Using newspapers from The Archive, in this special blog we take a look at the history of Charter Fairs, from their inception in the medieval period to their continuation in twentieth century Britain.

In his June 1955 article for The Sphere, entitled A Partial Eclipse of the Fair, Brian Vesey-Fitzgerald notes how ‘Fairs are of very ancient origin,’ and have been part of British life for thousands of years. A Charter Fair was a fair endorsed by the Crown. Crown-issued letters patent gave an individual or a corporate body, like a city borough, the privilege of holding a fair. Soon, fairs began to crop up all over England, often corresponding with a saint’s day and being run by the church. The main four Charter Fairs were spread out across the year in Boston, Winchester, Stamford and St Ives, which saw traders visit from across Europe. By 1516 there were an estimated 2767 fairs in England.

Stourbridge, however, according to the Tewkesbury Register and Agricultural Gazette, was Europe’s largest fair in the Medieval period.

Stourbridge, located in Cambridge, next to the Stour, a small tributary of the River Cam, is believed by some to be one of the oldest of the great British Charter Fairs. Indeed, one scholar suggests that a fair of sorts was held at Stourbridge a thousand years before King John granted the official charter to the Hospital of St Mary Magdalene in 1211.

At one time it was the largest fair in Europe, and lasted three weeks. Defoe found its sights worthy of his pen, and Bunyan wrote his picture of ‘Vanity Fair’ from the experiences of his visits to the Stourbridge Fair. In the eighteenth century £100,000 worth of woollen stuffs were sometimes sold in a week, and in the last century the trade done used to run into five or six figures of pounds sterling.

However, the same article notes how ‘medieval survivals are having a bad time this century,’ as Stourbridge Fair fell into decline, its ‘glories…gone forever.’

The decline of the fair was not a twentieth century phenomenon. After the dissolution of the monasteries, the church’s power waned and thus many fairs, tied to local monasteries and the like, faded from history.

But the Bartholomew Fair, ‘the only really important fair held in London,’ survived the dissolution of the monasteries. It had been founded ‘in the year 1133 by special charter granted by Henry I to his former minstrel, Rahere, now first Prior of the great Priory of St Bartholomew, which the saint had in a vision commanded him to build, and it was held annually on St Bartholomew’s Day in that part of West Smithfield known as the Elms, from the trees that grew there, making of it a pleasant, shady place, much loved by the citizens of London.’

Indeed, it retained its popularity long enough to be written about in a play of the same name by Ben Jonson, who saw the fair as a ‘microcosm of the England of the day.’ The Dublin Evening Mail describes diarist Samuel Pepys walking up and down its alleys, and finding courtesan Lady Castlemain there, ‘at puppet play.’

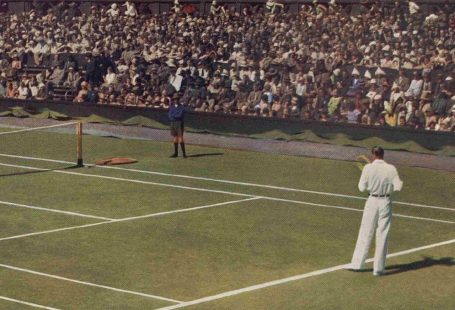

Illustrated London News | 19 May 1923

Illustrated London News | 19 May 1923

But the same 1855 article in the Dublin Evening Mail is something of a savage eulogy on the old fair:

Bartholomew Fair, which has been in an expiring state for some years past, died on Monday last, without exciting care, or sorrow, or attention. The old sinner had no one to console him in his last moments, and so little was he regarded, that no one is likely to take the trouble to write his epitaph.

The publication notes how ‘as the fair grew old, it retained nothing of its former self but its wickedness,’ going even further to label it the ‘annual moral abomination of Smithfield.’

Indeed, ‘Bartemly Fair’ had been described as a ‘Saturnalia of Nodescript Noise and Nonconformity’ by contemporaries, where the ‘Lord Mayor changes his sword of state into a sixpenny trumpet, and becomes the lord of misrule and the patron of pickpockets.’

Illustrated London News | 8 November 1945

Illustrated London News | 8 November 1945

An account in the Illustrated London News gives a truly horrifying account of the Bartholomew Fair:

After sundown, by which time the merchants had finished their business for the day, it was no place for children or gentlewomen, for then pickpockets, cut-purses, and snatchers plied their trade among the drunken crowd, and apple and orange girls, gingerbread men and hot-piemen pressed their wares with bawdy persuasiveness. The noise became intolerable as the crowds increased with the hours, and roughs and hooligans ran amok among the merry-makers, leaving in their train injured women and children, overturned stalls and booths, and scattered merchandise, and, here and there, some menacing piece of flaming wreckage.

This did not prevent the fair from being revived in 1923 to mark the 800th anniversary of the founding of St Bartholomew’s Hospital.

Illustrated London News | 16 June 1923

Illustrated London News | 16 June 1923

Elsewhere in Britain, medieval Charter Fairs continued to flourish. In Boston, Lincolnshire, ‘as great a crowd as ever…gathered outside the Assembly Rooms to hear the noon-tide announcement of the Fair’s Opening’ in 1938.

During the opening of the fair, the town’s Mayor gave an impassioned speech in support of the fair tradition: ‘I feel that in fairs we have something that all classes are determined the carry on.’

Indeed, in 1951 the Lincolnshire Standard & Boston Guardian once again reports that the ritual is going strong, with 9,000 in attendance at the festival’s pageant. Vesey-Fitzgerald observers

that the post-war austerity of the late 1940s and 1950s fuelled this resurgence of the fair, claiming that ‘at least until the end of the 1953 season, fairs were more popular in Britain than at any time since the reign of Elizabeth the First.’