In September 1969, 144 Piccadilly, a mansion in London’s fashionable West End, was taken over by a group of hippies who called themselves the London Street Commune. Over several days, the hippies barricaded themselves in the mansion, and resisted attempts to remove them, in what became known as the Battle of Piccadilly.

Hippies occupy Endell Street School, Holborn | Illustrated London News | 4 October 1969

In this special blog, we look at how the newspapers of the time reported on this hippie occupation, the background and motivations of the London Street Commune, as well as the aftermath of the events of September 1969, using pages taken from the British Newspaper Archive.

Want to learn more? Register now and explore The Archive

The London Street Commune

In mid September 1969, hippie group the London Street Commune had taken over 144 Piccadilly, a three-storey mansion in Mayfair. But who were the London Street Commune, and what did they hope to achieve?

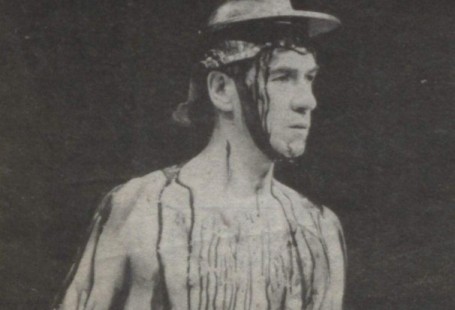

Their leader was history graduate and professed Marxist John Moffatt, who styled himself as ‘Dr John.’ In this article from the Birmingham Daily Post, he explains the background behind the London Street Commune, and their intent in squatting at the Piccadilly mansion:

The London Street Commune was formed to defend the interests of beat groups around Piccadilly and to dissolve control of the streets from the police and back into the community. We want Piccadilly to become a real people’s forum, a forum for the understanding which would act as a resistance against all institutions like the family, the school, detention centres, and so on, which exist to domesticate us compulsorily into the non-values of straight society.

‘Doctor’ John Moffatt | Birmingham Daily Post | 20 September 1969

But the London Street Commune also had the intention of raising awareness of the growing problem of homelessness within the nation’s capital, and some members of the group hoped that by occupying 144 Piccadilly, they would give shelter to homeless families.

This indeed was the intent of schoolteacher Christian du Roche, who is described by the Daily Mirror as a schoolteacher, a father of two, and a ‘non hippie.’ It was his plan to use the building ‘to rehouse homeless families. But before he could move in his needy clients, the hippies took over.’ Du Roche, standing outside the mansion, remarked how ‘The hippies have spoiled everything we have hoped to achieve here.’

18 September 1969

And on the 18 September 1969, the Daily Mirror reports how ‘the Piccadilly hippies are under notice to quit their stately home,’ a high court judge ordering that 144 Piccadilly be handed back to the Amalgamated West End Development and Property Trust. But these hippies had other ideas.

Daily Mirror | 18 September 1969

On the same day, the Birmingham Daily Post is reporting how ‘there could be a bloody battle early next week at 144, Piccadilly,’ as Dr John had threatened to turn ‘the premises into a fortress’ in order to resist eviction. Indeed, it seems by the 18 September this barricading work was in full swing:

The barricading on the doors and windows was being reinforced and ‘Hell’s Angels’ stood by at the open window serving as a door, ready to pull up the improvised wooden ‘drawbridge,’ leaving no way of crossing the 20-foot deep basement area that serves as a moat.

Birmingham Daily Post | 18 September 1969

Not only was the mansion being barricaded; Dr John was preparing to use force. He commented to the press: ‘We shall use as much force and violence as is needed to stay in the building.’ Force and violence are not words usually associated with the peace-loving hippie movement – and it seems newspapers at the time took this as no empty threat.

20 September 1969

Two days later, the newspapers’ fears of violent clashes between hippies and police had seemingly come to fruition. The Aberdeen Evening Express reports how more than 60 police were sent to 144 Piccadilly ‘after a series of incidents:’

At one stage, plastic balls were thrown from the roof and windows of the house on to a crowd of about 200 people on the pavements below. In another incident, youths armed with wooden chair legs clashed with police. One of them was taken away. A girl, with blood streaming from a head wound, left in an ambulance. Earlier fire appliances were called when a small fire started on an upper floor. It was apparently put out by the hippies.

Chaos reigned; there were reports of petrol bombs being made, an eighteen-year-old boy fell through a skylight, a girl called Barbara was allegedly being held against her will, whilst pickax handles were allegedly being smuggled into the building.

But the hippies’ weapon of choice, according to the Newcastle Evening Chronicle, were brightly coloured balls used for boules:

Hippies, squatting in a mansion in Piccadilly, London, rained hundreds of brightly coloured plastic balls on onlookers today, injuring two policemen, as they prepared to repel attempts at eviction.

Newcastle Evening Chronicle | 20 September 1969

Newcastle Evening Chronicle | 20 September 1969

Dr John later denied that they had petrol bombs inside the building, although he reassuringly remarked that they ‘were pretty easy to make.’ Instead, he said they still had ‘thousands of plastic balls which were fairly effective at short range.’

The antics at the mansion brought crowds of onlookers to Piccadilly, and it soon became London’s hottest tourist attraction. Among the sightseers was a group of Manchester United football fans, who were in London to attend a match against Arsenal. With the football supporters added to the mix, ‘the situation became a little intense,’ with police trying to keep them away from the railing. However, ‘one or two of the red and white scarfed supporters did try to get inside the building [and] they were heard to say: ‘We could get them out.”

Hippie squatters on the balcony of 144 Piccadilly | Birmingham Daily Post | 20 September 1969

But ultimately, the next day, it was the police who swiftly ejected the hippie squatters – without the fight that was promised by Dr John, or feared by the newspapers. The Birmingham Daily Post labelled it the ‘three-minute bloodless battle of 144, Piccadilly.’ Police gained entry to the mansion by claiming that they needed access to help a pregnant woman who had gone into labour. But instead 200 officers soon swarmed the building, and the hippies were turfed out in three minutes.

23 and 24 September 1969

After the anticlimactic Battle of Piccadilly, which thankfully saw no injuries, the hippies moved on to a new building, namely the old National School on Endell Street, Holborn. The Reading Evening Post reports how the squatters ‘were still asleep as rush hour crowds made their way to work today.’

The same article contains an eyewitness account from a local cafe proprietor, who stated that ‘a rougher element of squatters had taken over the building since 144 Piccadilly closed:’

For the past two weeks the squatters have come in here. They have said please and thank you. But now I understand many of these have moved away because they do not want to be associated with the new squatters who have just moved in.

And these hippie squatters were prepared to defend their new home, like they had been at 144 Piccadilly. The group had a new spokesperson now, a seventeen-year-old girl named Denise, who according to the Birmingham Daily Post, said ‘they would stop any attempt by the police to get into the Endell Street commune.’

Denise Halloran | Birmingham Daily Post | 24 September 1969

The hippies were reported as ‘fortifying’ the old school, but the atmosphere on the 24th September was very different to how it had been days before in Piccadilly:

The carnival atmosphere of 144, Piccadilly, was not apparent in Endell Street. Most of the soot-blackened windows of the gaunt Victorian building were firmly shut. The barred mouth of an alleyway, was guarded by four tough looking men in their early thirties.

Allegedly seen at the window was a hippie armed with a knife, and once more the newspapers were fearful, seeing the Endell Street building as a ‘much more formidable’ building than 144 Piccadilly.

Aftermath

But again, ‘a short and overwhelming police operation’ managed to rid the hippie squatters, undertaken on the 25 September 1969. A day later, 58 people appeared at Clerkenwell Crown Court, charged with resisting the Sheriff of the County of Greater London in his attempts to evict them. During the hearing, one hippie interrupted proceedings by shouting ‘I don’t want your bail man.’

The cleanup of the occupied buildings began. Slogans (including ‘Death Before Employment’) had been left behind at the Endell Street school along with a ‘litter of personal belongings.’

Birmingham Daily Post | 27 September 1969

Meanwhile, the Birmingham Daily Post on 27 September 1969 reports on the array of fines and prison sentences given to ‘five Battle of Piccadilly hippies.’ Labourer John Charles Carroll was sentenced to three months’ imprisonment for possessing an offensive weapon – namely two studded armbands which he claimed he wore for ‘decoration,’ having ‘no intention of hurting anyone.’

Stagehand Justice Freeman, who lived at 144 Piccadilly, was sentenced to three months’ imprisonment, suspended, ‘for assaulting a police constable by throwing two plastic balls at him.’ The police constable in question said ‘one of the balls caught him on the thigh.’ Teresa Wynnyczenko, described as a Hell’s Angel, was also remanded in custody for having two plastic balls as ‘offensive weapons.’

Politicians, mainly Conservative ones, were quick to wade in. Enoch Powell, no stranger to controversy, is reported in The People as saying that the hippie squatters were out to ‘repudiate authority and destroy it.’ Fellow Tory MP John Biggs-Davidson, in the Reading Evening Post, commented how London had become a ‘notorious capital’ after being overrun ‘by hippies, anarchists and layabouts.’

Then leader of the opposition Edward Heath took a more balanced view, as reported in the Birmingham Daily Post:

He said hippies were a limited phenomenon. In every generation there was something of that kind but it should not be forgotten that there were millions of young people in Britain who were not following the hippy life.

Finally, what happened to the limited phenomenon of the London Street Commune? More buildings were sought and squatted in, and the process of squatting and eviction repeated itself. The Illustrated London News, in October 1969, reports how ‘Some dissidents are now trying to buy St Patrick’s Island, off the eastern coast of Ireland, for £20,000 and set up their own ‘republic.” However, St Patrick’s Island remains uninhibited, and is an important location for the breeding of seabirds.