In this very special blog, Jessie O’Hara, from our sister site Findmypast, takes a fascinating look at astrology through the pages of our newspapers. Featuring articles all the way from the eighteenth century to the twentieth century, she traces the development of attitudes towards astrology across three centuries, from scepticism to horoscopes being a mainstay of mainstream media.

Register with us today and see what stories you can discover

Believer or non-believer, agnostic or sceptic, there is no denying that astrology as a (pseudo)science, art form, divination tool and a symbolic language has been pervasive across cultures for thousands of years. In its most basic form, astrology draws information about human affairs and relationships as well as terrestrial events from the position of celestial objects in the sky.

Almost all civilisations across the globe have attached cultural significance to the movement of the stars and luminaries; indeed, tropical astrology – the astrology used most commonly in the West – dates as far back as the 18th century BCE. It is by far not the only form of celestial divination, of course – Vedic (Hindu) astrology, Chinese astrology, Ancient Egyptian astrology and more have all coexisted and informed one another since before the Common Era. Vedic astrology, for example, uses terms derived from Ancient Greece; horoscopic astrology was created combining the work of the Ancient Egyptians and the Babylonians. What we now consider modern astrology – that is to say, astrology as it pertains to horoscopes and star signs – is a derivative of its tropical form, and began to make a resurgence in the mid 1900s after its dismissal from scientific circles during the Enlightenment.

We can almost see this scholarly downfall as it occurs through our newspaper archive. One of the earliest mentions of astrology is in 1761, in the Chester Courant, taking the form of an advert for one Solomon Gibson, ‘Professor of Astrology’.

It is around this time that the separation of astrology and astronomy began to become more apparent – Solomon Gibson would have been one of only a few astrology professors still practicing. In another instance, seven years later, a highly regarded female astrologer is offered a large sum of money from a family member to give the profession up.

She refused, stating she could make ‘five times’ the amount working as an astrologer – but considering the large sum on offer, it is easy to understand that the field was beginning to face derision and was not deemed worthy of professional or social acclaim.

As if to confirm this, the Leeds Intelligencer reported in 1789 that:

As fortune telling is a very flagrant imposition on the sense and understanding of rational beings, the following short story may be of use to undeceive those who are infatuated with that passion, and also serve to divert those who heartily despise all such chimerical notions.

The story that follows tells the slightly gruesome tale of Leopold the Third, being told by his astrologer that he should die on the third day of the week; the Prince proceeded to order his execution by hanging for foretelling such an event. Though the astrologer narrowly escaped his execution with flimsy excuses as to his prophecy, the story ends with the macabre line:

Leopold lived to see the conjurer drowned as he was crossing a lake in a small boat.

Indeed, despite the ancient roots of such a practice, there is no doubt that it has been used for extortion throughout the years. In one particularly sad story, the London Courier and Evening Gazette reported on a lonely, unmarried woman attending an astrologer in order to see if ‘the fates had ordained her to a life of celibacy’. To the astrologer’s credit, he announced that Mars and Venus were conjunct, suggesting that she was destined to marry, and that the ‘malignant influence of Saturn’ had indeed caused her loneliness – both of which, in astrological terms, would be considered fair assertions. Had the astrologer ended there, perhaps he would not have been so forcefully apprehended.

He then proceeded to give specific details on the man she is set to marry, and went so far as to give her designated lottery numbers. Of course, the lottery numbers turned out to be false, and the man was prosecuted.

The few fortune tellers and astrologers remaining continued to sell their services, but to little applause; in 1777, an extract from a book titled The History of Great Britain was published in the Caledonian Mercury. It begins:

None of the mathematical sciences was cultivated with such diligence, in this period, as the salacious one of judicial astrology. None, indeed, were honoured with the name of mathematicians but astrologers, who were believed by many to possess the secret of reading the fates of kingdoms, the events of war, and the fortunes of particular persons, in the fates of the heavens.

Despite the fairly positive start, the extract continues to tell the tale of 1186, when a planetary conjunction in the sign of Libra was predicted to cause such horrific storms that would sweep away entire towns and cities, causing mass panic across the population. The article continues:

But, to the utter confusion of the poor astrologers, the 16th of September was uncommonly serene and calm, the whole season remarkably mild and healthy, and there were no storms all year.

The author then proceeds to term astrology a deceitful practice – though not without merit. Indeed, he concludes by crediting astrology for the progressive work being completed in astronomy at the time, claiming ‘there is the clearest evidence that the astrologers of this period could calculate eclipses, could find the situation of the planets, and knew the times in which they performed their revolutions.’

As the years go by, astrology begins to fall further and further from favour, and by 1850, there is little mention of the practice unaccompanied with disdain.

The Taunton Courier and Western Advertiser went so far as to claim:

We find them, like the ancient Chaldeans and Egyptians, under the denomination of a hierarchy of astronomers and astrologers, studying the heavens as a Bible, grouping the stars in imaginary forms, converting them into religious and allegorical myths, watching the revolutions of the planetary bodies to cast horoscopes with greater accuracy; accumulating facts and gaining knowledge, but converting all the knowledge thus acquired to profit of their own order.

The tone used when discussing astrology becomes increasingly cynical as time goes on and its dismissal from academics is more widely accepted: the general view throughout the 1800s seems to be that astrology was, at its core, exploitative.

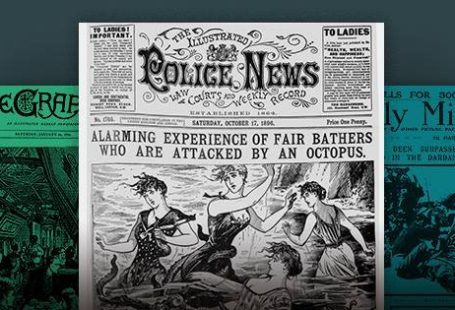

But of course, without an inescapable social fascination even despite these views, we wouldn’t see the prevalence of horoscopes that we do today. Short stories and fiction features beyond the 1850s often made mention of astrology.

The trajectory of the cultural interest in astrology seems to have moved from derision to a certain compulsion for the fantastical; as seen above, astrologers themselves became less of an object for ridicule, and instead magical (if non-existent) beings and sorcerers. Chapter 37 of the featured story above begins:

Ere the next day was over, it was understood throughout the castle that Lord Herbert was constructing a horoscope – not that there were many in the palace who understood what a horoscope really was, or had any knowledge of the modes of that astrology in whose results they firmly believed; yet Kaltoff having been seen carrying several mysterious-looking instruments to the top of the library tower, the word was presently in everybody’s mouth.

In another instance, one of the four pages of literature published in Ben Brierley’s Journal in 1882 features a light-hearted, playful conversation between an astrologer and her subject.

It’s clear that as time passed after the astrological fall from grace, interest began to pique again – less academically, as it was prior to the Enlightenment, and more simply in wonder of the mystery behind space and the stars.

This interest also stretched into other cultures. There was a certain allure to traditions that still factored astrology into the everyday in a way that the British culture, or the West more generally, had forgotten.

The Illustrated Times, for example, reported on how Chinese weddings employed both mystical matchmakers and judicial astrologers to report on the horoscopes of the intended couple. The circumstance and date of the wedding could then be postponed for significant periods of time, depending on when the stars deemed it most appropriate and most fortunate for the union to occur. This is similarly noted in the Ipswich Advertiser in 1858:

A lucky day for the [Chinese] marriage rites is considered important. On this point, recourse is had to astrology, and the horoscopes of the parties are diligently compared.

The Methodist Times discusses Ceylonian astrology with slightly more judgement:

It has been rightly said that the true Tun Sarana (Three Refuges) of the Buddhists in Ceylon are astrology, charms and devil-dancing. It is true that the intelligent Buddhist condemns the last of these (though not always in practice), but the belief in astrology and charms seems to be universal.

In a similar vein, the Globe reported on the ceremonial use of natal charts for baby boys born into Hindu culture in 1896.

The interest in astrology then seems to not only be roused because of its mystical roots, but potentially also as a route to understanding different cultures across the world – particularly in areas recently colonised by the British. Perhaps, then, this is where we see astrology take the form of a symbolic language; as pervasive as it is throughout historical cultures, astrology then becomes as widely spoken a language as any other, and an avenue by which to make different cultural practices more accessible and understandable to the general British public.

It is in the late 1800s, going into the 1900s, that we begin to see Western astrology re-emerge from the shadows, potentially due to this wider cultural intrigue. In 1890, the Pearson’s Weekly published an incredible hand-drawn natal chart of an infant, who won the astrological reading as a prize.

The astrologer has used the child’s birth date, birth time, and place of birth to determine where each constellation and planet lies across the twelve houses of tropical astrology. From the left to right, we can distinguish the houses noted in Roman numerals, with the zodiac symbols accompanying their relevant sector; Scorpio for example lies in the first house of the ascendant, and Taurus in the sixth. The astrologer even went so far as to note the degrees at which each planet was conjunct with one another – a remarkable feat of astronomical knowledge and prowess, if nothing else.

This intrigue then starts being applied to figures of greater significance. In 1893, the recently married Princess May and the Duke of York – soon to be the King and Queen of the United Kingdom – had their horoscopes reported on in the ‘Gossip of the Day’ column of the Yorkshire Evening Post.

The article asserts that the Duke of York ought to become a believer in astrology, as prophecies of his reign had begun to come true. Perhaps again, this is another example of astrology allowing previously inaccessible characters to become more relatable for the wider masses.

Moving further into the 1900s, astrology comes round full circle once again, with multiple news sources and academics beginning to distinguish it as a solidified, and rational, form of science.

Advertisements of professional astrology readings and scholarly astrological texts begin to appear more commonly than ever before.

This seems to align with an increase in patriotism during wartime years. The Illustrated London News reported on the discovery of Queen Elizabeth I’s astrological planisphere in 1923.

The planisphere was made out of metal, engraved with the arms of Elizabeth, and then further divided into the twelve astrological houses. It had notations for each of the months and symbols of the zodiac, with Latin terms denoting the meaning behind each house and sign. Around 13 inches in diameter, it was designed specifically for Queen Elizabeth I by her Royal Astrologer. Interestingly, it is reported that not only did she consult with her astrologer throughout the entirety of her reign, but she may have also had an illicit affair with him – and as such, astrology becomes less of an academic field of science and more a source of social and cultural gossip.

This revival continues into the 1930s, and even sees astrological conferences held across the country.

More and more, we see professional astrologers once again take the stage, offering natal chart predictions and other forms of individual divination.

Of course, history repeats itself; as we recognised earlier, the common interest in such a pseudoscience allows for the exploitation of wealthier parties. In 1937, The Scotsman reported on the fraudulent actions of a woman under the name of Blanchet, who under the guise of being a fortune teller, swindled £10,000 from one of her clients.

Coming into the years of the Second World War, scepticism grows not only of astrology itself, but its use when applied to the events of the war. Indeed, this isn’t a new phenomenon – astrology has been used in attempts to predict the outcomes of wider terrestrial events for centuries prior to this. But modern cynicism, combined with a general national unease and more accessible media, led to articles like ‘The “Science” of Astrology and its Application to War’, published in The Sphere in 1942.

In the article, the author refers not only to one specific newspaper astrologer prevalent at the time – though he remains unnamed – but also to the evolution of newspaper astrology from ‘originally concentrat[ing] on birth dates and prognostications of individual readers’ futures’ into ‘the uninvited job of making general predictions about the future course of the war’. He continues:

Primarily, it is these general predictions which are the subject of my criticisms. Certain astrologers in the past nine months have indicated that there would be no more mass raids on this country. Nearly all of them predicted that something terrible would happen to Hitler in May and June this year, with the result that actual hostilities were sure to be over by August or September, when mopping-up operations would be in progress.

We can see, then, how the same ethical debates that led to the derision of astrology in the late 1700s begin to arise once again. Its use for personal exploitation, as well as to cause extreme emotion across wider circles surrounding contemporary events, was highly criticised; just as the Caledonian Mercury exposed astrology for causing false panic in 1777, we see papers of the 1940s criticising the practice for giving false hope.

This brings us into the horoscopic astrology we see most commonly today. The practice began to take its more individualistic form once again, and even had companies such as Pimm’s using it as a form of advertisement, bringing humour to the forefront with playful taunts in the 1950s.

Cleverly, each advertisement for this whimsical advertising campaign corresponded to each of the months of the zodiac.

These adverts are particularly reminiscent of the astrology we see today: individual horoscopes based around the sun sign, featured as a fun addition to a newspaper or magazine.

Though we see these from the 1960s onwards, they became particularly prevalent beyond the 1980s, and shape what we see astrology as today: a pseudoscience, yes, but a light-hearted one.

It is clear beyond all else that astrology has had both its supporters and its naysayers over the centuries – it has journeyed through repeating peaks and troughs of popularity, and as with any developing practice or science, ethical concerns surrounding exploitation and mass influence come to the fore when considering the effects of its mass prevalence. Nonetheless, the astrology we know now is a much smaller derivative of what it once was. Perhaps more than anything, it is important to recognise that without the cultural belief in astrology passed down centuries prior, we would not see the advancements in scientific astronomy and the study of space that we do today.