The murder of 21-year-old actress Eileen Isabella Ronnie Gibson, who went by the name stage name of Gay Gibson, whilst she was travelling home from South Africa aboard the Durban Castle, in October 1947, made headlines across Britain and the world.

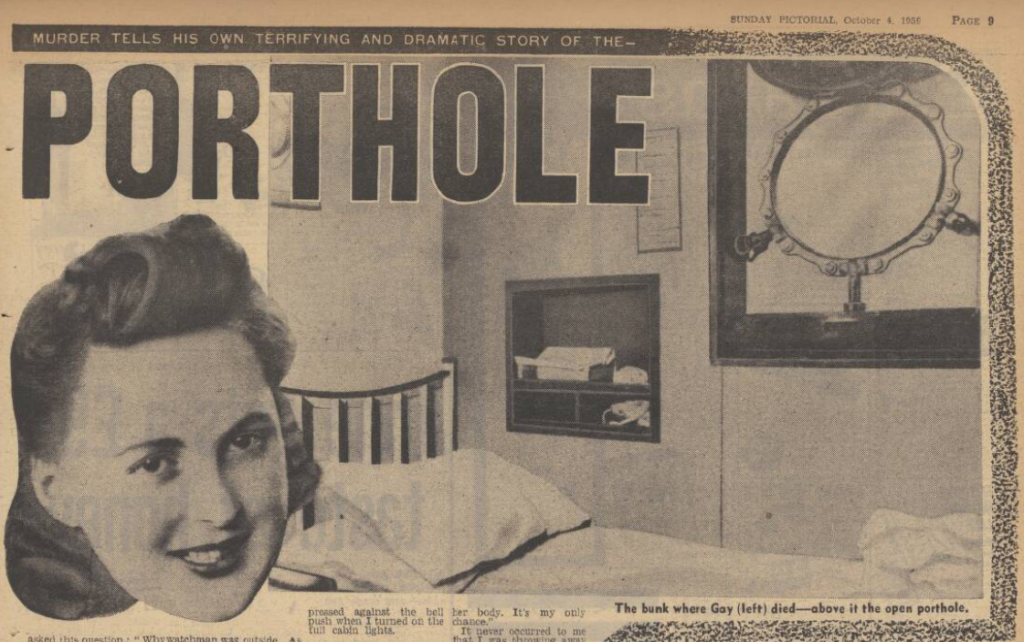

Also known as the ‘Porthole Murder,’ thanks to the method in which Gay’s body was disposed, the case gained notoriety due to its parallels with film noir and popular fiction penned by Agatha Christie.

In part one of a series of special blogs, using newspapers from the time, we will take a look at the murder of Gay Gibson. We will try to understand more about the young actress who lost her life, whilst endeavouring to learn what exactly took place in the early hours of 18 October 1947 aboard the Durban Castle.

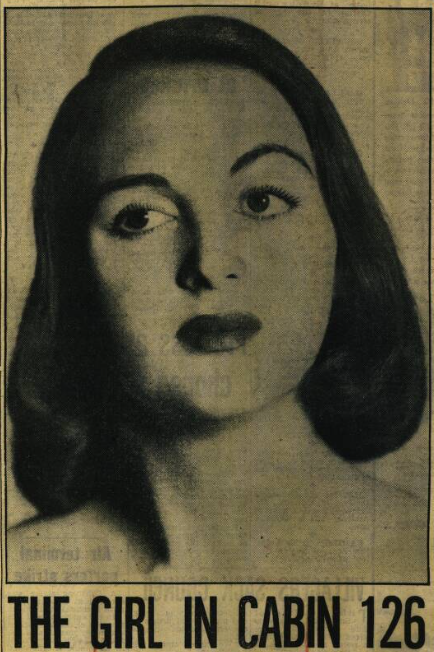

The Girl in Cabin 126

On 26 October 1947 news of ‘The Girl in Cabin 126‘ hit the front page of national Sunday newspaper the Sunday Pictorial, which would later become the Sunday Mirror. Complete with a large photograph of Eileen ‘Gay’ Gibson, the article reported how:

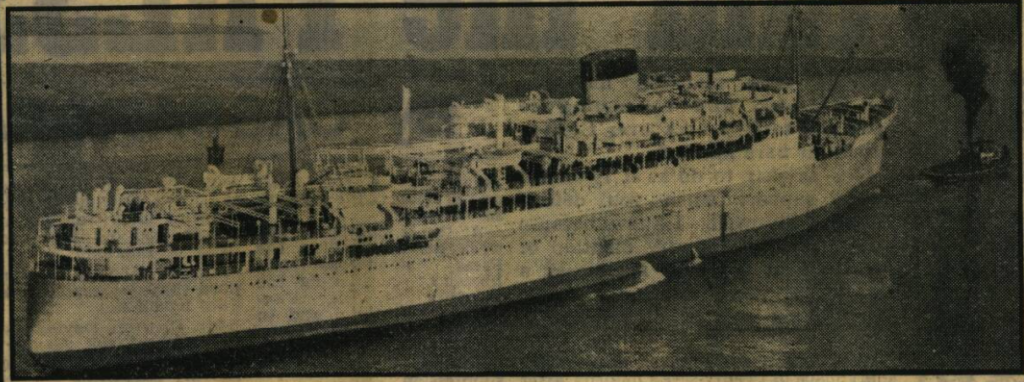

Last night C.I.D. men were working on clues from Cabin 126 on the liner Durban Castle, from which pretty, red-headed Eileen (Gay) Gibson, 21, London, actress, disappeared on the homeward voyage, from South Africa.

It seems, at least during these early stages, as the Durban Castle arrived in Southampton, that the circumstances of Gay Gibson’s disappearance were unknown to the press. However, it was reported that she had been seen ‘dancing happily at midnight with other first-class passengers,’ whilst the Sunday Pictorial related how police had ‘asked their opposite numbers and coastguards at Freetown (Sierra Leone) to cover the possibility of the body being washed ashore.’

The Durban Castle had been ‘steaming at seventeen knots just south of Freetown’ when Gibson had disappeared ‘in the early morning of October 18.’

Meanwhile, on 27 October 1947, the Daily Herald reported how ‘all shipping and aircraft passing ‘Position X,’ 270 miles off the West Coast of Africa, are keeping a look-out for a 21-year-old girl’s body in black pyjamas.’ This effort extended across the countries of Liberia, Sierra Leone and Senegal, but all efforts were in vain, as Gay Gibson’s body would never be recovered.

The ‘Cherry-Blonde’ Actress

But just who was the ”cherry-blonde’ actress‘ Gay Gibson? The London’s Daily News had this to say on 23 March 1948:

When the war broke out Eileen Gay Gibson was a schoolgirl of 13 ½. Born in India, she was brought up in Birkenhead until in 1940 she joined her mining engineer father, mother and brothers in Persia. Little more than a year later she joined the A.T.S. It was in February, 1947, that she left Birkenhead for the last time to join Joseph Basnett Gibson, her father, her mother and brothers in Durban.

It was during her spell in the A.T.S.’s (Auxiliary Territorial Service) entertainment branch that Gibson entered the acting world. Years later, writer Denis Herbstein would elaborate on Gay Gibson’s career in the pages of The Stage magazine:

Miss Gibson, aged 21, was an actress from Liverpool who had joined the ATS in 1944 and was in ‘Stars in Battledress,’ in this country and on the Rhine. In early 1946 she toured England in ‘The Man with a Head for a Mischief’, and later played in ‘Jane Steps Out.‘

Whilst in South Africa, Gay Gibson would again take to the stage, with her last months reported on in the newspapers as part of the trial of her killer.

South Africa

Between February and October 1947 Gay Gibson toured South Africa. Insight into this time was provided by fellow actor Mike Abel, whose evidence was part of the defence’s case at the trial of Gibson’s murderer. According to the Sunday Pictorial on 21 March 1948, Abel had ‘been alone with her on several occasions,’ as he stated from the witness stand:

‘On one occasion we were sitting in the car at a roadhouse when she seemed to lurch over on my side. I noticed the corners of her mouth all white and her lips were a blueish colour.’

Such testimony fuelled the suspicions that Gay Gibson was in poor health, something we shall see the defence leaning on heavily in their case. Abel’s accounts, meanwhile, also provided insight into Gibson’s mental state. He described how she would cry for ‘no reason at all’ at rehearsals, whilst also recounting how she had once expressed her love for him. Abel, a married man, had rebuffed her.

Perhaps most startingly of all, he claimed how:

‘On one occasion she asked me for £200 to go to England to get a doctor to take care of her. She said she was pregnant. I said to her: ‘Who got you into this trouble?’ She didn’t tell me, but just laughed it off.’

Such tales swirled around the character of Gay Gibson. Indeed, whilst her murderer went on trial, her character too went on trial, condemned as a loose, morally corrupt, young woman. Gay Gibson, missing and disappeared, was unable to defend herself, with only the clues left behind in her cabin and the words of others as her defence.

On Board Ship

Gay Gibson would eventually travel to England, the Yorkshire Evening Post on 18 March 1947 describing how the young actress embarked at Cape Town ‘in October last to return to England.’

What was Gay like on board ship? Evidence was given at trial by one of her Durban Castle table mates, Frank William Montagu Hopwood, who just happened to be an official from the Union Castle Line, the owners of the ship.

The Daily Mirror on 19 March 1947 reported how Hopwood stated that Gay Gibson seemed ‘generally depressed at times but she improved later.’ He told of how she had ‘two or three drinks’ every night, and although she ‘was easy to get on with…she declined to speak about her public life.’ She also had ‘no young men friends on the boat.’

Most importantly, it was Hopwood who used to ‘take her down’ to her cabin every night, and he was with her on her ‘last night,’ as the Yorkshire Evening Post details:

On the last night of her life Miss Gibson dined with her two table mates, a Mr. Hopwood and a Wing-Commander Bray. At about 12.40 a.m. Mr. Hopwood took her down to her cabin and said good-night to her. She was wearing a black evening frock.

The Night of 17 October 1947

What happened next, during the evening of 17 October and the early hours of 18 October 1947 on board the Durban Castle as it sailed off the west coast of Africa, would be the subject of extensive investigation and conjecture. From our newspapers, we have pieced together a timeline of events leading to the disappearance of Gay Gibson.

From our earlier reports, we learn that Gay Gibson was dancing at midnight, and then taken to her room by Frank Hopwood at 12.40am. However, an account from deck steward James Camb, who would later go on trial for her murder, put Gay somewhere else at 11pm on the evening before her death.

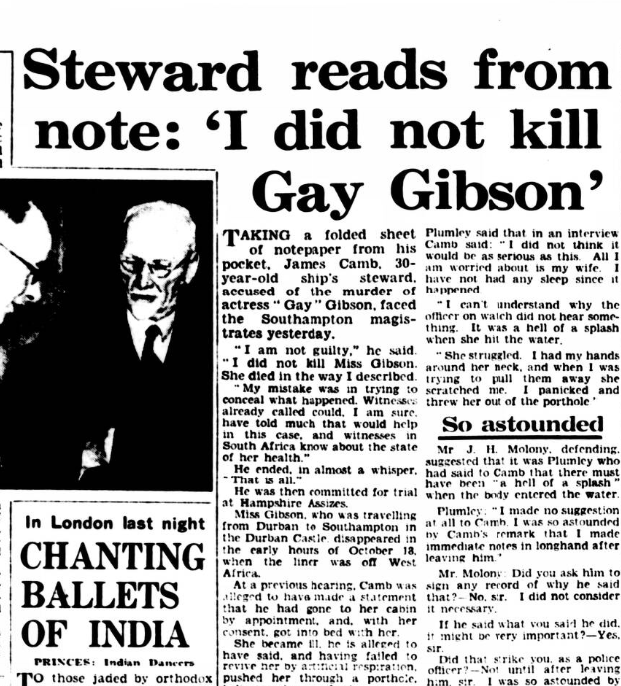

In an interview with Southampton police’s Detective-Sergeant Quinlan, as told at the Southampton magistrates’ hearing into Gay’s disappearance and related by the Daily Herald on 25 November 1947, James Camb said:

‘I want to tell you something. I did not want to tell you in front of Mr. Turner (a Union Castle inquiry officer), as I had no right to go to her cabin, but I did go about 11 o’clock that night to ask her if she wanted some lemonade with her rum.’

At this meeting at 11pm on 17 October 1947, as told at the subsequent trial of Camb in March 1948 and reported by the Yorkshire Evening Post, Camb ‘made an appointment to meet’ Gay ‘that night.’

The Early Hours of 18 October 1947

Now, as related by the Daily Herald and as told by James Camb, Gay Gibson collected the glass of rum he had left for her ‘on a ledge outside the pantry…just before one o’clock.’ Camb then went ‘to the well deck and had a smoke before turning in.’

At the trial, as reported by the Yorkshire Evening Post, Gibson was then seen at ‘1 o’clock…by a bosun’s mate, Conway, standing by the rail in a black frock, smoking a cigarette.’ Prosecutor Mr Roberts observed how:

‘Conway is the last person except the prisoner who is known to have seen the girl alive or seen her at all.’

Interestingly, Detective-Sergeant Quinlan asked James Camb whether ‘Miss Gibson [was] in the habit of being on deck late at night unaccompanied. Camb replied that he had seen her on deck alone before, and explained how he had once seen her with a ‘clock in her hand.’ This strange detail was never explained.

This is where the timeline varies slightly. The Daily Mirror on 19 March 1948, reporting on the trial, has it that James Camb went to Gay Gibson’s cabin ‘at two o’clock,’ when ‘intimacy took place.’ According to Detective-Sergeant Quinlan, alongside other accounts, Camb ‘had been in Miss Gibson’s cabin about 3am on October 18.’

As for what happened in the cabin, we only have Camb’s account. Here it is, in all its starkness, as reported by the Daily Mirror:

‘After a short conversation I got into bed with her consent. Intimacy took place…She suddenly clutched at me, foaming at the mouth. She was very still. After a struggle with the limp body – by the way she was still wearing her dressing gown – I managed to lift her to the porthole and pushed her through.’

Bells at 3am

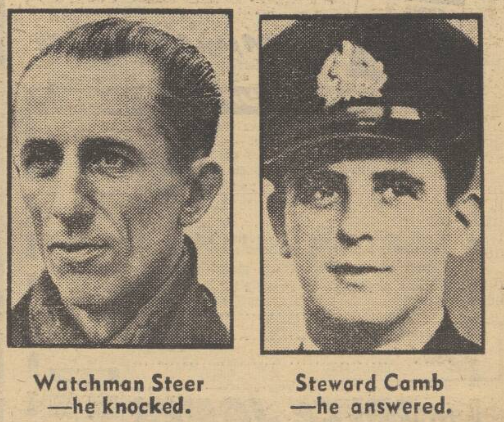

The first sense that anything was wrong in Cabin 126 was when an alert was received at just before 3am. Someone had rung the cabin bells, and the call was responded to by Frederick Dennis Steer, a watchman.

This is how Mr Roberts for the prosecution described what happened, as related by the Yorkshire Evening Post in March 1948:

‘Shortly before three o’clock, in response to the ringing of indicators, a watchman named Steer went to Miss Gibson’s cabin, where the indicators showed the button for the steward and stewardess had been pushed. The light was on, but there was no answer to his knock, and when he opened the door he saw Camb standing in the cabin, wearing a singlet and trousers.’

Frederick Steer later told the court at Camb’s trial:

‘I opened the door about a couple of inches, and the door was shut in my face by a man’s right hand.’

According to the Yorkshire Evening Post Camb said ‘all right’ to Steer, and ‘there was not a sign of the girl.’ Then, ‘ten minutes later the light in the cabin went out.’ Gay Gibson was never seen again.

Click here to read the second part of our blog series on the murder of Gay Gibson, which will look at what happened when she was discovered missing, and how James Camb was accused of her causing her death.

Discover more about Gay Gibson, crime history, and much more besides, in the pages of our newspaper Archive today.