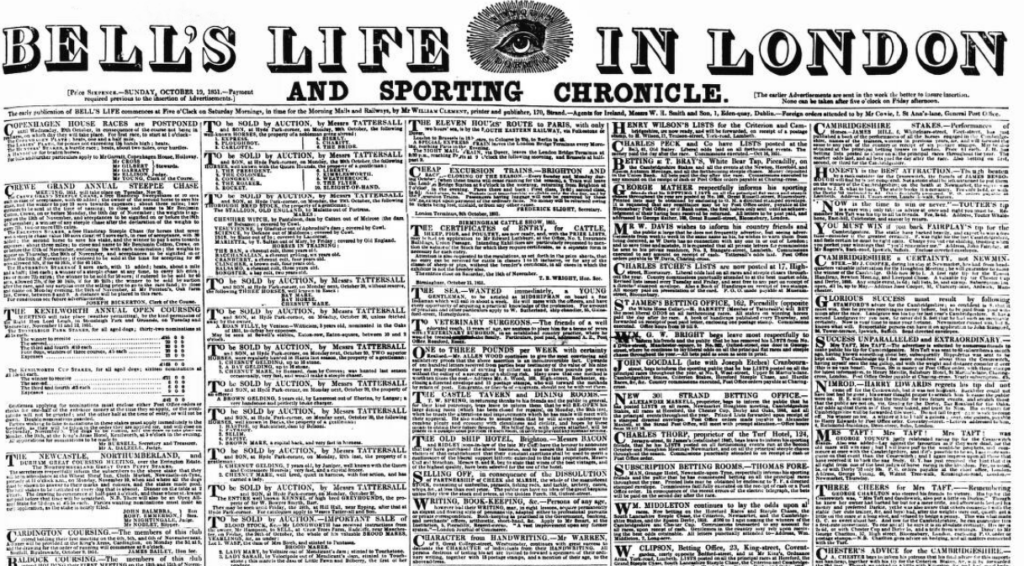

In the reading room at Colindale, I soon figured out the system of using the catalogue and ordering the bound volumes of Bell’s Life in London and Sporting News that after about fifteen minutes were trundled out on a trolley from the inner depths where only the staff were allowed. Once the original newspaper was in front of me, I experienced the closest thing to a time machine I had ever experienced. Turning the dry, yellowy pages, I was transported back a hundred years. I don’t know whether those nineteenth century reporters were paid on the penny-a-line system, but the writing was rich in detail, far better than I could have wished for.

To cut to the chase. I went home and wrote an article about Deerfoot and hawked it around sports magazines until someone published it. I wasn’t paid. The glamour of being in print was enough. For some years after, I was a Saturday regular in the reading room and wrote numerous articles about the forgotten athletes of a century before. And in 1968 I got up the confidence to write my first book, The Kings of Distance, about five great runners, starting with Deerfoot. The foreword was written by Harold Abrahams – later immortalised as the Ben Cross character in Chariots of Fire – who had seen my articles and become a friend.

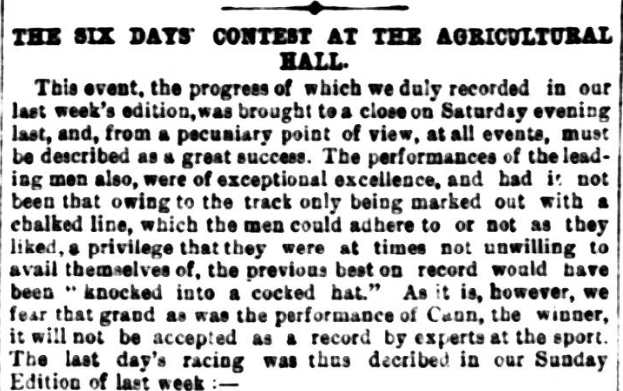

Becoming an author was a new high for me, but having ‘done’ distance running, what else could I write about? The chance came along in 1969 when the publishers Macmillan announced a first crime novel competition for a prize of £1000, more than my salary as a teacher. My wife Jax, who read whodunnits at the rate of two or three a week, said, ‘Give it a go. Use your knowledge of athletics. If nothing else, it will be different from any crime story I’ve seen.’ I racked my brain and remembered reading in Bell’s Life about six-day races indoors at the Agricultural Hall, Islington, in the 1880s, a new twist as a setting, but not so different in structure from one of those country house weekends that worked so well for the likes of Agatha Christie and Dorothy L Sayers.

Back I went to Colindale, where I found masses of material to enrich the story: the characters who entered the contests, the trainers whose main job seemed to be keeping them awake and giving them stimulants, the betting men, the backers and the saboteurs who filled certain competitors’ boots with crushed walnut shells to give them blisters or added a laxative to the food they ate. The press called the races ‘wobbles’. I had more than enough material for my competition entry. I introduced murder and a Scotland Yard sleuth called Sergeant Cribb. I sent off Wobble to Death, and to my surprise and delight, it won the prize.

The publishers asked for more, so I provided it at the rate of a book a year about Sergeant Cribb’s investigations, each one based on more research at Colindale into topics like bareknuckle boxing, the music hall, spiritualism, the seaside and boating on the Thames – all big Victorian enthusiasms. After the first five books, I was earning enough to give up the day job and become a full-time author. That was 1975, half a century ago, and I am still writing thanks largely to the limitless inspiration I got from the old papers.

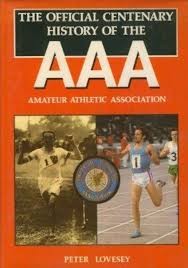

In 1979, thanks mainly to my friend Harold Abrahams, I was invited to write the History of the Amateur Athletic Association, which was 100 years old in 1980. By then I knew my way around the newspaper collection and spent many hours in the reading room. The technology had moved on. Most of the papers were put on microfilm and there were rooms at Colindale where you could use microfilm readers, at first cranking them by hand to get the pages you wanted and later pressing controls that moved the film for you. As well as mugging up on the key events, I collected and used lovely old drawings from the Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News.

At about the same time, I had the good fortune to get the Sergeant Cribb novels onto TV. The opening sequence used stills from the Illustrated Police News, which was a nice nod to newspapers as the source and inspiration of the series. By then, the British Library was selling microfilm to libraries all over the country and I saved on fares by doing my research nearer to home than Colindale. The next development for me was made possible by one of my books being bought by Hollywood and turned into a film that is best forgotten, but with some of the money I bought my own microfilm reader and ordered complete runs of microfilm from the British Library. They were stacked high in cartons in my small office. The whodunnits I wrote were often praised for their period detail. This was thanks entirely to my secret support system.

When everything went online about 2011 and the British Newspaper Archive was launched, I became a subscriber at the earliest opportunity. As the papers in my own collection were digitised, I was able to move those bulky cartons out and make space in my crowded office. The luxury of having everything on computer is a joy. And the search facility is wonderful, opening vast new possibilities.

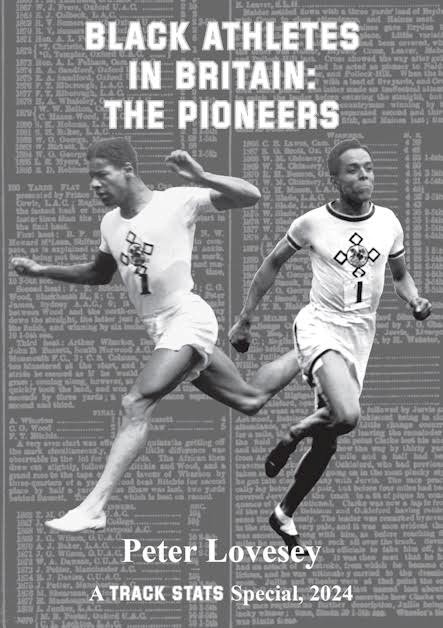

I made my living from writing for half a century and produced 43 novels and 6 short story collections. Against the Grain, published in November, has to be my last, as I am 88 now, with terminal cancer. Between books I continue to research and write about athletics history, which is more of a hobby than a source of income. I’m rather proud of my latest venture, a booklet for Black History Month called Black Athletes in Britain: the Pioneers. It tells the stories of 35 men and women of colour from 1811 to the 1920s, nearly all of them unknown to modern followers of the sport. It would have been quite impossible without my life support, the British Newspaper Archive.

Peter’s website is www.peterlovesey.com.