In October 1947, actress Eileen Isabella Ronnie Gibson, also known as Gay Gibson, disappeared from the ship upon which she was travelling home from South Africa. Her disappearance, which later led to a murder trial, hit headlines across the globe, as the sensational case mirrored plots akin to those to be found in books authored by Agatha Christie.

In the first part of this special blog series, which you can read here, we took a look at who Gay Gibson was, and examined the hours and minutes leading up to her disappearance. In this second and final part, also using newspaper coverage from the time, we will investigate what happened after her disappearance.

We will look at how deck steward James Camb claimed responsibility for disposing of Gay Gibson’s body, and how he later went on trial, charged with her murder. We will also look at the enduring legacy of the sensational case, which took up newspaper columns across the world.

Gay Gibson is Missing

Some six hours after young actress Gay Gibson had last been sighted by the Durban Castle’s bosun, the alarm was raised that she was missing.

The Yorkshire Evening Post, reporting during James Camb’s trial on 18 March 1948, described how:

About 7.30 a stewardess went to Miss Gibson’s cabin. She noticed it was unlocked, which was unusual. She found the bed empty, but that it had been slept in, and that it was more disarranged than was usual after Miss Gibson had slept in it.

It was noticed that her ‘black frock,’ which she had worn during the previous evening, was ‘hanging on the wall.’ However, ‘her pyjamas and dressing gown were both missing.’ The alarm raised, the Durban Castle ‘retraced her course for an hour then after warning all ships to keep a lookout, she resumed her voyage.’

‘My Whereabouts at 3am’

It wasn’t long, however, before 30-year-old deck steward James Camb implicated himself in Gay Gibson’s disappearance.

According to nurse and stewardess Eileen Elizabeth Field, who gave evidence at the Southampton magistrates’ hearing into the disappearance and was tasked with looking after Gay’s cabin during the remaining part of the voyage, Camb told her that ‘Miss Gibson was supposed to be three months pregnant by a married man.’

The Yorkshire Evening Post reported how Eileen Field told Camb that such an allegation was a ‘rather serious thing to say.’ He doubled down, responding how ‘Miss Gibson had told him so herself.’

It was evident that Camb had spent some time with Gay Gibson. On 19 October 1947, a day after she disappeared, he handed a note to the Durban Castle’s captain Arthur Patey. The Yorkshire Evening Post reports how the note began: ‘‘With reference to your question of yesterday – i.e. my whereabouts at 3 am.’

In March 1948 the Yorkshire Evening Post would relate how this ‘written statement’ described how Camb had ‘made an appointment’ to meet Gay Gibson on 17 October 1947, and that ‘intimacy’ later took place between the two.

Evidence of Scratches

On 19 October 1947, on the same day that James Camb submitted his statement to Captain Patey, he was examined by ship’s doctor Anthony John Martin Griffiths. Griffiths would go on to give testimony at James Camb’s trial, which was reported on by the Essex Newsman on 19 March 1948.

The newspaper described how the doctor had ‘found on the right hand side of [Camb’s] neck several fine scratches about one inch long.’ Doctor Griffiths likened them to ‘those inflicted by cats’ paws,’ and thought they had occurred ‘in the past few days.’ Camb claimed that these scratches ‘were due to the use of a harsh towel.’

Doctor Griffiths, according to the Essex Newsman, found further marks on James Camb’s body. He located ‘between nine and twelve separate injuries on the right wrist,’ which he believed were ‘consistent with scratches caused by finger-nails…on the morning of October 18.’ Camb explained these scratches away too, describing how he had woken ‘up in the night two days previously with irritation and inflicted scratches’ on himself.

Without Gay Gibson’s body to examine, James Camb’s own body was the next best thing. By this point there was little doubt that the deck steward had caused her disappearance, but it was still to be determined whether or not he had caused Gay’s death, following an assault, or whether she had passed away naturally. The prosecution at his trial would use these scratches of evidence that he had attacked Gay Gibson, and how she had resisted him.

The Southampton Magistrates’ Hearing

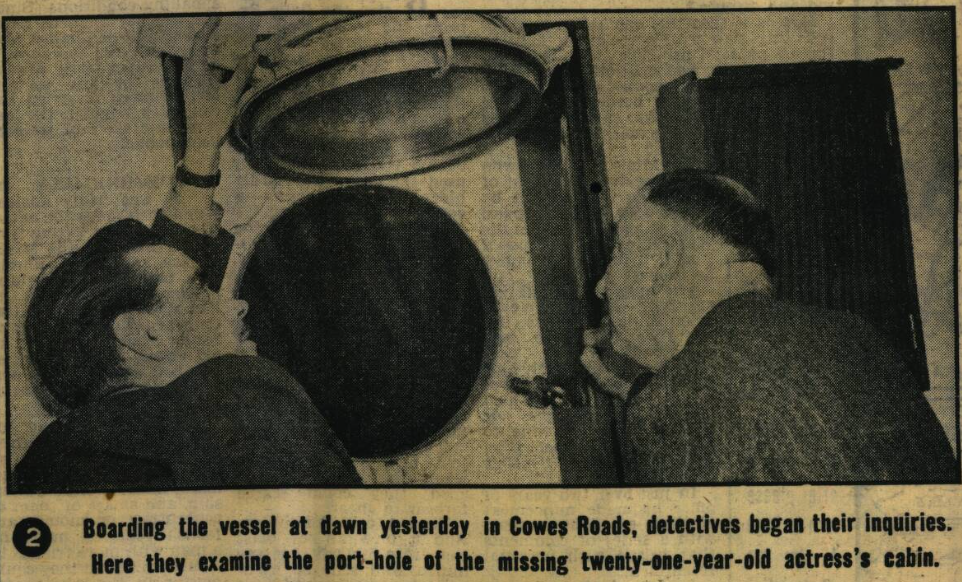

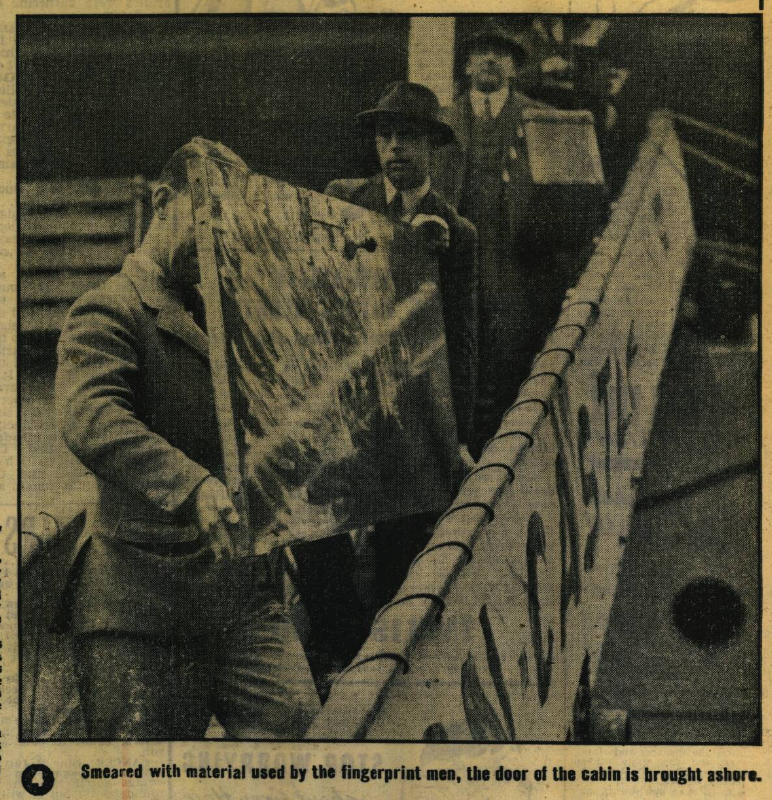

When the Durban Castle returned to port, investigations into Gay Gibson’s disappearance could start in earnest. The Sunday Pictorial on 26 October 1947 pictured detectives examining the porthole in Gay’s cabin, as well as the door of her cabin being brought ashore.

The initial hearing into Gay Gibson’s death begun in Southampton in late November 1947. The Daily Herald on 25 November 1947 reported how the accused, James Camb, took a ‘folded sheet of notepaper from his pocket’ and told the magistrates how:

‘I am not guilty…I did not kill Miss Gibson. She died in the way I described. My mistake was in trying to conceal what happened. Witnesses already called could, I am sure, have told much that would help in this case, and witnesses in South Africa know about the state of her health.’

The Daily Herald described how one of the witnesses at the hearing was Southampton-based Detective-Sergeant Quinlan. Quinlan interviewed Camb, cautioning him and having him sign his statement. Quinlan testified how Camb, upon being asked if he had anything to add to his statement, said:

‘What will happen about this? My wife must not hear about it. If she does I will do away with myself.’

Camb was indeed married, and had a young daughter at the time of his questioning. After being told that he would be charged for Gay Gibson’s murder, he stated: ‘My God, I did not think it would be as serious as that.’

Further testimony would come from Detective-Sergeant Quinlan’s colleague Detective-Constable Minden Plumley, to whom Camb allegedly testified how:

‘I have not had any sleep since it happened. I can’t understand why the officer on watch did not hear something. It was a hell of splash when she hit the water. She struggled. I had my hands around her neck, and when I was trying to pull them away she scratched me. I panicked and threw her out of the porthole.’

This alleged admission, which indicated that Camb had deliberately ended Gay Gibson’s life, would later be called into question when Minden Plumley resigned from the police force. But as for James Camb, he was ‘committed for trial at Hampshire Assizes.’

The Trial Begins

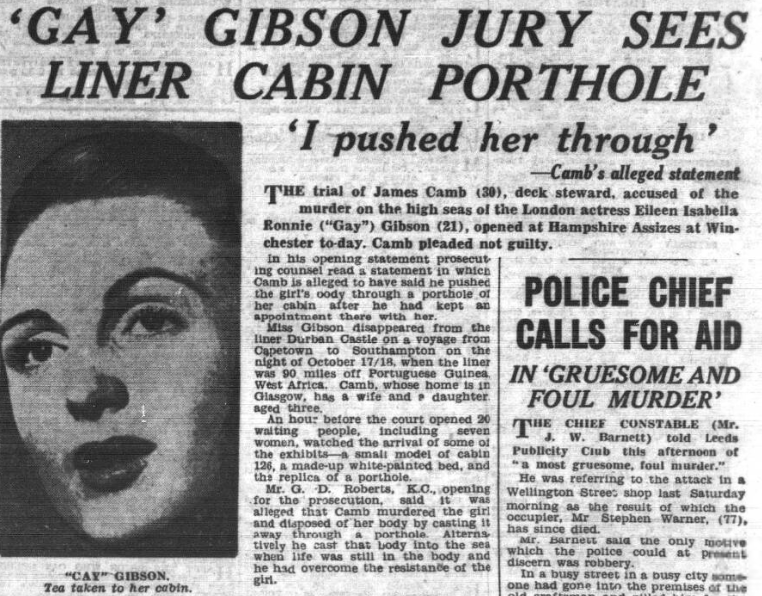

The trial of James Camb for the murder of Gay Gibson began on 18 March 1948 in Winchester. The Hartlepool Northern Daily Mail on the same day described the prosecution’s ‘long opening’ statement:

Mr. Roberts told how she [Gay Gibson] had embarked on the Durban Castle ‘apparently healthy, cheerful, and looking forward to continuing her theatrical career in Britain.’ He told of ‘very sinister incidents’ in Cabin 126, and how after the light had gone out ‘there was silence and peace.’

Also present in the court, according to the same newspaper piece, was ‘a large porthole,’ a morbid reminder of Gay Gibson’s fate.

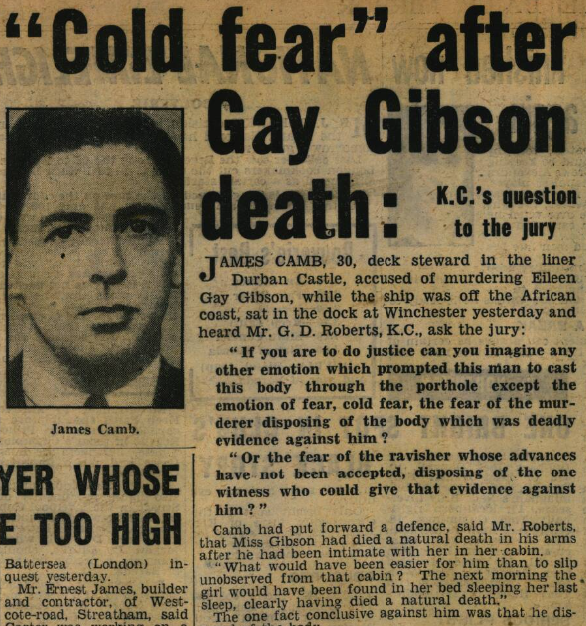

The Daily Mirror on 19 March 1948 contained more of Mr. Robert’s opening speech to the jury, which gives a sense of the direction that the prosecution would take in the case:

‘If you are to do justice can you imagine any other emotion which prompted this man to cast this body through the porthole except the emotion of fear, cold fear, the fear of the murderer disposing of the body which was deadly evidence against him? Or the fear of a ravisher whose advances have not been accepted, disposing of the one witness who could give evidence against him?’

Roberts cast doubt on Camb’s side of the story, that Gay had died from natural causes, and in a moment of panic had disposed of her body. The prosecutor continued:

‘What would have been easier for him than to slip unobserved from that cabin? The next morning the girl would have been found in her bed sleeping her last sleep, clearly having died a natural death.’

It was then stated to the court how ‘the one fact conclusive against [Camb] was that he disposed of the body.’

The Case for the Defence

James Camb took to the witness box in his own defence on 20 March 1948. The Sunday Pictorial described how the 31-year-old deck steward stated how that he was ‘ashamed,’ whilst decrying his ‘beastly conduct.’

The defence’s tack was clear. First, they sought to cast doubt on both Gay Gibson’s character and health, using witnesses such as Mike Abel. Abel’s testimony painted Gay as tempestuous and sickly all at the same time, all at once a red-blooded temptress and a delicate lady who could faint due to the slightest upset. Both these factors could excuse Camb, providing a reason as to why he was in Gay’s cabin, and why she passed away unexpectedly.

The closing speech of defence barrister J.D. Casswell, as reported by the Hartlepool Northern Daily Mail on 22 March 1948, attempted to dissuade the jury that Gay was anything but an unwilling participant in her encounter with James Camb:

In an 85-minute closing speech, Mr. J. D. Casswell, K.C., leading for the defence, asked the jury a series of questions, including: ‘Was there anything to prevent this girl calling out and preventing this man from coming into the cabin’ and ‘Don’t you think she must have known why he came, and, if she did, why resist?’

The defence also called forensics expert Professor J.M. Webster, of the West Midland Forensic Science Laboratory, to the stand. He believed Camb’s account of a natural death to be a true one, as he stated:

’She was dead, in my opinion, before she was put in the water. Camb’s account, in my experience, fits in with medical science.’

He pointed to other evidence given, such as the grey colour of Gay’s fingernails, and her ‘tendency to fainting,’ as being symptoms of ‘heart trouble.’

It was back, then, to the prosecution barrister to sum up, and he did so as follows:

‘There was no doubt that the woman was dead before she was put through the porthole. The issue was: is it proved that the girl met her death in that cabin in such circumstances that the prisoner could be convicted of murder? Several other matters had been raised in the case. Was she pregnant, was she a woman of loose morals, had she heart disease which nobody could diagnose, and had she asthma? The jury were not called upon to answer questions of that kind. They had to decide, if it was proved that the death of the girl had been caused in such circumstances, that the prisoner was guilty of murder.’

The Verdict

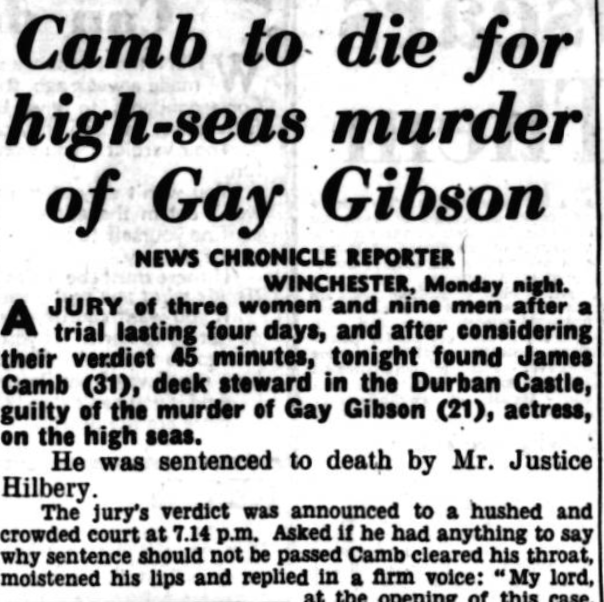

James Camb did not have to wait long to hear the verdict. The Daily News reported on 23 March 1948 how:

A jury of three women and nine men after a trial lasting four days, and after considering their verdict 45 minutes, tonight found James Camb (31), deck steward in the Durban Castle, guilty of the murder of Gay Gibson (21), actress, on the high seas.

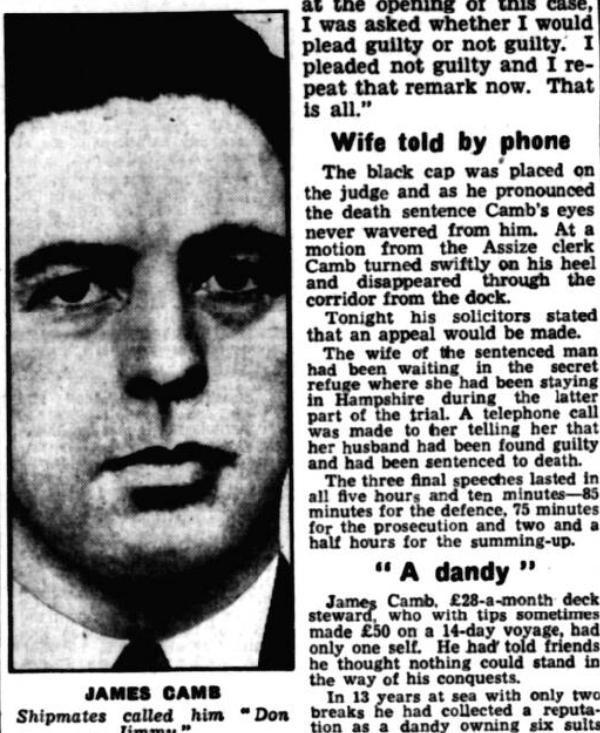

The verdict was announced at precisely 7.14pm to a ‘hushed and crowded court.’ Camb, now a convicted murderer, was asked if he had anything to say. He replied, according to the Daily News, in a ‘firm voice,’ telling the judge:

‘My lord, at the opening of this case, I was asked whether I would plead guilty or not guilty. I replied not guilty and I repeat that remark now. That is all.’

Such words were in vain, as Mr. Justice Hilbery, who presided over the trial, donned his dreaded black cap and ‘pronounced the death sentence.’

The Daily News then chose to highlight Camb’s womanising ways. Born in Lancashire, with a background in both the Merchant Navy and the Royal Australian Navy, Camb:

…£28-a-month deck steward, who with tips sometimes made £50 on a 14-day voyage, had only one self. He had told friends he thought nothing could stand in the way of his conquests. In 13 years at sea with only two breaks he had collected a reputation as a dandy owning six suits at a time, bright ties, and a store of light conversation for the passengers.

James Camb, however, was not destined to die via the hangman’s noose. On 30 April 1948 the Halifax Evening Courier reported how:

The Home Secretary has recommended a reprieve for James Camb ship’s steward, sentenced to death at Winchester, on March 22, for the murder on the high seas of actress, ‘Gay’ Gibson.

The Man Who Nearly Hanged for Murder

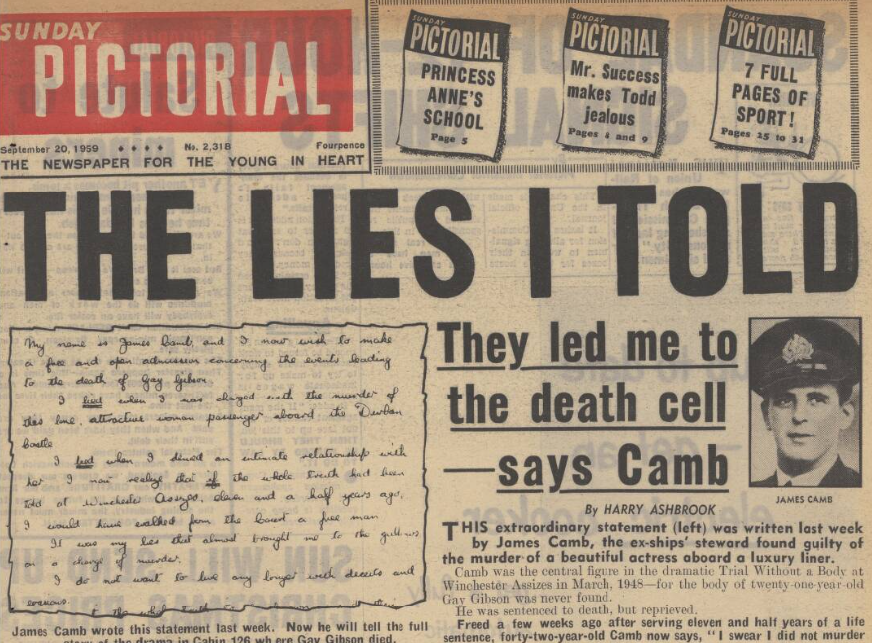

Nearly a decade later, James Camb was released on license from prison. Given the sensational nature of the case, which he was quick to capitalise on, Camb told his version of the disappearance of Gay Gibson to national paper the Sunday Pictorial. The 4 October 1959 piece ran with the headline ‘The Man Who Nearly Hanged for Murder Tells His Own Terrifying and Dramatic Story of the – Panic Porthole.’

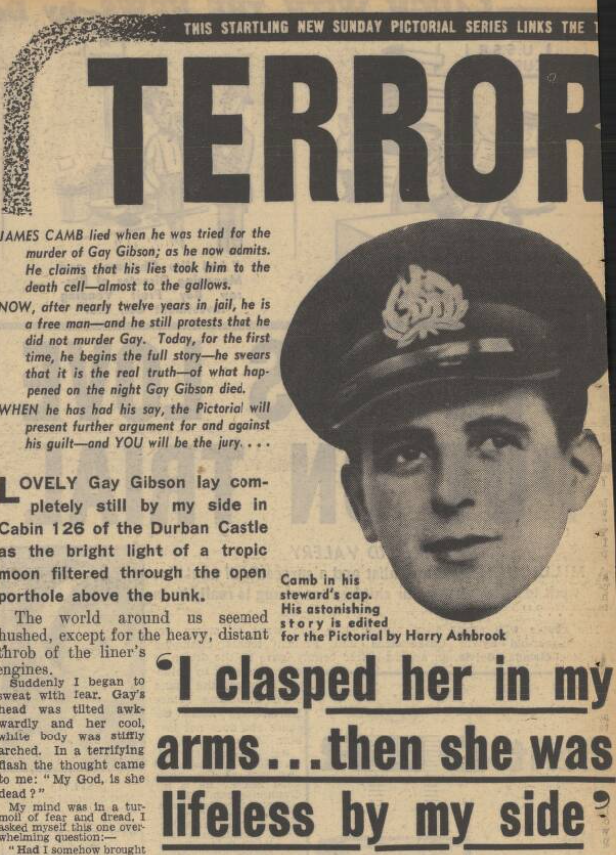

Despite promising to provide the ‘real truth,’ the piece, which was edited by Harry Ashbrook, shed no real light on the events in Cabin 126. Instead, it provided almost a soft-porn glimpse of Gay Gibson lying in James Camb’s arms ‘as the moonlight flooded through the open porthole.’ Camb describes how Gibson passed away as they were together in her bunk, and his subsequent panic. He tells of his confusion of how the bells came to be sounded, when at this point, so he says, Gay was already dead. He comes to the conclusion that he must have pressed against them in his blind panic.

In his own words, Camb says:

I felt truly and deeply sorry for this woman who had walked so tragically into my life. But I realised that there was little more I could do. My mind was poisoned by unknown fears. I stood over her dead body. A cool breeze wafted in from the open porthole. At that moment, I saw the porthole as my only escape. I was prepared to take the chance that I had not been recognised by the night watchman…saying to myself: ‘I’ve got to get rid of her body. I’ve got to get rid of her body. It’s my only chance.‘

And so he pushed Gay’s body through the porthole, ending the piece with a dramatic flourish, in direct opposition to his alleged statement to Detective-Constable Minden Plumley:

THERE WAS NO SPLASH AS HER BODY HIT THE WATER.

As well as adding little to his initial statements, this piece is remarkably self-centred. Camb is concerned with his panic, what will happen to him, if the body of Gay were to be discovered. There is no thought of Gay Gibson, her family, nor the dignity, whether or not she had died a natural death, of which she and her body were deserving. It is a difficult read.

Endings and Legacy

Although James Camb was released in 1959, the Daily Mirror reports in May 1971 how the ‘convicted killer of actress Gay Gibson’ was ‘sent back to jail…to continue his life sentence.’ He had been sentenced following a series of sex offences ‘against three young schoolgirls at a hotel in Roxburghshire, where he worked as a head waiter.’

Camb was released in 1978, and passed away a year later. Meanwhile, Gay Gibson’s body was never found, although the story of her death still permeated popular culture years later. The case was the subject of a book authored by Denis Herbstein, who wrote to theatre magazine The Stage in January 1987 asking anyone who might have known Gay to get in touch with him. Meanwhile, Susan Clarke for the Birmingham Weekly Mercury in October 1991 used Gay Gibson’s case as an example for how ‘sex could be the death of you,’ echoing the sensationalism of some half a century before.

The difficulty of such a sensational case is how the victim at the centre of it, Gay Gibson, can be obscured. Although her life was dissected, poured over, in court, not even her body remained for her to tell her own story. At the age of only 21, she had her whole life ahead of her, and who knows what she could have achieved, whether or not her life was snuffed out by James Camb.

Find out more about Gay Gibson, the history of crime, and much more besides, in the pages of our newspaper Archive today.