A walk along Piccadilly in the black-out is one of the many queer experiences of this war. The once brilliant centre of London’s night life is now as dark as any forest, and indeed, like a forest, the darkness is full of rustlings and whisperings, of half-seen shapes, and of a sinister feeling of eager, but invisible, life.

Daily Herald | 26 April 1940

So began a Daily Herald article on blackout crime in London during the Second World War. With blackouts imposed across the United Kingdom in a bid to keep German bombers at bay, so came the opportunity for criminals to commit their dark deeds in almost perfect darkness. But did crime levels increase during the Second World War?

In this special blog, using our newspapers, we will investigate blackout crime in the United Kingdom during the Second World War. We will examine the early fears of a ‘blackout crime wave,’ and how by the first few months of the war, these concerns had begun to dissipate. We will also look at how violence was directed at women during the blackout, and explore the crimes of ‘Blackout Ripper‘ Gordon Frederick Cummins.

Register now and explore the Archive

The Blackout ‘Crime-Wave’

In the first few weeks of the war, on 21 September 1939, eminent Scottish newspaper The Scotsman was reporting on a ‘black-out ‘crime wave” in Edinburgh. The crime the newspaper was reporting on was that of house breaking, with unemployed labourers William Ross (20), Edward Munro (18), and David McGarry (24), all admitting to having broken into a house in Lady Lawson Street and stolen a suit. Ross and Munro had also stolen clothes from another house, as well as a cigarette machine, which contained 236 cigarettes, ‘from the doorway of a shop in Stockbridge.’

The prosecution was in no mood for sympathy for this crime; Mr Gray, the depute-fiscal, stated how ‘taking advantage of the black-out conditions makes it all the worse.’ Ross and Munro were sentenced to three months in prison, whilst McGarry received one month.

Meanwhile, crime was being committed at the other end of the United Kingdom, in Exeter, Devon. According to the Western Morning News, 27 September 1939, 29-year-old labourer John William Cotter had quite literally been caught in the act whilst ‘attempting to break and enter,’ in spite of the blackout conditions.

Prosecutor for the case Mr T.J.W. Templeman remarked how ‘the black-out makes crime very easy to commit, but quite difficult to find out,’ although this did not seem to be the case for Cotter. He had been discovered on Fore Street by a constable, ‘standing by the shop door, with a shoe in his left hand and his right hand thrust through a broken glass panel.’ Upon seeing the constable, the unlucky Cotter said: ‘I did not think you were around. I was told that this was an easy job, but I’ve come unstuck again.’

Meanwhile the Scottish press continued to fixate on the so-called ‘black-out crime wave,’ The Scotsman on 2 October 1939 reporting how:

There have been a considerable increase in the number of cases dealt with at Edinburgh Burgh Court since September 3. By comparison July and August were quiet.

For a short spell during September Edinburgh was hit by a black-out crime ‘wave’ which caused considerable perturbance. Shops in the Tollcross district were looted by smash-and-grab raiders, whose spoils included bicycles, tinned foods, jewellery, clothing, and other sundry articles, which were mostly recovered by the police, although some were in a damaged condition.

Indeed, in the early days of the war, it appeared that there had been an alarming rise in the amount of crimes being committed, and new types of offending were coming to the fore.

‘New Types of Offenders’

The Scotsman on 2 October 1939 detailed these ‘new types of offenders.’ These new types of offenders were those who infringed the defence regulations, for example, by showing a light from their homes during the blackout.

Others broke the law by hoarding items, with one motorist picked out by The Scotsman for ‘petrol hoarding.’

Meanwhile Northumberland’s Blyth News on 11 November 1939 highlighted ‘a new type of black-out’ crime being committed in the seaside town of Blyth. The newspaper notes how this crime reached ‘the lowest depths of meanness,’ outlining how it involved:

…the theft of plants from gardens with the idea of replanting them elsewhere. Victims of it include an elderly couple in Haughton Terrace, whose loss is a lavender bush they have tended with loving care for a number of years.

Other acts of ‘hooliganism’ had been ‘practised under the cover of darkness in certain areas of the town.’ Such acts included an ‘epidemic of gate-lifting,’ a spate of ‘stone-throwing,’ and the ‘particularly silly game of moving the sandbag barricading around telephone kiosks until the door was effectively barred against potential users of the call-box.’

‘Black-Out Crime Warning’

As already witnessed in Edinburgh, authorities were not predisposed to look kindly upon blackout offenders.

In pronouncing a sentence on labourer Edward Sidney Jones (32) for housebreaking and larceny at the Liverpool Assizes, Mr Justice Stable grandly proclaimed:

‘Woe betide the man who comes before me for breaking into a house or committing any crime of violence during the period of the black-out.’

As the Liverpool Daily Post on 19 December 1939 reported, Jones ‘asked for an opportunity to join the army,’ promising the judge that he ‘would not let him down.’ But Jones’s card had been marked; he was the worst type of criminal in society’s eyes, a blackout criminal, and the judge turned him down. In a stinging rebuke, Mr Justice Stable responded by stating how ‘too much public time and public money had been wasted on him already.’

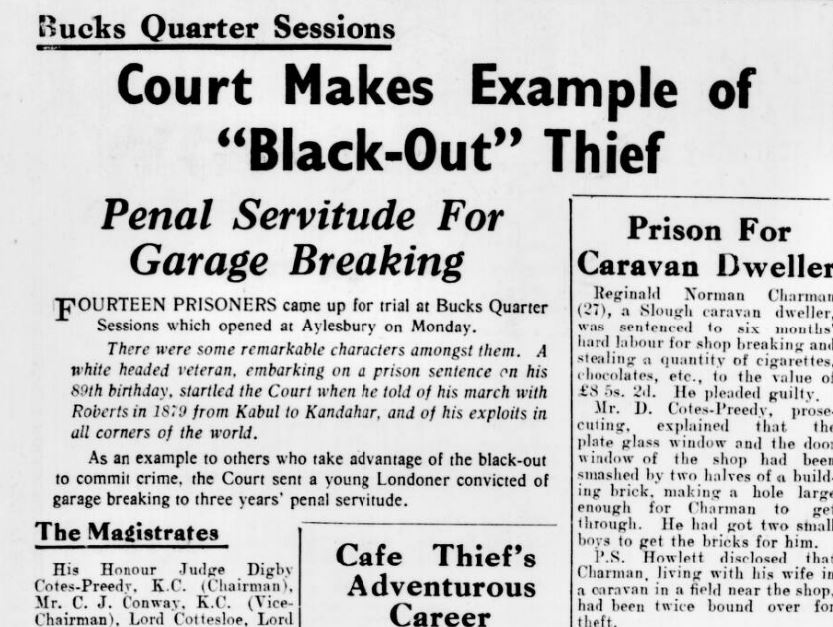

This kind of attitude towards blackout offenders was replicated elsewhere in the United Kingdom. At the Bucks Quarter Sessions, as reported by the Bucks Advertiser & Aylesbury News on 5 January 1940, Judge Cotes-Preedy told thief Robert Lawrence:

‘You committed this offence at a time when the country is under the difficulty of the black-out, when it is easier for people who are evil-minded to do these things. People carrying on business – difficult enough in these times – must be protected against men like you. We must make an example…’

During wartime, 29-year-old Lawrence, who was described by the newspaper as an ‘ex-convict’ from London, was seen as the lowest of the low. He was sentenced to three years’ penal servitude for breaking into a garage at Gerrards Cross during the blackout, and stealing 316 spark plugs, which were worth nearly £90.

‘Crime Black-Out’

But as 1939 came to an end, and the new year rolled around, newspapers began to publish some interesting statistics regarding crime in the United Kingdom. In a reversal of early expectations, the blackout had reportedly not actually led to an increase in criminal activity.

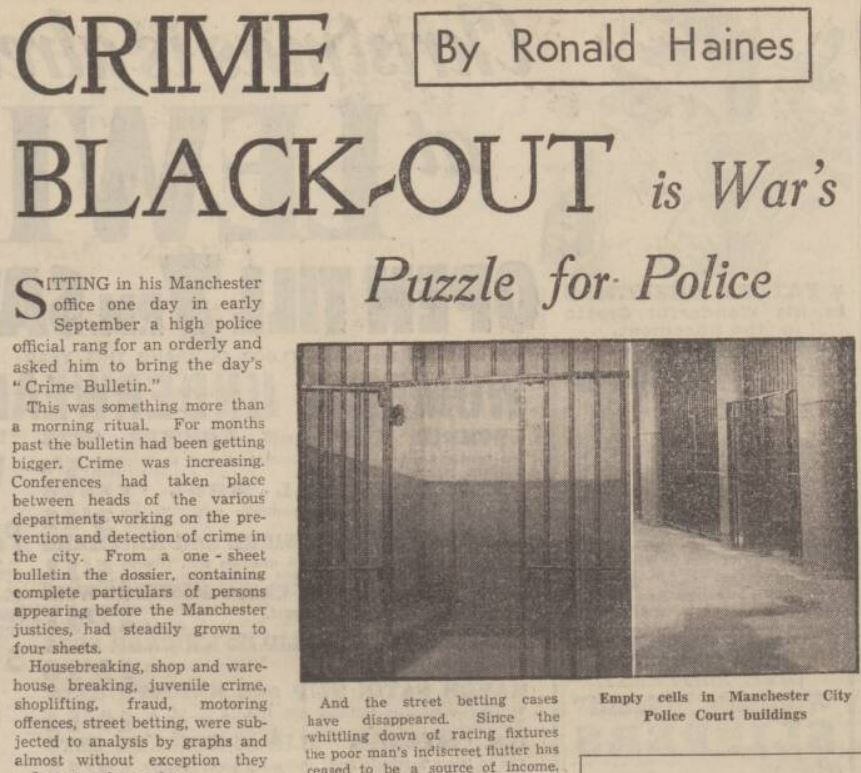

Ronald Haines, writing for the Manchester Evening News on 15 December 1939 on the ‘Crime Black-Out,’ noted how:

In some mysterious way which cannot be fully explained the outbreak of war effectively blacked-out the commission of crime in the city. Statistics compiled by court and police authorities show a steady decline in the number of cases heard in the lofty court rooms of the Minshull-street Police Court. The atmosphere is different. The old rush and flurry has given place to an ordered calm. The crowds in the big waiting room are smaller.

Haines describes how Manchester police themselves were ‘puzzled by the dearth in crime,’ believing that the blackout ‘would provide tempting opportunities’ for would-be criminals. Indeed, the only crime that was up in the city was ‘bicycle stealing.’

And this ‘crime blackout’ was mirrored in London, as H.V. Norton for the Daily Herald noted some months later in April 1940. According to the Metropolitan Police, crime had dropped 27% in the first month of the blackout, September 1939, when compared with September 1938. Meanwhile, during the first few months of 1940, there had been ‘approximately a 2 ½ percent decrease in crime compared with 1939.’

Norton talked to a ‘senior police officer’ with the Metropolitan Police to get his view on the decrease in crime, the officer relating how:

‘I am not easily surprised…but I must say that the fall in crime during the black-out has surprised me. It is probably due to the difficulties of transport, for the modern criminal is a car-driver, and to the harsh penalties imposed for black-out crime. While there has been a slump in general crime, there has been an increase in certain classes of crime, such as bag-snatching, thefts of bicycles, thefts from standing cars and telephone boxes.’

Petty theft seemed to be up, but generally speaking, the officer was of the opinion that ‘London has not become more wicked since the war and the black-out.’ He added:

‘…the black-out has kept away many who in ordinary times would be out looking for trouble. It all boils down to this. The professional criminal has not increased his activities because of the black-out, while many people who would ordinarily be out having a gay time stop safely at home.’

‘Black-Out Murder’

But serious crimes continued to be committed during wartime, with women in particular becoming victims of violent, random, crimes.

Indeed, a murder was committed in the early days of the blackout in Edinburgh, as the Newcastle Evening Chronicle reported on 15 September 1939, with the headline of ‘Murder in the Black-Out.’ The body of 52-year-old Isabella Ralph (also known as Isabella Pope or Isabella Donnelly) had been found under a tree in meadows near George Square. She had definitely been killed during the blackout, as police officers had seen her at nine o’clock outside a pub in Cowgate. It was noted that Isabella ‘appeared quite sober.’

Isabella was not the only woman to lose her life during the blackout. On 18 October 1940 the Belfast Telegraph reported on a ‘black-out murder in London.’ The 40-year-old manager of an off-license next to the Alexandra Park Tavern, Wood Green, had allegedly been ‘shot by masked gangster’ during an air-raid. The dead woman was Gwendoline Cox, who was said to have been ‘of a cheerful disposition.’ Gwendoline had apparently refused to hand over the money from the till, which led to her death, although the newspaper notes how ultimately ‘nothing was taken from the till.’

In March 1941 19-year-old Eileen Barrett, a cashier, church secretary, and ‘school sports champion,’ fell victim to the blackout and the random violence against women that came with it. The Newcastle Evening Chronicle on 26 March 1941 reported how Eileen had been travelling back home to Trawden, Lancashire, from night school, when she was attacked.

The newspaper chillingly relates how Eileen was ‘attacked from behind’ as she waited for her bus. As she screamed, a man ‘standing nearby’ rushed to her aid, but he was too late. Eileen, who had not felt like attending night school that evening, had been stabbed in the back, later dying in hospital.

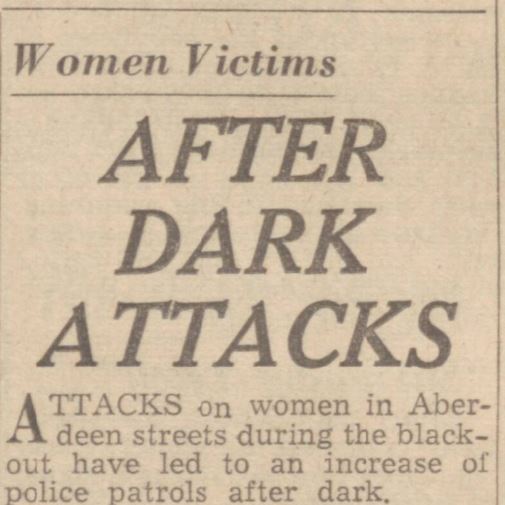

‘Women Victims – After Dark Attacks’

Danger lay in the dark streets as the war wore on. In January 1942 the Nottingham Evening Post reported on a new type of blackout crime in Nottingham – clothes slashing. The majority of victims were women, the Midlands newspaper relaying how:

The victims in the majority of cases are women, and on Sunday night it was a woman who had a new and expensive coat ruined with a deep slash, apparently made by a razor blade, down the back. The blade went through the coat and the clothing underneath.

Thankfully, in this instance, it was just the women’s clothes that were damaged, but the same was not be said for the women who suffered assaults during the blackout in Aberdeen over a year later. The Aberdeen Press and Journal on 28 September 1943 reported how ‘attacks on women in Aberdeen streets during the black-out have led to an increase of police patrols after dark.’

The most serious of these occurred on Wallfield Crescent, where a young woman was set upon on the doorstep to her home. Despite being ‘struck blows on the head with a brick,’ the woman survived and was taken to the Royal Infirmary, where she told police how she:

…became aware of being followed by a man in Esslemont Avenue while on her way home. The man overtook her, and then stopped at the junction of Belgrave Terrace and Esslemont Avenue. The woman continued on her way, and the attack was made at the door of the tenement house where her home is. When attacked she screamed, and her cries attracted the attention of a policeman. He went to her assistance.

Her life was most likely saved thanks to the intervention of the police officer, but elsewhere in Aberdeen these random attacks against women continued in the blackout. Women had been followed by men in the Ferryhill, Woodend and Rosemount districts, some having their handbags ‘snatched out of their hands.’ This crime spree was accompanied by the ‘theft of ladies’ underclothing’ from local shops.

The Blackout Ripper

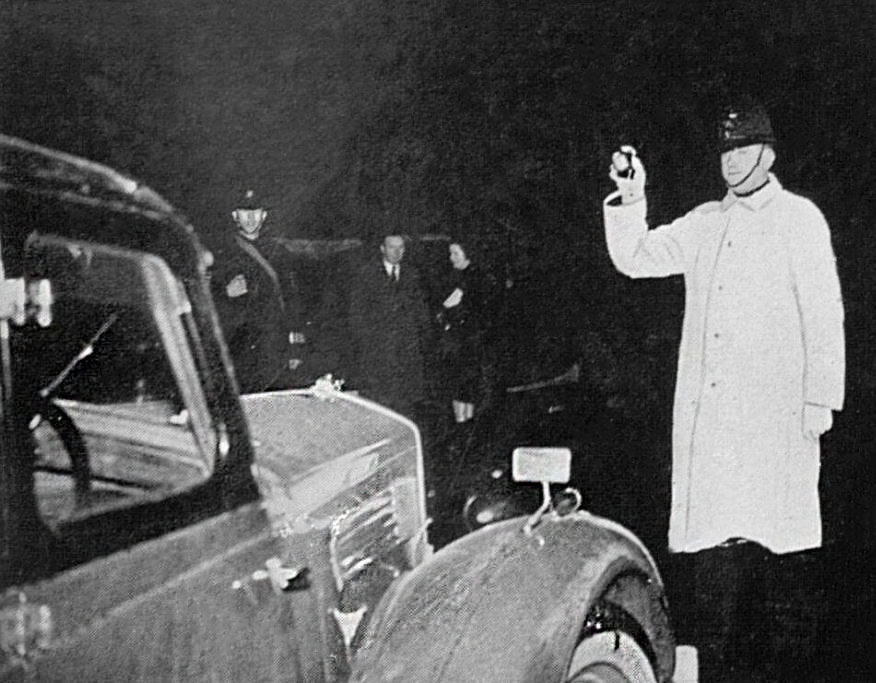

Perhaps one of the most infamous criminals to operate in the darkness of the blackouts was Gordon Frederick Cummins, a member of the Royal Air Force. Across a six day period in February 1942 he murdered four women in London’s West End, and attempted to murder two more. Due to it being wartime, and the sadistic mutilations he made to some of his victims’ bodies, he became known as the ‘Blackout Ripper.’

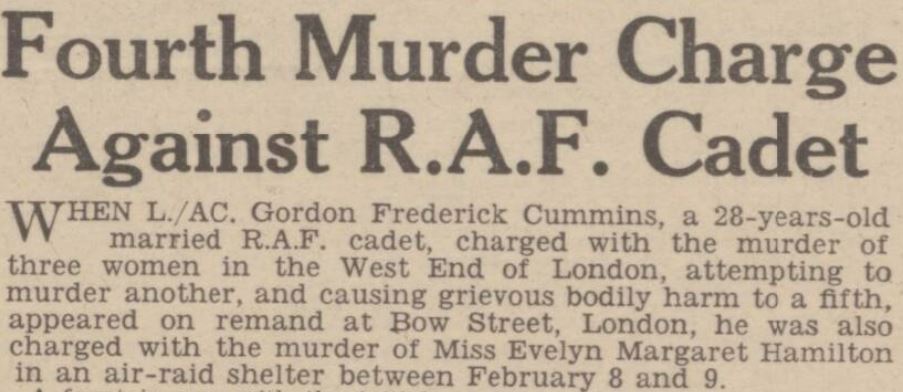

On 20 February 1942 the Leicester Evening Mail reported on the sensation that the arrest of Cummins had caused, as a ‘long queue’ waited outside Bow Street Police Court, where the accused murderer appeared on remand. At Bow Street Police Court he was charged with the murder of Mrs Evelyn Oatley (who was also known as Nita Ward, aged 30), who was found stabbed at her Soho flat on Wardour Street, Mrs Margaret Florence Lowe (aged 43), who was found strangled in her flat at Gosfield Street, and Mrs Doris Jouannet (aged 32), who was discovered strangled in her bed at her home in Sussex Gardens, Paddington. He was also remanded on the charge of causing grievous bodily harm to Mrs. Greta Heywood at her home at St. Alban’s Street, Haymarket.

The attack on Greta, also known as Margaret, would ultimately lead to Cummins’ discovery. Whilst strangling Greta, he was disturbed by a delivery boy. In his haste to get away, he left his RAF-issued gas mask and haversack, items that were traced back to him.

Over a month later on 26 March 1942 the Coventry Evening Telegraph reported how the 28-year-old Cummins had also been charged with the murder of Miss Evelyn Margaret Hamilton in an air-raid shelter in early February. The newspaper outlined how:

The fourth charge of murder accused Cummins of murdering Miss Hamilton, aged 40, in Montagu Place, Marylebone. Mr. Evans [prosecutor] said that Miss Hamilton was employed as a chemist’s assistant at Hornchurch, Essex, and left on February 8 to go to Grimsby. She was seen in a West End restaurant about midnight. The next day her body was found in an air raid shelter. A handbag she was known to have been carrying was missing.

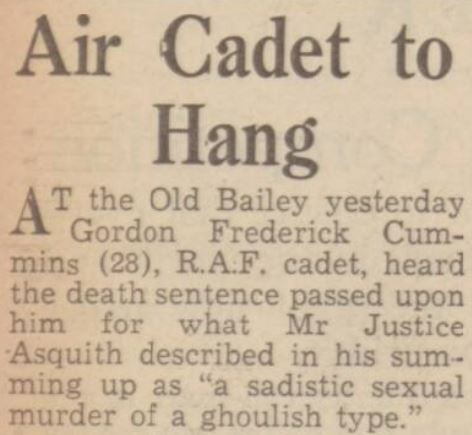

To the relief of the British public, Cummins was found guilty of the murder of Evelyn Oatley (English law at the time dictated that he could only be tried for one of the murders) in April 1942. The Aberdeen Press and Journal on 29 April 1942 reported how Cummins was sentenced to death by Mr Justice Asquith, who labelled his crime as ‘a sadistic sexual murder of the ghoulish type.’

In response, Cummins declared that he was ‘absolutely innocent,’ despite the jury finding him guilty after just thirty-five minutes. The other murders and attempted murders were not referred to during the trial.

Conclusion

So whilst the British press were quick to provoke fear about the blackout being a criminal’s paradise, and a few months later, were keen to dispel such rumours, the truth most likely lies somewhere in between. Crime, whatever the national situation, always occurs, and there were likely some who took advantages of the conditions of the blackout for their nefarious ends. And some, like Gordon Frederick Cummins, had particularly nefarious intent, and he was executed for his crimes on 25 June 1943 at Wandsworth Prison.

What stories of blackout crime and other dark deeds can you find in our Archive? Register with us, and start your research journey today.