In the aftermath of the First World War, severe competition for jobs, especially in the ports of the United Kingdom, became widespread. Alongside this competition, a new awareness of Britain’s Black and minority ethnic population arose, fuelling the perception that such so-called ‘foreigners’ were stealing the scarcely available jobs.

This toxic atmosphere would ultimately lead to the race riots of 1919, which began in January and lasted until August of that year. Violence broke out in cities across the United Kingdom, between white and minority groups, leading to several deaths and many injuries.

And in this special blog, we will try to understand the race riots of 1919, which represented a grim period in the history of race relations in Britain. Using our newspapers, we will look at how the press responded to the violence in the direct aftermath of the disturbances.

Please do be aware, that the language used in the newspapers of the time is outmoded, and offensive today. Replication of such language has been minimised as far as possible in this blog.

Register with us today and see what stories you can discover

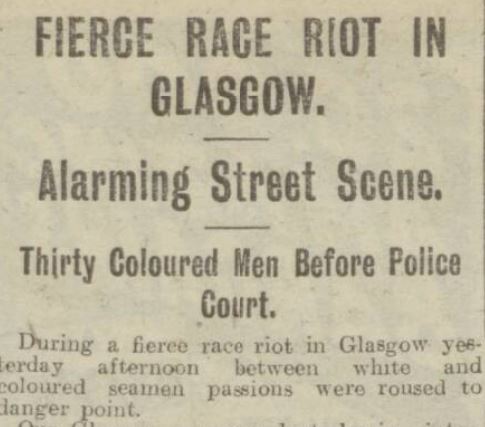

‘Fierce Race Riot in Glasgow’

One of the first outbreaks of racially motivated violence was witnessed in Glasgow, in the January of 1919. The Dundee Evening Telegraph on 24 January 1919 reported on a ‘Fierce Race Riot’ in the city, which had witnessed an ‘alarming street scene’ during the course of the disturbances.

The Glasgow correspondent for the newspaper outlined why the violence had broken out. It was over competition for work, as it was perceived that Black sailors were ‘being given the preference in signing on for a ship about to sail.’ This was resented amongst the white sailors. Meanwhile, the perception that Black sailors would ‘accept lower wages’ also further inflamed the situation, which resulted in a ‘scuffle… in a court adjoining the Mercantile Marine Office, where seamen sign on.’

The Dundee Evening Telegraph then describes how a Black sailor ‘fired a revolver,’ injuring a white seamen from Glasgow in the neck. This incensed the crowd even further; with the white contingent ‘charging’ at the Black seaman, the latter group taking ‘refuge in a close leading to a lodging-house’ where they lived.

The white mob were armed, according to the same newspaper report, some with revolvers, and others with bottles and stones. These were thrown at the retreating Black sailors, and also at the windows of the lodging-house.

But when the police arrived on the scene, they arrested ‘all of’ the Black seamen, who ‘offered no opposition.’ Thirty Black men were then remanded at the Central Police Court in Glasgow. The newspaper does not detail if any of the white contingent were arrested, and if they were not, it is a startling example of the inequality faced by the Black population in Britain at this time.

These race riots in Glasgow had resulted in injuries to three men, but thankfully there were no fatalities. This, however, would not be in the case in Liverpool some months later.

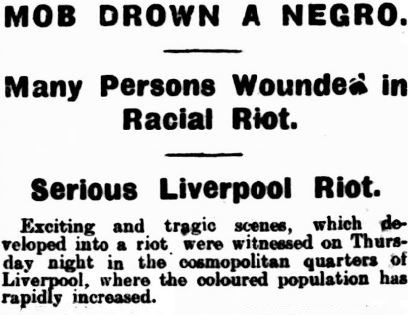

‘Fatal Liverpool Battle’

Several months later, on 6 June 1919, the Daily News (London) reported on another ‘Race Riot,’ which had occurred, this time, in Liverpool. The newspaper relates how prior to this outbreak of violence, ‘racial feeling’ had been running ‘high for some time past.’ Such tension had resulted in a ‘fatal battle’ between some of Liverpool’s Black population and some ‘Russians and Swedes, in the Old-George’s-square quarter.’

Most shocking of all, the violence between these groups led to a Black man being ‘thrown into the dock and drowned.’ Fourteen others were injured, as the Daily News (London) relates, with five policeman and nine civilians sustaining injuries.

What is disturbing about this report is its brevity. Consisting of only a few paragraphs, the death of the individual who was thrown into the dock is not enlarged upon, instead, the newspaper goes on to relate how ‘the fight raged for about an hour’ and was attended by 40 police officers, who were at ‘first overpowered’ by the crowd.

The Newcastle Daily Chronicle on 7 June 1919 also reported on the ‘Serious Liverpool Riot,’ leading with the headline of ‘Mob Drown a Negro.’ The newspaper referred to the ‘exciting and tragic’ scenes in city, which had broken out in ‘the cosmopolitan quarters of Liverpool,’ where the minority ethnic ‘population [had] rapidly increased.’

This report in the Newcastle Daily Chronicle outlined how the violence begun with a Black group of men ‘attacking and stabbing a number of Danes.’ Note the difference between the reports here: the Daily News (London) has Russians and Swedes involved in the affray, whilst the Newcastle Daily Chronicle puts Danes there. But neither paper give a reason for why exactly the violence started, offering the increase in the Black population and interracial tensions only as possible explanations.

And the violence here was devastating. A police constable named Brown was shot in the mouth, ‘the bullet passing through his neck and wounding a sergeant.’ Another police constable was ‘slashed with a razor.’ Finally, one of the Black persons ‘engaged in the affair was taken from the police by the mob, thrown into the Queen’s Dock, and drowned,’ in scenes that were horribly reminiscent of those witnessed in the southern states of America at the time. And according to the Daily News (London), they were only ended when the police were reinforced by ‘civilians and discharged soldiers.’

But like the aftermath witnessed in Glasgow, the Newcastle Daily Chronicle narrates how it was thirteen Black men ‘who were charged with having attempted to murder three police officers and with having riotously assembled.’ The men, most of whom were bandaged, were remanded at Liverpool Police Court.

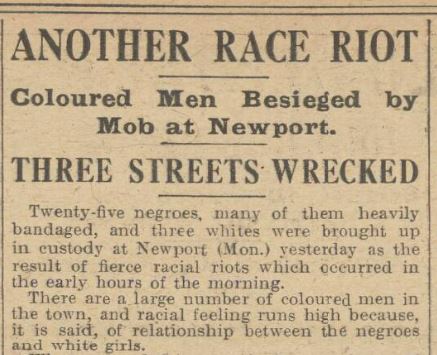

‘Besieged By Mob at Newport’

The spark of racially motivated violence had been lit, and its impact was soon witnessed across the country. On 8 June 1919 national newspaper the Sunday Pictorial reported on ‘fierce racial riots’ in Newport, Wales. Again fuelled by increasing racial tensions, and the increase of the Black population in the town, it was reported that the outbreak of violence had been fuelled due to relationships between Black men and ‘the white girls.’

The Sunday Pictorial related how:

The affray started on Friday night with an altercation, in which blows were struck. A large crowd gathered and the negroes retreated to two houses where they live in George-street. Later the coloured men ventured out, and this was the signal for the renewal of the fight. A revolver was fired, and when a number of negroes armed with sticks, pokers, etc., appeared the riot became general.

‘A baton charge’ was then made by the police, but it was too late to stop the damage to three streets in Newport. The article describes how:

All the windows were smashed, the houses were forced, and all the furniture smashed to atoms. Chinese, Greek and other foreign boarding houses were attacked.

Furthermore, the Sheffield Independent on 14 June 1919 reported how furniture ‘was burnt in the streets of Newport,’ with shops and restaurants also being ‘wrecked.’

The Montrose, Arbroath and Brechin Review later reported, on 20 June 1919, how the police ‘effected thirty arrests,’ following the ‘wild scenes’ at Newport. One of the arrested men, who was remanded in custody for one week, as details the Sunday Pictorial, implored:

Why do you keep us here? […] We have businesses to look after, and we ought to get our rights in Great Britain the same as everyone else.

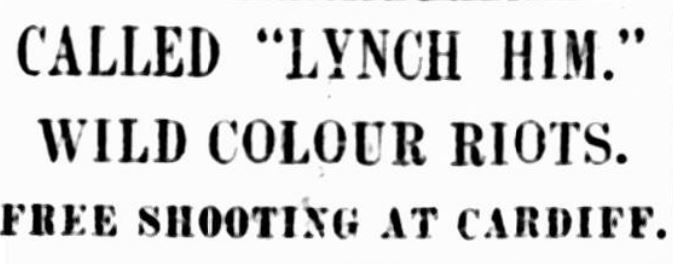

‘Free Shooting in Cardiff’

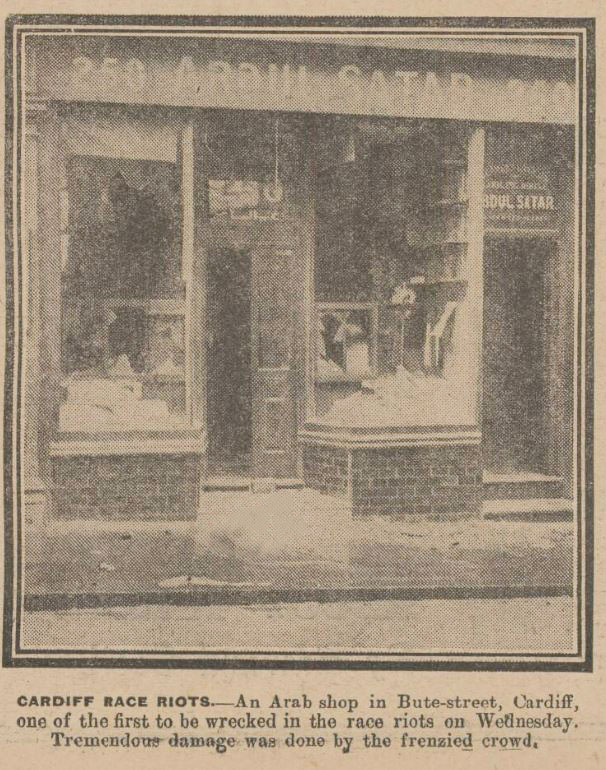

Meanwhile, the violence spread further down the Welsh coast to Cardiff, the city witnessing ‘wild colour riots,’ as detailed by the Belfast Telegraph on 13 June 1919. Again, ‘familiarity between white women’ and Black men was identified as the cause of the ‘race riot,’ which had broken out in Bute Town, one of Britain’s most multicultural areas at the time.

The Belfast Telegraph, drawing on a report from national newspaper the Daily Express, describes how the violence started when a Black man began ‘firing on the police.’ This then ‘infuriated’ the white members of the crowd, ‘who attacked the negroes and hunted them for hours.’ ‘Free shooting’ was then witnessed in the Welsh city, with ‘volleys’ being ‘fired in the street and from houses.’

The reporter from the Daily Express detailed how as the day went on, the ‘trouble…assumed a fiercer aspect.’ This was apparently fuelled by the sight of Black man walking down Bute Street ‘arm-in-arm with a white woman.’ Then, the rumour was put around that five Black men were ‘in a house in Millicent Street,’ where ‘hundreds of people assembled.’

Millicent Street then became the locus of the violence, as the Globe also reported on 13 June 1919. The Globe tells of how the area had a high Somalian population, and how the assembly of the mob on that particular street ended in tragedy.

The Globe reports that the house on Millicent Street was allegedly home to ‘a man of colour,’ who was said to have ‘threatened a woman.’ The house was entered by the mob, and then:

The inmates, in a state of panic, commenced shooting, and the mob retaliated with stones and ginger beer bottles. John Donovan, aged 47, a discharged soldier, wearing the Mons ribbon, was shot through the heart and he died after removal to hospital.

Only then did the police intervene, the Globe describing how:

The police came up and entered the house, one receiving a shot through the helmet and another a bullet through his cape, while others sustained slight injuries from stones. They arrested the occupants, one of whom, in the melee, received a severe blow on the head. This man was at first reported dead, but inquiry elicited information that he is lying in a precarious condition in King Edward Hospital.

Among the men to be arrested were two Arabs, Mohammad Kaid and Mohammed Abouki, as detailed by the Belfast Telegraph. It is unusual here that we learn the names of both Kaid and Abouki, reflecting also how the reporting often conflated different ethnicities under umbrella terms like ‘coloured.’ Kaid was said to have fired on a policeman ‘with a five-chambered revolver,’ whilst Abouki ‘was sent to prison for six months’ for assault.’ Meanwhile, when another Arab was arrested, he faced cries of ‘lynch him.’

So serious was the violence in Cardiff that on 14 June 1919 the Sheffield Independent reported how the ‘Military [were] Ready To Take Action.’ The report in the Yorkshire newspaper described how:

The colour riots at Cardiff were resumed late on Thursday night, and there have been serious riots in other towns. It is understood that the Government is prepared to send troops to affected areas if the police are unable to control the riots. There have now been four deaths in Cardiff, and many were injured.

The Sheffield Independent then reported how ‘twenty persons were before the Stipendiary at Cardiff charged with participating in the riots.’ This time, white participants in the crowd were also arrested, with four men and one woman among that number. The woman, who ‘was said to have been arrested while flourishing a razor, was discharged,’ whilst the ‘majority of the men were remanded.’

Meanwhile the violence had spread even further down the Welsh coast to Barry, where three Black men ‘were sent to prison for one month for being in possession of loaded firearms in a street.’

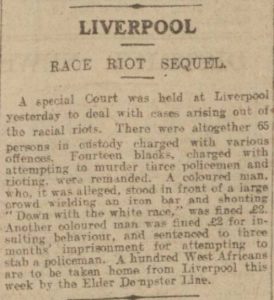

‘Race Riot Sequel’

Back in Liverpool, the Exeter and Plymouth Gazette on 17 June 1919 reported how a special court was held in the city to ‘deal with cases arising out of the racial riots,’ which saw 65 people in total in custody. The newspaper details how fourteen of the Black arrestees were remanded, ‘charged with attempting to murder three policemen and rioting.’

The short piece in the Devon newspaper ended with the following report:

A hundred West Africans are to be taken home from Liverpool this week by the Elder Dempster Line.

The Daily News (London) on 18 June 1919 followed up this brief report with the news that the British Government were going to do ‘all in their power to repatriate’ those involved in the riots, ‘so as to relieve the situation caused at Liverpool and Cardiff by the racial riots.’ Notice how this not seen as deportation, but rather the act of some benevolent government for its colonial subjects.

The Daily News (London) goes on to relate how the Ministry of Shipping was organising such ‘repatriation efforts,’ although they had encountered ‘great difficulty’ in providing ‘shipping for the purpose.’ Meanwhile, the newspaper put the figure at 200 passengers instead of the 100 outlined by the Exeter and Plymouth Gazette, dubbing the move as an ‘experiment.’ And should it ‘prove successful,’ another steamer would be sent from Liverpool to West Africa. Furthermore, another ship was set to be arranged for those with a ‘desire to return to the West Indies at the end of the month.’

It was hardly tackling the root of the problem: the racial misunderstanding and tensions that had arisen following the end of the First World War. Britain’s Black and ethnic minority populations were viewed as resolutely other, and instead of addressing the racism directly, the government’s solution was to ship the perceived problem away.

But still the race riots continued, and by 21 June 1919 they had spread to London, where a riot occurred in Cable Street, which later would be famed for its resistance to Oswald Mosley and his fascist organisation.

The Evesham Standard & West Midland Observer on 21 June 1919 detailed how a shop ‘kept by an Arab was stormed,’ with the shop occupants attempting to escape. The riot had emerged from the report that ‘some white girls had been seen to enter the house,’ which caused a crowd of 3,000 people to assemble there. The house’s occupants were eventually rescued by police, and ‘escorted for safety to Lemon Street Police Station.’

A month later, and those involved in the riots in Cardiff were sentenced at Swansea Assizes, as reported the Nottingham Journal. The newspaper details how ‘ten men were convicted of rioting, and were sentenced to various terms of hard labour, ranging from twenty months to three months.’ The report does not give the ethnicities of the men convicted.

After such violence, born out of the austerity of post war life, and suspicion over a new growing part of Britain’s population, it would have been a struggle for any Black or ethnic minority person making a life in the country, surrounded as they would have been by prejudice and misunderstanding.

But there were people who fought to overcome such adversity, some of whom we have celebrated in our blog here on the British Newspaper Archive, like Learie Constantine, who came to Britain in 1923, some four years after the race riots. When asked in 1964 by Charles Dimont for The Sphere how ‘British attitudes towards coloured people in Britain compare with when he first came to the country in 1923,’ Constantine said ‘there’s no comparison’ at all. The profoundness of this statement, given what interracial tensions Britain had seen, underlines the vital work done by Constantine and others in improving interracial relationships and fighting for Black equality, and the difficulties both he and others would have faced coming to Britain in the early twentieth century.