This week at The Archive we are delighted that iconic story magazine the People’s Friend has become our friend, as we are joined by the first 59 years of the long-running Scottish title. Before we delve into the history of the wonderful People’s Friend, and explore one of its first ever stories, ‘Faithful and True,’ which appeared on its inaugural front page on 13 January 1869, we also wanted to celebrate the addition of 291,950 brand new pages, which have taken us over the 88 million pages mark. Meanwhile, from Belfast to Bexhill, from Lancing to Larne, from Wigan to Worthing, we’ve updated 29 of our existing titles this week.

Register now and explore the Archive

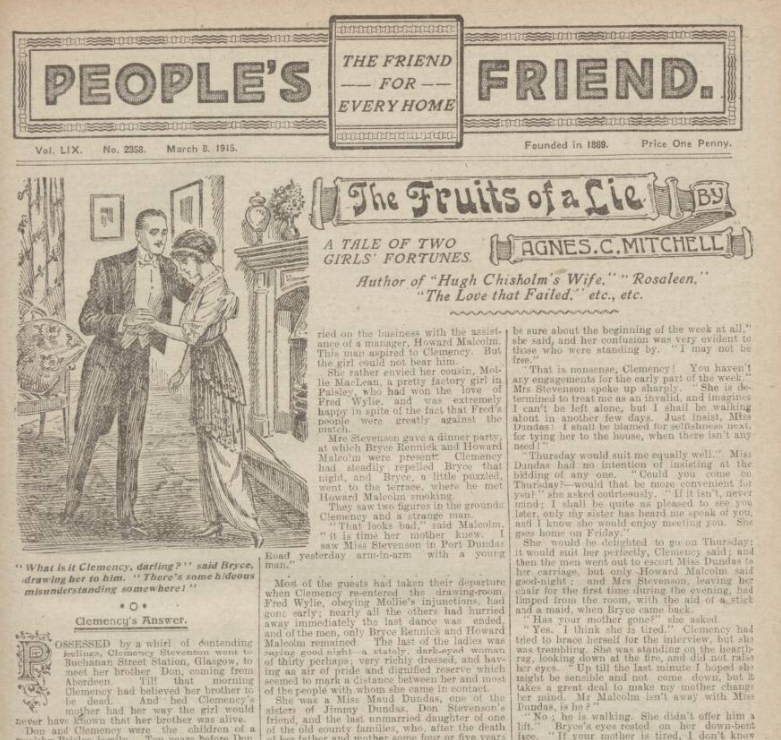

We are delighted this week to be joined by one of Britain’s longest-running magazines, ‘The Home of Great Reading,’ the People’s Friend. Published by D.C. Thomson, the People’s Friend was founded by newspaper proprietor and politician John Leng (1828-1906) in 1869, as an offshoot of the Dundee People’s Journal, itself established in 1858.

John Leng’s association with Dundee newspaper publishing began in 1851 when he was appointed editor of the Dundee Advertiser. He then went on to found Scotland’s first ever half-penny daily newspaper the Daily Advertiser, a short-lived endeavour, before he found more success with the Dundee People’s Journal, a weekly newspaper, which quickly gained great popularity. The People’s Friend, which first appeared on 13 January 1869, was an offshoot of the popular newspaper.

Priced at one penny, the first edition of the People’s Friend was labelled as a ‘Monthly Miscellany in connection with the ‘People’s Journal.” Filling some sixteen pages, the debut edition of the People’s Friend featured a range of stories, as it aimed to showcase the ‘contributions of the intelligent working men and women of Scotland.’ Indeed, the People’s Friend was created as a platform for amateur writing, influenced by the submissions received by its sister title the Dundee People’s Journal.

The inaugural editorial of the People’s Friend tells of how a prize competition for writing, set up by the Dundee’s People Journal, garnered some 633 entries. 157 of these came from novelists, whilst 419 of the entries were from poets, and 59 were submitted by ‘juvenile letter writers.’ Herein lay the inspiration behind the People’s Friend. It was destined to be a place where the writings of ordinary people could be showcased, as the editorial stated: ‘we shall have pleasure in opening the columns of the FRIEND to the contributions of the people.’

Not only was the People’s Friend to represent the writings of the people, it was to focus, very deliberately, on all things Scottish. ‘Preference’ would be given to ‘Scottish stories, poetry and other articles, written by Scotchmen,’ and women, we should add. The People’s Friend would also feature extracts from books, as well as presenting special sections devoted to ‘The Housewife,’ ‘The Gardener,’ and to young readers. Family values, or ‘fireside reading,’ would be incredibly important to the nascent People’s Friend too, which would be carried forward many decades after its debut.

So popular was this format, that by 1870 the People’s Friend had switched to a weekly publication schedule, appearing every Wednesday. As the decades progressed, the publication began to feature more and more illustrations, developing its trademark for drawings of beautiful landscapes, particularly incorporating Scottish scenery. The People’s Friend also began to feature works by the likes of Annie S. Swan (1859-1943), a writer who was known for her romantic fiction, but also for her Liberal activism and support of the women’s suffrage movement.

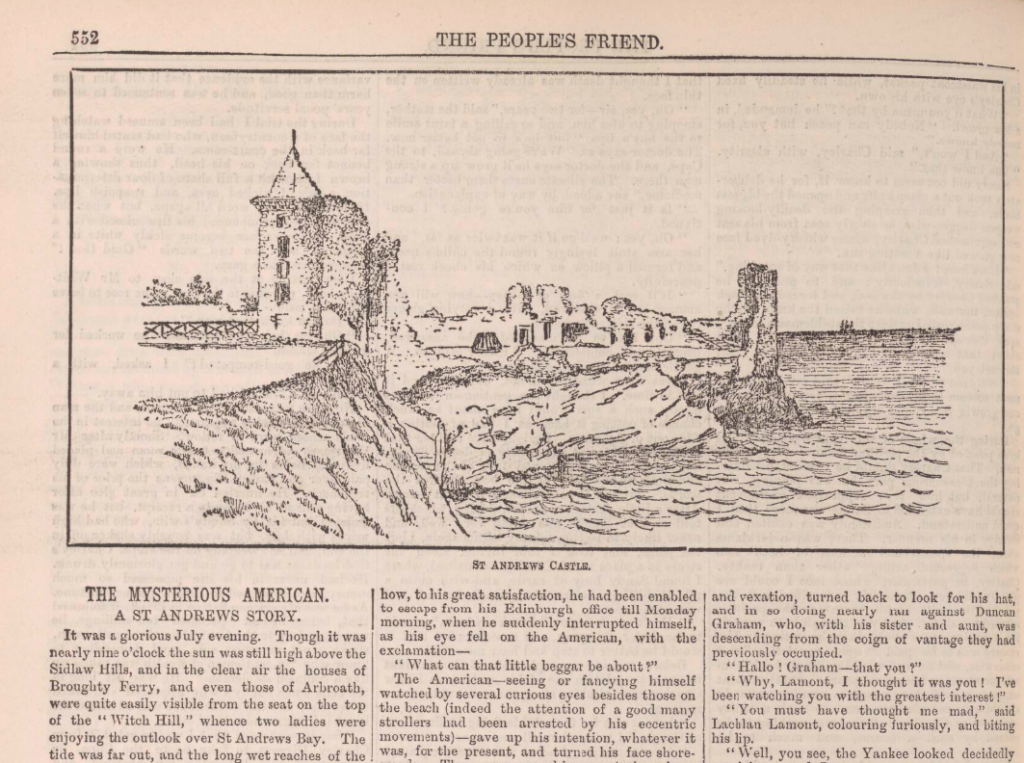

Meanwhile, the People’s Friend stuck firmly to its Scottish roots. Its stories had a firm Scottish lean, with such tales as ‘The Mysterious American – A St Andrews Story,’ ‘Seeking Treasures in the Pirate’s Isle; or Tales Told During A Tour in Shetland,’ and ‘Love at Last – A Romance of Carnoustie‘ featuring in its pages.

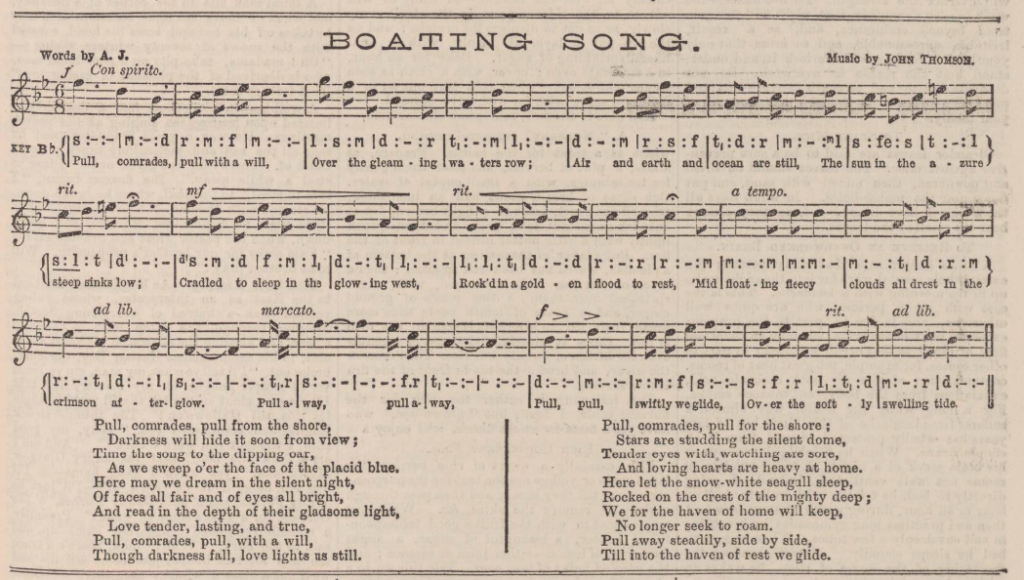

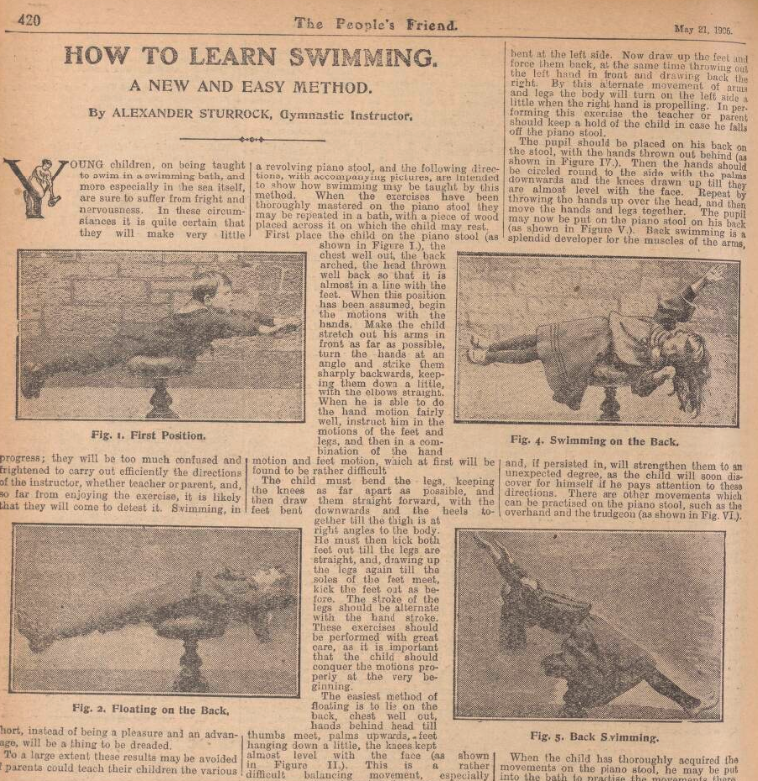

However, the People’s Friend was more than just a story paper, as it featured a range of other articles. It printed musical scores, so you could play or sing the latest tunes, whilst also featuring a ‘Violin Players’ Column.’ The publication was also strong on educating its readers, printing articles on a wide range of different subjects. From ‘Fighting in the Air – How Flying Machines Engage in War‘ to ‘How to Learn Swimming,’ from ‘Coin of the Realm‘ to ‘Pretty Girls Who Walk Badly – How to Cure Faults,’ the People’s Friend ensured that is readers were well educated on a range of different subjects.

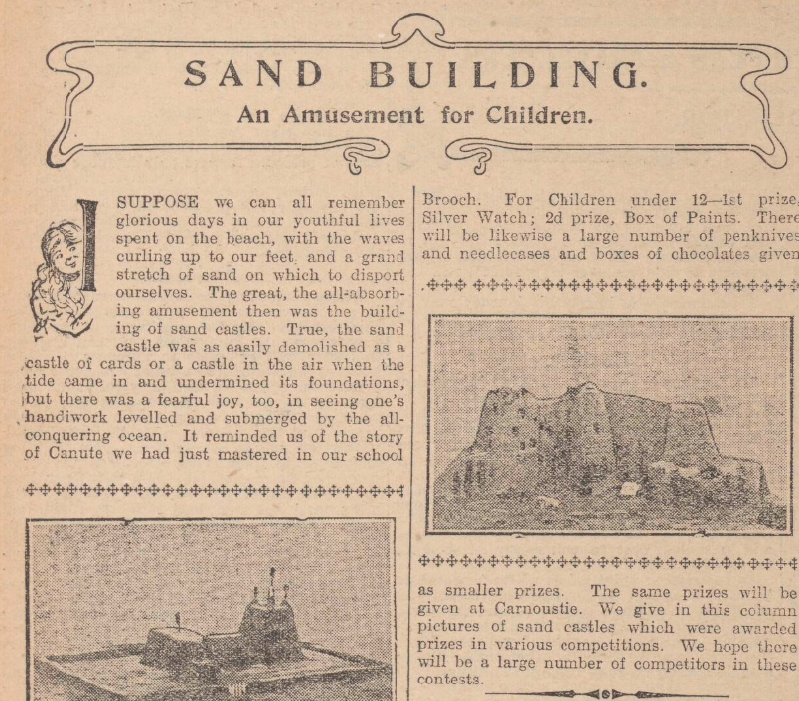

As time went by the People’s Friend also began to devote its pages to arts and crafts. For example, alongside providing more traditional sewing patterns, the title also published advice on everything from the art of stencilling to sandcastle building.

Furthermore, the People’s Friend had a strong ‘Household‘ section, which dealt out a range of advice. From printing recipes to detailing how to fold serviettes, from describing how best to ‘renovate‘ old clothes to reporting on the latest children’s fashion, it was a thorough guide for housewives. This particular theme saw the magazine become more and more centred on its female readership, the title’s focus shifting to women in a more pronounced way during the First World War.

For many years the People’s Friend has stuck to its winning formula of family-friendly content, stories and crafts. Still immensely popular to this day, it is remarkable for sticking to is promise of publishing stories penned by the people. The People’s Friend continues to commission over 900 original stories annually, providing an important platform for first time authors.

We are delighted to be joined by the first 59 years of the People’s Friend: watch this space for more.

Meanwhile, we are joined by another new title this week, Lincolnshire’s Louth Leader. Publishing all the latest news from the market town of Louth, which lies in the East Lindsay district of Lincolnshire, as well as from the town of Mablethorpe and the ‘villages in between,’ the Louth Leader was established in the 1980s. Still running to this day, it appears every Wednesday.

Finally, we are joined by updates to 29 of our existing titles this week. You may notice that all of these updates have something in common: they are all from the year 2004. Our largest update of this crop is to the Belfast News-Letter, to which we have added over 23,000 brand new pages, whilst fellow Northern Irish titles the Larne Times, the Coleraine Times and the Derry Journal have also been updated this week. Coming in second and third place respectively are the West Lancashire Evening Gazette with over 22,000 brand new pages and the Sunderland Daily Echo and Shipping Gazette with over 20,000 brand new pages.

‘Faithful and True’ – The First Story Printed by the People’s Friend

Although there are several stories printed by the first edition of the People’s Friend, 13 January 1869, we have given the honour of the first story to be published by the famous magazine as the one that appears on its front page, with the full title of ‘Faithful and True – A Sad Story for the Happy Christmas Time.’

This story, with the Winter’s Tale quote of ‘A sad tale’s best for winter,’ was penned by Glaucus, a name with various ties to Greek mythology. It is written in the first person, across two chapters and six columns, and it tells of the narrator’s visit to the fictional Dolremmet Castle. You can read the full story here, but we will tell it in its condensed form now.

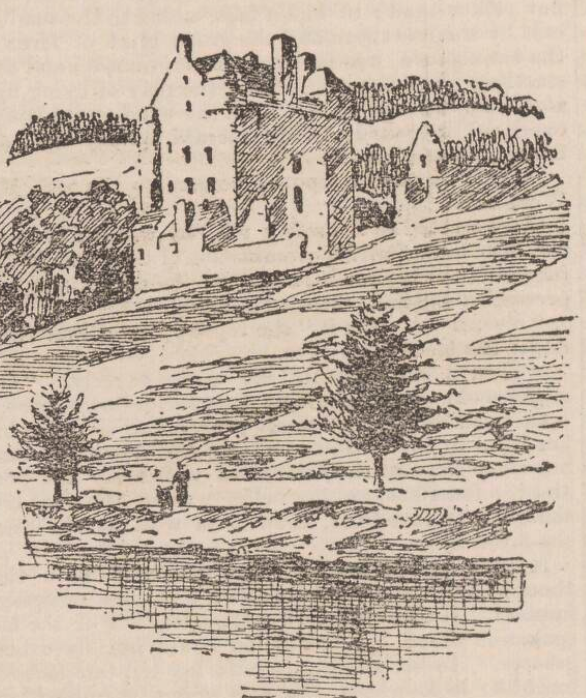

At the castle, the home of an anonymous earl, the narrator meets the earl’s daughter, Lady Edith, and is immediately struck by her beauty. Also at the castle is Lady Edith’s sister Fanny, their cousin and a nephew of the earl Mr. Weir, and an Italian painter, named Rosetti, who was painting a portrait of Lady Edith. It is summer time, and the narrator soon realises that Rosetti and Lady Edith are in love. Rosetti wastes no time; he soon confesses his love of Lady Edith to her father the earl, who replies that ‘it would not be becoming to have him as a son-in-law,’ and besides, ‘he had already promised his daughter Edith to Mr. Weir.’

Rosetti is then forced to leave the castle, and Lady Edith begins her slow decline. The narrator tells of how her ‘only pleasure’ had become ‘caressing her fine St Bernard dog, Roma, which Rosetti had given her before leaving.’ Meanwhile, Lady Edith fills her days by visiting the local post office, waiting for a letter from Rosetti, which never comes.

The months go by, until it is Christmas, and the narrator continues to stay at the castle and to witness Lady Edith’s descent into melancholy. She asks the narrator about Rome and about Italy, whilst he ponders whether or not her ‘lover had proved false to her? Was he dead? Could she bring herself to marry her cousin?’

During this time Mr. Weir was continuing to put forward his case for marriage. However, over the Christmas period, he has a tragic accident whilst riding. He is thrown from his horse whilst jumping over a stone wall, and lands on a ‘heap of sharp stones.’ Mr. Weir is killed instantly, causing the narrator to note how ‘Christmas brought pain and death’ to the castle.

The story then moves to the second chapter, which takes place a year and a half later. The narrator returns to the castle, after hearing from Lady Fanny that her sister Edith is very unwell with a ‘brain fever.’ As soon as the narrator returns to the castle, he finds a bundle of letters addressed to him from Lady Edith. In the cover letter, Lady Edith explains how the late Mr. Weir’s servant had presented her with a bundle of letters written by Rosetti, which evidently had been intercepted at the post office.

Devastated, Lady Edith entreats the narrator to find Rosetti and give him her letters, so that he might know that she was ‘faithful and true to the end.’ The narrator then visits Lady Edith on her death bed. She forgives Mr. Weir for wronging her, and gives the narrator her beloved St Bernard dog, Roma.

Next, the narrator travels to Italy. Three months on to his visit to the castle, whilst in Naples, he hears of Lady Edith’s death, and he decides to go to Rome, on the trail of Rosetti. Whilst walking around the streets of Rome one night, his dog Roma begins pawing on a café door, unwilling to move on. The narrator then enters the café, to find it deserted, barring one ‘silent melancholy figure:’ Rosetti.

Whilst travelling across Lake Como, Rosetti had heard the news of Lady Edith’s passing from some English aristocrats. The aristocrats also spoke about rumours of some ‘intercepted letters.’ Rosetti then goes out for a walk, and comes back, only to fall very ill. He becomes delirious, speaking of the castle and Lady Edith, as the narrator looks after him.

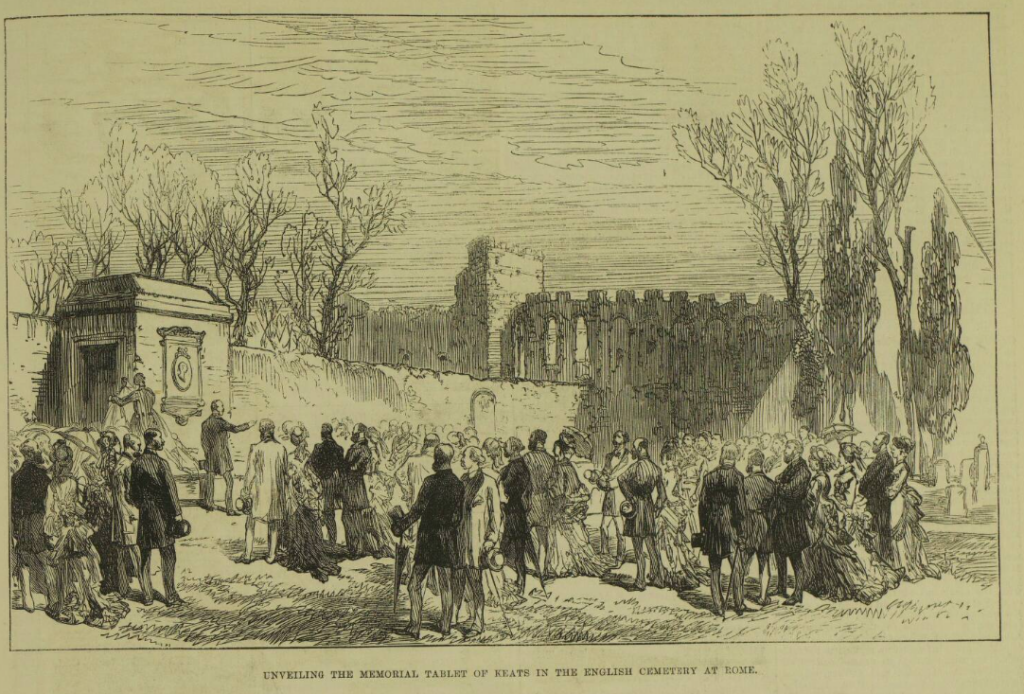

However, Rosetti dies after four days, the narrator noting how he himself had been ‘faithful and true’ to Lady Edith until the end. The narrator then helps to arrange to have Rosetti buried ‘in the beautiful little English cemetery, on a lovely Italian day.’ Years later he returns to pick violets from Rosetti’s grave, which he then plants on Lady Edith’s tomb.

What do you make of this sad tale of forbidden Victorian love? Keen to read more stories like this? Explore the People’s Friend to discover more stories, and much more besides.

New Titles

| Title | Years Added |

| Louth Leader | 2004 |

| People’s Friend | 1869-1928 |

Updated Titles

You can keep up to date with all the latest additions by visiting the recently added page. You can even look ahead to see what we’re going to add tomorrow.