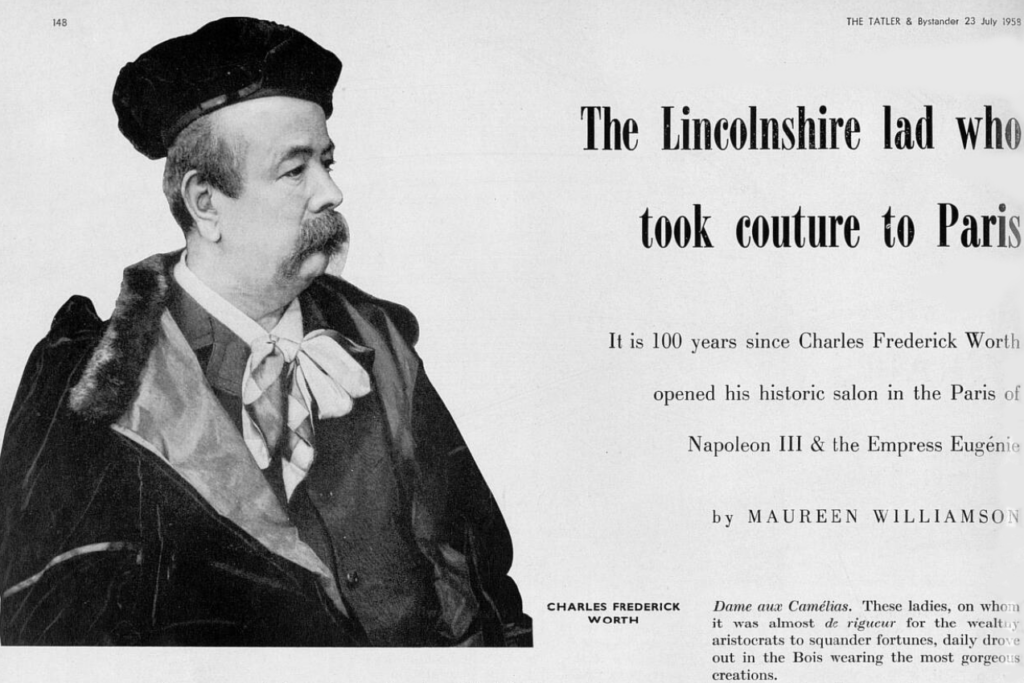

Known as the ‘first couturier‘ and the ‘Napoleon of costumiers,’ British fashion designer Charles Frederick Worth is regarded by many as the father of haute couture. Born in Bourne, Lincolnshire, on 13 October 1825, Charles Frederick Worth would make his name in Paris as the founder of the House of Worth, and the man who revolutionised the business of fashion.

In this special blog, we will explore the life and legacy of Charles Frederick Worth via newspapers published in his home country.

Register now and explore the Archive

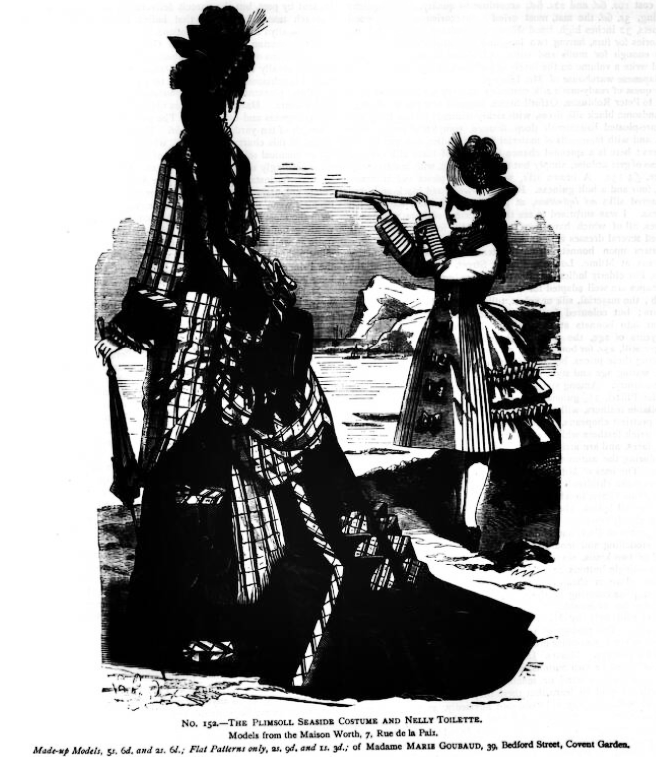

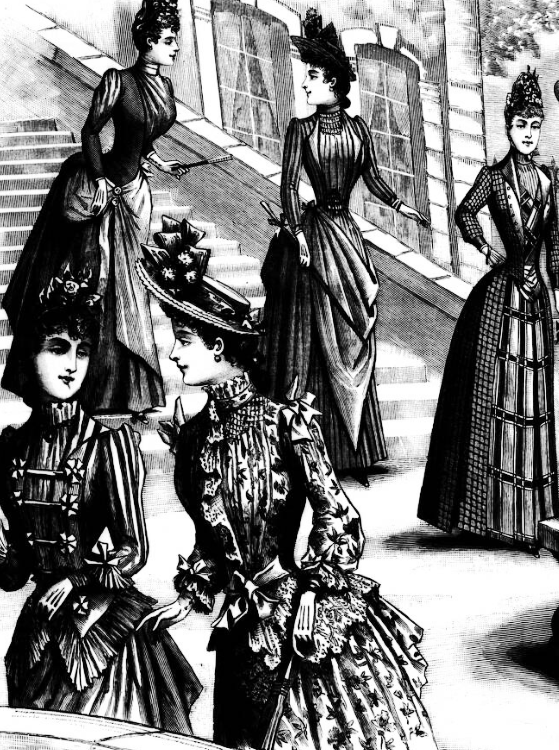

Explore our special fashion titles, like Myra’s Journal of Dress and Fashion, the Tailor & Cutter, the Gentlewoman and The Queen to find out more about fashion in the Victorian era.

Top tip from The Archive team

Early Life

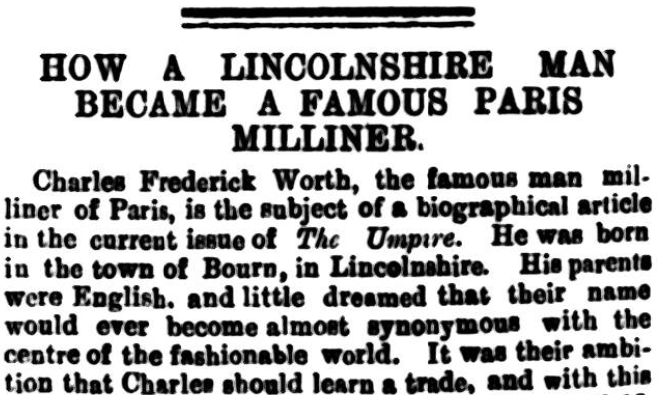

In July 1889, towards the end of Charles Frederick Worth’s life, the Peterborough Express published a piece entitled ‘How a Lincolnshire Man Became a Famous Paris Milliner.’ Although Worth was far from being simply a hat maker, the article contained some interesting details around the celebrated designer’s early life.

The Peterborough Express describes how Charles Frederick Worth was born in Bourne, Lincolnshire, to ‘English parents.’ Worth’s father was a lawyer, and his parents’ ambition was for their son to ‘learn a trade.’ However, an article published some fifteen years before in the Bradford Observer has it that due to ‘some family misfortune the children [of the Worths] were obliged to abandon their studies and seek their own livelihood.’

Whatever the truth of the Worth family’s circumstances, a young Charles was apprenticed to a printer. However, as the Peterborough Express outlines, the ‘boy was so fastidious that he disdained to soil his fingers even and evinced a strong hostility to handling type.’

A change of scenery was in order, and the newspaper describes what happened next:

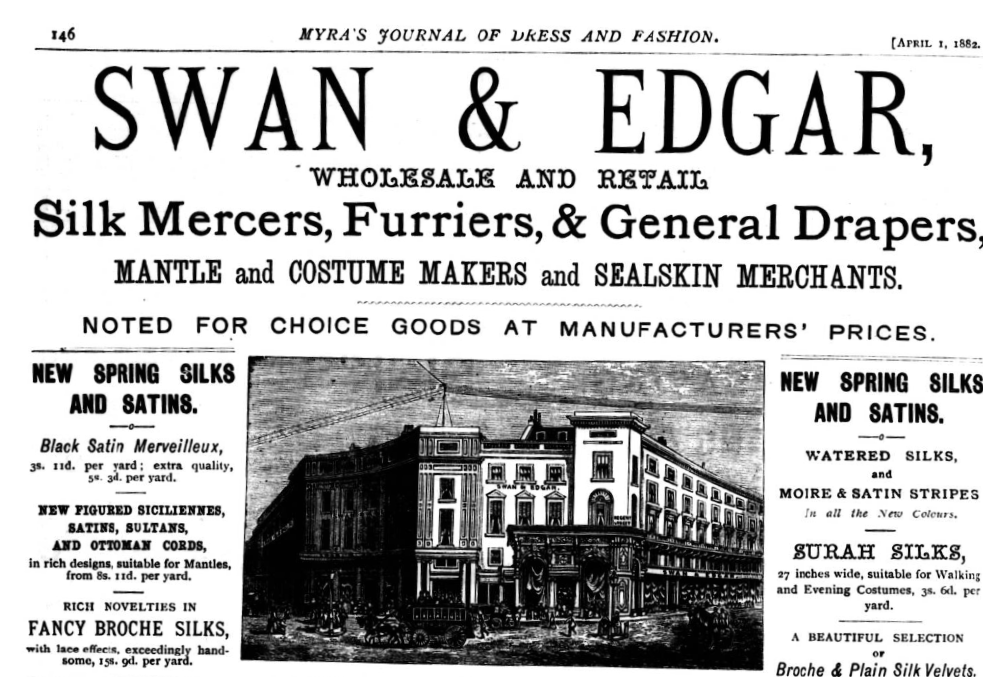

Against the kind remonstrances of his parents, he abandoned the printing office when he had been there but seven months and went up to London. The boy had previously written to a friend living the capital, asking for assistance in securing a position in a draper’s shop. His friends proved true, and after some difficulty procured for young Worth a situation in the house of Swan and Edgar.

The move proved to be an inspired one, as the Peterborough Express relates. Worth soon became a ‘favourite’ at the firm, and ‘for more than six years continued to grow in the firm’s favour, being treated by the heads of the establishment almost as a near relative.’

It was whilst in London that Charles Frederick Worth decided to make his next move, to Paris. According to the Peterborough Express piece, he had decided to become ‘a designer of fashions while talking with buyers for the firm.’ To this end, he resolved to learn French, and travel to the home of fashion, Paris.

Next Stop – Paris

Looking back at the life of ‘first couturier of this age,’ The Queen on 30 March 1895 describes how Charles Frederick Worth left ‘England at a desperately inartistic period.’ The piece sets the fashion scene, relating how the 1840s were ‘the days of high-stocks for men, poke-bonnets for women, and crooked-leg furniture covered with horsehair.’ Nothing, the writer for The Queen says, ‘could be more dreadful.’

Charles Worth was destined to change this dreary fashion outlook. Picking up the narrative once more, the Peterborough Express describes how a 22-year-old Worth joined the firm of Gagelin and Co. Here he would become a department head within a few years, and as the Leitrim Advertiser describes in March 1895, he would stay there for twelve years in all.

However, despite winning acclaim at Gagelin and Co., who were ‘noted for their silks,’ the firm ‘refused to take [Worth] into partnership,’ as the Leitrim Advertiser relates. The enterprising Worth had identified a gap in the Parisian fashion market, as The Queen describes:

‘Miss Flora McFlimsey of Maddison-square’ and all her friends, who found in Broadway nothing good enough to wear, were coming over to Europe to learn how to dress, and going to Paris for the latest fashions. Mr Worth saw all this and knew where his fortune lay. Soon after he had learned his business, he suggested certain enterprising movements in advance to the house in which he was employed. They hesitated and eventually declined to accept his suggestion, whereupon Mr Worth left their employ and started a business for himself in the very same premises in the Rue de la Paix, in which we find him now.

Undeterred, Charles Frederick Worth established his own design business, Worth and Bobergh, and it was during this period that he would find fame and fortune, as the main designer to the glittering court of the Second French Empire.

Empress Eugénie – The ‘Envy of All Womankind’

It was at the court of the Second French Empire (1852-1870), presided over by Emperor Napoleon III (1808-1874) and his wife the Empress Eugénie (1826-1920), that Charles Frederick Worth would make his name.

The Leitrim Advertiser describes how in 1858 Worth set up his own premises at Number 7, Rue de la Paix, in 1858, where he employed fifty members of staff. And it was the Second Empire, which was then ‘in the height of its prosperity,’ that Worth was destined to serve, as the same newspaper describes:

The Empress Eugenie, then in the prime of womanhood and the full perfection of her incomparable beauty, was delighted with the dresses invented for her by the brilliant young Englishman. Worth speedily became the dressmaker par excellence to the Imperial Court. Its reigning belles, the Princess de Metternich, the Princess Anna de Murat, the Countess de Brigode, and others, became his patrons, and sought not only his creations in the way of gowns and wraps, but his counsel as well in all matters connected with the toilette.

The Peterborough Express in 1889, meanwhile, describes how the Empress Eugénie was an ‘ardent admirer of [Worth’s] skill.’ At this time, furthermore:

There was a great craze for fancy dress balls, and the Empress, who was an exceedingly pretty woman, had many dresses designed by Worth. This added to his already established reputation as a costumier.

The Empress Eugénie and Charles Frederick Worth proved to be a fashion match made in heaven, a nineteenth century precursor to Audrey Hepburn and Hubert de Givenchy, or Madonna and Jean Paul Gaultier. Together they pioneered the trends of the century, as the Sheffield Weekly Telegraph outlines in April 1889:

When the Empress Eugenie was at the height of her fame and glory it was Worth who made Her Majesty the pink of fashion and the envy of all womankind. It was the Empress who first suggested and Worth who first fashioned that amplitude of skirt, the crinoline. Worth has dressed many charming women, but never one as charming as the unfortunate Empress.

The House of Worth – ‘Revolutionising Female Dress’

In 1870 Charles Frederick Worth parted ways with his Swedish business partner Otto Gustaf Bobergh to form the iconic House of Worth. But what kind of designs did he pioneer?

The Leitrim Advertiser in March 1895 provides a glimpse through Worth’s career highlights, looking first at his ground-breaking submission to the 1855 Paris Exposition:

His contribution, a court mantle in white silk covered with elaborate embroidery in gold thread, the artistic pattern of which was designed by himself, carried off the first prize almost without contestation. This splendid mantle, even in those days of comparatively low prices, was valued at 3000 dols.

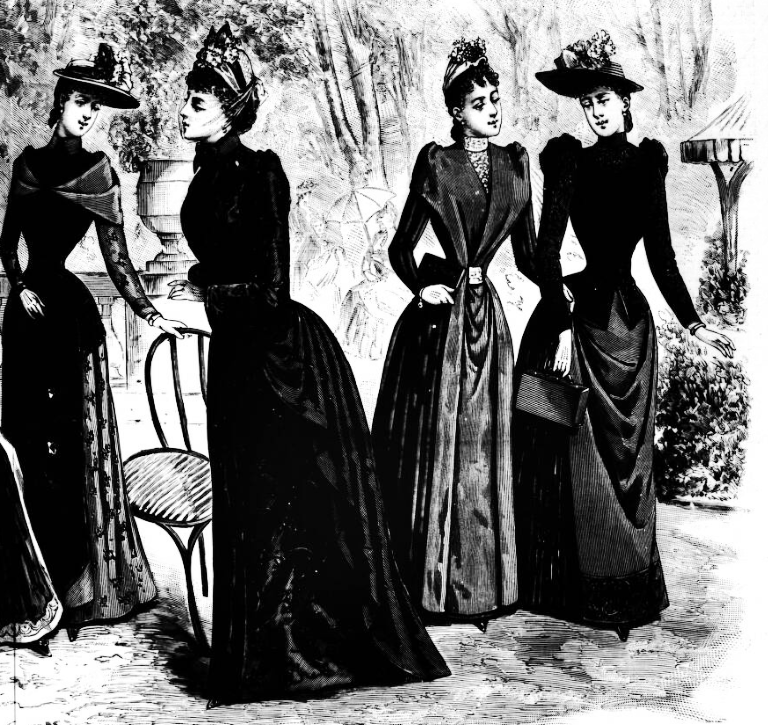

The newspaper then looked at the styles for which Charles Worth was responsible, the designs ‘that were destined to revolutionize the world of feminine dress:’

Amongst these was the short-skirted walking costume, with jacket and skirt composed of the same material. The first dress of this style was made for the Empress Eugenie, and was in grey silk trimmed with black velvet ribbon. He thus suppressed the trailing skirt for street wear – a fashion at once unclean and inconvenient.

The Peterborough Express describes another of Charles Frederick Worth’s sartorial triumphs:

One remarkable feat was the making of a dress which took 100 yds of silk. It was in light glace taffetas, and had three shades of purple, varying from lilac to violet; when completed the dress looked like an immense bouquet of violets, having a skirt covered with close full ruchings in three shades.

It was little wonder then that the Lincolnshire born designer captivated the world with his designs. The Leitrim Advertiser goes on to relate how:

Worth made dresses not only for the royal ladies of Europe, but for the queens of society, both in Europe and United States, and for the queens of the foot-lights as well. His first royal customer was Donna Maria da Gloria, then Queen of Portugal. For years thereafter there was scarcely a princess married in all Europe – outside of the ladies of the Imperial family of Germany, whose principles forbid them from ever ordering anything to be made in Paris – that did not have a group of Worth toilettes included in her trousseau. The Dowager Empress of Russia and the Queens of Italy and Portugal became his constant customers.

The Empire of Charles Frederick Worth

With Charles Worth’s success came his empire, both the House of Worth and his home in Suresnes, located in the Paris suburbs. By the time of his death in 1895, the Leitrim Advertiser described how the fashion house employed some 1,200 members of staff, who between them produced from 6,000 to 7,000 dresses a year.

Meanwhile, in April 1874, the Bradford Observer reprinted an account of Worth’s life and business from the Treasury of Literature, which related just how the House of Worth was set up:

The workshops (ateliers) are immense in size and number. Each one has its speciality: one for the corsage, one for jupons, another for trimming, &c. About a thousand workpeople are employed in the confection of robes and costumes, which are sent to all parts of the world.

The same account also portrays Worth’s home as a place of rare grandeur:

Six or eight miles from Paris, on the Versailles route, lies the pretty town of Suresnes, at the foot of Mount Valérian, and in front of the Bois de Boulogne. On the opposite side of the street, near the railway station, rises from within a high garden-wall a red brick chateau, in the form of the letter L, with a towered and turreted roof. It is the residence of Worth, the Napoleon of costumiers.

The writer, who had ‘visited numerous palaces of kings in Italy, Austria, and Germany,’ claims to have been ‘dazzled’ by the sight of Charles Frederick Worth’s home in Suresnes, almost just as much as he was by the sight of the man himself.

The Man Himself

In 1874 the writer for the Treasury of Literature described their first encounter with Charles Frederick Worth:

…for the first time we were dazed, and while in that stupefied state in came ‘Monsieur Vort’ in a flowing grey robe that fell to his heels, lined with pale yellow, with a deep vest to match, and numerous other overlapping appliances that modified and gave elegance to a costume as unique as it was comfortable.

According to other newspapers of the time, this visit was a rare one, as The Queen in 1895 labelled the designer as ‘almost a recluse.’ Having married Marie Vernet in 1851, with whom he worked at Gagelin and Co., the couple settled at what was then the ‘small villa’ at Suresnes. The villa, which was near the railway station, was expanded over time, and Worth commuted into the city every day.

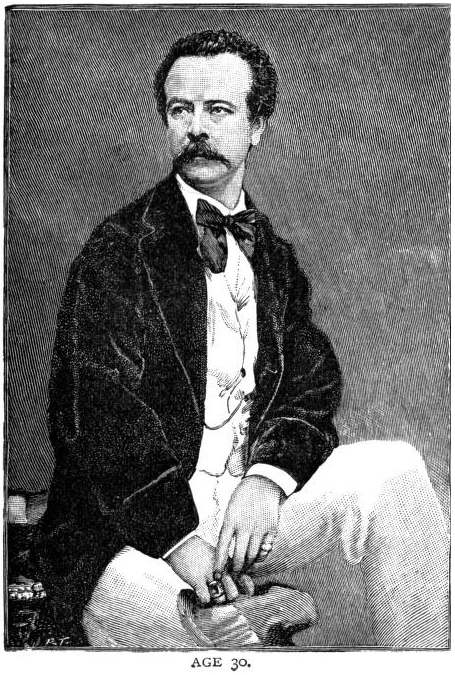

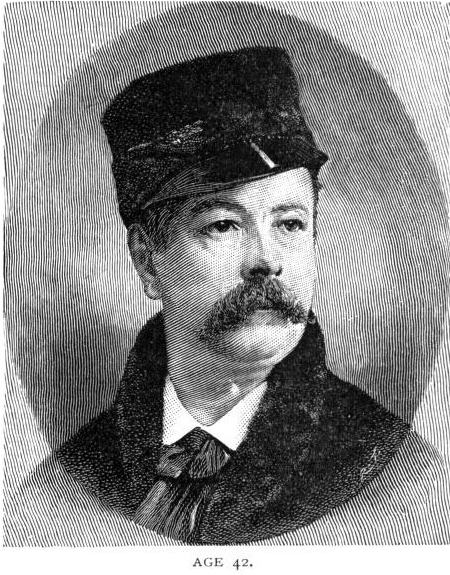

The article on ‘The Paris Dressmaker,’ as printed in the Bradford Observer in April 1874, gives this portrait of Charles Frederick Worth:

In person Mr Worth is of medium English height, strongly but not stoutly built. He has black eyes, hair and moustache dark, and a fully developed forehead, which a phrenologist would doubtless say is crammed with form, perception, colour, taste…He is not a bit ‘Frenchy.’ He retains much of the bluntness which characterises the English, and has ‘taken on’ very little of the suavity…of the French…He is modest and unaffected…and would pass for an unassuming, honest, common…sort of man, thoroughly conscientious in a profession which he has raised to the dignity of a fine art.

The piece also offers insight into Worth’s perfectionism as a designer, describing how ‘often when a dress is finished which fails to please him, he has it quite taken to pieces and remade.’ Such perfectionism had a price, that of no less than £20, or about £1,300 in today’s money – couture indeed.

Worth had further revolutionary ideas about fashion. He is recorded as stating by the Bradford Observer how he ‘did not see the slightest objection to women wearing trousers with a tunic.’ Interestingly, however, it seems Charles Worth did not see himself as a designer so much as a businessman, the writer for The Queen in 1895 relating how:

Some years ago I asked Mr Worth to allow me to photograph his grounds and give a published description of his house. He replied most modestly and firmly: ‘I am a business man and shall always remain one. Were I to accede to your wish I might pose as something else, and this I have no wish to do.’

Shrewd and modest, The Queen tells of Charles Worth’s charity to the less well off of Suresnes, ‘where he was greatly beloved.’

‘The First Couturier of This Age’

On 10 March 1895 the great couturier Charles Frederick Worth passed away, the Brockley News, New Cross and Hatcham Review reporting on 22 March 1895 how the designer had ‘died at his private residence in Paris on Sunday night.’ The newspaper remembered him as:

…the original founder of the business, the autocrat of the toilet, before whom even Empresses and prime donne, to say nothing of the stars of the demi-monde, used to bow their heads during the palmy period of the Second Empire.

Over a week later, on 30 March 1895, The Queen related how:

Mr Charles Frederick Worth, the first couturier of this age, and whose death in Paris has been the subject of much remark the world over, was buried last week in the family vault in the village of Suresnes-sur-Seine. On the Wednesday previous a service for the dead was held in the French Protestant Church in the Avenue de la Grand Armée, Paris.

The designer had left a remarkable legacy, his achievements being such that they were recognised even his lifetime, the Sheffield Weekly Telegraph naming him ‘the greatest creator in creation.’ The Brockley News, however, upon Worth’s death, decided to concentrate on his Englishness, commenting how ‘his career may be regarded as a curious testimony to the superior capacity of Englishmen even in a field supposed to be the exclusive property of French genius.’

Even with such a career, being the most ‘celebrated of all Parisian dressmakers,’ the Leitrim Advertiser addresses the irony of how ‘the only Queen in all Europe who never ordered a toilette from him is the one of whom he was a born subject.’

‘Its Soul and Brain and Sinews’

The Leitrim Advertiser provided a further tribute to the late designer, penning how:

Worth was not only the head of the vast establishment in the Rue de la Paix, but its soul and brain and sinews as well. He created the pattern dresses, ordered materials and trimmings to be manufactured, often his own designs, and superintended in personal all the delicate finishing details of a toilette, such as the shaping and trimming of a corsage, the tying of scarfs or of ribbons, and the placing of artificial flowers on the skirt. He excelled in combining colors, sweeping aside piece after piece of silk till the exact union of hues that was at once the most effective and the most artistic had been reached.

Alongside his flair for business sat his artistic genius, the newspaper poetically adding how:

He studied the portraits of beauties and celebrated female personages of by-gone ages to glean ideas for new styles, as he observed the blending of colours in the plumage of birds, or the petals of flowers, or the accidental combination of the pale green of young grass in the spring with the warm red of the earth in a freshly-ploughed field.

What was next though, for the House of Worth? The Queen describes how Charles Frederick Worth’s two sons, Jean Philippe and Gaston, had inherited ‘the entire control of the concern,’ which was said to be producing ‘10,000 costumes a year.’

The House of Worth was eventually closed in 1956, although the brand was revived in 1999. The legacy of Charles Frederick Worth lives on, however, in the fashion houses of today, designers from the twentieth and twentieth-first centuries following in the footsteps of the father of haute couture himself.

Find out more about Charles Frederick Worth, the history of fashion, and much more besides, in the pages of our newspaper Archive today.