Eighteenth century writer, philosopher and early feminist Mary Wollstonecraft faced censure in her lifetime, not just for her radical beliefs, but also for her rejection of societal norms. Long after her death, however, attitudes began to shift, as she gained recognition as a trailblazing fighter for women’s equality and became an inspirational figure in the women’s suffrage movement.

Following on from our blog on the life of Mary Wollstonecraft, in this second and final blog we shall examine the writer’s legacy. We shall look at how negative contemporary views gradually transformed into appreciation, not only for her works but for the way she boldly lived her life, outside of the status quo. Using newspapers from our Archive, we shall trace how she became a figurehead for the women’s suffrage movement, and how her memory was reclaimed as a trailblazing women’s rights pioneer.

Register now and explore the Archive

Mary Wollstonecraft the ‘Philosophical Wanton’

We know from our previous blog that the Scots Magazine in May 1798 published a damning near-contemporary look at Mary Wollstonecraft’s life, just a few months after her death at the age of just 38. In the article’s introduction she is dubbed a ‘philosophical wanton,’ but it is at the end of the piece that criticism of the recently deceased writer reaches a crescendo:

Such was the catastrophe of a female philosopher of the new order; such the events of her life; and such the apology for her conduct. It will be read with disgust by every female who has pretensions to delicacy; with detestation by every one attached to the interests of religion and morality; and with indignation by any one who might feel any regard for the unhappy woman, whose frailties have been buried in oblivion. Licentious as the times are, we trust it will obtain no imitators of the heroine in this country.

At the heart of this criticism of Mary Wollstonecraft is the affront that she dare have sex outside of marriage. It is not about her philosophical works, the argument that she put forward for female equality, it is about the philosophy of how she lived her life. A life that was cut short, the Scots Magazine suggests, because of her immorality. Mercifully, however, as the article suggests, at least her story, that of a fallen woman entering an early grave, could serve as a parable for those other women wishing to follow her example:

It may act, however, as a warning to those who fancy themselves at liberty to dispense with the laws of propriety and decency, and who suppose the possession of perverted talents will atone for deviations from rules long established for the well-government of society, and the happiness of mankind.

Such was the mountain of contempt that the legacy of Mary Wollstonecraft faced. Reparation seemed unlikely, but what followed in the decades to come was a slow reclamation of her life and legacy.

An ‘Historic Personage’

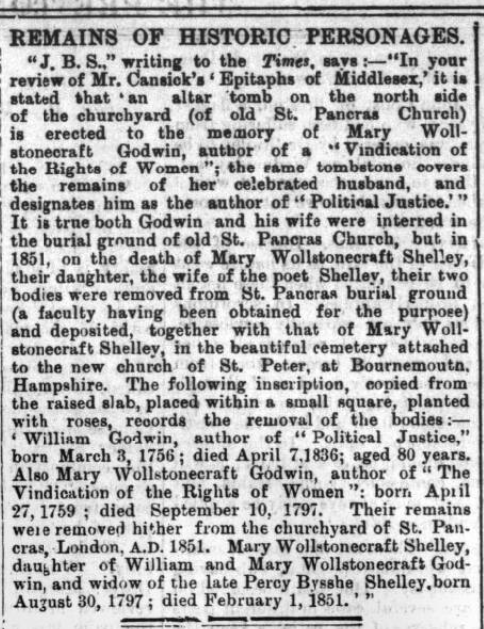

Reparation was indeed affected at a slow creep. A mention of Mary Wollstonecraft and her husband in April 1877 in the Preston Pilot managed to avoid any vitriol of the previous century. This piece dealt with the removal of Mary Wollstonecraft and her husband William Godwin from their resting places at the Old St Pancras churchyard to new tombs at St Peter’s, Bournemouth, to be buried alongside their daughter, Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley.

The bodies of Mary Wollstonecraft and William Godwin are described as the ‘remains of historic personages’. They are now archaeological curiosities, her the author of A Vindication of the Rights of Women, and him the ‘celebrated’ author of Political Justice. There is evidence, however, of a softening in attitudes towards the pair, for as the Common Cause relates in December 1920, ‘both Mary and William Godwin were widely and rather unusually unpopular during their lives.’ William Godwin is now ‘celebrated,’ whilst there is an absence of opinion in relation to his wife, her name tellingly does come first in this piece.

‘Another Messalina’ – A Century Later

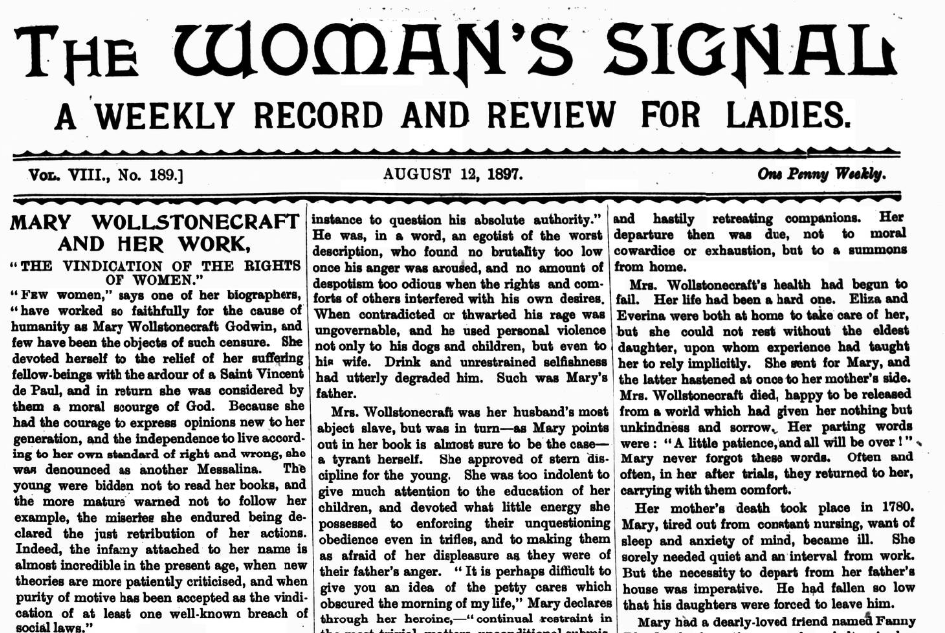

We find more mentions of Mary Wollstonecraft some twenty years later in the press, in the year 1897. This is no coincidence, for this year marked the centenary of her death.

Early women’s suffrage publication Woman’s Signal on 12 August 1897 published a piece entitled ‘Mary Wollstonecraft and Her Work.’ Not only did this piece provide a long and detailed look at Wollstonecraft’s life and writing, it also summed up the almost unsurmountable contempt towards her during her lifetime:

‘Few women,’ says one of her biographers, ‘have worked so faithfully for the cause of humanity as Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin, and few have been objects of such censure. She devoted herself to the relief of her suffering fellow-beings with the ardour of a Saint Vincent de Paul, and in return she was considered by them a moral scourge of God.’

The piece continued:

‘Because she had the courage to express opinions new to her generation, and the independence to live according to her own standard of right and wrong, she was denounced as another Messalina. The young were bidden not to read her books, and the more mature warned not to follow her example, the miseries she endured being declared as the just retribution of her actions.’

Now, a century later, this new Messalina (the original being the third wife of Roman emperor Claudius, known for both her power and promiscuity) was being extensively profiled not only in the pages of the Woman’s Signal, but by The Sketch, a light-hearted, pictured-filled, publication for the family. This piece, published on 29 September 1897 and penned by Arthur Hayden, declared how ‘although not perhaps a typical literary woman of the eighteenth century, [Mary Wollstonecraft] deserves to be remembered.’

‘An Early Claimant for Feminine Freedom’

Such a notion that Mary Wollstonecraft deserved to be remembered had, therefore, reached the popular press a century after her death. Other areas of the popular press, however, would need some convincing.

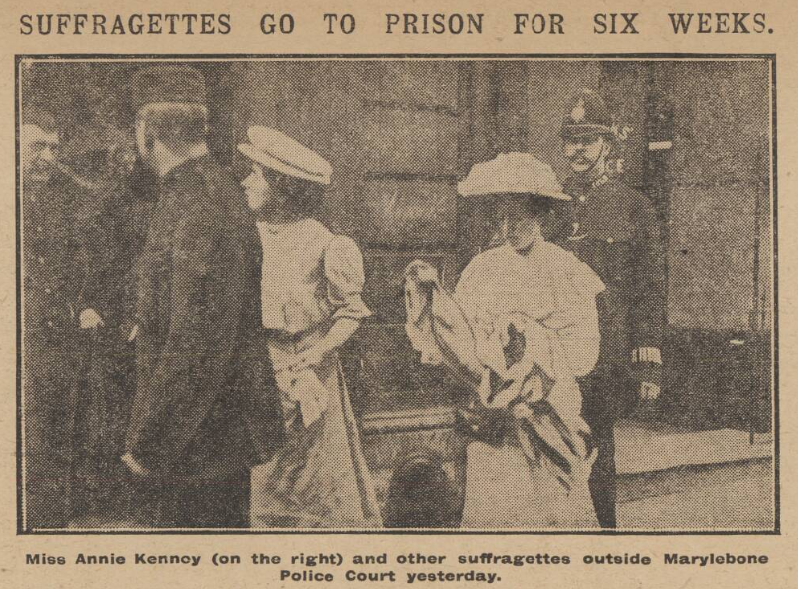

On 16 October 1906 influential London daily newspaper the Westminster Gazette published an article under the heading ‘An Early Claimant for Feminine Freedom.’ This piece was printed in response to the burgeoning women’s suffrage movement, or the ‘ebullience of the Suffragette,’ as the paper put it. Such open ‘revolt against male domination’ recalled ‘one of the early claimants for feminine freedom,’ Mary Wollstonecraft.

However, as the Westminster Gazette rather disparagingly remarked, Wollstonecraft’s ‘subsequent unfortunate career,’ that is, her becoming an unmarried mother, ‘did not help to win converts.’

‘One Who Helped Women to Hope’

And yet, Mary Wollstonecraft was being written about more and more, as the women’s suffrage movement in Britain continued to gain momentum. M.E. Ridler, writing for The Vote in September 1910, provided a profile of Mary Wollstonecraft’s life and work. Ridler enters into the conclusion of their piece by observing how:

Much has been accomplished since Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin was laid to rest in Old St. Pancras Churchyard. Girls nowadays come and go with the same freedom as their brothers, the mode of their education has been revolutionised, and they earn their living in ways which even thirty years ago would have occasioned speechless dismay.

Despite such advances, however, the legacy of Mary Wollstonecraft provided an important rallying call, as she was promoted to the figurehead of early feminism:

Much yet remains to be done, however, before the reforms so ardently desired and so heroically advocated by this apostle of sex equality are attained…The name of Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin will go down to posterity as that of one who helped women to hope, and, so doing, helped them to live.

‘The First Suffragette’

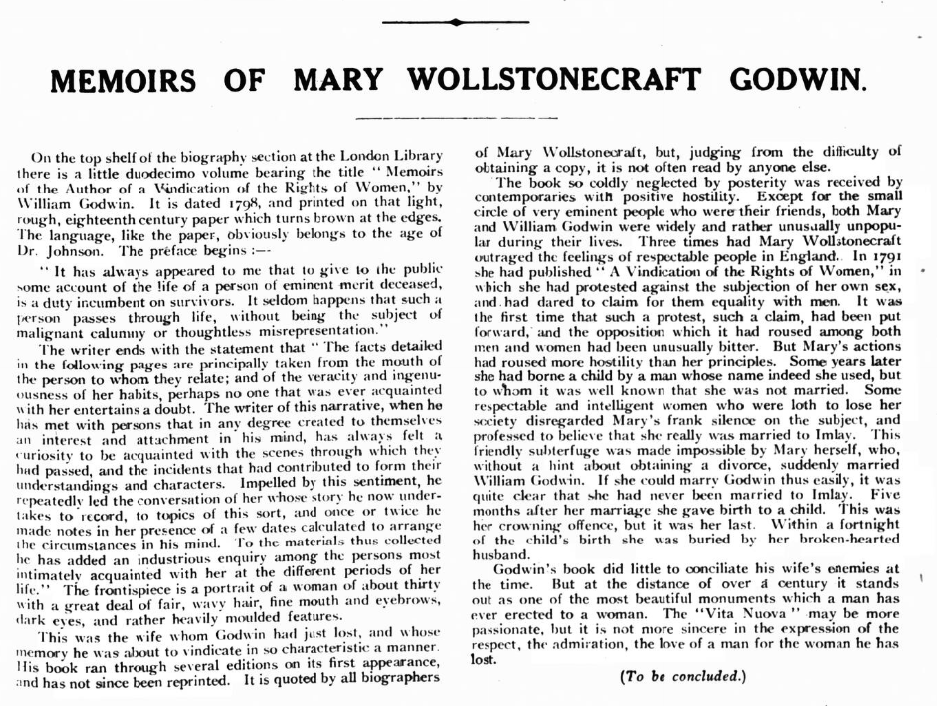

The reclamation of Mary Wollstonecraft and her reputation, her importance as a founder of feminist philosophy, had well and truly begun. In December 1920, after women had gained limited access to the vote in Britain, the Common Cause printed a moving reclamation of The Memoirs of Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin, published by Mary’s husband William Godwin after her death.

The piece for suffrage title the Common Cause explained how:

On the top shelf of a biography section at the London Library there is a little duodecimo volume bearing the title ‘Memoirs of the Author of a Vindication of the Rights of Women,’ by William Godwin. The book so coldly neglected by posterity was received by contemporaries with positive hostility.

The Common Cause notes how the book ‘did little to conciliate [Mary Wollstonecraft’s] enemies at the time,’ but movingly observes how ‘it stands as one of the most beautiful monuments which a man has ever erected to a woman.’

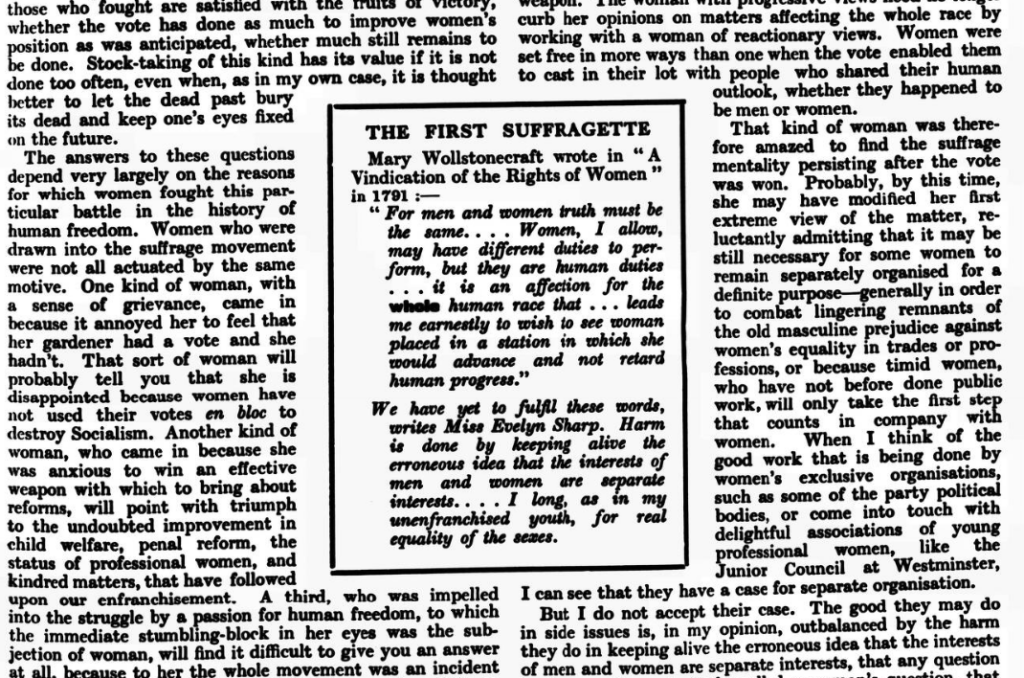

Meanwhile, over a decade later, and a few years after women had gained the vote on an equal footing to men, socialist publication Clarion printed a small inset piece entitled ‘The First Suffragette.’ This figure was Mary Wollstonecraft, and a line from her most famous work A Vindication of the Rights of Women is quoted. The passage expresses Wollstonecraft’s ‘earnest’ wish to ‘see women placed in a station in which she would advance and not retard human progress.’

Such a wish provokes suffragist, writer and pacifist Evelyn Sharpe (1869-1955) to observe how:

We have yet to fulfil these words… Harm is done by keeping alive the erroneous idea that the interests of men and women are separate…I long, as in my unenfranchised youth, for real equality of the sexes.

The vote may have been secured, but as Mary Wollstonecraft desired so many years before, there was still much to be done.

An Enduring Legacy and a Bicentenary

As the fight for women’s equality continued through the twentieth century, taking new forms, such as the Women’s Liberation Movement of the 1960s onwards, Mary Wollstonecraft’s legacy continued to educate and inspire.

For example, the Port Talbot Guardian on 29 February 1968 reported on a talk given by Mr. Gwyn Illtyd Lewis of the University College of Swansea on ‘the life and work of the 18th century pioneer of Women’s Rights, Mary Wollstonecraft.’ Delivered to the Social Studies Section of the Briton Ferry Townswomen’s Guild, Lewis explained how Wollstonecraft was ‘an inspiration to the reformers who were to follow in the votes for women campaign.’

Meanwhile, in May 1986 the town of Beverley ‘paid tribute‘ to Mary Wollstonecraft by unveiling a green plaque in her honour. As the Beverley Guardian described, Mary Wollstonecraft had lived in Beverley ‘as a girl’ during the 1770s. From dishonour to this new honour, attitudes towards the writer had come a long way.

By 1992 Mary Wollstonecraft was again being celebrated. This celebration marked the ‘bicentenary of the publication of A Vindication of the Rights of Women.’ Not only now were such anniversaries being remembered, as they were in the 1890s, they were being celebrated. The bicentenary was marked, as the Sunday Tribune describes, by the performance of A Dangerous Reputation in Dublin. Starring Fiona Shaw, Francesca Annis, Juliet Stevenson and Jacquetta May, the show combined ‘reading and songs.’

The world had certainly come a long way since the publication of A Vindication of the Rights of Women, and the vilification of a woman for simply daring to represent something other. Mary Wollstonecraft was a pioneer in every sense of the word, and deserves recognition and remembrance today as a trailblazing feminist figurehead.

Find out more about Mary Wollstonecraft and other inspirational women like her in the pages of our Archive today.