Upon the advent of the First World War a new organisation was formed – the Women Police Volunteers. Later known as the Women’s Police Service, these women played a vital role in paving the way for the establishment and acceptance of women in the police.

Although the inclusion of women in the police was discussed prior to the outbreak of the war, and a small number of women were employed by forces such as the Metropolitan Police in limited roles, it was the Women’s Police Service that brought women police workers into the public eye, in a way that had never been seen before.

So in this special blog we will explore the birth of the Women’s Police Force, the role that these women played throughout the First World War, and the lasting legacy that these women created in the police force, all through the newspapers to be found on our Archive.

Want to learn more? Register now and explore The Archive

The Need for Women Police

Some months before the outbreak of the First World War, the need for women police constables was being discussed in the highest circles of the land.

The Leeds Mercury, 22 May 1914, reports on the latest discussions from the Criminal Justice Bill, undertaken at the House of Commons. Here:

Lord Henry Cavendish-Bentinck…moved a new clause providing that there should be appointed in every county borough and in every metropolitan borough, and by order of the Secretary of State in any other local authority, two or more women police constables, chosen in county boroughs by the Chief Constable and in London by the Chief Commissioner of Police.

Lord Cavendish-Bentinck explained how he wanted to see the employment of women constables ‘for the special purpose of reformatory and preventative work.’ They could, in his opinion, work in the ‘large towns’ of the country, protecting young women from the temptations of urban life, adopting a largely moral role which their male counterparts were unable to enact.

Giving examples of how women police constables were already employed in Germany, America and Canada, Lord Cavendish-Bentinck went on illustrate cases of where there were young child victims or witnesses involved, something he thought women constables could more valuably assist with:

When Depositions were made to male constables by young children, it was quite hopeless to get at the truth.

Votes for Women | 7 August 1914

A letter to Votes for Women in August 1914 from Bella Sidney Woolf outlines the desire for women police constables to be guardians of the innocent. Entitled ‘The Need for Women Police,’ Woolf describes a particularly disturbing incident where a ten-year-old girl was subjected to an indecent assault:

This incident speaks for itself. It is bad enough that a young child’s mind should be upset by such a frightful occurrence, but it is almost as bad that she should be expected to describe it to a man. It is surely here that a tactful and sympathetic woman is needed to help preserve the bloom of innocence and modesty that has received so rude a shock.

But back in May 1914, Lord Cavendish-Bentinck’s clause for women constables was withdrawn, owing to it being ‘foreign to the scope and purpose of the bill’ being discussed. However, with war looming not far away on the horizon, things were about to change for good.

Women and Children First

On 3 December 1914, the Sheffield Daily Telegraph pictures a member of ‘A new female police force, known as the Women’s Police Volunteers, in London.’

The Women Police Volunteers were founded in August 1914 by Nina Boyle and Margaret Damer Dawson, who gained the approval of the Commissioner of the Police of the Metropolis, Sir Edward Henry, for women groups of volunteers to be trained and to patrol the streets of London. In their roles, they could offer advice to women (Boyle and Dawson were concerned over the recruitment of vulnerable women into prostitution), with the Metropolitan Police there to assist them if necessary.

Their roles also saw them looking after children, as the Sheffield Daily Telegraph picture shows; the volunteer is shown ‘warning children of the danger of playing in the road.’

On the 10 December 1914 the Leeds Mercury pictures ‘Women Police Marching Single File in Hyde Park,’ remarking how the small corps, although ‘not large numerically…is exceedingly interesting’ and has provoked ‘keen interest’ throughout the country.

Women Police Marching in Hyde Park | Leeds Mercury | 10 December 1914

Meanwhile, in Hull, the Hull Watch Committee had appointed ‘four women-police to patrol the streets in the interests of girls associating with soldiers,’ as reports the Northampton Mercury in October 1914. Once more, women police were to be the moral saviours that male officers could not be. A moral panic was sweeping the country; soldiers filled cities, towns and villages in unprecedented numbers, offering new temptations to the women they now lived amongst.

By April 1915, ‘Women police [had] now become an established fact,’ as reports the The Suffragette. They could be found in Liverpool, Grantham, Sandgate (near Folkestone), Hull, Brighton, Croydon, Romford, Plymouth, Richmond and, of course, London.

In Grantham, where there was a nearby camp of ‘over 18,00 troops lying just outside, two policewomen have been stationed for many weeks past, and have been able to render valuable assistance to women and children.’ Again, these women were seen to be taking care of the moral welfare of the local community.

The Suffragette | 16 April 1915

The Suffragette goes on to describe a request of the Duchess of Portland, upon whose land near Mansfield a camp was situated. ‘Three policewoman’ had been engaged at her request, in order to enforce the ‘necessary regulations’ at the camp.

The same publication goes on to feature a letter from a ‘General Officer’ commanding troops ‘in one of the largest provincial towns,’ part of which runs as follows:

I understand that there is some idea of removing the two members of the Women Police Volunteers now stationed here. I trust that this is not the case. The services of the two ladies in question have proved of great value. They have removed sources of trouble to the troops in a manner that the military police could not attempt. I have no doubt whatever that the work of these two ladies is a great safeguard to the moral welfare of young girls in the town.

Official Recognition

In September 1916 the Leeds Mercury reports how:

Formed as a volunteer movement, the Women’s Police Service has now received official recognition from the Ministry of Munitions. The members are to police the big munition works of the country, and will be duly paid.

The Women Police Volunteers (WPV) had transitioned into the Women’s Police Service (WPS) a year previously, when founders Nina Boyle and Margaret Damer Dawson disagreed over the issue of a curfew being imposed on women of a so-called ‘loose character’ at the Grantham base, Boyle disagreeing and Dawson siding with the authorities. At a meeting of fifty women police all but two supported Dawson, and she took control of the organisation, renaming it the Women’s Police Service.

A ‘typical squad’ of the WPS | Leeds Mercury | 26 September 1916

Although the WPV continued its work in London and in Brighton, the WPS was to see far greater success, as evidenced by its recognition by the Ministry of Munitions.

Meanwhile, Margaret Damer Dawson became the undisputed figurehead of the WPS, offering a rallying cry in October 1916 at a meeting of the New Constitutional Society for Women’s Suffrage, which was reported in the pages of the Sheffield Daily Telegraph:

‘Hundreds of women are needed now as policewomen throughout the country, and they will be just as necessary when the war is over…It is not hard work,’ she explained, ‘and the walking, drilling and exercise are excellent for an ordinary healthy woman. As to the age for joining, we prefer women to be not under 25, and at the other end we use discretion. Any strong woman of 40 who would like to join this force I would welcome.’

The Sheffield Daily Telegraph goes on to outline the duties of the WPS:

They deal with the problems under the Criminal Law Amendment Act, the protection of children in parks, the supervision of the by-laws for strict trading, and the prevention of the excessive employment of child labour. In munition factories, where several thousands of women are employed, policewomen supervise the ‘clocking-in,’ they keep order as the women enter and have to be filed in queues, and they search women for contraband – a duty which cannot be performed by men. A great deal of patrolling is also done by them.

Indeed, the Home Secretary was ‘exceedingly favourable’ towards the WPS, as the Sheffield Daily Telegraph reports. He had ‘passed an Act which allowed local authorities to apply to the Treasury for the half-rate for women which they allowed to the police.’ Meanwhile, however, the Police Act still did not recognise that a police constable could be a woman as well as a man, and the women of the WPS were working hard to obtain a pension.

War Workers Honoured

There was no doubt that the WPS was a great success. In January 1916 the Dundee’s People Journal is reporting how it is ‘exercising a beneficial and quieting influence among the inhabitants of certain notoriously difficult districts.’ Furthermore:

It is…stated that they have made these districts safer for the ordinary passer-by, and have never been in any way themselves molested.

A training college had been set up by the WPS, ‘maintained entirely by voluntary contributions,’ which offered ‘an eight weeks’ course of training.’ Drill, first aid, practical instruction, the study of special acts relating specifically to women and children, and police court procedures all formed part of this course.

Dundee People’s Journal | 29 January 1916

By July 1917 Margaret Damer Dawson claimed that ‘since the war 560 women police had been officially recognised,’ as reported in the Bury Free Press. Furthermore, the only injuries they had received ‘during that time was one lost tooth and one black eye.’

Meanwhile in Birkenhead, March 1917, women police were ‘controlling the traffic points,’ as reports the Aberdeen Weekly Journal. In charge was Sergeant Phillis Lovell, ‘the only woman in the country to hold that rank.’

Phillis Lovell and Birkenhead’s women police | Aberdeen Weekly Journal | 23 March 1917

And these women’s efforts were to be recognised in the New Year Honours of 1918, where, as the Daily Mirror reports, ‘2,296 War Workers [were] Honoured.’ The Daily Mirror remarks on the remarkable cross-section of recipients – from photographers to town clerks, from hospital workers to journalists – and perhaps, most importantly for us, ‘Women Police.’

Awarded OBEs were Margaret Damer Dawson (Commandant of the Women’s Police Service), and her second in command, Mary Sophia Allen (Chief Superintendent of the Women’s Police Service).

The End of the War, the End of the WPS

After the First World War finally came to an end, the Weekly Dispatch (London) in November 1918 describes how ‘There is no doubt that there is an unsettled and anxious feeling among thousands of women whose work peace has brought to and end.’ Amongst those women were members of the WPS.

The article, penned by Lady Quill, relates how:

As for the Women’s Police Service, the Home Secretary has sanctioned the formation of a small body women patrols for London. One hundred women are to be enrolled for a beginning, and preference will be given to candidates who have had experience in similar work for the Government and or other forces. The pay will be 30s a week, with a war bonus of 12s, and provision will be made for a progressive rate of pay.

But this opportunity was not automatically offered to those women who had served in the WPS, Lady Quill writing:

This would seem to include women who have not been previously enrolled as policewomen, and, if this is so, the Women’s Police Service intends to protest on the ground that officers and members of the service who were pioneers should have the first chance.

Margaret Damer Dawson, as one can imagine, was full of protest at this perceived injustice:

These policewomen…have been trained by public moneys paid from the Treasury through the Ministry of Munitions. It seems, therefore, neither just nor economical that they should be set aside in preference to those who have had no training or experience.

Indeed, whilst women were accepted into the Metropolitan Police officially from 1919, the WPS was renamed the Women’s Auxiliary Service in 1920, and continued even as women were accepted into police forces around the country. But by the Second World War it had become all but defunct, and the Women’s Auxiliary Services became something of a catch-all term for all wartime services enacted by women.

And in 1920 Margaret Damer Dawson passed away, succeeded by her close friend and colleague Mary Sophia Allen. But whilst the WPS had less operational power, the trailblazing nature of the organisation cannot be ignored. It accustomed people across the country to seeing women in police uniform, and carrying out the word of the law. It paved the way for other pioneering women police officers, such as the first women officer Edith Smith (1915), first inspector Florence Mildred White (1930), first superintendent Dorothy Peto (1932), all the way up to the first woman Commissioner of Police of the Metropolis Cressida Dick (2017).

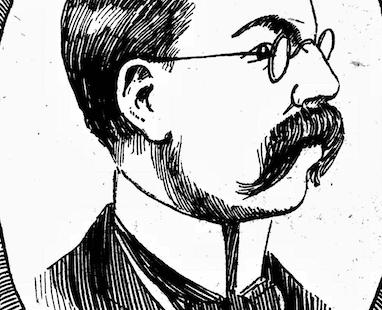

Mary Sophia Allen | Illustrated Police News | 12 June 1920

Furthermore, Dawson and the other volunteers were advocates, as well as pioneers. In response to the election of Lady Astor, the first woman M.P. to take her seat in Britain, Dawson is full of support, the Hull Daily Mail publishing her reaction:

I heartily congratulate Lady Astor on her election to the House of Commons. The large majority that she has gained shows that the time is now ripe for women generally to take their place in the government of the country. We look forward to the appointment of the first woman magistrate and the first woman judge.

We can only imagine how proud and delighted Dawson would have been to see the first women solicitors (who you can read about here), the first women judges and all those who achieved firsts within the police, and of course, to have seen every trailblazing woman who would later join the police, thanks in part to her legacy and the legacy of the WPS.

Discover more pioneering women whose stories we have found in our Archive here, or why not make your own discoveries in the pages of our collection? Begin your search here today.