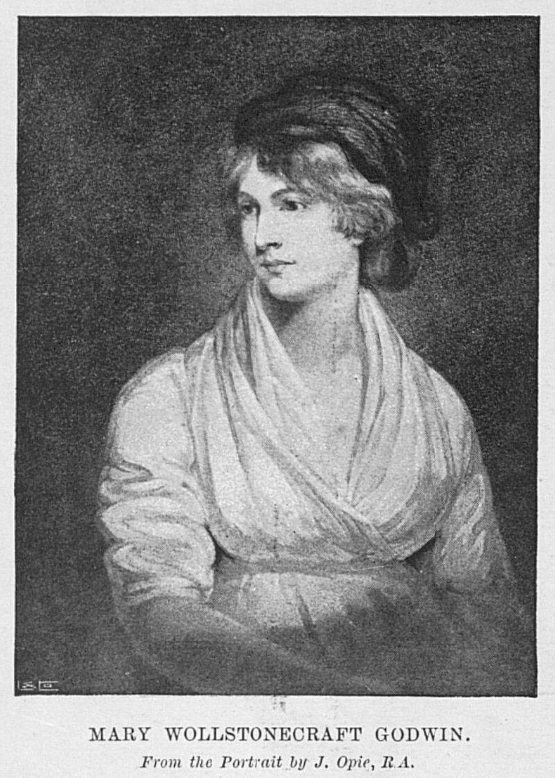

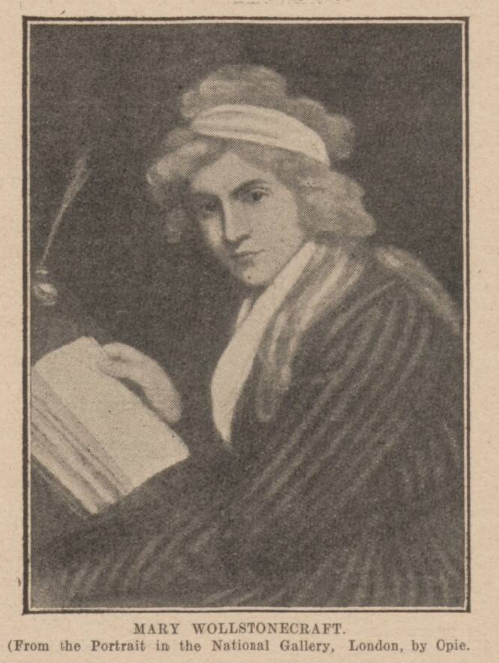

Eighteenth century writer and philosopher Mary Wollstonecraft was an early advocate of women’s rights. Lambasted during her lifetime for her refusal to conform to societal norms, she is seen today as one of the first feminist philosophers.

In part one of our special blog series, we will examine the life of Mary Wollstonecraft, using newspapers found in our Archive. We will trace her life from its early difficulties, through to the publication of her trailblazing novels and pamphlets, learning how she was condemned and censured by the press of the time.

Register now and explore the Archive

‘Great and Unmerited Harshness’

Mary Wollstonecraft was born on 27 April 1759 in Spitalfields, London. Her grandfather was a rich manufacturer, but her early life was a difficult one. A near-contemporary account of her life, published by the The Scots Magazine in May 1798 in response to her husband William Godwin’s publication of the Memoirs of Mrs Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin, explains how she ‘was treated in her infancy with great and unmerited harshness and severity by her parents, who appear to have been ill qualified for the business of educating their children. ‘

Meanwhile, over hundred years later, M.E. Ridler writing for women’s suffrage publication the Vote in September 1910 describes how:

Mary Wollstonecraft’s girlhood was passed amidst scenes of domestic tragedy. Her father – a spendthrift and hard drinker – was a man of ungovernable temper, who not only ruined the family fortunes, but cruelly ill-treated the mother, whom Mary loved with all the strength of a passionate nature, and of whom she became the self-constituted protector.

The Scots Magazine | 1 May 1798

Forced to support both herself and her siblings, Mary Wollstonecraft had to find work. M.E. Ridler goes on to relate how:

The chief occupations then open to single women having no male relative upon whom to depend were those of companion and governess; and Mary Wollstonecraft, from the age of nineteen to twenty-eight, was engaged in these uncongenial pursuits, at the same time being harassed by continual appeals for assistance from her two sisters and younger brothers.

The enterprising Mary, as Arthur Hayden, in piece marking the centenary of her death for The Sketch in September 1897, ‘set up a little school in Newington Green, which kept its doors open for two years.’ Her life, and the lives of those around her were, however, marked by tragedy.

Thoughts on the Education of Daughters

As Arthur Hayden for The Sketch outlines, ‘a terrible fate seemed ever to pursue the members of Mary Wollstonecraft’s family.’ Her sister Eliza was so ‘ill-treated’ by her husband, that ‘she had to flee from him and place herself in hiding till a legal separation could be obtained.’ Eliza’s experience, however, and the experience of women like her, would inspire Mary’s unfinished novel the Wrongs of Women.

After having opened the school in Newington Green, Mary’s close friend Fanny Blood fell sick. Fanny was living with her husband in Lisbon at the time, and Mary travelled to ‘nurse’ her friend there. But as Arthur Hayden relates, ‘she arrived too late.’

Travelling back to England, the The Scots Magazine describes both how ‘the school in her absence had suffered considerably,’ and how Fanny Blood’s bereaved parents ‘wished to transport themselves to Ireland.’ It was then, in 1787, that Mary Wollstonecraft penned her Thoughts on the Education of Daughters, which was published by Joseph Johnson and offered advice on the education of women to the British middle classes.

The Scots Magazine tells of how she sold the pamphlet for ten guineas, enabling her ‘to effect the purpose for which it was secured,’ namely helping her deceased friend’s parents leave England. Next, Mary ‘accepted the office of governess to the daughters of Lord Viscount Kingsborough.’ The Scots Magazine scathingly describes how ‘wonders [were] told of the salutary effects of her system of education’ whilst in this position, although Arthur Hayden has it that ‘she was dismissed after a year by [Lord Kingsborough’s] wife, who was jealous of the children’s affection for their governess.’

It was during her time with the Kingsboroughs that Mary Wollstonecraft, as related by the The Scots Magazine, penned Mary: A Fiction. This novel was largely inspired by her relationship with Fanny, and her next work would come to be her most well known.

A Vindication of the Rights of Women

As the The Scots Magazine explains, Mary Wollstonecraft wrote her 1790 work the Vindication of the Rights of Men in response to Edmund Burke’s Reflections on the Revolution in France. Whilst Burke looked to defend the status quo of the monarchy and the Church of England, Wollstonecraft attacked both. Then, in 1792, she would publish A Vindication of the Rights of Women.

This seminal work would argue that women were deserving of the same rights as men. As women’s suffrage paper the Common Cause would describe in December 1920, A Vindication of the Rights of Women was ‘the first time that such a protest, such a claim, had been put forward.’ Consequently, Mary Wollstonecraft suffered the indignation of the nation, M.E. Ridler writing over 100 years later how:

The publication of Mary Wollstonecraft’s book in 1792 brought down upon the head of the courageous author an unprecedented avalanche of obloquy and scorn. That ‘this hyena in petticoats,’ ‘this philosophising serpent’ (as Horace Walpole designated her) – should be guilty of such an indelicacy as to write at all was bad enough, but that she should use her pen to attack the very foundations upon which the scared superiority of man had, throughout generations, been painfully built up was an unforgivable offence, and that the writer should prove the sincerity of her convictions by putting into practice the theories she so enthusiastically advocated was to place herself entirely outside the pale of society.

Indeed, Wollstonecraft has been deemed by many as ‘far in advance in her time,’ as she outlined a ‘system of co-education under which boys and girls, side-by-side, should, in addition to the three R’s, study mechanics, botany, and the sciences.’ Furthermore, she looked forward to when ‘women would be allowed to work any art, craft or profession for which they were fitted, and when women equally with men would receive an adequate recompense for their labour.’

Wollstonecraft, furthermore, as M.E. Ridler describes, highlighted the ‘fallacy of the idea that the sole aim and end of woman is to make herself agreeable and pleasing to man.’ However, it was to be her lifestyle that was to gain for her further infamy and scorn during her own lifetime.

‘A Vulgar Sensualist’

The Scots Magazine piece from 1798 picks up the next phase of Mary Wollstonecraft’s life, its condemnation of her choices and beliefs clearly evidenced. It relates how Mary ‘proceeded in her anti-religious plan of independence on systems with great rapidity,’ whilst also telling of how she, ‘at the age of more than 30 years…divested herself of that old fashioned prejudice,’ that prejudice being her chastity.

That a national publication would choose to report on a woman’s loss of virginity seems unbelievable to us, but at the time, aside from the publication of her radical early feminist works, Mary’s desertion of the sexual status quo was her greatest misstep, at least in the eyes of her contemporaries. That she refused the confines of marriage, to pursue her own pleasure, not only made her a fallen woman, but a dangerous one too.

As the The Scots Magazine outlines, Mary Wollstonecraft had formed, in the words of her future husband William Godwin, a ‘perfect and ardent affection’ for the Swiss painter Henry Fuseli. This affection not being reciprocated, she travelled to Paris in December 1792, where she ‘deliberately entered (as Mr Godwin expresses it) into that species of connection, for which her heart secretly pained.’

This was a sexual connection with American adventurer and ‘vulgar sensualist’ Gilbert Imlay, with whom Arthur Hayden delicately describes for The Sketch ‘she agreed to live with as a wife.’ The Scots Magazine puts the relationship under a lascivious microscope, as it ‘marks the time of the consummation of this intrigue to… the middle of April 1793.’

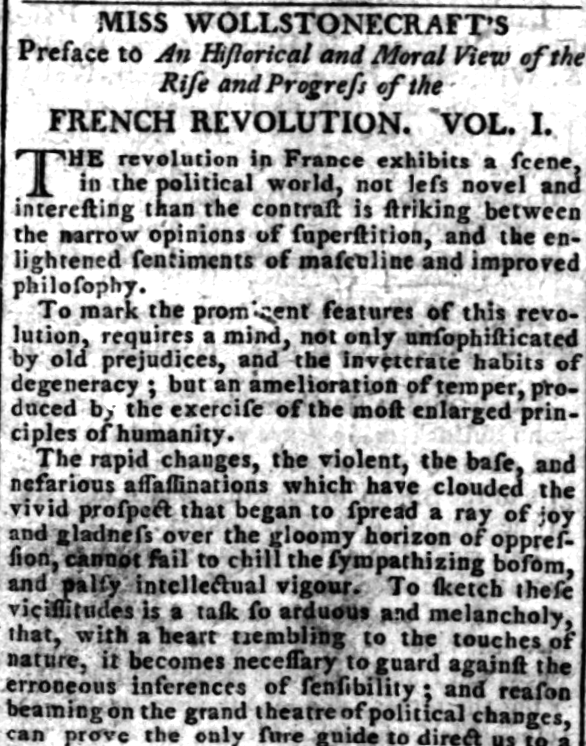

Mary’s first daughter Fanny Imlay was born in 1794, and after that, as the The Scots Magazine relates, Imlay grew ‘negligent and indifferent towards’ the mother of his child. Mary Wollstonecraft, meanwhile, continued to write, penning An Historical and Moral View of the French Revolution in the same year.

Arthur Hayden picks up the narrative of Mary’s life, describing how:

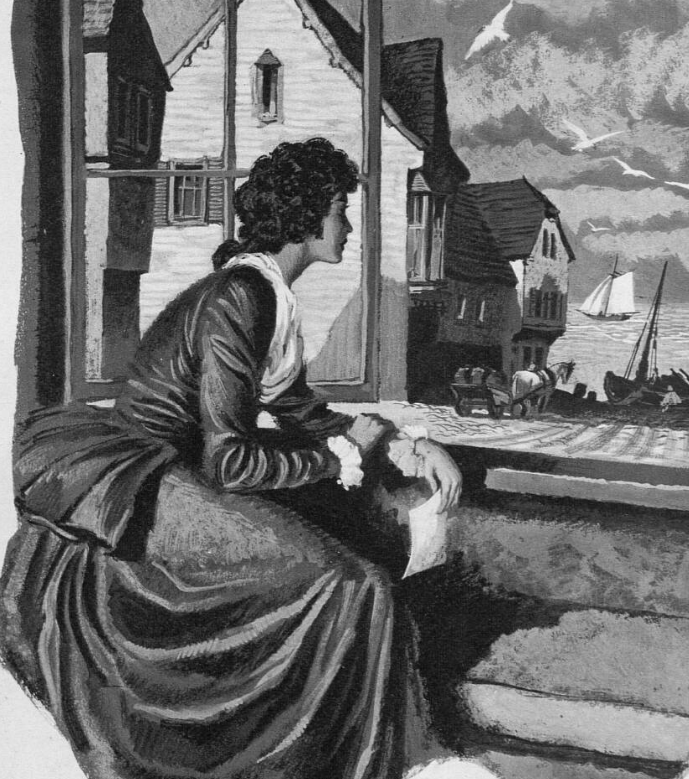

She came to England with Imlay in 1795, and in June the same year she sailed to Norway, to make the arrangements for some of Imlay’s commercial speculations. A volume of letters descriptive of that visit she afterwards published in 1796.

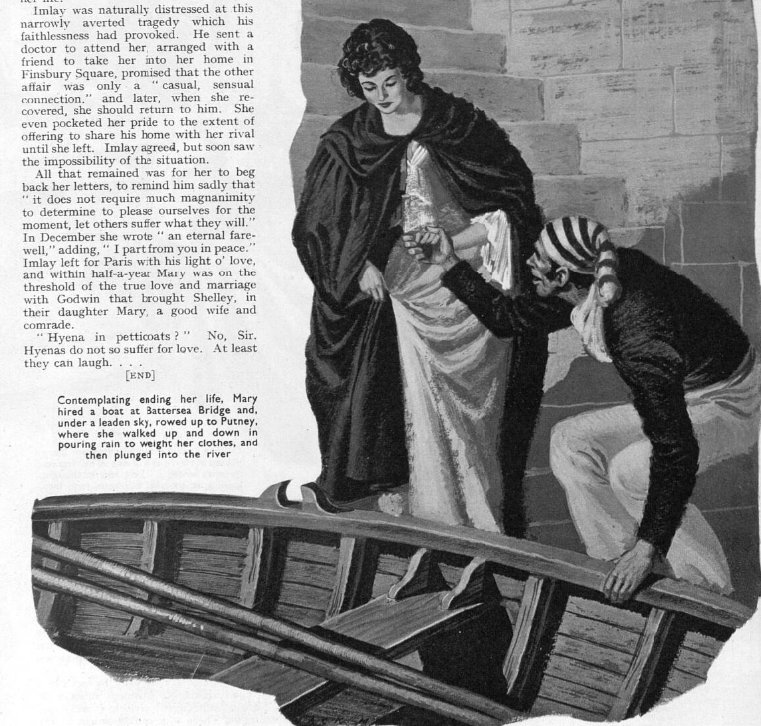

It was then that Mary Wollstonecraft faced one of the greatest difficulties in her life, the discovery that that Imlay had been unfaithful. The Scots Magazine narrates this moment with some pathos, relating how she ‘would sooner suffer a thousand deaths, than pass another of equal misery,’ after the revelation of the father of her child’s infidelity. The piece goes on to narrate in vivid detail how Mary attempted to take her own life by jumping into the Thames at Putney Bridge. She was, however, saving by a passing boat.

Marriage and Death

Later in 1796, as Arthur Hayden relates, Mary Wollstonecraft would ‘form an alliance’ with writer and early anarchist William Godwin. The pair married in March 1797, and Hayden describes how:

Their domestic relations, taken altogether, were very happy. Godwin held peculiar views as to matrimonial life, as did Mary herself, and he lived twenty doors away from her, so that they might not weary of each other’s society – a very sensible arrangement for two philosophers.

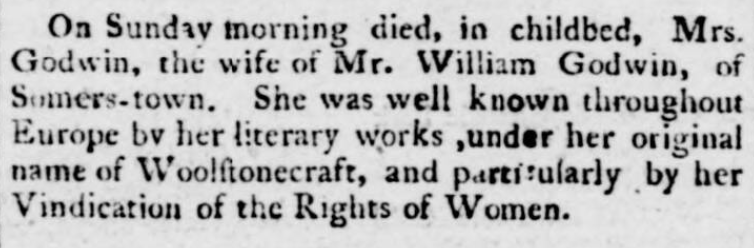

Sadly such happiness was to be short-lived, as ‘the birth of her child Mary was fatal to her, and she died on September 10, 1797.’ Her child, Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin, would go to pen the trailblazing science fiction work Frankenstein.

Even in her death Mary Wollstonecraft faced censure. The Scots Magazine was dismayed by the particulars of her death as related in William Godwin’s memoirs, labelling them as ‘disgusting.’ Even in her death, by the female act of giving birth, bringing life, Mary Wollstonecraft was too much of a woman for her age. This was not the only complaint of the publication surrounding her death:

She died on 10th of September, her husband boasts that during her whole illness not one word of a religious cast fell from her lips. Rare philosophy! On the 15th she was interred in the church-yard of St Pancras.

For The Scots Magazine, Mary Wollstonecraft’s short life served as a parable. She had acted beyond societal norms, only to pay a well-deserved price:

It may act, however, as a warning to those who fancy themselves at liberty to dispense with the laws of propriety and decency, and who suppose the possession of perverted talents will atone for deviations from rules long established for the well-government of society, and the happiness of mankind.

In our next blog we will examine, again using newspapers from The Archive, the legacy of Mary Wollstonecraft. We will look at how the outrage at her perceived immorality began to be outweighed by admiration for her pioneering early feminist works, and how she was transformed into an important figurehead for the women’s suffrage movement in Britain in the early 20th century.

1 comments On The Radical Life and Rare Philosophy of Mary Wollstonecraft

Thank you for sharing a very meaningful article, I think it will be very helpful for me and everyone.