In the 1940s the jitterbug, a type of swing dancing that was pioneered by African American communities in New York during the early twentieth century, took the United Kingdom by storm. The energetic dance, which featured elements of the jive, the charleston, and other swing dances, divided Britain, with it being embraced by those who flocked to dancehalls up and down the country, whilst others viewed it as a morally dangerous American import.

In this special blog, using newspapers from the 1940s, we will take a look at the differing attitudes towards the jitterbug. We will examine how the jitterbug had entered the public consciousness long before American soldiers came to British shores and how the craze continued even after the Second World War ended.

Register now and explore the Archive

Thrilling Music

Let’s start this exploration of the jitterbug by first getting under the skin of the dance. This is something that a journalist from Belfast publication Ireland’s Saturday Night did in October 1940, as they examined ‘The Jitterbug of the Ulster Ballroom.’

The scene is set perfectly, so that you can almost imagine taking to the floor to dance in the latest fashion:

Something ‘gets you’ when you hearing the snoring of the ‘saxes,’ the catcalling of the trumpets, the banshee wail of the violin, and the prankish tinkle of the piano – all beaten into a mad, wild thing by the staccato throbbing of the drums and the boom of the double-bass. Stirring music? Of course! It is thrilling music, pulsating with a crazy, rhythmic restlessness that… makes you want to dance, makes you want to jitter, makes your toes open and shut – plays all kinds of merry, mischievous tricks on you!

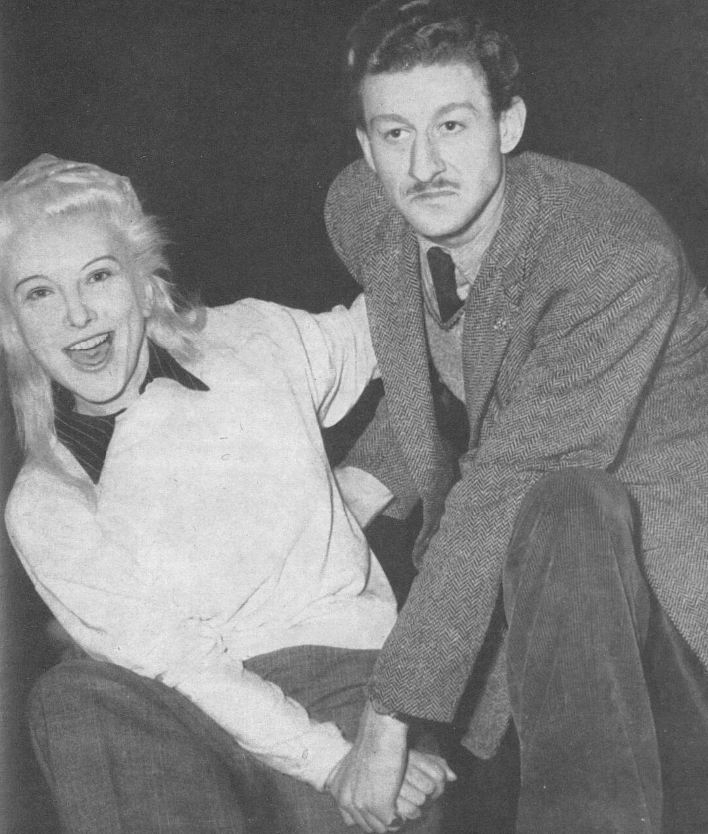

Enjoy this scene from 1939 film Blondie Meets the Boss to get even more of a flavour of the jitterbug. Indeed, it was thanks to such films as Blondie Meets the Boss that the jitterbug made its way across the Atlantic before American servicemen arrived on British shores.

The Latest Dance Craze

Newspapers from The Archive demonstrate how the jitterbug was taking the United Kingdom by storm in the early 1940s. On 19 March 1940 prominent Scottish newspaper the Edinburgh Evening News described how the Palladium Theatre at Fountainbridge, being ‘always abreast of the times,’ had organised a ‘Jitterbug Competition.’ The newspaper explained how the jitterbug was the ‘latest dance craze,’ and it was a spectacle being enjoyed by ‘large audiences.’

At the other end of Britain, just a few days later, local London paper the Streatham News was reporting on the South London Jitterbug Championship. The dance, it seems, had become so popular that ordinary people were participating in it. The Streatham News described how:

This crazy new dance, imported from America, is an amazing spectacle, and roused those who watched it to almost as great a state of enthusiasm as those who took part. Which is saying something!

In the end, Fred Gambriel of Wimbledon and Jessie Hurrell of Tooting took home the £5 prize, and championship silver cups.

The Jitterbug Jitters

There were some, however, who were not enthralled by the exciting new dance. Large regional paper the Liverpool Echo on 3 April 1940 published an article under the headline ‘jitterbug jitters.’ This piece outlined how Leeds City Council had been asked to ban ‘jitterbug dancing in the licensed halls of that city.’ As we shall see, there was a fear amongst dancers of a more conservative persuasion that the jitterbug posed a threat to more traditional, British, dances.

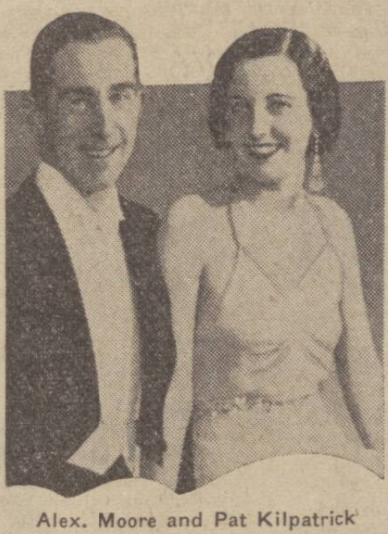

However, the citizens of Liverpool could make their own minds up on the jitterbug, as the city was to be visited by professional dancers Alex Moore and Pat Kilpatrick. The London couple were set to perform their own interpretation of the jitterbug at the Grafton Rooms, having devised ‘a British version’ of the dance.

The Jitterbug on Trial

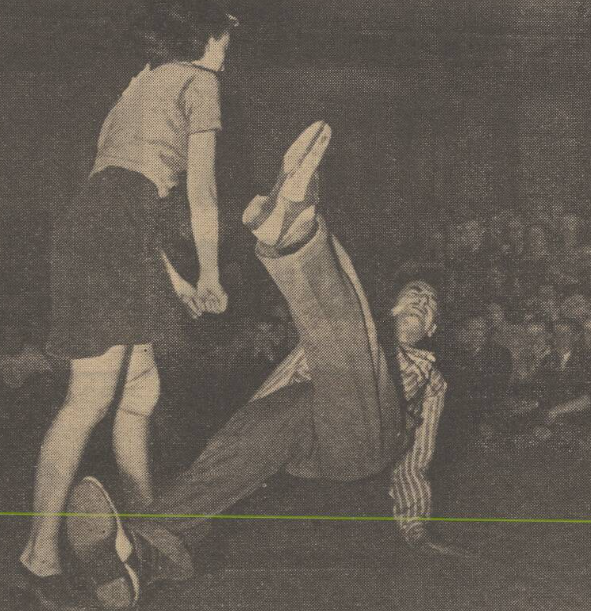

More negative publicity surrounding the jitterbug was to enter the pages of the Liverpool Echo in May 1940, this time in relation to the tragic death of nineteen-year-old Virginia Guidotti, from Brockley, London. Virginia had passed away whilst doing the jitterbug at a London palais de danse, with the dance later being performed at the inquest into her death.

Her jitterbug partner that night, Henry George Cox, was called to the stand. He explained that during the course of the evening he and Virginia, whom he had only met that night, had done ‘all kinds of fantastic and funny things’ whilst they danced together. He then proceeded to demonstrate the jitterbug to the coroner.

During the dance, however, Virginia had fallen backwards, with Cox falling on top of her. And whilst poor Virginia’s actual cause of death was deemed to be due to tubercular meningitis, the coroner pronounced that the jitterbug sounded ‘very vulgar’ to him.

The jitterbug had been on trial, and it was found to be morally bankrupt, and even dangerous. Indeed, the management at the palais de danse where Virginia and Cox had danced had apparently ‘made efforts to stop the dance being performed.’

The Jitterbug Epidemic

Despite such fears, the jitterbug craze continued to spread. In October 1940 Belfast paper Ireland’s Saturday Night reacted to an assertion that ‘Belfast lads and lasses were not the type to succumb to the jitterbug epidemic which has made bear gardens of the English ballrooms.’

This was disputed by the publication, who nevertheless observed how ‘the average Ulster jitterbug is a mere beginner at the game.’

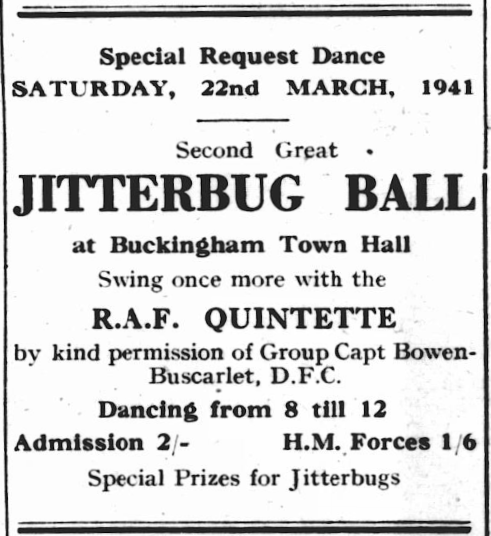

As the months rolled on into 1941, again some months before American troops arrived on British shores, evidence of the so-called ‘jitterbug epidemic’ can be found in our newspapers. Home county newspaper the Buckingham Advertiser and Free Press on 22 March 1941 advertised the ‘Second Great Jitterbug Ball’ that was to be held at the Buckingham Town Hall, accompanied by an R.A.F. quintette. Meanwhile Stirling, in central Scotland, hosted its own ‘Jitterbug Competition,’ this time in the open air, in July 1942.

Local paper the Stirling Observer described how 3,000 people came to watch the competition at King’s Park. In the event, only three couples participated in the well-attended event, all coming from different backgrounds. The competitors were James Watt, a father from Stirling, and his thirteen-year-old daughter Janet, Mr. W. Mentieth, a ‘strapping young fellow’ from Stirling and his partner, an ‘A.T.S. girl in tennis shorts and blouse,’ Miss M. Kean, and finally soldier Driver Tree and his partner L.A.C.W. Ross of the W.A.A.F.

This Stirling competition took place some months after the arrival of U.S. soldiers in the United Kingdom, but none of these competitors, at least, hailed from across the pond. In the end, the judge of the dancing, ‘jitterbug expert’ James Bayne of Stirling, awarded ‘the couples first equal,’ his decision being ‘loudly applauded.’

Check on Jitterbugging

Still, there was much to be done around the image of jitterbug dancing. Its general association with low moral conduct is evident through the reporting of the day. For example, Kent newspaper the Thanet Advertiser on 16 March 1943 printed the headline ‘Jitterbug Mad Girl Remanded in Prison.’ The following article reported on the ‘bad behaviour’ of a fourteen-year-old girl at a remand home. Alongside her other failings of being ‘an inveterate liar and a bad influence,’ she was accused of being ‘jitterbug mad.’

The association between bad behaviour and the jitterbug is a clear one. As for the unnamed fourteen-year-old girl, she was sent to Holloway Prison ‘until a vacancy occurs for her in an approved school.’

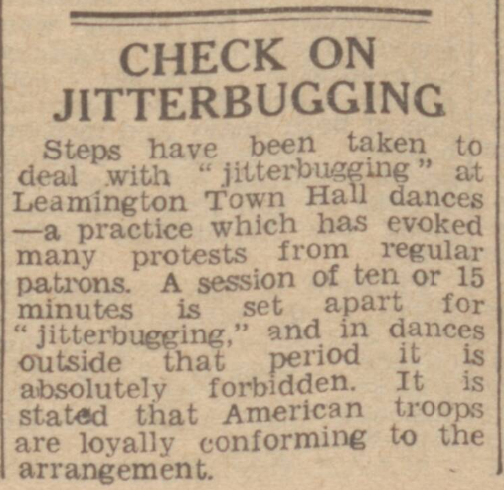

More formal methods of controlling the jitterbug craze were also being employed in Britain’s dance halls. On 29 September 1944 Midlands newspaper the Coventry Evening Telegraph reported how:

Steps have been taken to deal with ‘jitterbugging’ at Leamington Town Hall dances – a practice which has evoked many protests from regular patrons. A session of ten or 15 minutes is set apart for ‘jitterbugging,’ and in dances outside that period it is absolutely forbidden. It is stated that American troops are loyally conforming to the arrangement.

Enter the Americans, who are praised here for their compliance.

‘This Awful Habit’

Nevertheless, as the war ended, the jitterbug was still viewed in a negative light. In March 1946 national newspaper the Daily News reported on a meeting of ballroom proprietors and dancing teachers in Birmingham. There, Derby-based Mr. S. Ramsden expressed his dismay over the jitterbug:

‘We are determined to stop this awful habit…During the war, in spite of a deputation from American Army G.H.Q., I refused to tolerate jitterbugging in my ballroom…We are now having a boom in dancing and I appeal to you – lead our young people back to the stately dances of Old England.’

With wry amusement, the Daily News notes how his audience was in agreement, those ‘stately dances of Old England’ being those other foreign imports of the waltz, the minuet, and the like.

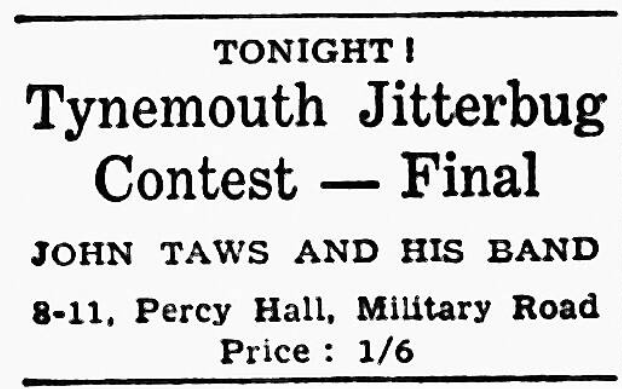

Despite the indignation of Mr. Ramsden and his apostles, by 1946 the jitterbug was firmly established in Britain. In March 1946 north east of England newspaper the Shields Daily News advertised the ‘Tynemouth Jitterbug Competition,’ whilst across the Pennines in June 1946 the Burnley Express promoted a ‘Grand Jitterbug Competition‘ to be held at the Mechanics’ Institute, just a few examples of many such jitterbug events.

Such advertisements fly in the face of other observations at the time, including this opinion that was aired by the Essex Newsman in July 1946:

Boogie-woogie, jiving, and jitter-bugging are innovations from America; very popular at one time when the U.S. troops were here. But all these fantastic gyrations are now disappearing gradually and at most ballroom dances are frowned upon.

War on Jitterbugging

The war may have been over, and American troops departed from British soil, but in August 1946 Sussex newspaper the Eastbourne Chronicle was reporting on a ‘War on Jitterbugging.’ This article appeared in response to the increase in popularity of the dance at Eastbourne’s Winter Gardens, where thanks to the music of Billy Forrest and his band, ’jitterbugging [had] increased to very large extent.’ Such couples proved to be an annoyance to those other patrons of the Winter Gardens, as a Chronicle reporter related:

‘I danced round the floor a number of times and found it very difficult and almost tiring to keep out of the way of the jive Kings and Queens, and I was pretty thankful when the music stopped.’

Meanwhile, a letter writer going by the moniker of ‘Anti-Jitterbug’ wrote to the Eastbourne Chronicle, expressing their dissatisfaction at the condition of Eastbourne’s dancefloors:

As one who frequents the Winter Gardens for dancing on two or three occasions a week, may I appeal to the management to prohibit the so-called ‘Jitterbug’ dances. In almost every dance, a small (but very lively) crowd get together on the floor and throw themselves about in all manner of contortions. This is all very disconcerting to the legitimate dancers and causes a great deal of unpleasantness as these ‘jazz-wonders’ are continually bumping into normal dancers making it a burden instead of a pleasure to go on the floor.

The letter writer observed how the jitterbug had been banned at ‘a well-known Brighton dance hall,’ just along the coast, suggesting how the ‘so-called dancers…dance to their hearts’ content in their own houses.’

The Eastbourne Chronicle took this indignant letter to Mr. G.H. Hill, the Entertainments Manager at the Winter Gardens. He told the paper how the ‘jitterbug question had been worrying him for some time,’ and he had made efforts to create separate sessions for those who wanted to indulge in the dance. As far as the Eastbourne Chronicle was concerned these steps appeared to be working, as at ‘Thursday night’s dance ‘jitterbugging’ was confined to special sessions, and when other dance numbers were played Billy Forrest, the band leader, reminded the crowd that only ordinary dancing would be allowed.’ Most, but not quite all, couples complied.

The Jitterbug is Dying Out

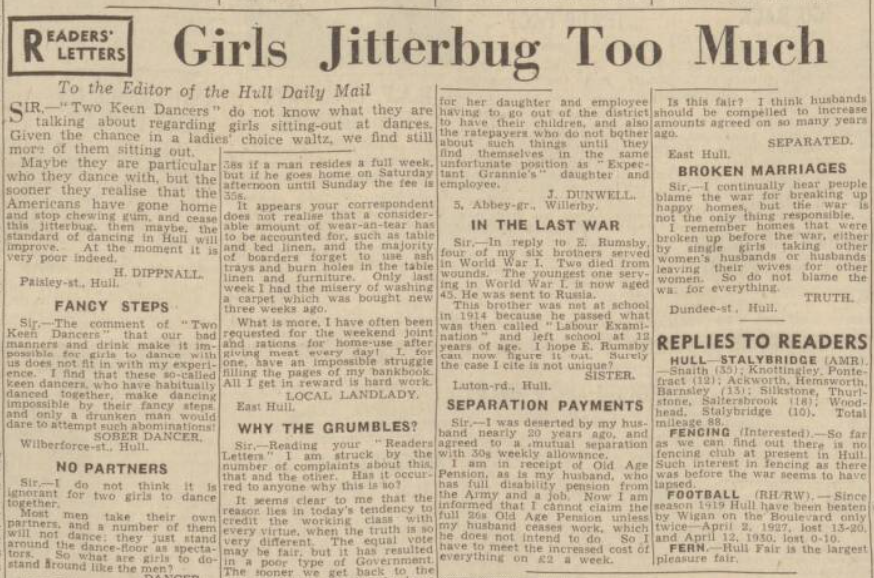

Another disgruntled letter writer this time addressed Yorkshire paper the Hull Daily Mail in October 1946 to criticising the quality of dancing in Hull. This had a lot to do with the jitterbug, as correspondent H. Dippnall, in response to a previous letter, explains:

‘Two Keen Dancers’ do not know what they are talking about regarding girls sitting-out at dances. Given the chance in a ladies’ choice waltz, we still find more of them sitting out. Maybe they are particular who they dance with, but the sooner they realise that the Americans have gone home and stop chewing gum, and cease this jitterbug, then maybe, the standard of dancing in Hull will improve. At the moment it is very poor indeed.

H. Dippnall was part of that school of thought which appended the jitterbug to a vulgar kind of Americanism, as did journalist Charles Graves. In an article for illustrated weekly paper The Sphere, Graves described the boom in dancing that followed the end of the Second World War. But the jitterbug, at least in Graves’s mind, was not included in such a renaissance:

In the meantime, I am glad to be able to report that jitterbugging is dying out fast. It was an alien importation of the American soldier and proved a great nuisance because members of the public who were doing proper ballroom dancing were impeded by these semi-stationary jivers.

They Still Carried On

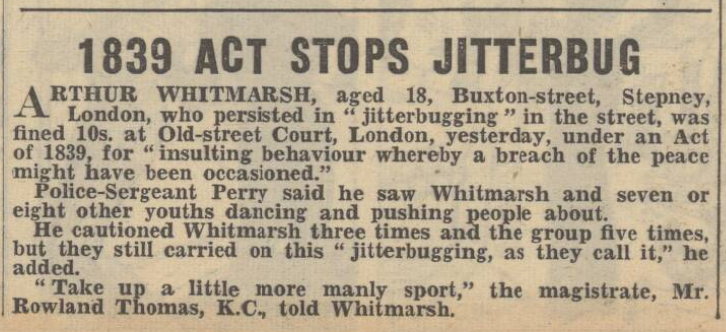

But was the jitterbug really dying? In March 1947 national newspaper the Daily Mirror was reporting on the jitterbug being performed in the streets. Eighteen-year-old Arthur Whitmarsh from Stepney was fined after he had ‘persisted in jitterbugging in the street.’ Who knew that the jitterbug could be deemed as illegal? The Daily Mirror explained how Whitmarsh had been fined thanks to an Act of 1839, for ‘insulting behaviour whereby a breach of the peace might have been occasioned.’

It wasn’t just Whitmarsh who was caught jitterbugging on the streets of London. He was accompanied by ‘seven or eight other youths’ in his dancing exploits. Not only is this article testament to the continuing popularity that the jitterbug was enjoying, but also to the continuation of its positioning as a morally dangerous pursuit.

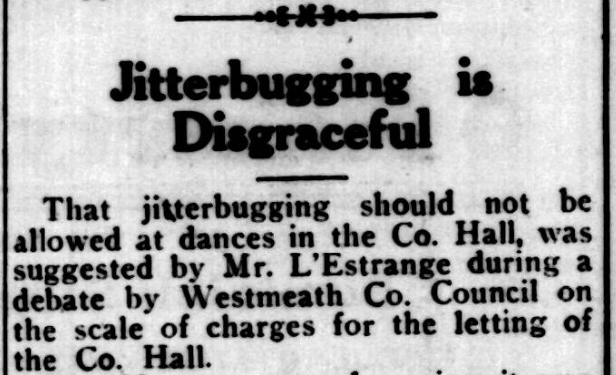

And still, by the end of the decade, the jitterbug question continued to divide. In Ireland in 1949 the East Galway Democrat reported how it was proposed that the jitterbug should not be performed in Westmeath County Hall. The man behind this motion, Mr. L’Estrange, described the dance as ‘disgraceful,’ relating how it had been banned in ‘Dublin halls.’

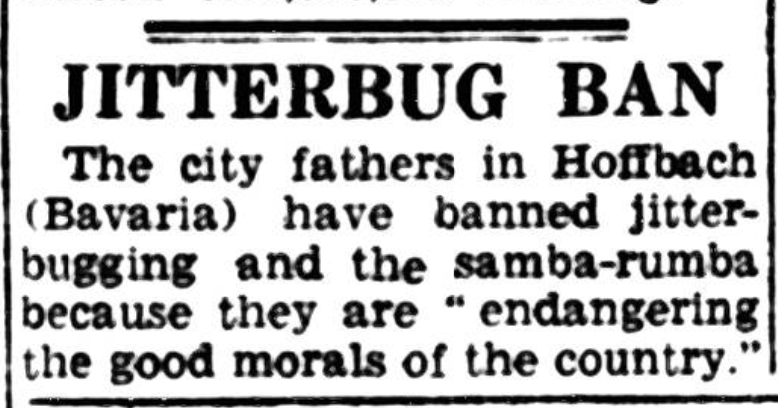

The jitterbug also faced a ban further afield, the Coventry Evening Telegraph on 17 November 1949 reporting how ‘the city fathers in Hoffbach (Bavaria) have banned jitterbugging and the samba-rumba because they are ‘endangering the good morals of the country.’’

Bad moral influence, or exciting new trend, the jitterbug certainly took the United Kingdom by storm in the 1940s. Find out more about this eventful decade, the history of dance, and much more besides, in the pages of our Archive today.