1889 was the year of the Cleveland Street scandal, in which a male brothel was raided in Cleveland Street, in London’s West End. At the time, sexual acts between men were illegal in Britain, and those who visited the house of assignation on Cleveland Street faced prosecution. However, due to the high social standing of many of the clientele of 19 Cleveland Street, only a few men faced prison time, as the British government were accused of covering up the scandal in order to protect members of the establishment.

In this special blog, we shall explore how newspapers from the time reported on the Cleveland Street scandal. We shall look at how restrictions were placed on the British press, and examine how newspapers from Britain’s then empire reported on the incident. We shall learn, furthermore, how homosexuality was demonised by the press, and characterised as an aristocratic vice, whilst understanding how the scandal highlighted the hypocrisy that was embedded at the heart of Victorian society.

Please note before continuing, newspapers and other sources from the time often use offensive language to describe LGBTQ+ relationships, making it difficult for us today to read these accounts.

Register now and explore the Archive

‘A Horrible Scandal’

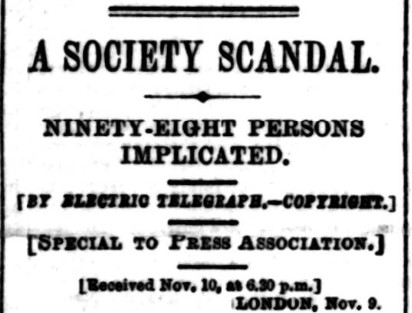

Although the actual uncovering of the male brothel in Cleveland Street occurred in the summer of 1889, it was not until the winter of that year that news of the scandal reached the press. One of the first mentions of the incident we found was not actually from the British press, but rather from New Zealand title the Lyttelton Times, which carried tidings of a ‘society scandal‘ on 11 November 1889:

A horrible scandal in connection with a private West End Club is reported. Ninety-eight members in all are implicated. Thirty-one warrants have been issued but will not be executed on the understanding that the persons connected with it leave the United Kingdom.

Not only did the article allude to several men of high standing being involved in the scandal, but it also highlighted how the British press was silent on the matter:

The list of offenders features future Dukes, the sons of Dukes, Peers, Hebrew financiers, many honourable persons, and several officers of the Imperial Army. All the latter have suddenly resigned their commissions. The offenders have fled. The newspapers have suppressed reference to the scandal, but there is no doubt of it having taken place.

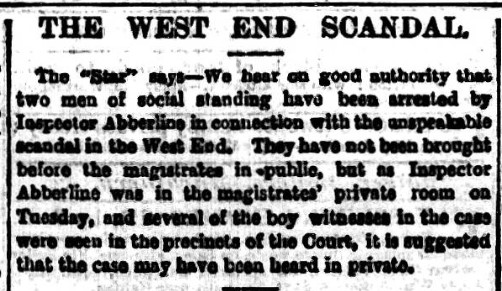

A few days later, on 15 November 1889, news of the ‘West End Scandal’ made it to the pages of British newspapers. Still, the particulars of the events were patchy, surrounded by rumour and innuendo. This report is from the Bradford Daily Telegraph:

We hear on good authority that two men of social standing have been arrested by Inspector Abberline in connection with the unspeakable scandal in the West End. They have not been brought before the magistrates in public, but as Inspector Abberline was in the magistrates’ private room on Tuesday, and several of the boy witnesses in the case were seen in the precincts of the Court, it is suggested that the case may have been heard in private.

For true crime fans, this is the same Inspector Abberline who investigated the Jack the Ripper crimes a year previously.

‘Abominable Charges’

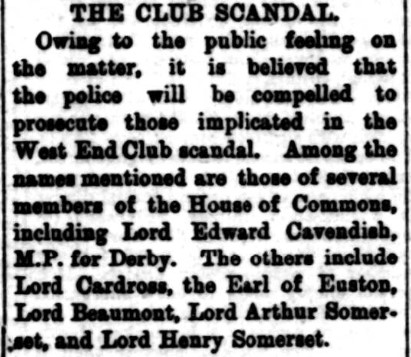

It was down to the New Zealand newspaper the Lyttelton Times to reveal more about the feelings of the British public in relation to the Cleveland Street revelations. The newspaper too began to name names, something the British press (with one notable exception) had shied away from doing. This report was published by the paper on 20 November 1889 under the headline ‘The Club Scandal:’

Owing to the public feeling in the matter, it is believed that the police will be compelled to prosecute those implicated in the West End scandal. Among the names mentioned are those of several members of the House of Commons, including Lord Edward Cavendish, M.P. for Derby. The others include Lord Cardross, the Earl of Euston, Lord Beaumont, Lord Arthur Somerset, and Lord Henry Somerset.

It did appear that a police investigation was being mounted into the activities at Cleveland Street. Another international newspaper, this time Belize’s Colonial Guardian, reported how ‘six sittings have been held in camera at the Marlborough street court to inquire into abominable charges made against members of a West End club.’ The Belize-based paper also reported how the scandal was said to involve ‘an eminent Liberal politician, an officer of the royal household, and several peers.’

A Libel Accusation

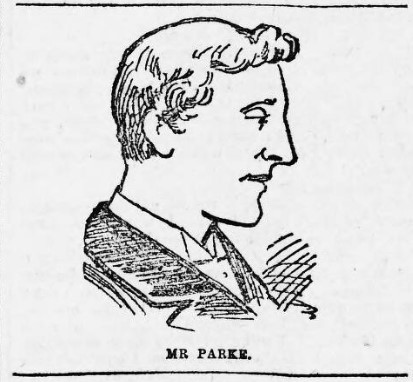

One British newspaper, however, did print one of the names of those connected with the Cleveland Street scandal. On 25 November 1889 Exeter’s Western Times reported how:

Mr. George Lewis was granted a warrant at Bow-street Police Court on Saturday for the arrest of Mr. Ernest Parke, editor of the North London Press, for an alleged libel on Lord Euston in connection with the West End scandal, and the warrant was placed in the hands of Sergt Pargeter for execution.

Despite Ernest Parke offering the Commissioner of the Police ‘four sureties in £500 each,’ the newspaper editor was sent to the cells.

Parke’s arrest stirred up public feeling. A week later, the Dundee Evening Telegraph published the ‘following appeal:’

In the interests of justice, it is desirable that Mr Parke’s defence to the criminal action for libel brought against him by the Earl of Euston should not be unfairly weakened by want of money. The Parke Defence Fund has there been started.

The Cleveland Street scandal highlighted the gulf between the rich and the poor: those accused of what was then a crime could get away with it because they were wealthy and powerful. When Ernest Parke sought to uncover those who were set to get away with it, he was championing the cause of free speech and going against what was perceived as the upper-class, polluting, vice of homosexuality.

Parke’s American contemporaries, meanwhile, ‘continued to publish sensational despatches from London respecting the West End scandals, and names are mentioned with the utmost freedom.’

‘The Truth About the Great Scandal’

The police investigation into the scandal had gone international, the Bradford Daily Telegraph reporting how an English detective named Shan had arrived in Berlin from London, en route to St Petersburg. His mission? To ‘obtain an important statement from one of the fugitives’ involved in the affair.

At the same time, pamphlets about the Cleveland Street scandal were doing the rounds. On 6 December 1889 the Sheffield Independent described how:

There is being scattered broadcast in London a statement professing to give ‘the truth about the great scandal,’ and certainly stating the facts which are common talk in greater detail and with far more circumstance than before. As this is being sold so rapidly in the streets that by nightfall double and even treble the price was demanded for a copy, it affords yet another illustration of the mischief that has been caused by attempts to hush up the affair.

The Sheffield Independent also detailed how ‘leading ministers,’ especially Home Secretary Henry Matthews, were being attacked, with their critics ‘waxing bolder daily.’ The Government’s cover up was at risk as ‘statements are now being made in print and names specified which were only whispered two or three weeks ago.’

Meanwhile, such gossip was made very real by the publication in Metropolitan Police paper the Hue and Cry of a description ‘of the son of the duke who is ‘wanted’ in connected with the alleged offences, while a very broad indication is afforded as to another a name which not even the most reckless has yet dared to put in print, though it has been freely enough mentioned in conversation.’

The message to the government? Act now, the Sheffield Independent penning how ‘all this is very serious, and Ministers can scarcely delay long in instituting such proceeding as shall allay the growing excitement.’

The Libel Prosecution

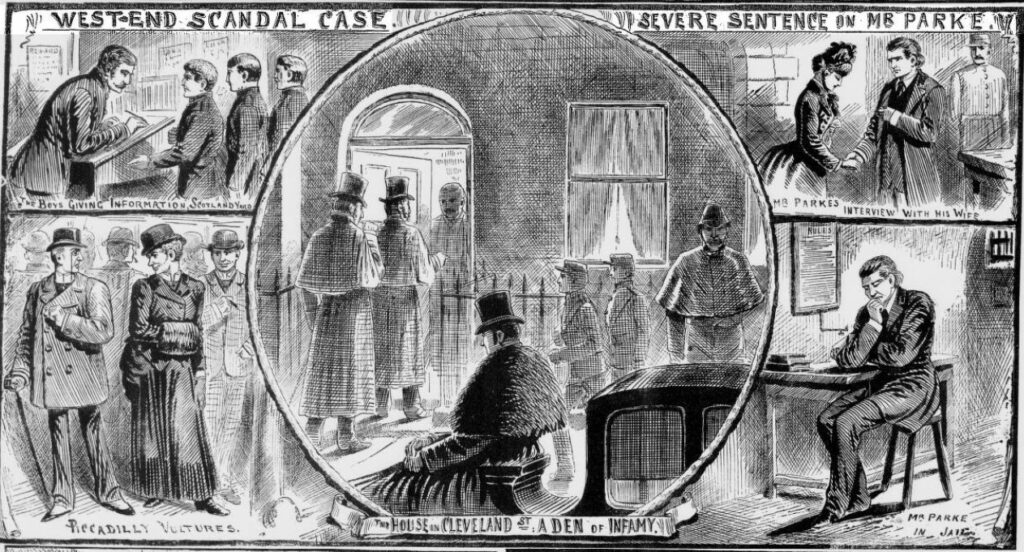

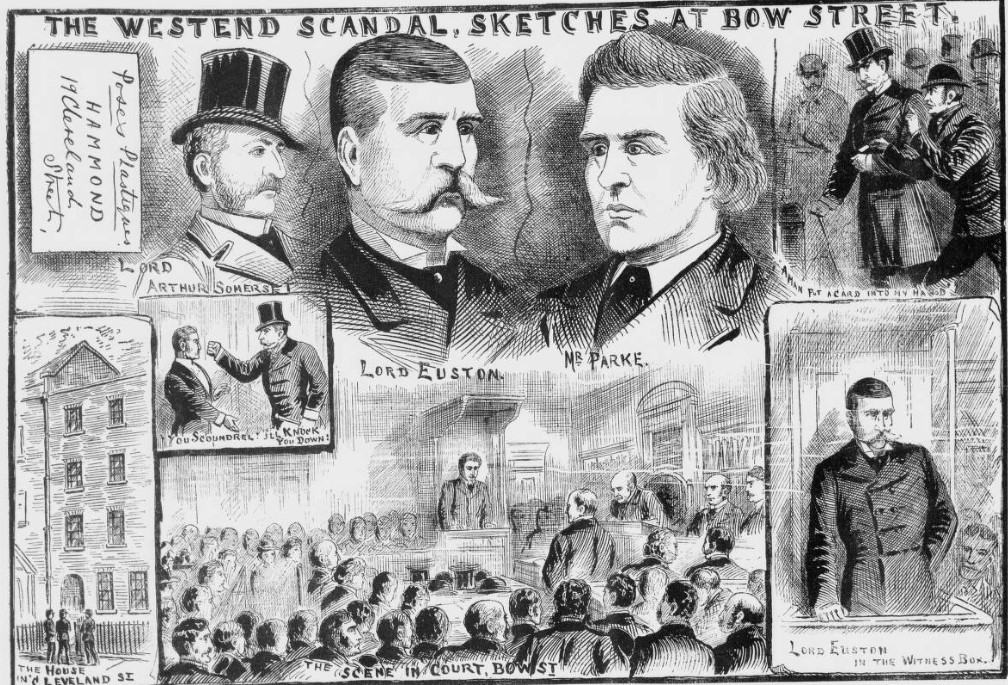

Meanwhile, newspaper editor Ernest Parke’s trial for libel against Lord Euston was held, crime-focussed newspaper the Illustrated Police News providing commentary on the proceedings. It gave some background to the case, describing how the suit had come about:

Mr. George Lewis said Lord Euston complained of a libel published in the North London Press. The libel was published on 16th of November…The libel referred to a previous article published in the same paper about what were called ‘unspeakable scandals,’ and contained a passage in which it was stated that amongst the number of distinguished criminals who had been allowed to escape was Earl Euston, eldest son of the Duke of Grafton. The article concluded by warning Mr. Matthews that he must take action in the matter, as ‘there were being committed in our midst certain foul crimes which could not be tolerated.’ This was a distinct allegation that the Earl of Euston had committed felony of the most grave character, and that was the libel for which he (Mr. Lewis) should ask for the defendant’s committal for trial.

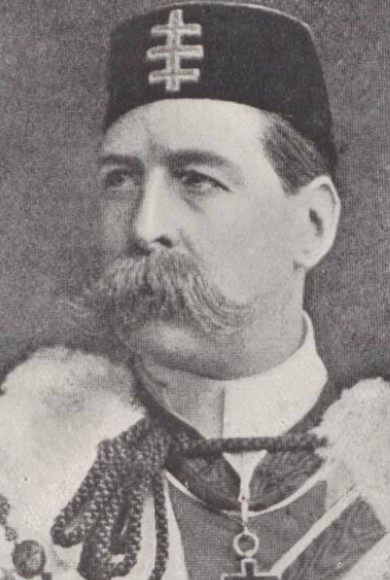

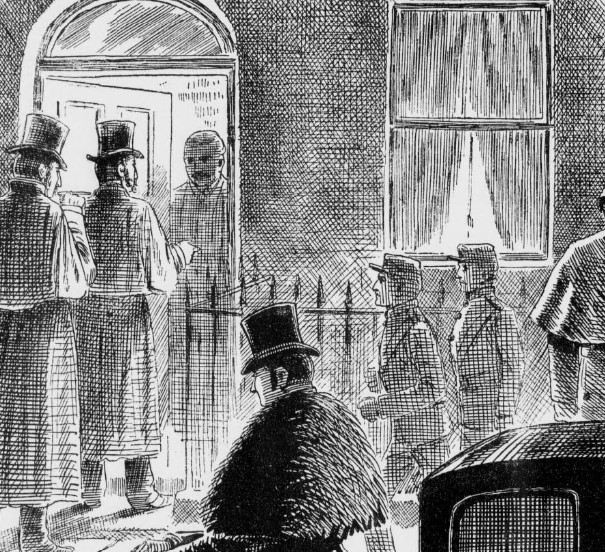

Lord Euston ‘denied that he had ever committed any crime,’ although he had visited the Cleveland Street address. He related this slightly unlikely story:

…one evening in May or June last he walking in Piccadilly, when a man put into his hand a card, on which he found the words, ‘Poses plastique,’ and an address in Cleveland-street, Tottenham-court-road. One night, a short time afterwards, the earl went to this house. A man opened the door to him, and asked him for a sovereign. Then the man made certain proposals to the prosecutor, who, very indignant, threatened to kick him out of the place. He (the earl) immediately left the premises. This was, in fact, all he knew about the house.

The Illustrated Police News provides a vivid description of Lord Euston, who looked younger than his forty-one years. He is described as being ‘tall, square-shouldered, and heavily-built, and has the air and carriage of a cavalry man,’ with a permanent scowl gracing his ‘ruddy complexion.’

If the newspaper had cast the aristocrat as the villain, Ernest Parke was the hero of the piece, with his ‘pale, earnest, and intellectual face.’ The Illustrated Police News describes him as looking ‘more like a hard-working student than the defendant in a newspaper libel case,’ whilst also noting his popularity with the ‘newspaper men, among whom he seems to enjoy warm popularity and substantial esteem.’

The almost pantomime juxtaposition belies the battle between perceived forces of good and evil, poor and rich, innocent and sinning. But which would win out?

‘How the Scandal Leaked Out’

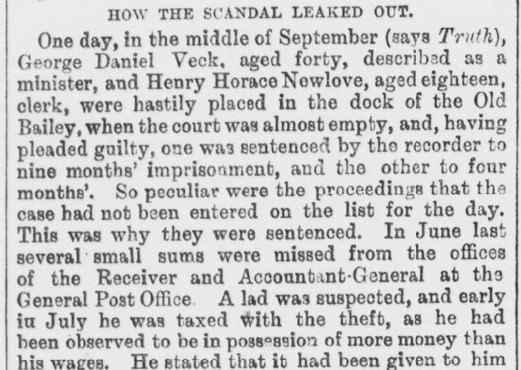

The Illustrated Police News report on the libel prosecution also contains some interesting information about ‘how the scandal leaked out.’ The piece describes how:

One day, in the middle of September (says Truth), George Daniel Veck, aged forty, described as a minister, and Henry Horace Newlove, aged eighteen, clerk, were hastily placed in the dock of the Old Bailey, when the court was almost empty, and, having pleaded guilty, one was sentenced by the recorder to nine months’ imprisonment, and the other to four months.’ So peculiar were the proceedings that the case had not been entered on the list for the day.

But why had Veck and Newlove appeared at the Old Bailey? The Illustrated Police News explains:

In June last several small sums were missed from the offices of the Receiver and the Accountant-General at the General Post Office. A lad was suspected, and early in July he was taxed with the theft, as he had been observed to be in possession of more money than his wages. He stated that it had been given to him by a man named Hammond, of Cleveland-street, Fitzroy-square. The boy also said that several of his fellow messengers were in the habit of going to this house and receiving money. The house was watched and the boys’ statements were verified. Warrants were issued against Hammond, Veck, and Newlove. Hammond fled the country, Newlove was arrested on July 8th, and Veck on August 20th.

The article then explains that two other people were ‘smuggled into prison,’ one of whom was a ‘nobleman connected with the Court.’ He had since fled, resigning his position in the army, leading the Illustrated Police News to ask:

If this is not one law for the obscure and another for those highly-placed, what is?

‘Infinite Trouble and Vexation’

Rumours around the identities of those involved in the Cleveland Street scandal continued to swirl, with some names being printed outright by the international media. New Zealand newspaper the Lyttelton Times on 9 December 1889 reported how ‘Lord Arthur Somerset, major of the Horse Guards, who is son of the Duke of Beaufort, is openly accused of most villainous conduct.’ Somerset had subsequently ‘fled the country.’

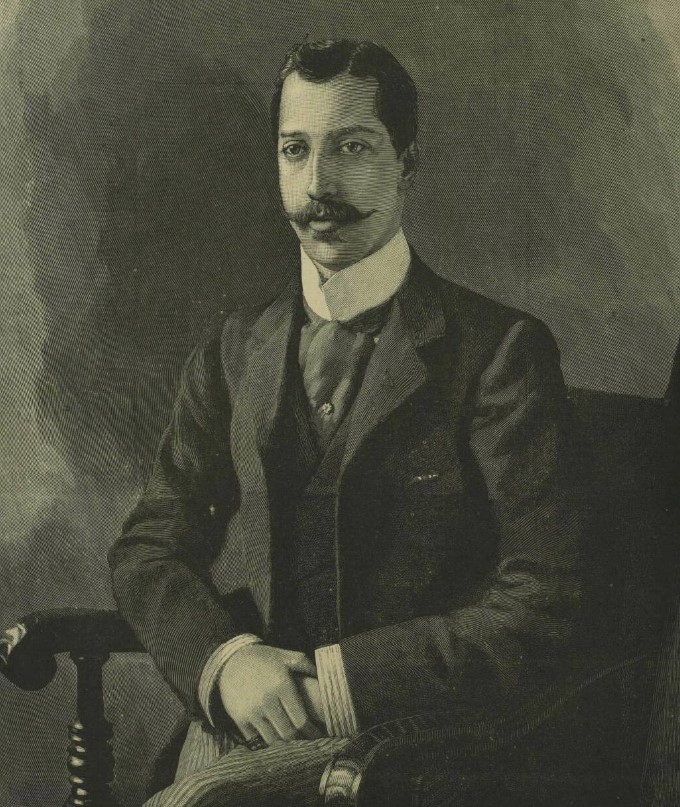

The article also made mention of a bigger fish, Prince Albert Victor, the Duke of Clarence, the eldest son of the Prince Of Wales. It reported how he had ‘more pressing reasons for his trip to India than pleasure,’ and that the prince was intending to remain there until ‘the scandal excitement has subsided.’

The Lyttelton Times, meanwhile, reported on corruption at the highest levels of the establishment. After a meeting of the Privy Council, six sittings at the Marlborough Police Court and requests from Police Commissioner James Monro for warrants to be issued, it was alleged that the Prime Minister himself Lord Salisbury ‘quietly gave warning to the accused, who left for the Continent.’ Other names mentioned by the newspaper included those of Lord Ronald Glover and Lord Erroll.

On 14 December 1889 the Illustrated Police News described how the affair was ‘continuing to give infinite trouble and vexation’ in high quarters, including those of the Prince of Wales. The newspaper reported how:

The London correspondent of a Liverpool contemporary hears with regret that Marlborough House is daily assailed with anonymous letters of a most outrageous character, being upon the West-End scandals. Not only the Prince of Wales, but the princess is directly addressed in communications of a monstrous character.

A Not Guilty Plea

Meanwhile, Ernest Parke, the proprietor and editor of the North London Press pleaded not guilty to the charge of libel at the Old Bailey, as reported the Lancashire Evening Post. Parke was defended by a Mr. Asquith, likely to be Herbert Asquith, who was working as a barrister at the time. He would later become Prime Minister during the First World War.

Asquith put forward the contention that ‘the alleged libel was true in substance and in fact, and that is publication was for the public benefit.’ Lionel Hart, for the prosecution, did not counter, but ‘applied for the postponement of the trial,’ because Parke’s plea had only just been submitted. The judge in the case agreed, despite Parke being ‘ready and anxious to meet the charge,’ and the case was set to ‘stand over until the next sessions.’ Parke was released on bail.

The tentacles of the Cleveland Street scandal were long. On 21 December 1889 the Lahore-based newspaper the Civil & Military Gazette reported how solicitor Arthur Newton had been arrested. Newton had watched the proceedings of Parke’s libel trial, and he had been charged with ‘conspiring to defeat the ends of justice by screening people alleged to be incriminated in the West End scandals.’

The arrest of Newton was, apparently, an effort ‘to refute the alleged charge of connivance on the part of the Government at the escape of prominent delinquents in the case.’

Silence Is A Mistake

The damage to the government had been done, however, by the Cleveland Street scandal. In trying to cover up the activities of the members of high society, it had only created more rumours.

Canadian newspaper the Toronto Daily Mail on 23 December 1889 reported on the rumours about the involvement of Prince Albert Victor in the case. Indeed, the newspaper condemned the ‘dastardly journalism’ of its American contemporaries, after a picture of the royal was printed alongside a description of the scandal. The Toronto Daily Mail reflected how ‘a more atrocious or more dastardly outrage was never perpetrated in the press.’

The article went to thoroughly dismiss the rumours about Prince Albert Victor, writing how:

Speaking with some knowledge of the charges in question and the persons who are really compromised by them, I assert that there is not and never was the slightest excuse for mentioning the name of Prince Albert Victor in association with them…it is a mistake for the English press to maintain absolute silence on the subject.

Conclusion

In the end, the scandal died down. Ernest Parke was found guilty of libel in January 1890, effectively clearing Lord Euston’s reputation. However, the damage was done. Newspapers continued to reinforce in the public’s mind that male homosexuality was a dangerous and aristocratic vice, something that was built on the 1895 trial of Oscar Wilde.

However, the house at the centre of the scandal, 19 Cleveland Street, became a symbol of the homosexual and other marginalised communities. It is an important locus of London’s and indeed Britain’s LGBTQ+ history. As for the scandal itself, it represents the absolute fear and disgust that members of the historic LGBTQ+ plus community faced. Homosexuality was something that had to be kept to the shadows, indeed a criminal act, and something that the government was at pains to repress.

19 Cleveland Street no longer stands, but we can remember it through the pages of our newspapers today. Find out more about the Cleveland Street scandal, LGBTQ+ history and much more besides, in our Archive today.